Archive for October, 2013

October 29th, 2013 by dave dorsey

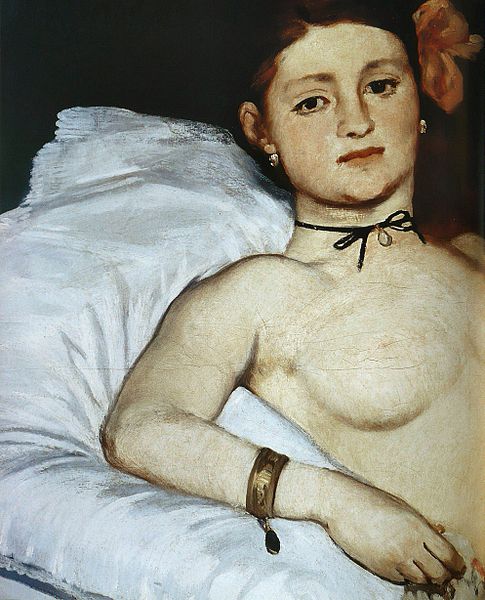

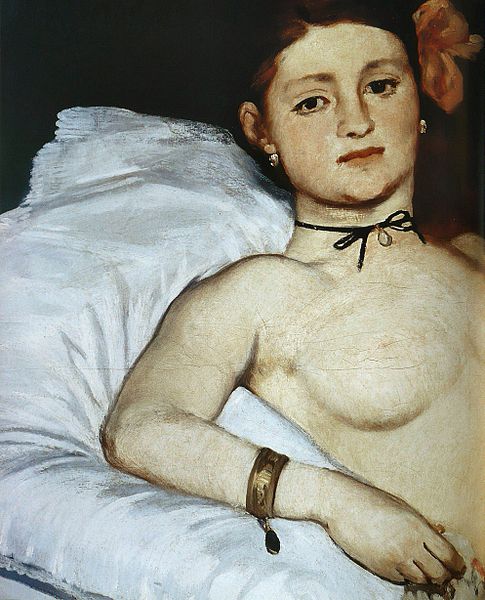

Olympia, detail.

From David and Goliath, Malcolm Gladwell’s new book, published earlier this month:

There are in Paris scarcely fifteen art-lovers capable of liking a painting without Salon approval,” Renoir once said. “There are 80,000 who won’t buy so much as a nose from a painter who is not hung at the Salon.”

When the artist Jules Holtzapffel didn’t make it into the Salon of 1866, he shot himself in the head. “The members of the jury have rejected me. Therefore I have no talent,” read his suicide note. “I must die.”

in 1865, the Salon, surprisingly, accepted a painting by Manet of a prostitute, called Olympia, and the painting sent all of Paris into an uproar. Guards had to be placed around the painting to keep the crowds of spectators at bay.

in 1968, Renoir, Bazille, and Monet managed to get paintings accepted by the Salon. But halfway through the Salon’s six-week run, their works were removed from the main exhibition space and exiled to the depotoir–the rubbish dump–a small, dark room in the back of the building, where paintings considered to be failures were relocated. It was almost as bad as not being accepted at all.

Did they want to be a Little Fish in a Big Pond of the Salon or a Big Fish in a Little Pond of their own choosing? In the end, the Impressionists made the right choice.

The Impressionist’s exhibition opened on April 15, 1874, and lasted one month. “We are beginning to make ourselves a niche,” a hopeful Pissarro wrote to a friend. “We have succeeded as intruders in setting up our little banner in the midst of the crowd.” Their challenge was “to advance without worrying about opinion.”

