Archive for August, 2011

August 30th, 2011 by dave dorsey

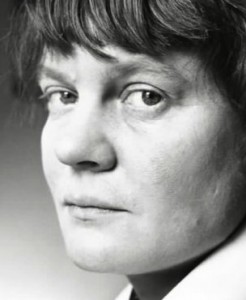

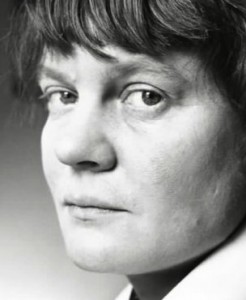

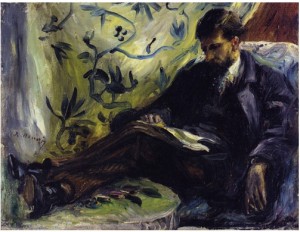

Iris Murdoch

I read a tremendous book a few months ago called Shop Class is Soul Craft, by Matthew Crawford, about the philosophical satisfactions of skilled physical labor. I heard about the book from my friend Walt—aka, Sancho—down in Tennessee, and I promptly ordered it and read it in a couple of sittings. It celebrates the dignity, beauty and intelligence of craftsmanship, and it makes me want to tear down my R1150R and put it back together again, just to get physical with my motorcycle in some way other than riding it. It’s a book people in Washington and on Wall Street ought to read, though they never will. They might realize that a country strong in the trades—a country good at building and repairing physical objects, a place where the average voter knows a socket wrench from an Allen wrench—is one that produces value the rest of the world actually needs. (How to revive manufacturing here in the U.S. is part of the economic enigma that needs to be deciphered for our economy to revive—and to wean ourselves from the financial sleight of hand that has been passing for economic growth the past couple decades.) It’s a sophisticated book by a man who left his position at a Washington think tank to repair motorcycles for a living. You can see some of his own craftsmanship at www.shockoemoto.com. Yet the real joy of the book for me was that it introduced me to yet another book, The Sovereignty of the Good, by Iris Murdoch, the British philosopher and novelist. When I finished Crawford’s book and started to read Murdoch’s, I realized I’d found yet another foundational piece of writing—like The Doors of Perception—that helped explain why painting matters, especially representational painting. (The writing about painting that means the most to me, for some reason, often gets done by people outside the field of art—in this case by a motorcycle mechanic.)

You can open Murdoch’s book almost anywhere and come away with a sentence that makes you say, “Of course! I knew that.” And then you ask yourself, “Didn’t I?” Nicholson Baker used to do that for me on every page, some little observation about the engineering of a plastic straw, vs. paper, that would make you pay attention to your own subliminal awareness of how daily objects work, how they’re designed, perceptions that underlie your experience of life without your being quite conscious of them, until you’d read The Mezzanine. Murdoch does this on a more abstract plane. For example, everyone knows how discomfiting it can be to watch a John Cassavetes film or one by the young Mike Leigh, or to glance at certain great paintings for the first time, one of Lucien Freud’s nudes, for example. Murdoch has a simple perspective on this:

(good art) resists the easy patterns of fantasy . . . the recognizable and familiar rat-runs of selfish day-dream. Good art shows us how difficult it is to be objective by showing us how differently the world looks to an objective vision.

Crawford elaborates wonderfully on this in his own book: More

August 30th, 2011 by dave dorsey

The award-winning book

Slightly belated kudos to Manifest, a unique gallery and publisher in Cincinnati, for winning the Silver Medal in the fine arts category—the highest ranked category among all the awards they bestow—at the Independent Publisher Book Awards in New York City recently. This maverick, non-profit organization—supported by individual donors, ArtsWave, and The Ohio Arts Council—has been doing an amazing job of helping serious emerging artists from around the world show their work by holding juried shows and publishing a full-color catalog of every work it exhibits. Every event at Manifest gets its own catalog, and these books are perpetually kept in stock for purchase by anyone who wishes to see excellent new work being done, around the world. Manifest won this award for one of the most recent in a series of annual books it publishes—the 5th International Drawing Annual, showcasing 114 works by 72 artists from Australia, Canada, Croatia, England, France, Germany, Japan, Portugal, Scotland and the United States. The work included in the book was selected from nearly 4,000 entries.

