Archive for July, 2014

July 31st, 2014 by dave dorsey

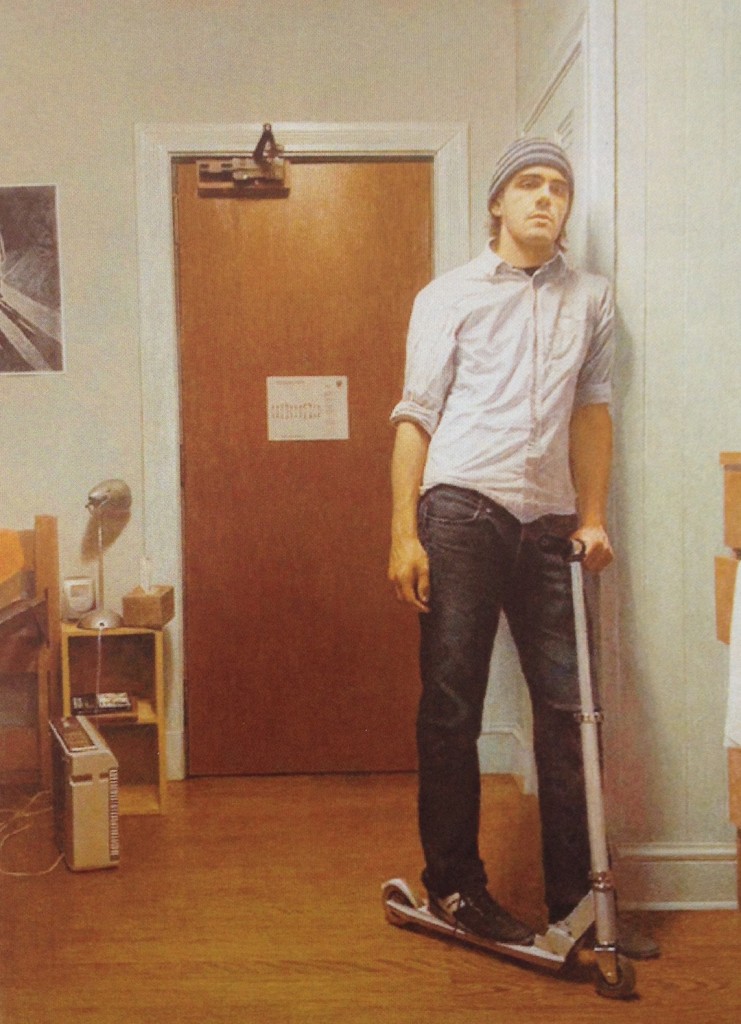

Miracles of Modern Science, John Younger, oil, 68″ x 48″

I was pleased to be included in the 78th Midyear Exhibition at the Butler Institute, and to have been awarded an Honorable Mention for Carpe Diem: Autumn’s Last Flowers, which was one of the works in my solo show at Viridian Artists this summer. The catalog for the show arrived today, and it was heartening to see so much great work in the exhibition. I made it into last year’s Midyear as well, yet the work in that show I found a little discouraging, though chalked it up to the fact that I was looking at thumbnail reproductions. This year, though, even at such a small scale, the bulk of the art looks great. There’s a marked emphasis on the human figure and portraiture, and some of my favorites in the show depict people set in unexpected settings, or presented in surprising ways, all rendered with amazing skill: Miracles of Modern Science, by John Younger, Brooklyn, by Marc Winnat, and Earth Angels, by Allan Charles Orr. It’s cheering to see so much representational art, many of them beautiful in a way that isn’t cloying. Plenty of abstract work got into the show. Even without the award, I was honored to be included.

July 27th, 2014 by dave dorsey

In that order? From today’s Book Review:

“Freud’s early works were strongly marked by Morris’s influence, with an exquisitely linear style, brittle and subtly exaggerated. What you remember about them — and they are mostly portraits — are the subjects’ wide, haunted eyes. One sitter later recalled how “he always started with an eyeball, then he imprisoned the eye and then an eyebrow, then a nostril.” Freud hadn’t much money in those days, but he never lacked for patrons or for opportunities to pursue his “violently closely held belief to carry on with lords and ladies,” as one of his daughters put it. He enjoyed the lowlife just as much. By the mid-’50s, though, his art dissatisfied him. “I was getting approval for something that wasn’t of great account,” he felt, and he found his way toward the more painterly, rather clotted and lugubrious style that made him rich and famous. Freud recalled how Kenneth Clark, the former director of the National Gallery, “wrote a card saying that I had deliberately suppressed everything that made my work remarkable . . . and ended, ‘I admire your courage.’ I never saw him again.”