October 28th, 2013 by dave dorsey

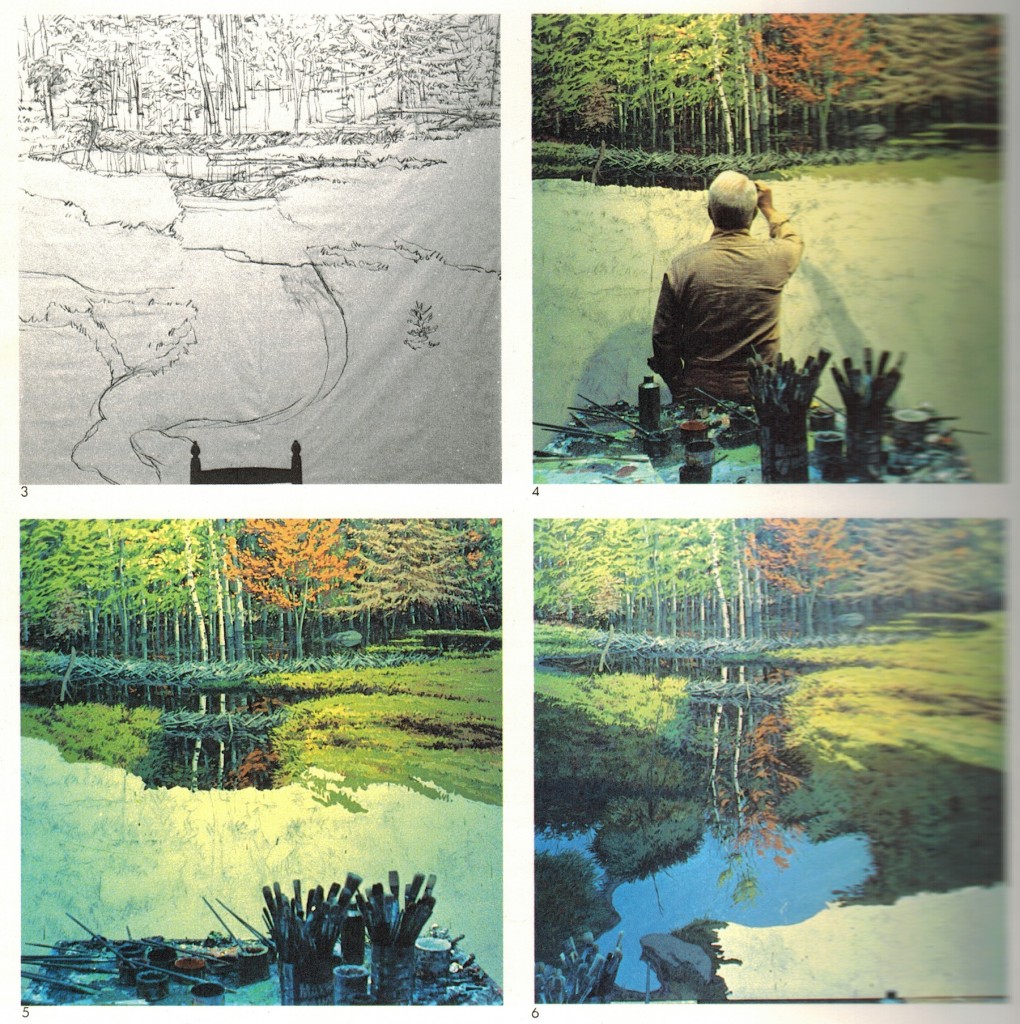

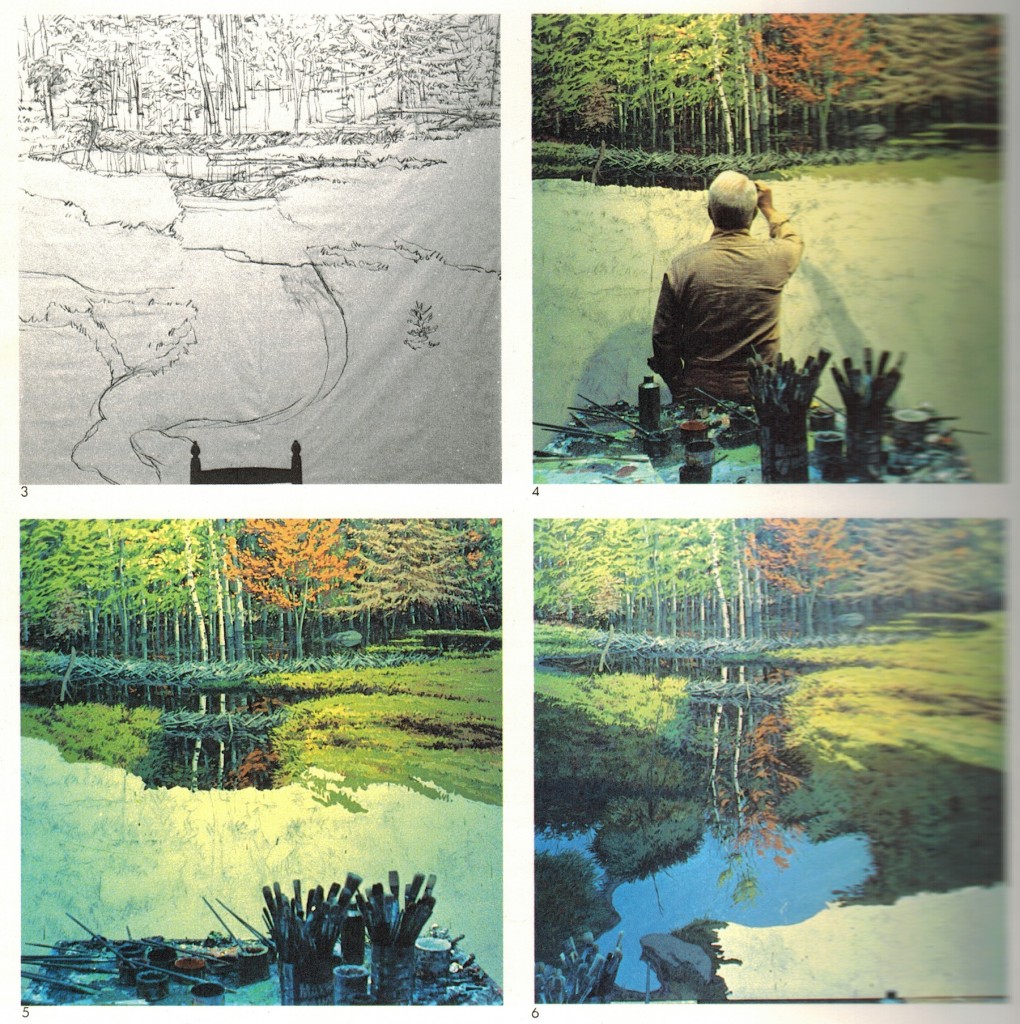

Top to bottom. How Welliver painted, from Realists at Work.

As promised, here are interesting comments from Neil Welliver, this time from an interview in The Art of the Real, edited by the poet Mark Strand. As with the previous Q/A, some of what he says I listen to a little more skeptically than when I first read these books. He criticizes 19th century art on terms that seem to partly apply to his own painting, it seems, which strikes me as “systematic and structured”—isn’t almost all painting structured?—but in a good way. I understand what he’s saying: the painters he dislikes respond less to individual and particular qualities of a scene and do whatever they’ve learned to do in a uniform way. They become tree-painting factories, and don’t need to observe actual trees in order to do it. He says he responds to the particularity of a given place so that “generalities are wiped out of your life” but his method, reducing his technique to such a limited selection of colors, tends to create a “feel” when you look at one of his pictures, common to all of them. So his style generalizes areas of an image because of the way it simplifies what he sees: generalizing within a discreet area of color is what he does. (That isn’t what he means of course but I can here ironies in what he says now.) The particular variations between one Welliver and another seem slighter than what all his paintings have in common, which is what he learned from Abstract Expressionism. Even so, reading these interviews is a great way to understand a little better what you’re seeing with the Wellivers on display right now at the National Academy Museum:

In Maine there is an extraordinary clarity. You can look for a mile but objects seem right before your face; you can identify them. I’m interested in the character of the light—that northern flat light—where the sun doesn’t get very high. A lot of it is geologically young. The upheaval is still apparent, the gouging of all the glaciers, all of that. I paint what would, in terms of theater, be considered innocuous and banal—ordinary places. I could not paint where the landscape doesn’t interest me, where it’s not complicated enough, where it’s been too ordered by people.”