Manifest represents a small but influential island of sanity and balance—not hewing to any particular academic creed and not swayed by whatever happens to be selling at any given time. Work is chosen on merit by eleven jurors—professional and academics qualified in the field of art, design, criticism, and art history. All final selections are curated by Jason Franz who, in an email to me once summed up the stature and neutrality Manifest represents with the perfect quip: “We are the Switzerland of the art world.” For those of us seeking little more than a Swiss work visa into the world of art—rarely dreaming of full citizenship—it’s a happy moment to hear this place getting the recognition it deserves, as both a gallery and a publisher. In its press statement, Manifest put it perfectly: “The award is tangible proof that Manifest is fulfilling its mission to reach out to a global audience from our small headquarters in East Walnut Hills in Cincinnati, to stand for something that artists appreciate and the public respects, and to honor the creative work of so many separate people all connected by their participation in our projects.”

August 26th, 2011 by dave dorsey

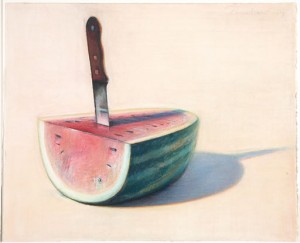

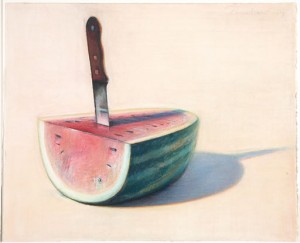

Watermelon with Knife

My wife and I meet our son and daughter in Palm Springs for vacation every year in August, when it’s super-cheap and affordable, and, well, broiling hot. Don’t challenge me on this. We love it. It’s a dry heat, as Bill Paxton said in Aliens. We were there again last week—golf, golf, golf, cicadas, scurrying quail, hummingbirds sometimes thick as insects on the front nine, doves, mockingbirds, roadrunners, moonlit mountains, Corona in bottles, gin and tonic, swimming, running in 95 degree heat, cards, epic dinner conversations, and drives to the Palm Desert Apple Store for a new trackpad. On top of all that, I finally visited the Palm Springs Art Museum. I went to see what I thought was a late Manet in their permanent collection, since I’d seen it in a promotion on our visit a year earlier, and it was there, all right—a gem, larger than I thought, all vigorous brushwork, the fearless shorthand execution of a master who knew he would soon die. I discovered, though, that it was part of an anonymous private collection on loan every summer, when the owner flew to cooler climes. Nice trade of services: you guard my paintings from thieves, heat and humidity, and I’ll let you show them to the public, but only if you don’t let anyone take pictures. Doh! It was a dazzling assembly of work, and I tried like hell to pilfer a few images with my iPhone, but the guards were sharp and vigilant. (My son-in-law, John, actually acted as my wingman and wandered off to see if the guard wouldn’t follow him, giving me the privacy to steal a few shots, but no dice. Though I was disappointed that he kept an eye on me, the guard was obliging enough to tell me the paintings in this exhibition were all owned by one local collector, who wanted anonymity, no doubt to protect his paintings.) In total, the room reminded me of a much smaller version of the Duncan Phillips Collection in Washington. It was a selection that showed the collector’s unerring ability to spot tremendous Modernist work: Van Gogh, an early Matisse, a whole series of Picasso drawings, three Joan Mitchells, a Rothko, a little Renoir portrait sketch more intriguing than most of the standard Renoir  fare I’ve seen over the years, a tremendous, placid non-figurative De Kooning, the Manet, and what turned out to be a small revelation for me: a set of a half-dozen Thiebauds. They were all a lesson in how to paint irresistible images, yet one of them was astonishing.

fare I’ve seen over the years, a tremendous, placid non-figurative De Kooning, the Manet, and what turned out to be a small revelation for me: a set of a half-dozen Thiebauds. They were all a lesson in how to paint irresistible images, yet one of them was astonishing.

