Archive for October, 2012

October 29th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Browsers at Manifest last Friday

I drove to Cincinnati last week to attend the book party at Manifest celebrating the two annuals they’ve just published—INPHA 1 and INPA 2. The books are an overview of examples of what Manifest considers best in current contemporary photography and painting. These are beautiful books, packed with incredibly accurate reproductions of work from around the world—for INPA 2, out of 1310 entries from 452 artists, Manifest’s jury chose 118 works by 72 artists. As the organization says of the painting annual on its website:

As a carefully designed book, the INPA enables Manifest to assemble a diverse array of works from around the world, without the limitation of physical availability, gallery space, or shipping logistics. Manifest’s book projects support our inquiry into the creative efforts of artists working today and serve to document the exceptional results for posterity, distributing artists’ efforts outside our gallery’s geographic radius.

I’ve been thumbing through my copies every day since I got home, and I’m still finding surprises and incentives to get back to the easel. It was a slightly absurd distance to drive for a two-hour event, about 825 miles there and back, but I stayed the night at Rush Whitacre’s studio in Beverly to divide the distance, and that turned out to be half the fun. I pressed apple cider with Rush and his friend Butch on Thursday night, until midnight, and then drove to Cincinnati with him the next day. We got together right after the event at Suzie Wong’s for a late dinner with Jennifer and Randy Wenker, and laughed MORE