Hudson River pictures look to me procedural, systematic, structured, MORE

October 27th, 2013 by dave dorsey

October 24th, 2013 by dave dorsey

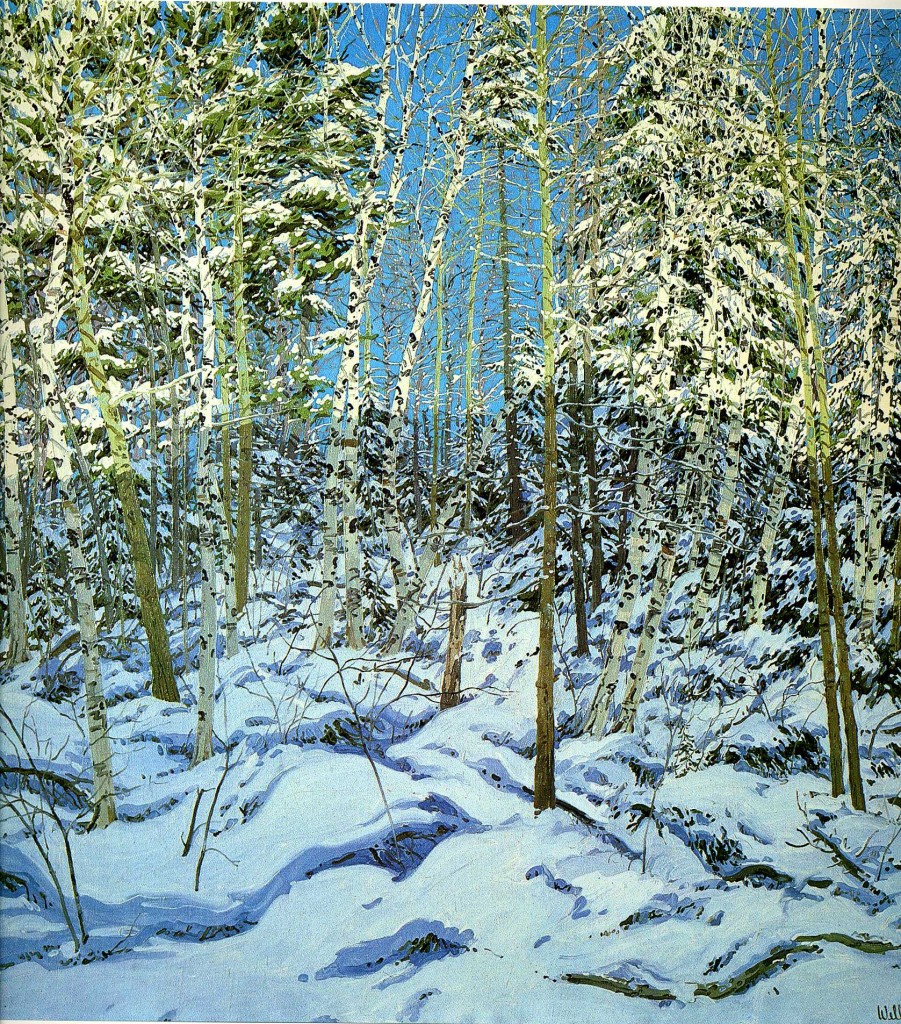

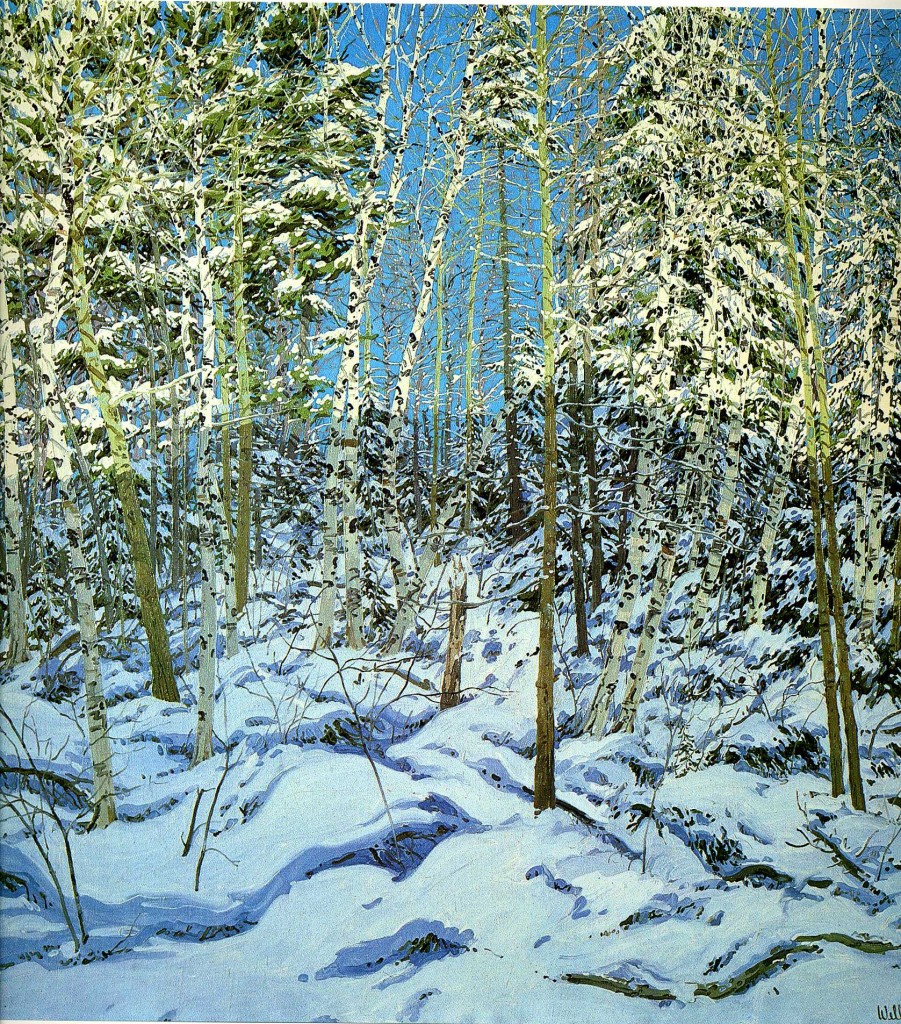

Shadow, Neil Welliver

I’m still meaning to write at more length about the current show at the National Academy Museum, and how it gave me a first glimpse, after all these years, of work by Neil Welliver, Stanley Lewis, and Albert Kresch, as well as Paul Resica, whose beautiful work I’d seen here in Rochester, and three other related post-war artists. But seeing Welliver’s huge landscapes for the first time reminded me of two fairly extensive interviews he did in the 80s, much of which I’m going to reproduce here, in a couple posts, which is probably in violation of fair use. The books appear to be out of print, and often priced more expensively than most people would be willing to pay, so if there are any copyright issues, they won’t have much of an economic impact. (Represent ain’t Napster.) I haven’t made a penny off this blog for the two years I’ve been writing it, so I think I could be forgiven for passing along Welliver’s thoughts to the few people paying any attention. Plus, these coffee table books are valuable primarily for the great color reproductions of paintings as well as photographs of artists at work in their studios—and you’ll have to resort to Amazon for that. The books Art of the Real, edited by Mark Strand, and Realists at Work, by John Arthur, were both published in 1983, and I bought them a few years later. If you’re a representational painter, they’re indispensable books. I’ve returned to them repeatedly over the years for inspiration and to reread the interviews with Neil Welliver which had as strong an impact on me as his paintings did when I discovered these books. In these pages, for the first time, I set eyes on work by William Bailey, Janet Fish, Louisa Mattiasdottir, Lennart Anderson, Ralph Goings and William Beckman: a world of possibilities and a treasure of information and insight back when I was just settling down and trying to get my bearings as a painter after many years of doing whatever I felt like doing at the time, a tendency I haven’t completely lost. (I’m a slow learner.)

This past week, I returned to the interviews with Welliver in both books MORE

October 23rd, 2013 by dave dorsey

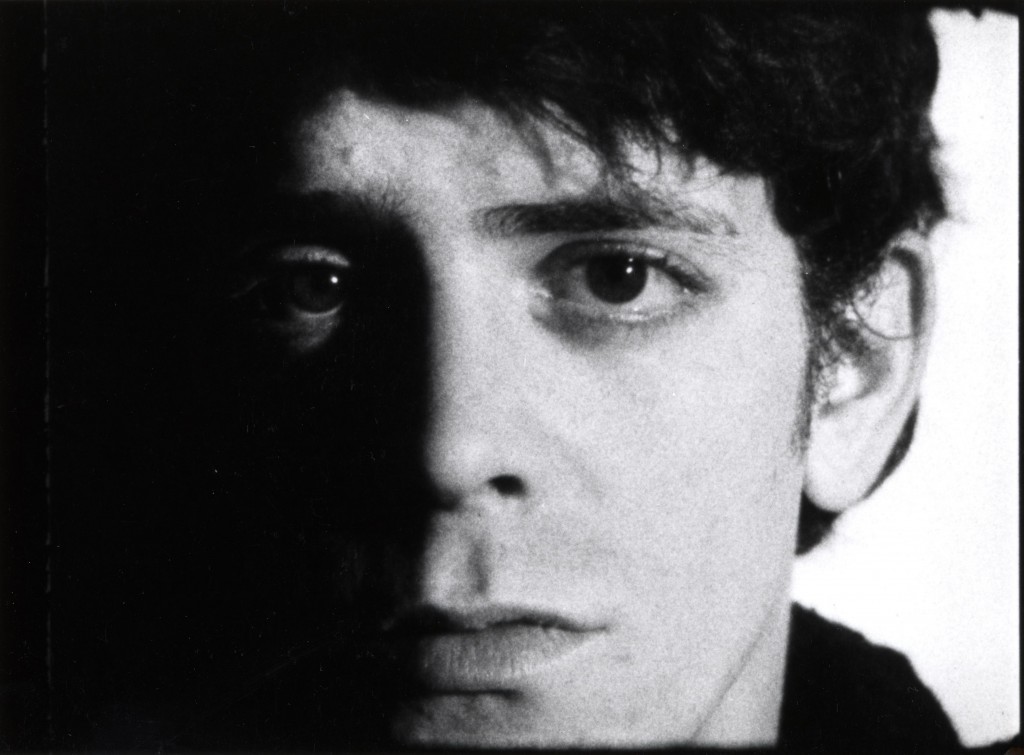

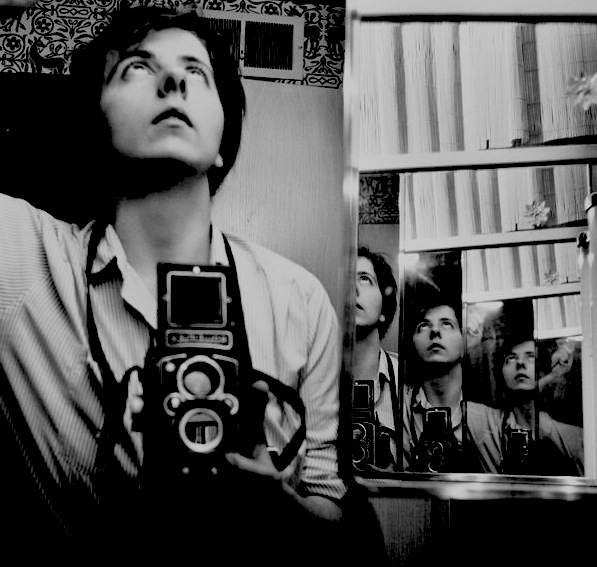

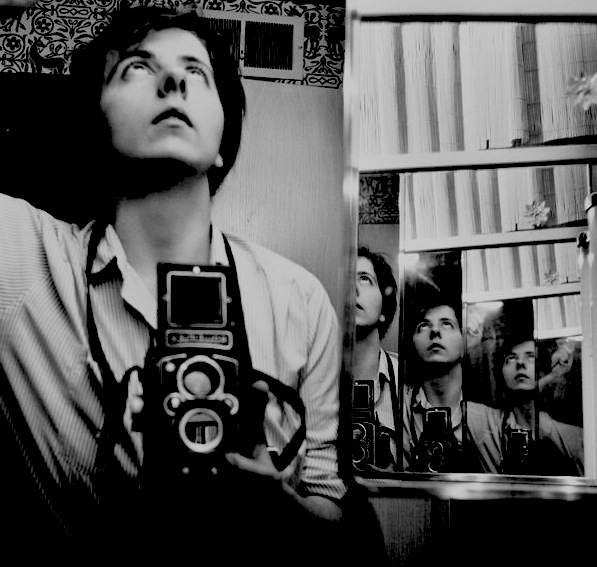

Vivian Maier, Self Portrait

From a story in Sunday’s New York Times about the universality of self-portraiture thanks to “selfies.” This androgynous self-portrait by Vivian Maier, one of over 100,000 pictures she took, makes her seem even more interesting. I’ve adjusted it to match the way it was printed in the paper edition (with higher contrast and darker exposure). Maybe I’m superimposing El Greco onto those eyes. One of my many regrets: not being able to spend five hours in a coffee shop, listening to Vivian Maier talk about her photography.