Clark was fundamentally right, I think, and yet Freud remains a fascinating artistic oddity, his work unlike anyone else’s. This brief biography by Phoebe Hoban — the author of full-length lives of Alice Neel and Jean-Michel Basquiat — negotiates with equanimity a life that seems a disorderly maelstrom of sex, fighting, art, gambling, all obsessively pursued and so mixed up it’s sometimes hard to tell one from the other.”

July 26th, 2014 by dave dorsey

As a follow-up to my last post, a friend sent me this:

As a follow-up to my last post, a friend sent me this:

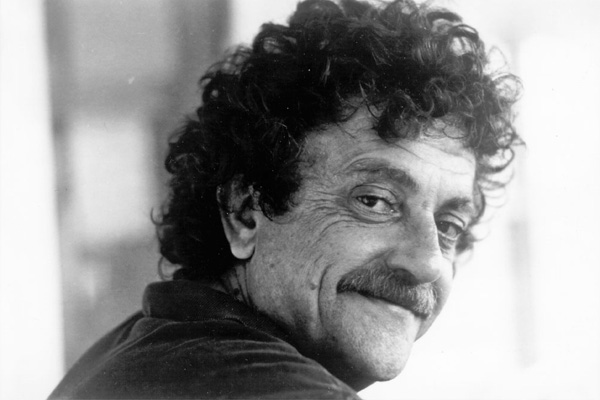

Kurt Vonnegut: “…my father, who struggled to become a painter after he was forced into early and unwelcome retirement by the Great Depression. He had reason to be optimistic about his new career, since the early stages of his pictures, whether still lifes or portraits or landscapes, were full of pow. Mother, meaning to be helpful, would say of each one: “That’s really wonderful, Kurt. Now all you have to do is finishit.” He would then ruin it.”

July 23rd, 2014 by dave dorsey

This is interesting, from Brain Pickings, a quote from a book on intuition, Answers for Aristotle:

Research on acquiring skills shows that, roughly speaking, and pretty much independently of whether we are talking about a physical activity or an intellectual one, people tend to go through three phases while they improve their performance. During the first phase, the beginner focuses her attention simply on understanding what it is that the task requires and on not making mistakes. In phase two, such conscious attention to the basics of the task is no longer needed, and the individual performs quasi-automatically and with reasonable proficiency. Then comes the difficult part. Most people get stuck in phase two: they can do whatever it is they set out to do decently, but stop short of the level of accomplishment that provides the self-gratification that makes one’s outlook significantly more positive or purchases the external validation that results in raises and promotions. Phase three often remains elusive because while the initial improvement was aided by switching control from conscious thought to intuition—as the task became automatic and faster—further improvement requires mindful attention to the areas where mistakes are still being made and intense focus to correct them. Referred to as ‘deliberate practice,’ this phase is quite distinct from mindless or playful practice.

This reminds me of a point in painting where the painting is good enough, or at least as good as one’s work has been up to this point in my life, and there’s a fork in the road: either you consider it finished or you keep investing time in the areas where it seems to fall short, upon close inspection, but in ways that only I would probably notice. That seems like a self-indulgent or risky investment of time, since it isn’t clear that more work will make the painting more effective in the eyes of anyone else. Knowing what’s “good enough” is, in fact, part of what makes certain quickly executed paintings great. They do their work so economically that more effort would drain the life out of the marks already applied to the surface. I find myself at that fork in the road while doing a lot of paintings now. This passage from Answers for Aristotle also seems to point toward a period of mastery when you realize you can reliably do whatever you have chosen to do, up to that point in your painting life, but then you find yourself asking the question “This is what I can do. What it is I most deeply want to do with all these acquired skills?”

July 21st, 2014 by dave dorsey

Wallace Shawn

“I have an enormous appetite to see life as I know it presented in front of my eyes.

That seems strange—after all, why don’t I just walk out into the street? But the thing is that you can’t really look at things out in the street, much less in your own apartment or in your friends’ apartments. You can look in the theater in a completely different way from the way you can look in life. You’re allowed to really look at a play—even stare.

In life, you are a character in the scene. When you’re a character in the scene, you can’t really look at the scene. If someone’s talking to you, you must respond appropriately. You can’t just stare at the person. You can’t look at life with the degree of attention and focus that you can employ when you look at a play, because you have to participate. And the people you’re staring at would find it rude. But if you’re sitting in an audience watching a scene, you can focus your entire being on looking at that scene. It’s a very special privilege.