October 24th, 2012 by dave dorsey

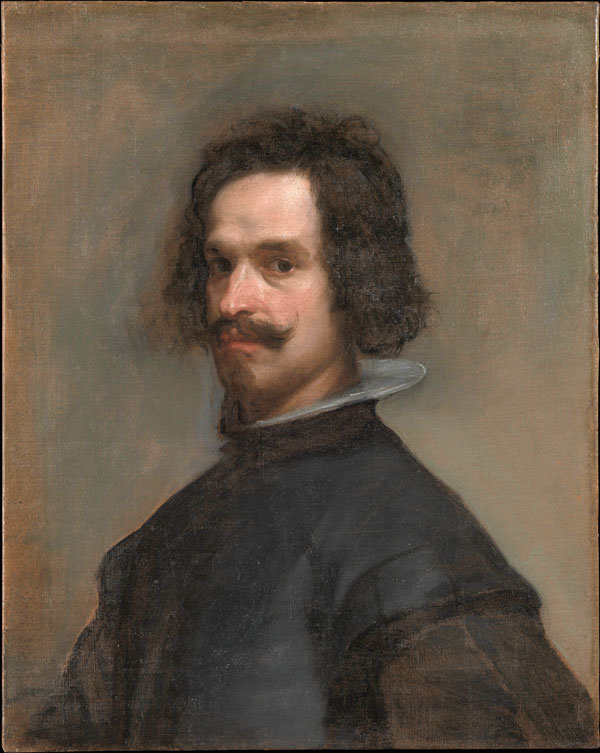

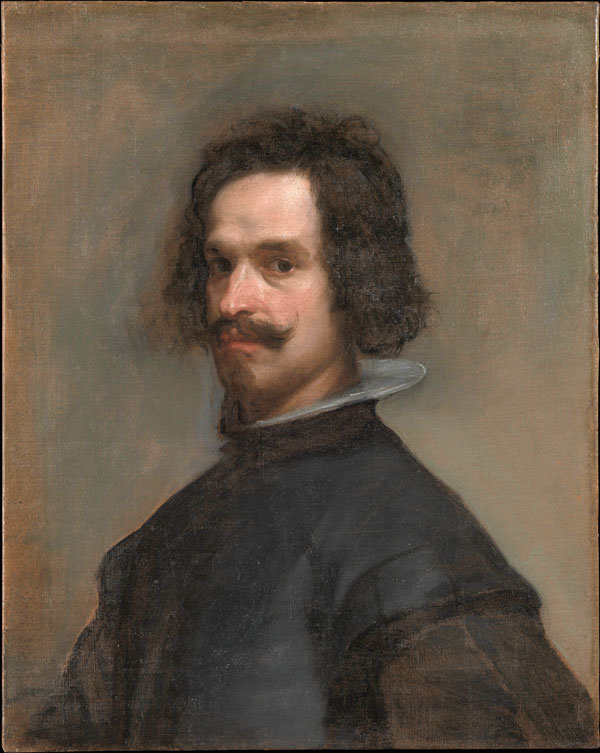

Study, Velasquez

Last year, I was hanging around Viridian Artists, up to no good, and Simon Cerigo came in to visit, and we talked about a show at Zwirner which I’d just seen a few hours earlier. I was still raving about it. “Too finished,” he said, of Michael Borremans, which at the time I thought was funny, since the technique I’d seen was anything but finished. It was economical, supremely confident. Masterful. (I haven’t checked lately. Is it OK to say master, if you don’t say “old” first?) This painting reminds me of that work, in retrospect. The body is just sketched in. The wiry hair is preternaturally rendered without a lot of arduous specificity. Try doing that sometime, that hair. Maybe it’s just the way the canvas is lit. I wish. And it’s just a study for The Surrender of Breda. Thin under-layers of paint with hardly a second or third application. You mistake the weave of the canvas for the weave of the sleeve, the paint is so insubstantial. I think maybe I’ll try doing nothing but studies. Oh, yeah, this is how it looks after the incredibly successful restoration a few years ago. (Somebody, please forward this to Cecilia Gimenez.) Anyway, Simon, I understood what you meant. Exhibit A, see above. But you’d still probably say, “too finished.”

October 21st, 2012 by dave dorsey

Jeffrey Deitch

The New York Times this morning published a great, balanced overview of the farcical tempest that’s been brewing over the tenure of Jeffrey Deitch at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. A couple months ago, a friend urged me to write about it, but I demurred, expecting someone more informed to do a much better job. Of course, as usual, that someone was the New York Times. As its story lays it out, the financially ailing museum had recruited Deitch to come in and turn things around, which he proceeded to do, by organizing shows and events, working outside the usual curatorial channels, bringing more people and more revenue through the doors, but alienating many supporters with big names. It would appear that Deitch believed getting people into the museum was more important than providing substance over style—for example, by hosting a show about Hollywood curated by Hollywood, meaning a James Dean exhibit curated by artist/actor James Franco, for example. However, he was doing his job. In short order, Deitch increased public awareness of the museum and lured people into the building. Once inside, the public was free to wander around and check out more substantial work. It’s a museum after all. That’s what these places do: offer anyone willing to pay admission a glimpse of ostensibly great art, if you’re willing to find your way to it. (Bread crumbs might work at the Metropolitan, which is always a challenge, though I’ve never tried it.) Long story short, Deitch infuriated a core group of highly-regarded artists and curators who “constitute a crucial faction here,” as the Times put it. Things reached a boiling point with one particular show: MORE

October 20th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Deciduous Dragon’s Offering, Kat King

Not too long ago, Kat King thought her artwork was actually coming alive. One of the dragon models that she’d assembled from leaves and husks and flower stems seemed to be moving on its own. When she got closer, she realized small insects had hatched and were emerging from the pods and husks she’d found in wooded tracts not far from her home in Chicago. She fetched a pair of tweezers and pulled the burrowing bug out of her dragon and was astonished to realize this was an exotic insect she’d just happened to read about: the death watch beetle. A little fumigation solved her problem, but the resonant mystery of the event wouldn’t die.

What made this episode so bizarre was that a short while earlier she’d gotten the word paradox stuck in her head and couldn’t get it out. So she looked up its definition, and it led her to a Wikipedia entry on paradoxical or cryptic animals.

As she tells it: “I found centaurs, griffins and serpents, snakes, and then dragons and then, after that, there was something called a death watch beetle. So, not long afterward, I . . . noticed little brown bugs were emerging from my assembled dragon.”