October 22nd, 2013 by dave dorsey

Tangled Palms, Bonnie Wolsky

“I treat each shape as a painting in itself.” –Bonnie Wolsky

The current show at Oxford Gallery, Frame of Reference, submits for your consideration the work of eleven artists as evidence for James Hall’s curatorial thesis that all abstract art is, at some level, representational. The eye instinctively struggles to recognize a figure in the carpet, as it were, and this reflexive impulse gives the best abstract work a vital tension as the mind tries to reconcile the abstract patterns with what the mind imagines it sees, based on them. The work is all excellent, yet, as if to confirm what Hall says about abstraction in the fine catalog he produced for the show, the paintings that most captivated me were also the most literally representational. Bonnie Wolsky’s all-over watercolor images of tangled palm fronds work as finely rendered realistic images as well as purely abstract patterns of line, value, and the extremely restrained hues of precious metal. She works from photographs as a source, but improvises and alters what she sees as she goes. Her fronds cascade down the paper in spidery streaks and they often shimmer and gleam like hair in a shampoo ad. It’s quietly seductive, so quiet that you can walk through the gallery and glance at them without staying long until you come back and suddenly pause long enough to see what’s there. Each strap-like frond is rendered with all the care of a distinct, separate object in a still life: she draws flawless long outlines and then works within them, improvising with color, sometimes (I’m told) dropping grains of salt into the drying paint to create little crystalline patterns, like frost on a window. What’s so immensely persuasive about the work is how it’s simultaneously so flat and yet so deep: the eye and mind are constantly flipping back and forth between a recognition of the abstract pattern and the sense of three-dimensionality created by the areas of dark background, peeking through the fingers of palm, or shining off little foreshortened areas where the fronds swerve away from the viewer into the depths behind what seems to be hanging on the actual surface of the paper. The effect is meditative and spiritual, as light shines up from within a thicket of dried vegetation, transforming the dead material into lustrous hues of platinum and gold. In short, it’s alchemy. Go to see all the work in this show, but pause long enough at Wolsky’s work to really notice what’s there.

October 20th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Marina Abramovic

Contemporary art so often makes me pleased that the greatest existential questions I face as an artist often come down to: “Do I dare to paint a peach?” This is a nicely balanced story about a performance artist who is something like a less-ironic Warhol for our time, and it appeared on the front page of the Sunday New York Times waiting for me this morning in my driveway. Simply reading a story about any visual artist, let alone a performance artist, on the front page of the Times is like sighting a rare bird, so it’s quite an achievement in celebrity, but it’s hard to read the story without laughing both appreciatively and, more often, whilst shaking one’s head. It’s occasioned by Abramovic’s intent to build an institute for mind-and-body-cleansing in Hudson (where David Byrne said he might move to join the “expat hipsters” fleeing New York City). Here are some choice moments in the story:

Mistrustful and possibly envious, some performance artists and critics are accusing Ms. Abramovic of cultivating something suspiciously like a cult of personality. She seems so enamored of the spotlight, they say — so caught up in dancing with Jay-Z, doing mind-cleansing exercises with Lady Gaga and hanging out with James Franco — that she is in danger of disappearing down the rabbit hole of her own mythology, betraying not only her own roots but also, perhaps, the true nature of performance art itself.

“I respect Marina a lot in the overall sense, but I think the art world has lost its mind,” said Amelia Jones, a professor of art history at McGill University. “I keep wondering what’s next — is she going to set up her own small country somewhere?”

Marina: “Now I understand that my work is not my work anymore. It’s about culture in general, about changing the consciousness of human beings on this planet.”

In conversation, she leans in close and speaks with an intimate urgency, her voice a low, soft, Slavic-accented purr that brings to mind both Christiane Amanpour and Natasha the Eastern Bloc cartoon spy.

“One idea is to take 250 drops of blood of the most important human beings on this planet who contribute to humanity — in science, technology, writers, filmmakers, whatever,” she said. Once a year, “the most important shaman of that century,” she explained, would energize the blood drops, using the “life force” that connects body to blood.

As she says, the possibilities are endless.

Endless possibilities. Yes. It’s been a great opportunity and a great curse of art for more than half a century, hasn’t it?

October 19th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Neko Case

When it came out, like a lot of people, I fell in love with Fox Confessor Brings the Flood. It has that feel of originality that albums back in the late 60s and early 70s had: when it seemed to be easier to record things that sounded utterly unique and new. Plus she has that voice like the wind in the Rockies, as Garth Hudson put it. She can write and sing like few other women, and, as it turns out, she can talk, too. She’s friendly and funny, in the conversation she had with The Nerdist about a month ago. Not just witty, but quick and completely, unguardedly open about how she responds to people and things. She’ll say absolutely anything that crosses her mind. Yet she can also pull back and offer small, unexpected and seemingly innocuous observations that would hardly register with most people. At the end, the conversation goes this way about when she was a little girl and visited Disneyland:

You know what the most amazing thing about Disneyland is? (This influences the rest of my life. I still think about it.) Waiting in the line for Pirates of the Caribbean there are these cat tails in between you and the restaurant. And they had these fake fireflies that would light up. I don’t know if they’re still there. And I just remember being, like, that’s the coolest thing I’ve ever seen. If I could explain to anyone my entire artistic aesthetic, that’s it right there. You made me fireflies, Walt Disney, so that when I was waiting to eat that disgusting burger in there I would have these fireflies.

Now, this is not the persona she projects in most of her music, but it’s the person who’s actually there in those songs. Add Christmas tree lights to the fireflies and that pretty much sums it up for me, as a painter. I think of my parents the way Neko Case thought of Walt Disney: they gave me fireflies and Christmas tree lights in East St. Louis so I had something to look at while I was waiting for the rest of our lives to happen. Fireflies in a jar . . .

Favorite song on her new album: “Calling Cards.” (She also talks about touring with nice-guy and funny man Nick Cave, and speculates about lathes in a way that would cause Ron Swanson’s brain to seize up on a number of levels.)

October 18th, 2013 by dave dorsey

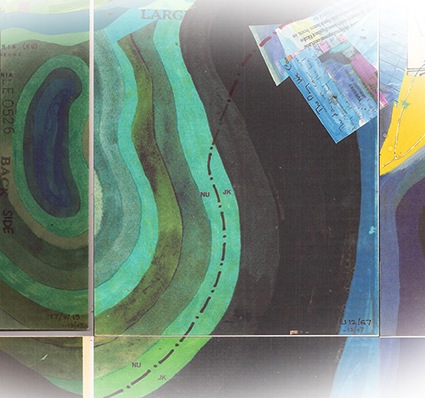

Rudge Whitworth, Robert Mielenhausen

Robert Mielenhausen’s solo show is up at Viridian Artists with an opening this weekend, and I’ve been looking forward to it ever since it was delayed after Hurricane Sandy did a number to his house and studio last year. He’s back on track now, and has been doing additional work that looks even more interesting than what he had planned to show a year ago. Jerry Saltz actually stopped in to see Mielenhausen’s previous show at Viridian a couple years ago—the indefatigable Lauren Purje, who was overseeing the opening reception, recognized him on the elevator in the building, and, having friended Saltz on Facebook, invited him to take a look. Saltz liked some of what he saw, but not enough to write it up. He should check out the new stuff. Mielenhausen has found channels to reach some collectors in NYC who’ve bought his work recently, and he deserves to be better known.