It occurs to me that I’ve been giving Thiebaud a lot of big ups, almost despite myself, because as much as I admire him, and love the late-career landscapes, there isn’t any single image of his that has knocked me out me the way this painting did. It’s an oil on panel of a wedge of watermelon impaled by a large cutting knife. I found another version of the subject online—not the same painting—and it’s not nearly as good. The photograph doesn’t even come close to conveying the saturation of his color in the Palm Springs painting, the depth of thickly applied oil that seemed to soak up the light and give you a rich tone from under the pa int’s surface, somehow. The knife had the shine of reflected light, and yet, at the same time, also had the flat abstract quality of Thiebaud’s typical work. The wooden handle was a marvel, and overall, the knife itself had an almost Arthurian sword-in-the-stone aura. The watermelon’s red fruit seemed polished and honed at the edge, with a neat semi-circle of seeds sown regularly just inside the rind, a couple strays having fallen to the surface below. And the shadow’s deep blue depths seemed to pull against the electric green of the fruit’s surface. The image he created resonated with all the pleasure of the man’s good cheer—as a viewer, you taste his subjects more than you simply see them—yet there’s an uncharacteristic implication of violence and even sex in this one. The color, the shine of the knife blade, the imagery of stabbing, the physical heaviness of what he shows you—the blade looks anchored firmly enough to quiver if you plucked it—it commands your attention with unusual authority, and yet all of these implications are bathed in his brilliant light and deeply saturated color, so that the effervescent quality of Thiebaud’s vision only seemed intensified by this mortal-seeming wound, inflicted for the sake of a summer dessert. Enjoy the sugar of those thirst-quenching bites, he seemed to be saying, and enjoy them all the more because that ominous knife casts a little strip of purple shadow down the center of the fruit. This unusual touch of duende, ultimately, seemed an almost ironic, serene reflection on a fate Thiebaud seems to have deferred indefinitely, now that he’s in his 90s.

int’s surface, somehow. The knife had the shine of reflected light, and yet, at the same time, also had the flat abstract quality of Thiebaud’s typical work. The wooden handle was a marvel, and overall, the knife itself had an almost Arthurian sword-in-the-stone aura. The watermelon’s red fruit seemed polished and honed at the edge, with a neat semi-circle of seeds sown regularly just inside the rind, a couple strays having fallen to the surface below. And the shadow’s deep blue depths seemed to pull against the electric green of the fruit’s surface. The image he created resonated with all the pleasure of the man’s good cheer—as a viewer, you taste his subjects more than you simply see them—yet there’s an uncharacteristic implication of violence and even sex in this one. The color, the shine of the knife blade, the imagery of stabbing, the physical heaviness of what he shows you—the blade looks anchored firmly enough to quiver if you plucked it—it commands your attention with unusual authority, and yet all of these implications are bathed in his brilliant light and deeply saturated color, so that the effervescent quality of Thiebaud’s vision only seemed intensified by this mortal-seeming wound, inflicted for the sake of a summer dessert. Enjoy the sugar of those thirst-quenching bites, he seemed to be saying, and enjoy them all the more because that ominous knife casts a little strip of purple shadow down the center of the fruit. This unusual touch of duende, ultimately, seemed an almost ironic, serene reflection on a fate Thiebaud seems to have deferred indefinitely, now that he’s in his 90s.

August 26th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Two Trucks, with Tools

Anyone who doubts that painting is mostly a physical engagement with the world should have followed me around the past three days. I drove to Chelsea, to help another painter, Rush Witacre, build a set of storage shelves at Viridian Artists on 28th St. As a member there, I donate 40 hours of labor every year—doing whatever needs doing when I can get into the city for it. When I joined Viridian, our director, Vernita N’Cognita, asked me, “Are you handy?” I should have known better than to be honest about it. Three days ago, just before I left, I stood in our kitchen and took that photograph (up above) of my cargo for the visit to Manhattan. A power drill, extra batteries, a stud finder, a level, tape measure and—oh yes—a painting for “Moved,” the show opening next month to celebrate our new space, a few blocks north of where the gallery had been located for a decade. It was a move I’d helped the gallery make in July by loading heavy objects into Rush’s four-door pickup truck and then lugging them up to the new space, in a building wedged between a Porsche/Bentley/Rolls Royce dealership on one side and, on the other, Scores, the strip club Howard Stern helped put on the map. Directly next door to our building was what appeared to be an apartment complex called Art +, with a motto painted onto the street-level window: “Chelsea, the birthplace of creative modern art and the home of bad behavior.” I’ve been a member-level supporter of both of those causes, at one time or another, so I feel at home when I’m here.