“Let me get this right. You had these insects living in the models,” I said.

“Especially the dragons. The pods must have had these things in MORE

October 19th, 2012 by dave dorsey

White Picket Fence, watercolor with charcoal and chalk on joined paper, Charles Burchfield

Also from the current Harper’s magazine, a glimpse of an exhibition at Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. In my view, more than almost any painting he did, other than one particular landscape in the phenomenal Whitney retrospective, (Heat Lightning,) this work fulfills Burchfield’s lifelong yearning to be a classic Chinese scroll painter It’s a bug he picked up while working as a guard at an Ohio museum. Every time I go back to his work, it looks more vital and original and somehow accurate. It shows you what’s actually there, not just what’s there to be seen. Those intense green marks of refracted sunlight at the top of the tree, echoing the little green notes at the bottom: you can almost hear this painting and feel the Indian Summer heat. I always imagine Burchfield, toward the end of his career, saying, “Oh, to have lived a thousand years ago in China.” I say, “Oh to be Charles Burchfield.”

October 19th, 2012 by dave dorsey

These boots were made for paintin’ . . .

Landscape artist Jim Mott has taken it upon himself to redefine the nature of art, travel, money, and hospitality in an age increasingly defined by individual insularity. – Christian Science Monitor

There is gift-exchange in my life, to be sure, but even I have never had the nerve to try an experiment as full as the one you undertook. Bravo! – Lewis Hyde, author of The Gift

You are perfectly right about landscapes being OK in the post-historical phase of art. But somehow more in the spirit of the times is your project of itinerancy, which has a performance dimension.

–Arthur Danto, philosopher and art critic

All that about my buddy Jim. Those esteemed voices were praising him for doing what he’s about to do, yet again. Wander around the country, looking for places where people will give him room and board for a night or two, in exchange for a painting of his host’s surroundings. It’s an exchange of gifts, both ways, and, to be honest, it seems Jim’s getting the short end of the stick every time, considering the quality of his work, but hey, if I could get Danto and Hyde to speak that highly of me, by giving my work away, I’d be on that in a second.

Mr. Mott sent me this email today, which I pass along with great enthusiasm. Somewhat in the spirit of his upcoming project, I may tie him to a chair and force him to stay the night here before he goes and liberate him only if he paints me a picture. He’ll do it willingly for almost anyone else who gives him a room and a little food. More on this after we get together to talk about it next week. Check out who interviewed him at the link below, Buffalo’s Righteous Babe herself.

American Road Artist (a.k.a. The Itinerant Artist Project)

ANNOUNCING THE GREAT LAKES ART TOUR

Fall 2012 and Spring 2013

“Art for hospitality across the US and Canada”

HOSTS WANTED: Open call for HOSTS in Great Lakes cities and all points in between

MORE

October 17th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Duncan Wylie, Twin Towers, Oil on canvas