Mielenhausen focuses on merging photography and painting in a way that allows him to experiment with materials—emphasizing the texture of the surface. He paints on hollow lauan doors, the kind you can get at Home Depot, sealing them and then aging and weathering them with compounds that he spreads over the surface and lets dry in different ways. That surface is one part of a tension between opposing qualities that he sets up, at various levels in each piece: photography vs. painting, abstract surface vs. representational illusion, and universal vs. particular. The show is a series of images of bicycles he has come across and photographed in New York City, and the images capture not only the human quality of the bikes—most have been heavily used and have the character of an old pair of jeans molded to the wearer’s body—but also a sense of time of day and season. His use of color is especially subtle and evocative, beautiful but in a reserved way that seems to bring out the feeling of the place and the time of the photograph. Though the work is formally experimental, it feels natural, a glimpse of a recognizable moment in ordinary daily life: a visual haiku.

I talked with him briefly this past week about the show.

You developed a lot of your techniques as teaching experiments, right?

Working with students I began to develop this technique and began to pursue it myself and pushed it further with found objects and by making partial MORE

October 17th, 2013 by dave dorsey

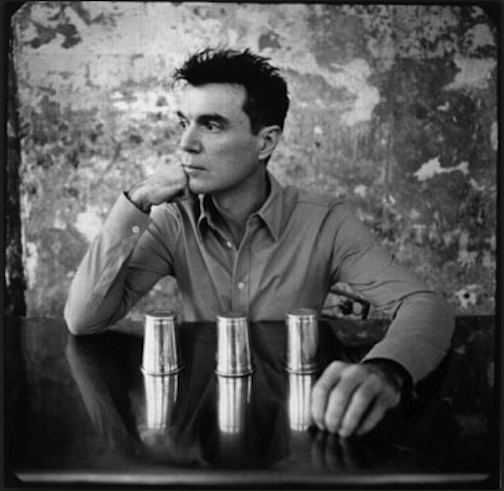

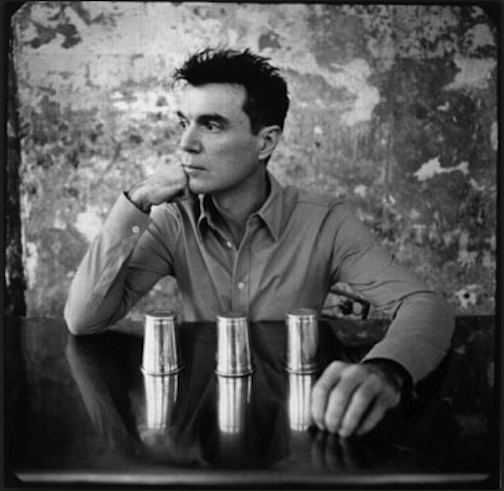

David Byrne

“Many of the wealthy don’t even live here. In the neighborhood where I live (near the art galleries in Chelsea), I can see three large condos from my window that are pretty much empty all the time. What the fuck!? Apparently, rich folks buy the apartments, but might only stay in them a few weeks out of a year. So why should they have an incentive to maintain or improve the general health of the city? They’re never here.

This real estate situation – a topic New Yorkers love to complain about over dinner – doesn’t help the future health of the city. If young, emerging talent of all types can’t find a foothold in this city, then it will be a city closer to Hong Kong or Abu Dhabi than to the rich fertile place it has historically been. Those places might have museums, but they don’t have culture. Ugh. If New York goes there – more than it already has – I’m leaving.

But where will I go? Join the expat hipsters upstate in Hudson?”

The Guardian

October 16th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Amish baskets

I’ve been doing still life paintings since the 80s, and I’ve tended to rely on fairly common household objects: jars, pitchers, napkins, flowers, fruit, all standard fare. OK, now and then, a skull, but skulls are as traditional as you can get in Western art. Like Chardin, I return again and again to a limited set of objects. We owned a couple baskets years ago—one of them survives in my wife’s classroom at School #43 in the city of Rochester, but we lost the other one in our last move. I’m reminded of that lost basket every time I visit my parents at their place in Florida, where a painting of it hangs in their dining room. Thinking about a show I’m preparing for next year, I wondered if I could find something like that lost basket on the Web, and I began a search using various words until for some reason I remembered that the style of that basket was Amish.

I found www.amishbasketweaver.com and picked out three baskets that were as close as I could get to the one I’d painted before. The site sells crafts from an Amish community in Tennessee. (Two of the baskets are in the photo above, on the left; the larger one on the right I found on eBay.) So I ordered the baskets and forgot about them for a few weeks. When I realized the baskets hadn’t arrived, I wrote a friendly note asking if things were still on track. Lydia, who wrote back, hinted that a particular person was still weaving them for me: Mary Mast. I said there was no rush. A week or two later, the baskets arrived in an old, spavined box, nestled in egg cartons, in perfect condition.

I wrote back to Lydia: “The baskets arrived today. Beautiful work. Thanks very much.”

She replied: “I’m happy you are pleased with Mary’s workmanship.”

“Definitely,” I said. “My compliments to Mary.”

I think those few additional words for some reason triggered what came next, which completely changed the way I look at those baskets now, sitting on our kitchen counter.

“Thank you so much for your compliments—I will be sure to tell Mary when next I see her. She is a widow with nine children; Alvin died a year ago this past July—her only income is making baskets and selling her baked goods. Mary is a very inspirational human being—Alvin was permanently disabled in a farming accident 13 years ago, and Mary was the devoted wife, taking care of him, the farm and the children. She never complained about her lot in life, but is so incredibly loving and tender-hearted. She epitomizes ‘selflessness’. While Alvin was still alive, she would take care of him on Saturday mornings, load up her buggy before daybreak with all her baked and canned goods, and her baskets and make the six mile trip to the Amish Auction barn. Once there, she had to set up her tables and load these with her goods to sell to the tourists. She did this every Saturday regardless of weather, because their farm is so far off the beaten path, the tourists never find them. We set up the amishbasketweaver.com website to help her sell some of her baskets after Alvin’s accident—it is something of a nuisance trying to find boxes for shipping, but if it helps this struggling family, it is worth the work—it certainly doesn’t come close to comparing to the load Mary must carry.” MORE

October 15th, 2013 by dave dorsey

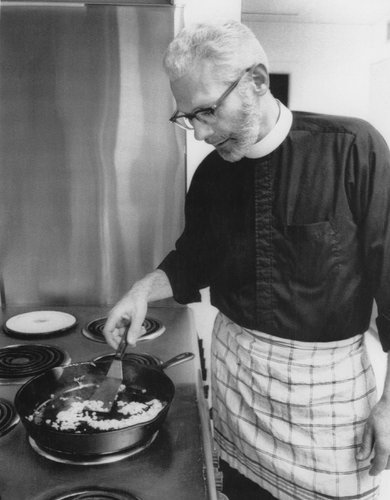

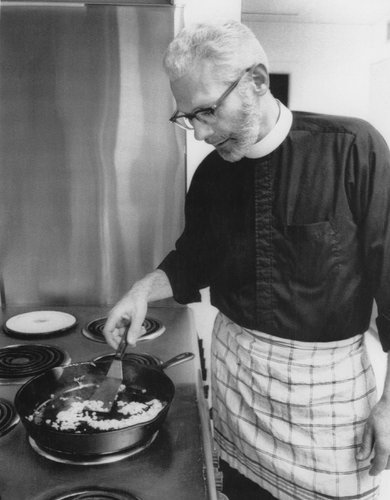

I ordered Supper of the Lamb last week, and Amazon told me it wasn’t supposed to get here until November, but it arrived today. I had no idea that he’d died, until I went searching for his photograph in order to post this:

The man who said “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” was on the right track, even if he seemed a bit weak on the objectivity of beauty. He may well have been a solipsist who doubted the reality of everything outside himself, or one of those skeptics who thinks that no valid judgments are possible, that no knife can in reality be pronounced sharp, or any custard done to perfection. It doesn’t matter. Like Caiaphas, he spoke better than he knew. The real world which he doubts is indeed the mother of loveliness, the womb and matrix in which it is conceived and nurtured; but the loving eye which he celebrates is the father of it. The graces of the world are the looks of a woman in love; without the woman they could not be there at all; but without her lover, they would not quicken into loveliness.