In . . . Les Éphémères, they had a scene where a fisherman and his wife and some other people have taken their children on an outing, and they come home, and they put the kids to bed. The kids are already asleep—they’re very young children—and they carry them in asleep, and they put them to bed. It takes probably fifteen minutes, or at least ten. No talking. Now, I have very little interest in family life, in children, et cetera. If you said, We’re now going to do a ten-minute scene about putting children to bed, I would be bored before you even finished the sentence. But it was so true and so real and so interesting. It was beautiful, and I was moved by it.”

–Wallace Shawn, The Paris Review

July 19th, 2014 by dave dorsey

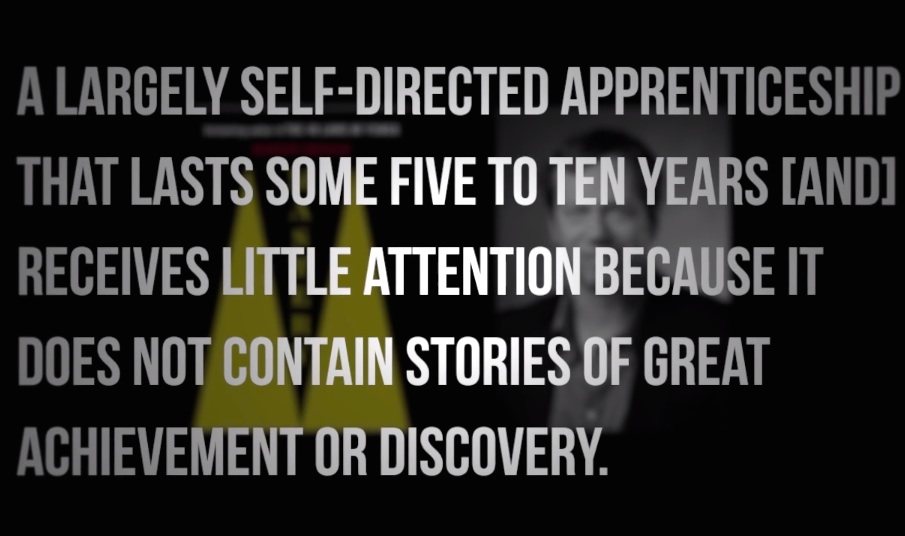

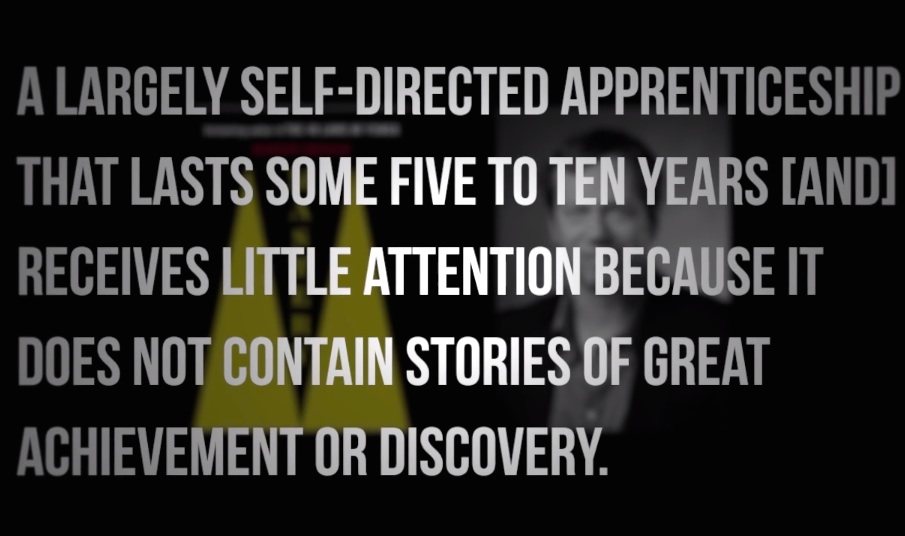

Great short video on working in obscurity. Leonardo: fail, fail, fail, fail, fail . . . success. “John Coltrane practiced the saxophone feverishly every single day for seventeen years before he got his first big hit . . . ” A previous video shows you a whole rogue’s gallery of losers in their twenties who eventually quit losing. “Leonardo got his big break when he was 46.”

Great short video on working in obscurity. Leonardo: fail, fail, fail, fail, fail . . . success. “John Coltrane practiced the saxophone feverishly every single day for seventeen years before he got his first big hit . . . ” A previous video shows you a whole rogue’s gallery of losers in their twenties who eventually quit losing. “Leonardo got his big break when he was 46.”