I wish I had the time and discretionary income to fly to Paris to see the new Duncan Wylie show at galirie dukan hourdequin. Instead, I’ll have to settle for the slide show at the gallery’s website. It may be a far cry from standing before the paintings, but the website offers a way to magnify the surface of the paintings by hovering your mouse over them and that goes a long way toward demonstrating how well Wylie paints. (Thanks to Harper’s for including one of these paintings in its current issue, which is how I found it. Over the years I’ve consistently discovered more interesting art from Harper’s than from nearly any publication actually devoted to the subject of art.) The new work is a tour de force of pure painting, technically gorgeous and masterful, framed by the semi-ironic context of its content, a series of apocalyptic images of disaster and collapse. It’s Franz Kline meets 9/11. Wylie appears to be working from photography of natural and human disasters, with images that hint at a tenacious struggle to survive in the aftermath. The brushwork is incredibly bold and confident, and his handling of value and hue accentuate the AbEx look of spontaneity while also, paradoxically, increasing the sense of depth and three-dimensionality in these scenes of ruin. Often using blues and grays, or other combinations, to hint at duotone photography, Wylie fades the backgrounds into a narrow middle range of values, achieving a sense of haze, distance, as well as hinting at the tension between immediate disorder and memories of whatever violence created it. In some cases, he appears to paint the background and then, on the dry surface, conjures a demolished structure with a transparent layer, so that the forms and lines bleed through the walls of the building in the foreground, giving it an eerie flesh-like translucency. Wylie’s sense of color is incredibly subtle and effective. His brushwork merges subject and style—the energy and seeming abandon of his paint application, as he unifies his image–and it both mirrors and works as a counterpoint to the explosive events that appear to have taken the world apart. His titles seem to have a cloying sense of sardonic amusement over the sense of tragedy he’s conveying—Afterparty, Yes, Love All—but it’s the only off-key note in the show. It’s hard to imagine work that offers a better fusion of representation and abstraction. Wylie’s style adopts the ragged structures of decay and collapse to accentuate paint’s ability to physically convey life, energy, and a fresh vision of the world.

October 15th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Edwin Dickinson, Elizabeth Finney, 1915, oil on canvas

October 12th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Dahlias, Just Opening

One last painting for the two-person show, with Brian O’Neill, at Oxford Gallery, opening next week. I put in eight hours on it yesterday. Don’t know if Jim will have enough wall space, it’s kind of large, but the challenge of completing it taught me a few things about how to handle paint. Never stop learning. I grew these dahlias in our raised bed, and picked them only a few weeks ago. We’re still cutting them, and will continue until the first killing frost, maybe tonight, but I’ll be out there covering them. Maybe I should just keep a spray going, as the farmers do. If they survive tonight, we’ll probably be able to cut them nearly into November.

October 10th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Some observations on and amused reactions to the Yellowism texts at www.thisisyellowism.com/:

“In the context of yellowism every feeling is a definition of yellow, every emotion expresses yellow color only. Sadness is about yellow and happiness is about yellow too. Pain is considered as a pure expression of yellow, orgasm as well. Inside the context of yellowism all emotions and feelings . . . images can arouse in potential viewers, express yellow color and nothing more.”

What they’re saying resembles both the erasure of all value—everything is reduced to yellow dust, basically—or the elevation of everything to one monotonous Truth. Both extremes force you essentially to give up the discriminations you normally cling to as a source of meaning and value. All art is about the same thing. Everything is either nothing or everything is holy. Take your pick. They have eliminated the dilemma by saying everything is simply about “yellow.” What you lose, in any case, is the system of values that elevates one thing over another in the world of art—or the world in general. (I find myself agreeing with both sides of this, both for and against what’s implied here.)

Consider yellowism as a totalitarian system. Two young “dictators” – authors of the definition and manifesto of yellowism decided that there is only one interpretation in this specific context. Everything is about yellow – this is the order, the final solution. It is imposed on you, you are not free to interpret, and you have to accept the only possible way of seeing things. This way and no other way.

This makes me laugh. Since nothing really changes in works of art itself when the Yellowists get busy with it. It remains the same. The art is regarded from a new context, that’s all. Yellowism is simply an assertion that all art is ultimately about “yellow color” without disturbing the diversity of meaning and interpretation that thrives in the hothouse world of art to such little effect on the course of most human lives. They stand above this hothouse and look down with amusement, pairing their fingernails.