There, then, is the role of the amateur: to look the world back to grace. There, too, is the necessity of his work: his tribe must be in short supply; his job has gone begging. The world looks as if it has been left in the custody of a pack of trolls. Indeed, the whole distinction between art and trash, between food and garbage, depends on the presence or absence of the loving eye. Turn a statue over to a boor, and his boredom will break it to bits–witness the ruined monuments of antiquity. On the other hand, turn a shack over to a lover; for all its poverty, its lights and shadows warm a little, and its numbed surfaces prickle with feeling.

Or, conclusively, peel an orange. Do it lovingly–in perfect quarters like little boats, or in staggered exfoliations like a flat map of a round world, or in one long spiral, as my grandfather used to do. Nothing is more likely to become garbage than orange rind; but for as long as anyone looks at it in delight, it stands a million triumphant miles from the trash heap.

–Robert Farrar Capon, 1968, The Supper of the Lamb, a cookbook, among other things

October 15th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Banksy does a little playful subversion of art pricing. He can certainly afford it, as long as it’s a prank confined to Central Park.

October 14th, 2013 by dave dorsey

I got to know Lauren Purje when I served as her pack mule, along with Rush Whitacre when we helped move Viridian Artists from its old space on West 25th St. to its current digs on 28th. Well, a lot of good that did. This wily one is heading back for a solo pop-up at EMOA Space, now presiding in our old suite at 25th,. Doh. It’s a week-long exhibit, and she told me she thought about doing an installation for it, yet it’s likely to be primarily a way to see what she’s up to with her new paintings. My two cents was: do an installation and show the paintings. We’ll see. In her paintings, she melds her own contemporary preoccupations into Romantic landscapes—she swoons for Turner—with an occasional skull seemingly manufactured offshore by Durer and then imported into Brooklyn via time machine from Renaissance Germany. In her unstable, ambiguous world, the comic Purje persona appears as a diminutive focal point, interrogating or just suffering her natural surroundings, which might contain a few badass stowaways on the time machine, such as a stray T Rex. Her humans enjoy about the same allowance of space, and influence, vis-a-vis the rest of the world, as they would in a Chinese scroll painting. She has somehow stirred a little Charles Schultz into a full shaker of Samuel Beckett for a cocktail to ease enchanted and amused brooding about subjects otherwise off-limits. Her heart sides with Schultz, not Beckett, as much as she would like you to believe otherwise.

I was disappointed when she told me she doesn’t plan to exhibit any of her original drawings for the weekly comic she does at Hyperallergic. I tried to tempt her by saying I’d have shelled out some cash for the drawing she did where her persona was sleeping on the floor in a fleeting ray of sunshine through the window. No dice. That drawing had a cutline more or less as follows: “I don’t own a cat, but we have certain interests in common.” (She owns two cats now, hence a collectible!) It’s my favorite Purje, now lost forever she claims. (Bet not.) Her drawings are a subtle form of self-exposure, a la Jeffrey Brown—who once sent her a hand-written note which, when she found it in her clutch of U.S. Postal Service junk mail that day, caused her to bounce around her apartment as if it were a mosh pit. Her comics convey a refreshingly self-deprecating skepticism about her own inclinations while gently skewering the art world in general. In other words, she may be hard to pin down on the actual facts of her life if you ask her a direct question, but she’s unwaveringly honest and candid when she starts drawing her alter ego’s little bubble head. She’s a walking example of Fitzgerald’s maxim: “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” She’s constantly falling in love with her own life as the artist, and yet, at the same time, recognizing how much of the art world, like every other part of the world, is built on all kinds of unsavory fashions and elitisms. So she casts a cool eye on herself as she makes all the right moves for getting deeper and deeper into the New York scene. In her own life, I’ve watched her shrewdly connecting with influential art types, in remarkable ways, while simultaneously standing back and watching herself with the perspective of a pedestrian clocking a minor fender bender. She loves what she does. She hates what she does. Note the Transylvanian cape in the drawing above. Oh, Godot. It’s that “first-rate intelligence” that shapes her comics. She may be a moving target in actual life for anyone who tries to get a fix on her—but in her drawings she has an unerring bead on her own ink-pumping heart.

Opening reception: Saturday October 19th, 6-8pm., 530 W 25th St. #407

October 13th, 2013 by dave dorsey

A new performance from Vernita N’Cognita, from the email announcement I got from Franklin Furnace and the press release at Soho20:

“You never know the value of a moment until it is a memory”

Dr.Seuss “One doesn’t recognize the really important moments in one’s life until it’s too late.” Agatha Christie

Vernita N’Cognita presents “A Moment”

7PM Thursday October 17, 2013

“A MOMENT” is the newest performance work from N’Cognita. It attempts to project to the audience the deeper implications of our simplest actions and how they can alter the course of our lives. The slow-motion quality of Butoh movements allow the viewer to notice infinitesimal details and her smallest gestures. This will be the first public viewing of this work still in development. Its final form will be presented at Judson Church in January.

Vernita Nemec AKAN’Cognita began performing in conjunction with her visual practice in the late 70’s. One of her earliest performances, “Humorette”, occurred at Soho20 in 1978 in conjunction with her solo exhibit & installation there. She has studied Butoh and performance theory with many noted Japanese & American performers including Eiko of Eiko & Komo, at PICA in Portland OR with Deborah Hay & Akira Kasai, and most recently Body Resonance at Schloss Broellin in Germany with Yumiko Yoshioka. Butoh adapted forms an important aspect of her performance work.

Nemec, also known as N’Cognita to honor underknown artists, has presented more than 70 performance in the United States, Hungary, Japan, Ireland, Germany, Mexico and France, including guerrilla performances at the Pompidou Museum in Paris, Documenta 13 in Kassel, and more than 20 solo exhibitions of her mixed media collages & installations in the United States, Ireland and Hungary. Her visual art is in the collections of MOMA, the Savaria Museum in Hungary, Sylvia Sleigh Collection of Feminist Art, Rowan University, Asian American Art Center, Franklin Furnace, Groupa Junij, Belgrade and others.

Articles and reviews of her work have appeared in the New York Times, The Village Voice, High Performance, Nation Magazine & the New Yorker among other publications. Her performances can be seen on UTube and Vimeo. She is included in “The Power of Feminist Art”, 1994, Harry Abrams (Pub), edited by Norma Broude & Mary Garrard, “The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Feminist Essays on Art”, 1995, Lucy Lippard. and “Performance Artists of the 80’s” by Linda Montano. She currently lives and works in New York City.

www.ncognita.com [email protected].

October 11th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Last Word, Darryl Moody

I had a fun conversation with Darryl Moody last week at Viridian Artists. The closing reception for his solo show on the 12th—tomorrow, as I’m posting this—and the show goes down the next day. He holds a BA in Graphic Arts from the University of Illinois in Chicago, where he studied design with Bauhaus artists who had fled Germany in WWII. He went on to get an MFA in sculpture from The School of the Art Institute in Chicago. He has written “Photography as a Psychological Narrative” while working at Indiana University.

You take photographs in various cities of what people have posted and painted on public walls: street art that has been covered with other street art or printed matter. What’s interesting is how you capture the passage of time in the way these layers accumulate and then decay either because of the weather or as people successively alter what’s there. How did you get started doing this?