It takes about five hours to drive to Manhattan from our Rochester suburb, which almost seems like a commute to me now, I’ve done it so many times. Yet our first afternoon of work was a lesson in the relative meaning of mileage. More

August 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

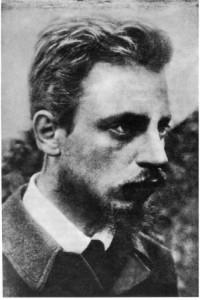

And yet the central issue for us is probably the question of whether the mystery at the heart of poetry (and of art in general) can be kept safe against the assaults of an omnipresent talkative and soulless journalism and an equally omnipresent popular science—or pseudo-science. It also has a lot to do with the weighing of the advantages and vices of mass culture, with the influence of mass media, and with a difficult search for genuine expression inside the commercial framework that has replaced older, less vulgar traditions and institutions in our societies. In this respect, it’s true, poets have less to fear than their friends the painters, especially the successful ones, who, because of the absurd prices their works can now command, will never see their canvases in the houses of their fellow artists, in the apartments of people like themselves, only in vaults belonging to oil or television moguls who don’t even have time to look at them. Still, the stakes of the debate and its seriousness are not very different and not less important than a hundred years ago.

—Adam Zagajewski, on Rainer Maria Rilke’s poetry, from Paideia

August 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

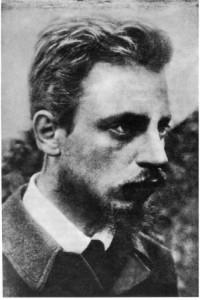

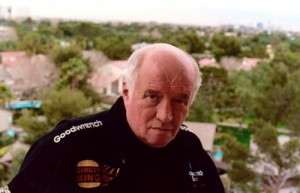

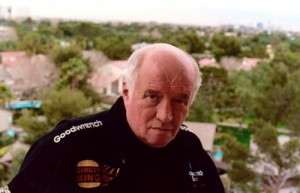

Dave Hickey

You cling to your favorite songs and books and paintings the way you once clung to your mother’s hand—because they help you become who you are and make you feel at home. Sometimes, when you see the beauty of a created thing, you recognize yourself in it and want to join ranks with anyone else who loves it the way you do. Last summer, I embarked on a 16-hour journey from Rochester through JFK and LAX to New Mexico—in retrospect, I might have been more comfortable going by wagon train—in order to join ranks, if only for an hour or two, with someone whose books have made me feel a little more at home in the world. Dave Hickey, one of America’s smartest art theorists, was scheduled to have a conversation with his friend, Ed Ruscha, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Tamarind Institute, and I showed up to listen.

Dressed all in black, with a venti-sized Starbucks coffee in hand, he was more physically imposing than I’d expected, bringing to mind Orson Welles or Harold Bloom, not only in the impression he made just sitting there, but also in the sense of his pre-eminence in his field. Balding, with a tonsured ring of dangling hair around the back of his head, he spoke in a quiet voice full of Texas, sounding like Slim Pickens trying not to be heard in the next room. While he and Ruscha traded jokes and memories, and speculated about art, I could hear behind Hickey’s comments echoes of his thinking in The Invisible Dragon, where he deconstructs the history of Western art in order to argue that beauty isn’t meretricious ornament but art’s lingua franca.

Art, he claims, is essential to the way we find order and belonging in the diversity and chaos of an open society. You buy a good drawing or lithograph and let it reorder a certain space in your house and your mind in exactly the way you vote for political leaders and give them permission to set boundaries for your life. More

August 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Thiebaud's world

I was watching a documentary not too long ago about a little pre-schooler, Marla Olmstead, who ostensibly paints beautifully composed abstracts. They are vivid, mostly cheerful celebrations of paint, and some of them are actually impressive. Unquestionably, though, they look as if someone much older had finished them. Dutifully, the documentary raises the question of whether her father has helped her paint them, or maybe is simply painting them himself—in my view they would be fine works of art even if Mr. Olmstead had been able to paint them only by pretending to be his little daughter. Now that would have been a more interesting, and certainly much funnier, investigation. But what struck me was how the director of My Kid Could Paint framed the story of Marla’s sudden emergence on the scene: as the triumph of innocent, playful joy in a jaded, postmodern art world with deadly serious pretensions of speaking truth to power, celebrating the abnormal, casting a cold eye on consumer culture, trying strenuously to be obscure and difficult, and in general doing what the French applaud as epater le bourgoisie—more or less giving the finger to the middle class, the average guy, the uninitiated. The art of cruelty, as it were.