That’s obvious that a monkey doesn’t see differences between ordinary reality, art and yellowism; it just MORE

October 10th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Loren Bouchard, creator of Bob’s Burgers

Occasionally, almost at regular but distant intervals, Marc Maron talks about art and painting on his excellent podcast, WTF. In episode 319, he interviews cartoonist, Loren Bouchard, about his life and briefly their conversation gets truthful about the life of painting in a way I love, on principle, even though I hate hearing the truth. Always. (I much prefer the delusional dreaming part, which usually leads into trouble. Like a devotion to painting, for example.) Don’t bother reading on if you’re looking for encouragement. (Praise I like. Always welcome. Encouragement I tend to laugh at. There’s no pot of gold at the end of this oily rainbow.) Painting is not an activity that makes sense, generally, as a way of life, even though I’ve been treading this painting path for decades. It’s good to keep in mind, during a journey like this, MORE

October 10th, 2012 by dave dorsey

October 10th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Rothko Homage 2 Yellow

Remember when John Goodman, in The Big Lebowski, discovered he was facing philosophers when he thought they were only three dweebs who used ferrets as weapons and dressed like Dieter hosting Sprockets on Saturday Night Live? His reaction: Oh my god, not nihilists. We’re fucked. You best listen to Mr. Goodman if you’re deeply invested in the world of contemporary art. It would be a sensible reaction to Vladimir Umamet’s recent act of vandalism at the Tate Modern where he tagged one of Rothko’s Seagram’s paintings and thus, by his own philosophy, turned it into a painting about nothing but the color yellow. I find myself oddly amused and cheered by his act of Yellowism. I doubt that it’s going to knock anything off the rails in the art world in the short term, but it may help free up some individuals to start making art without trying so hard to consciously make it mean something. And it might get a few people out of the art game altogether. If you can be talked out of it (and you should be, trust me) you shouldn’t be doing anything as nutty as making art to begin with. Art should be like the Zen monastery where they chase you away fifty times and then finally let you in out of pity because they finally realize you just can’t help it.

Thanks to my Brooklyn friend Lauren, who is a bit of a yellowist herself, but is in denial about it (so far this evening anyway), I started reading up on Yellowism. The manifesto is an interesting, monotonous and nihilistic incantation that keeps asserting its authors’ right to reduce all art to nothing more than a symbol for the color yellow. Umamets and Marcin Lodyga—the founders of yellowism—amiably claim their “new context” for art nullifies everything in art so that all art means nothing but the color yellow. In the context of yellowism—in a yellowistic chamber, as they put it—all meanings, all diverse significance, all styles and shapes and mediums, signify nothing but yellow. By tagging the Rothko and then surrendering to police, Umamets was calling attention to his philosophy and also leaving behind a painting that didn’t feature much yellow but was about nothing but yellow. Rothko may have thought otherwise when he was hard at work on his subversive painting, commissioned for the Four Seasons restaurant. He wanted it to be oppressive, part of a suite of paintings that would surround and envelope the restaurant’s patrons with Rothko’s especially unsunny weltschmerzen. I stood in that Rothko room last year at the Tate Modern, when I had a painting in a London pop-up exhibition, and I didn’t stay in that place for long. The whole museum felt like a prison: cold, imperious, and impersonal. Rothko did the paintings, now hanging in that room, right before he killed himself. By putting his mark on the work, Umamets was claiming to make the painting about nothing but the extremely sunny color yellow. (Though there’s nothing sunny or unsunny about yellowism itself. It’s the color of what should have been swirling at the base of Duchamp’s Fountain, for one thing and Umamets claims to be doing to Duchamp what Duchamp did to art: recontextualizing. If Duchamp can say a urinal is art, then Umamets can say any work of art is about nothing but yellow, simply by surrounding it with a new context. That’s the logic, and it’s cleverly seductive, a bit of a chess move, which is also Duchampian.)