Ten years ago, in Baja, Mexico, a combination of things caught my interest. When I looked at street art there, I noticed how things that were posted usually deteriorated much more slowly than they would here. In New York, a lot of the imagery here disintegrates because it’s being attacked by people. The other thing that happens in Mexico, even with graffiti, they will use sharp objects, often on glass, and they’ll scrape on glass surfaces or hard surfaces in general, but they also scrape on metal. So a lot of things that were interesting initially weren’t just graffiti but the fact that they were on top of older imagery, even from the 40s. Occasionally when they would use a sharp object and write on metal, the oxidized metal would bleed through (and it would expose the older layers of material.) Also, there’s something about the light on the West Coast. When it’s a clear day, you get light that’s almost blinding. The intensity of the light made the experience much different.

You’ve been spending the three weeks of your show at Viridian wandering around taking a lot of photography in New York City. How did you get drawn to New York?

I got to New York in 2004, when I was doing a residency at Cooper Union. I was beginning to have questions about when and why does certain art become significant in art history. Where’s the edge of art criticism and how does it intersect with history?

In other words, how does art in a given period get legitimized and recognized as art?

Yes. How we arrive at determining what is art to begin with and what do we recognize as art over time? MORE

October 9th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Illusory Flowage, Neil Welliver, OIl on Canvas

When I have more time, I’ll write quite a bit more about the current dazzling show at the National Academy Museum, Say It Loud, Seven Post-War American Painters. I saw it Friday, and though I’m a guy who generally finds it impossible to stop talking (just click around on this blog if you doubt me), I was dumb-struck with awe and admiration. It features work by seven painters who aimed to reconcile representation and abstraction in a period when, as the catalog puts it, “American painters who came of age in the 1940s and 1950s were expected to choose allegiance to either abstraction or representation. As many saw it, no middle ground was possible.” These days, painter after painter–and artists working in other mediums–gravitate to that middle ground. By choosing to remain on the fringe, as it were, these painters stayed true to what is, for me, the central imperative of painting: make it simultaneously real and unreal, both a rendering of something actually seen and a physical field of paint assembled for its own sake. The show brings out how all seven painters recognized that the way forward was to make their medium and its support central to what the work is about: how painting is first and foremost about paint, even when it’s inevitably about something else. There’s so much to love in this show, and though I didn’t like all of it, it made me respect and admire even those among the seven whose work left me wanting. (We suspect the fault is in ourselves, not these stars.) More later. (I have to say that after a couple decades of admiring and envying Neil Welliver from reproductions of his work, I finally was able to see the how magnificent his paintings actually are.)

October 8th, 2013 by dave dorsey

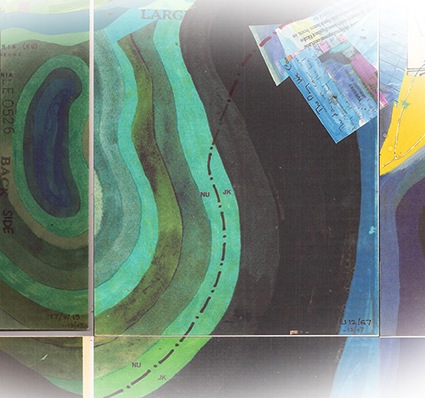

How many works of visual imagination have ever required fifty years of labor? That’s how long Jerry Gretzinger has been working on his ever-changing SimCity-like map. Hey, you have to get it right if you want the citizens of virtual Ukrania to find their way around. Google maps won’t help, yo.

How many works of visual imagination have ever required fifty years of labor? That’s how long Jerry Gretzinger has been working on his ever-changing SimCity-like map. Hey, you have to get it right if you want the citizens of virtual Ukrania to find their way around. Google maps won’t help, yo.