I’ve always distrusted any view of art that assumes you need to know the secret handshake in order to really appreciate what’s going on. Matthew Barney is a genius of some kind, no question. His films are powerful and hypnotic. But I don’t have a clue what he’s doing, and I’m guessing most people who wandered with me through his Guggenheim show felt the same way. The movie about little Marla got me thinking about Matisse and his desire to paint pictures that would sooth the viewer, like an easy chair at the end of the day. Who would claim to have that goal, as an artist, now? But isn’t the art we love the art that matters most? Wasn’t that what Van Gogh and the Impressionists and the post-Impressionists were doing: painting images they believed viewers would love? Chagall, Klee, Janet Fish, Fairfield Porter, and many other painters were playing in that same space, not trying to shock anyone with their work, but to get people to look eagerly at the world, or at least at their paintings of it, with some measure of joy. And, in the process, maybe open a few minds, soften a few spirits, here and there.

Wayne Thiebaud comes to mind, doesn’t he? His landscapes construct an imaginative world with its own set of rules and laws: an alternate universe, a heightened version of the view you get from the window of a jet rising into the sky. They are visionary masterpieces, a kind of wish fulfillment, the work of a man painting exactly what he most wants to see. More

August 7th, 2011 by dave dorsey

Woodward's dream

Matt Woodward, an emerging Chicago artist, does graphite-on-paper drawings that thrive in the rich Middle Way between abstraction and representation, past and present, large and small, classicism and expressionism—pick almost any pairing of opposites and Woodward merges them with great originality. His method, so far, is obsessively invariant: he wanders a city, captures an overlooked architectural detail from an earlier decade–well, century–back when ornament and pattern were considered essential to our living space. He hunts for a finial, a fleur de lis, some overlooked niche of architecture—and then he creates a meticulous representation of these shapes through techniques that imbue the image with an evocative ambiguity. He sands and punishes huge sheets of paper, creating a surface full of unpredictable characteristics—which he sometimes assembles, like a puzzle, as Burchfield used to do—into panels large enough to use, in a pinch, as drywall for a large bedroom. Then he coats them with graphite dust, and finally, he draws by erasing the shapes he wants to show. It’s a brilliant inversion that goes to the heart of how time itself works: erasing what it is you want to see. What he achieves can evoke a slightly Faulknerian longing for ancient values, a world of allegiance to something more chivalrous than our media-drugged days, and yet the work has an immediacy, precision and freshness that feels entirely new. The vitality of his drawings derive from this paradoxical tension between extremes. The details are assiduously evoked, to the point where they actually shine, and yet you can’t quite pin down what it is you’re seeing—and so your mind shuttles desperately from one tentative sense of closure to another, not quite settling on a secure way to make sense of what he’s showing. He makes you dream, involuntarily, as part of this struggle to recognize what it is you’re on the way to seeing.

When I saw one of his wall-size triptychs two years ago in Rochester, NY, the effect was what Gaston Bachelard celebrated as the “oneiric” effect of certain spaces, which he equated with the half-conscious reverie induced by poetry. What had been a small cluster of grapes carved into the stone of an historic structure, though the alchemy of Woodward’s techniques, seemed to become a dreamscape, a circle out of Dante or a scene from Edgar Rice Burroughs. It was as much a vision of a physical world as an objective correlative for indeterminate psychological and emotional states. Woodward told me recently that he’d finished the work during a time of mourning over the death of his father—and his abiding preoccupation with the passage of time, had become, with his father’s death, agonizingly central to his emotional life. Art itself began as a desperate bid to hang onto something one loves, to steal it from time and save it through concentrated attention and representation, and Woodward work taps these motives. His work’s beauty is inseparable from a melody of grief that makes it come alive.