July 17th, 2014 by dave dorsey

“Works of art . . . (create) about them a confluence of simple hearts, a community united not in what they are . . . but in the collective mystery of what they are not and now find embodied before them. Unfortunately, the democracy of simple hearts is founded on the dangerous assumption that gorgeous parrots, hewn from what we lack . . . will continue to make themselves visible and available to us. But this is not necessarily so. Flaubert is dead, and the disciplines of desire have lost their urgency in the grand salons of comfort and privilege we have created for the arts. The self-congratulatory rhetoric of sensibilite continues to perpetuate itself, and in place of gorgeous parrots, we now content ourselves with the ghostly successors of Marie Antoinette’s peasant village, tastefully installed within the walls of Versailles.”

“Works of art . . . (create) about them a confluence of simple hearts, a community united not in what they are . . . but in the collective mystery of what they are not and now find embodied before them. Unfortunately, the democracy of simple hearts is founded on the dangerous assumption that gorgeous parrots, hewn from what we lack . . . will continue to make themselves visible and available to us. But this is not necessarily so. Flaubert is dead, and the disciplines of desire have lost their urgency in the grand salons of comfort and privilege we have created for the arts. The self-congratulatory rhetoric of sensibilite continues to perpetuate itself, and in place of gorgeous parrots, we now content ourselves with the ghostly successors of Marie Antoinette’s peasant village, tastefully installed within the walls of Versailles.”

–Dave Hickey, Air Guitar, “Simple Hearts”

July 15th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Cozy/Rainy Day, Davis Cone, acrylic on canvas

July 13th, 2014 by dave dorsey

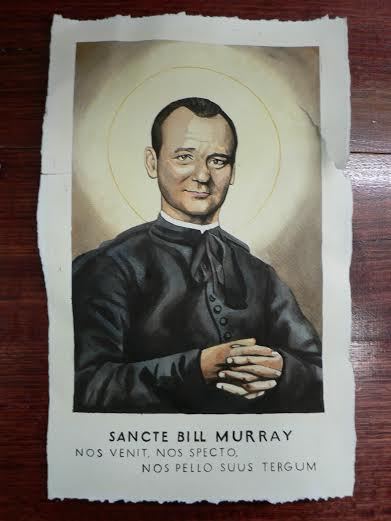

Saint Bill

Submissions until July 21 for the all-Bill Murray exhibition at Public Works in San Francisco. It could be so much better than much of what appears here. Opens Aug. 8.

July 10th, 2014 by dave dorsey

From Esquire:

From Esquire:

SS: It’s at the center of everything, this idea of narrative and stories. So I am always thinking about it: Is there another way to do it? That’s why I was so fascinated and obsessed with the cave paintings in France. I’m like, “Fuck, there it is. The first stories.” I draw a little bit and was like, “Somebody practiced those.” 30,000 years ago you have your forehead out to here, you don’t just pick up a piece of charcoal and do that. That was something that struck me as “Where’s the practice board?” The other thing that I’m interested in, which is tangential, but not unrelated… All art to me is about problem solving. So I’m obsessed with problem solving. Somewhere someone discovered something or somebody was tasked to figure something out and they did. What did they figure out and how? One of the things that I believe is true is the art model of problem solving is incredibly efficient because ideology has no place there. There’s only the thing and what the thing needs to be. When I look around the world and think why is everything working or not working, it’s because it’s entrenched ideology. You can’t solve a problem if you’re sitting down with people who say, “All these ideas are off the table because of what I believe.”

July 1st, 2014 by dave dorsey

Matthew Barney

I saw all of The Cremaster Cycle at the Guggenheim when the show was up . . . God, was it that long ago? My response was something like Bill Murray’s in Tootsie while he was watching the soap opera: “That is one nutty hospital.” My only reservation by the end of the five feature-length films was that I still didn’t know what the eye at the top of the pyramid on the back of a dollar bill is looking at, though I admired Barney’s attempt to cover just about everything else in human life. The rest of the exhibition taught me what the word vitrine means though I’ll probably never have a chance to use that word after this post. So far I’ve taken a pass on “River of Fundament,” a title that makes me smile, as I’m sure it’s meant to, though I really did admire Barney’s filthy Irish energy the first time around. Plus, like me, he grew up in Idaho, so I have to root for him. But being on Barney’s side is like putting money on the New England Patriots, isn’t it? (Go Bills!) This amused me:

“We hear about Matthew Barney’s six-hour film of Norman Mailer’s seven-hundred-page Ancient Evenings, an unwatchable adapation of an unreadable book, and we think, Hey that might be great! It’s the American way.”

—Adam Gopnik, “Go Giants”, The New Yorker, April 21, 20145

(I’m off to attend my son’s wedding in Mexico for the rest of the week, if we can trust United to get us there. We missed our originating flight this morning, which is why I was catching up on Gopnik.)