October 7th, 2013 by dave dorsey

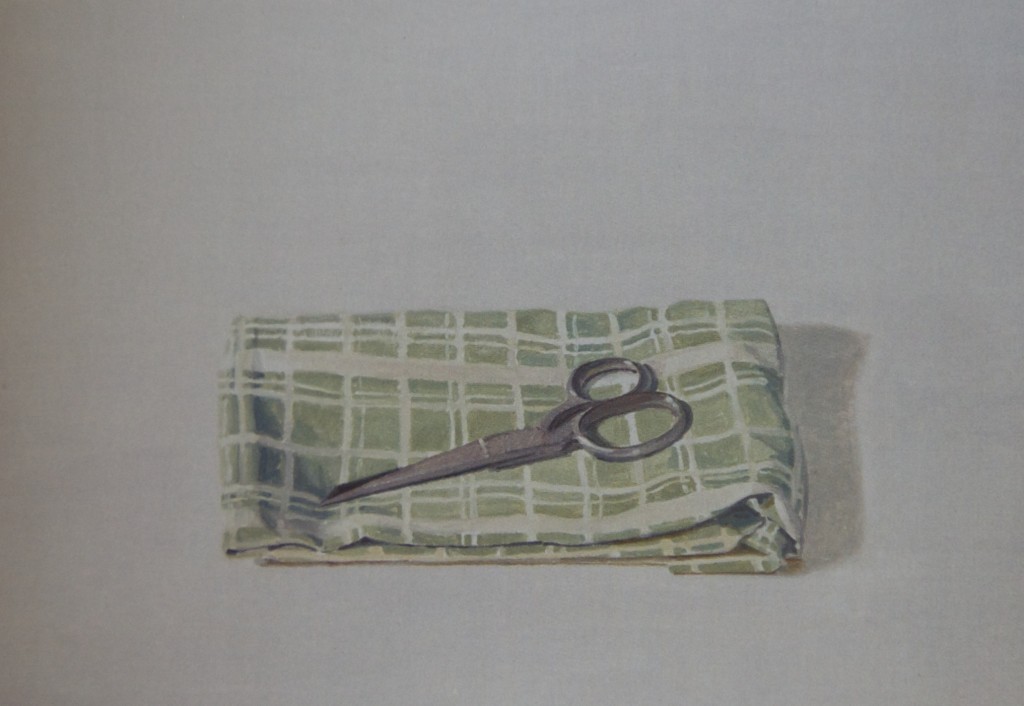

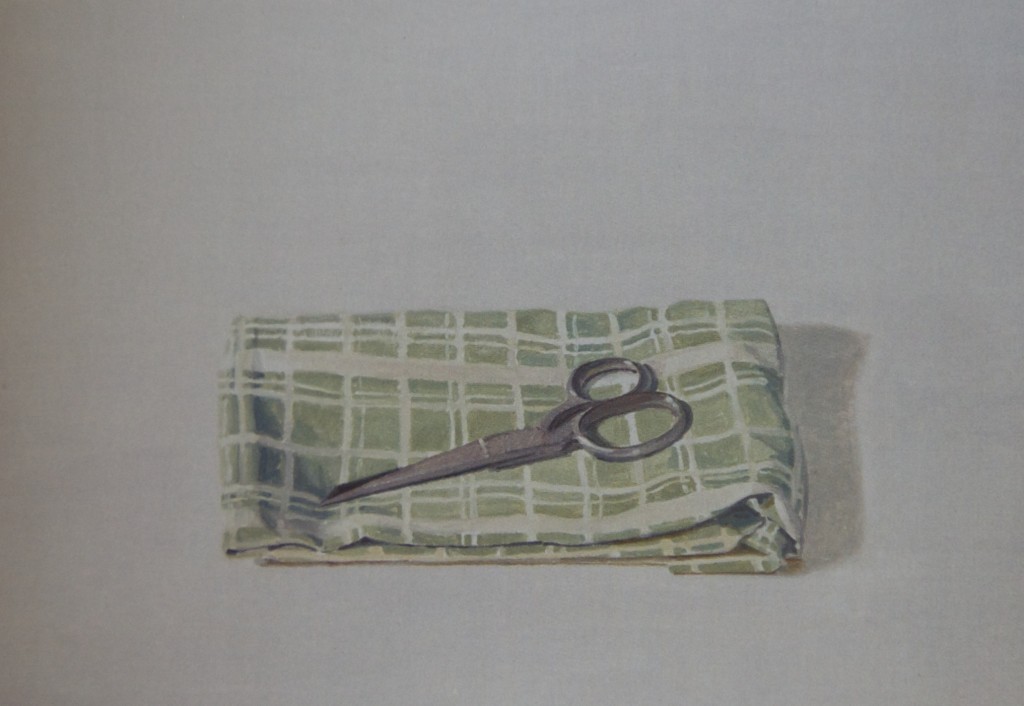

Scissors, Ron Milewicz, oil on linen

Spools, Ron Milewicz, oil on linen

I’ve never posted two paintings from a show I’ve written about, so that alone ought to indicate how much I liked this one. One of the deepest pleasures of my visit to Chelsea two weeks ago was seeing the quietly commanding still life paintings of Ron Milewicz at Elizabeth Harris. Having been given a free copy of the exhibition catalog, and reading the background on the show, entitled the soul exceeds its circumstances, I was conflicted, in a good way, about why the show worked so well. To say it “worked” is to diminish the subtle effect it has on you, at a purely instinctive and visual level. Even without knowing what inspired the show, you can feel these paintings are the outcome of restrained passion and love simply in the way he paints. You see image after image of modest household items, painted in an almost casual and un-assertive way, each object isolated in a field of white or Rembrandt-murk. The artist carefully depicts what he sees without fussing over hyper-realistic detail. These images immediately win you over with their humility, offered through an easy and relaxed execution. In painting after painting, you sense that Milewicz was working entirely within himself, as they say in sports, not striving to do anything more with the paint than he needed. Not trying to impress or dazzle with his skill; simply getting each object to the point where it’s all his own eye required to feel the life of the object. A brick, a shovel, a braid of challah bread, spools of thread, a hydrangea blossom, or a pair of scissors resting on a neatly folded cloth: they look as if they could smile back at you. Walking through the show, you feel as if you’re seeing tiny glimpses of the good life, in the highest sense, governed by an orderly middle-class serenity earned through hard work.

You might pause and wonder, as I did, why challah? Oh right, the artist is Jewish. Then, out of curiosity, you ask for a catalog and read the guest essay and the artist’s brief statement about his inspiration for the show. You realize this isn’t simply a refined way to make the simplest possible set of still lifes, but—looked at as a whole—this show is a fragmented narrative. These are glimpses of the happy life the artist’s grandfather led when he came to live in Brooklyn and work as a sample maker in Manhattan’s garment district. He and his wife apparently were gardeners as well. Yet you discover the deeper history behind each object when you read that Eli Milewicz weighed 60 pounds on the day Germany lost WWII and his “death march” to the Baltic Sea ended. His wife, Anna Kaplan, was also a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps. So you go back and look at each image and see the resonance of the horrific past in each painting: suddenly bricks mean a different sort of oven. A shovel is for digging both gardens and graves. Spools of thread struggle to breathe in their sealed plastic bags. And so on. If you are going to make a statement about anything, let alone something as evil as genocide, then it’s hard to imagine a more understated way to sum up an entire individual life in a set of images that have double, or triple, meanings. The show as a whole is a book of innocence and a book of experience, with both states of the soul fused together into half the images Blake required. And every one of these paintings is beautiful.

If art depends on commentary and knowledge extraneous to the image itself—and I generally hate it when that happens—then this is how it should be done. The paintings work well, entirely on their own, without background information, and yet they gain in gravity and, frankly, are even more interesting, when you hear why Milewicz was moved to paint such fraught images in such a sotto voce way. As Tom Sleigh puts it in the catalog essay: “The power of Milewicz’s images inheres in how he refuses to go in for the big teary-eyed gestures, and how ordinary objects like shovels, overcoats, and spools of thread are invested with deeper meanings. . . .but without insisting on them.” Those last five words are the key. The ‘deeper’ meaning is there if you wish to uncover it. Instruction isn’t included in the work itself, nor is it required. These are first and foremost paintings, not propositions. And very good ones at that.

October 6th, 2013 by dave dorsey

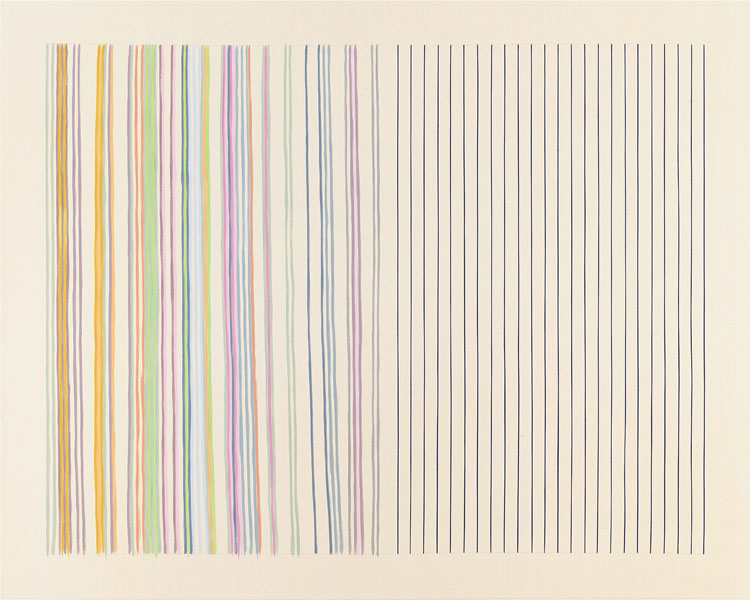

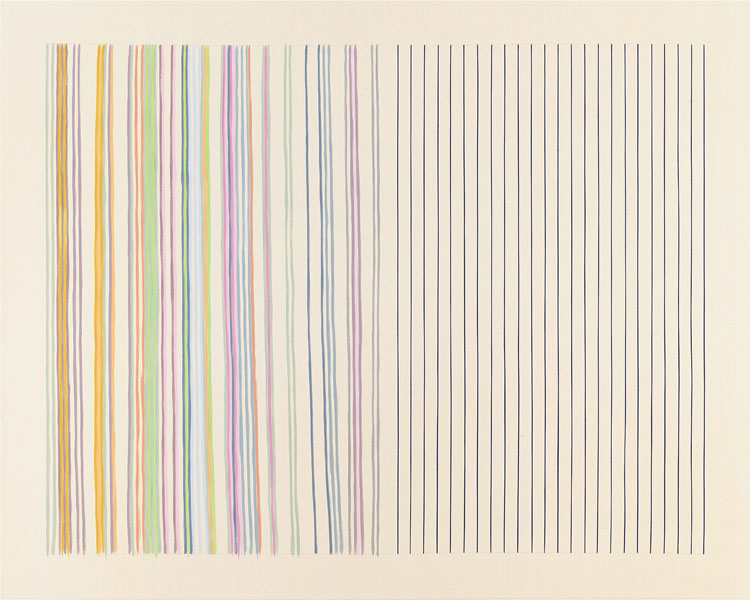

Mirror, Gene Davis, acrylic on canvas

After you’ve seen the more stident work of Ian Davenport at Kasmin–he drips orderly vertical stripes down aluminum and steel panels and then gets the paint to go all Dionysian on us near the bottom–walk a few blocks down to Ameringer McEnergy Yoho for something that looks at first quite similar but feels entirely different. Get up close to one of the Gene Davis canvases, and if you look intently enough you’ll see a perfectly straight pencil line just visible through some of the stripes. He used a straight-edge to establish where he wanted the stripes to go, but then painted them without any assistance other than his eye. The line was more of a suggestion than a rule, though most of the paintings don’t show how unsteadily his brush moved down the canvas until you really stand a few inches away. Math and human muscle are at odds in so many ways, but here it’s a good thing: minimalism seems friendly and humble and understated. I walked past these paintings on my way into the back room without paying much attention, but on the way out I stopped and tried to examine how he applied his paint, and it changed my attitude. A line of graphite, and then freehand. No masking tape for this guy. Suddenly, I started liking what I saw. It also helped, for some reason, to read this in the handout, though I really don’t quite understand it:

Look at a painting in terms of individual colors. In other words, instead of simply glancing at the work, select a specific color such as yellow or a lime green, and take the time to see how it operates across the painting. Approached this way, something happens, I can’t explain it. One must enter the painting through a single color.

–Gene Davis