Here’s the thing, as Alec Baldwin says way too often now. These nihilists are basically threatening to get yellow on your ass. The act of vandalism was small potatoes. The philosophy behind it is saying art itself has reached a point of exhaustion, a dead end, where meaning and purpose is so fungible that it doesn’t really exist anymore. Hey, tell me about it, Vlad. The tract about Yellowism is something to enjoy and even skim with a bit of wicked glee–it’s very funny in places and the Russian accent is perfect. As you do, think, along with me, it’s about time. They’ve pushed postmodernism to a dead end, particularly postmodern criticism. What Yellowism leaves in its wake, if you recognize the absurdity of the kind of critical thought the yellowists are attempting to skewer and also to take to its ultimate extreme, is something only an individual artist can answer through the act of making art. A yellowist says all works of art can be reduced to nothing but metaphors for the color yellow and they can make art works mean yellow by simply placing them in a “yellowistic chamber.” (Of their monomaniacal critical thought.) It’s a quick and dirty deconstruction of art in the most simplistic way. In my view, whatever can be reduced to the color yellow in a work of art, when a yellowist gets done with it, was beside the point to begin with—what actually matters will always resist interpretation as content. The yellowists don’t go so far as to say this, but by taking all ostensible meaning in art and reducing it to the color yellow, they force you to realize that this is where postmodern criticism leads, the arbitrary domination of the critic over the work itself, as well as the tired dominion of the intellect over a mysterious, yet integral act of imagination.

More on this tomorrow.

October 3rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

Sleeping Cat, Chris Baker

When I stopped in to pick up one of my paintings from the back room at Oxford Gallery yesterday, I couldn’t stop looking at Chris Baker’s new paintings. He’s one of three outstanding artists on view in Water Works. All three are exploring the power of a water-based medium with amazing skill. Chip Stevens’ assurance with watercolor reminds me of a Japanese or Chinese painter’s fearless, irrevocable brushwork and use of negative space. And Barbara Fox’s images obsessively and meticulously return to glass globes strewn across surfaces they absorb and reflect. They struck me as a visualization of a heightened state of mind where the boundary between self and other has dropped away—no small achievement for what are essentially highly realistic still lifes. So I’m not doing justice to the masterful work of his co-exhibitors by focusing on Baker, yet Baker’s work calls for celebration in a special way because I’m finally beginning to feel what he’s up to. I’ve always admired his prolific ability to evoke light and form as well as a more ethereal sense of time and place in his scenes, but often I’ve wanted MORE

October 2nd, 2012 by dave dorsey

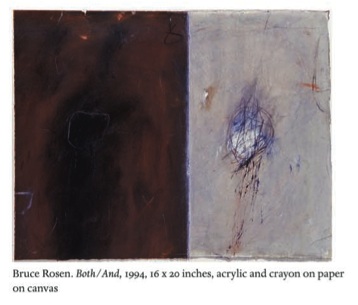

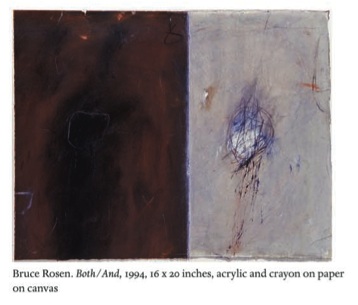

The latest group show at Viridian Artists, which came down a week ago, introduced me to an artist the gallery represents posthumously, someone whose work I’d glanced at in the past but hadn’t really seen. The show opened my eyes and heart to the subtle depth of Bruce Rosen’s work. His wife, Maxine, has been keeping her faith in his work alive by maintaining a long-standing membership at Viridian on his behalf. The Viridian website appears to be the only place you can get some idea of what he was doing in his quiet, philosophically sophisticated drawings in various media, mostly gouache and chalk on paper. What I’m having difficulty admitting is that this process of having my eyes opened has made me rethink, in some respects, my general philosophy of how art ought to operate on a viewer. This slightly puzzled admission is laden with paradoxes I’m not sure how to sort out—more on that in a bit. These new mental adjustments remind me of conversations I had earlier this year with A.P. Gorney in Buffalo. One of his personal tenets—art is not visual—stuck in my craw because for me painting needs to work subconsciously in an exclusively visual way, a peer-to-peer connection, as it were, right brain to right brain, leaving the left brain out of the conversation entirely. It’s my extreme response to the decades of conceptualism in art, which now seems to have MORE