December 15th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Story, Richard Maury, oil on canvas mounted on panel, 21″ x 27 1/2″

Photography of a certain sort—with a shallow depth of field—mimics the way the human eye sees more accurately than an image where everything is equally defined and sharp. What I see when I steady my gaze is actually a very tiny fragment of what’s before me. Right now it’s little more than three words on a computer screen around which everything else hovers, softly indistinct. What’s in sharp focus occupies about a square foot, right at the center, of what’s in view. At TV-distance, maybe three square feet of my entire field of vision are crisply defined. Which, conveniently, is roughly the size of the TV screen. The rest of what’s out there, around the periphery of that target area, remains indistinct. I forget this is the case because my eye is about as mobile and busy as a fly trapped in a room. Unless I’m watching something on that TV, or on my computer, my eye never rests. The sense that I see an entire room in great detail, with clarity, represents a mix of working memory and imagination, my mind constantly assembling and unifying the view. What I see is at any point during the day is, ipso facto, a work of imagination.

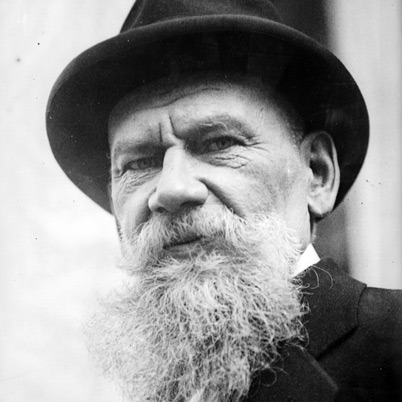

This was my thinking recently when I resolved to finish eight or nine small, quick still lifes (photo-realistic in the sense that they will be sourced from photographs with a shallow depth of field where much of what’s shown is out of focus). At about the same time as I decided to try this, Tom Insalaco happened to show me a catalog of Richard Maury’s exhibit at Forum Gallery in 2001. Which, of course, immediately pulled me in exactly the opposite direction: to continue painting images where everything is crisply rendered, as I’ve mostly done. I was fascinated by the still life Tom singled out, showing a few common objects illuminated by natural light presumably through one of his Italian home’s old casement windows. So, when I got home, I found what I suspected was the same catalog from a third-party seller on Amazon, and I ordered it. It arrived a couple days later, and, having studied it for a while, I’m humbled by Maury’s work.

I assume the catalog represents all of the work he completed from 1996-2001, as Robert Fishko suggests in his introduction. It isn’t surprising that he praises Maury so effusively. It wouldn’t faze me if you told me each of these fifteen paintings required a year to complete, yet Maury apparently dispatched them at the rate of about three per year, which is staggering given the level of exactitude.

On the cover, in his self-portrait, everything revolves around his MORE

December 13th, 2015 by dave dorsey

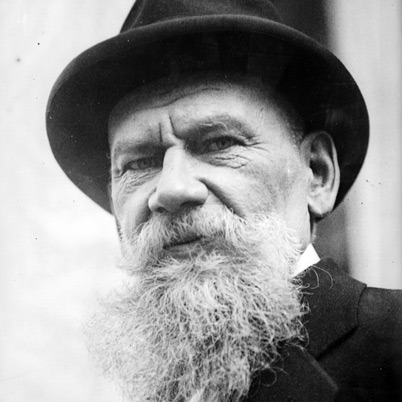

A real work of art can only arise in the soul of an artist occasionally, as the fruit of the life he has lived, just as a child is conceived by its mother. But counterfeit art is produced by artisans and handicraftsmen continually, if only consumers can be found.

That’s a quote from Leo Tolstoy’s What Is Art? Works for me. Like Knausgaard’s attentive account of how he responds to art from different periods, looking at art history from the basis of how it makes him feel—and using that as a basis for assessing whether or not the work actually accomplishes anything—Tolstoy says what strikes me as incredibly obvious and utterly subversive, as Knausgaard is. He expressed (suppressed) truths about all creative activity over the past century or so, in a way that seems undeniable, but problematic. (By art, he means it in the broadest sense, as in “the arts:” poetry, fiction, drama, music, visual art.) If he’s right, then even Shakespeare was bullying us with his Elizabethan vocabulary into a submission to art that reeks of obscurity and privilege, wealth, class divisions, and superiority. My problem is that I love modernism, and I think Shakespeare continues to be the greatest writer who ever lived, and yet Tolstoy was prophetic. Can two contradictory views both be valuable? The book also links art and religion, and religion seems to be popping up constantly in this blog, maybe because I think art and religion are on the same quest, groping in the dark for a moment of illumination about what’s real and true. (Both Wittgenstein, who was essentially a follower of Tolstoy, in his personal life, and Gerhard Richter, refer to their pursuits as “religious.”) “Upper-class art” is, for Tolstoy, simply a generic term for art in his time: the equation of art and “upper-class art” has never been more trenchant than it is now for describing the so much visual art that gets shown, discussed, and bought for the highest sums.

You can read What is Art? for free on the Web. Here are the passages I highlighted years ago in a photocopy of it. They have gotten more and more trenchant as time passes. This is a condensation of passages from page 147 to the end of the book:

For the great majority of working people, our art, besides being inaccessible on account of its costliness, is strange in its very nature, transmitting as it does the feelings of people far removed from those conditions of laborious life, which are natural to the great body of humanity. That which is enjoyment to a man of the rich classes, is incomprehensible, as a pleasure, to a working man, and evokes in him either no feeling at all, or only a feeling quite contrary to that which it evokes in an idle and satiated man.

To thoughtful and sincere people there can therefore be no doubt that the art of our upper-classes never can be the art of the whole people. But if art is an important matter, a spiritual blessing, essential for all men (“like religion,” as the devotees of art are fond of paying), then it should be accessible to everyone. And if, as in our day, it is not accessible to all men, then one of two things (are true): either art is not the vital matter it is represented to be, or that art which we call art is not the real thing.

The first great result was that art was deprived of the infinite, varied, and profound religious subject-matter proper to it. The second result was that having only a small circle of people in view, it lost its beauty of form and became affected and obscure; and the third and chief result was that it ceased to be either natural or even sincere, and became thoroughly artificial and brain-spun.

The impoverishment of the subject-matter of upper-class art was further increased by the fact that, ceasing to be religious, it ceased also to be popular, and this again diminished the range of feelings which it transmitted. For the range of feelings experienced by the powerful and the rich, who have no experience of labor for the support of life, is far poorer, more limited, and more insignificant than the range of feelings natural to working people.

We think the feelings experienced by people of our day and our class are very important and varied; but in reality almost all the feelings of people of our class amount to but three very insignificant and simple feelings: the feeling of pride, the feeling of sexual desire, and the feeling of weariness of life. These three feelings, with their outgrowths, form almost the only subject-matter of the art of the rich classes.

It has come, finally, to this: that not only is haziness, mysteriousness, obscurity, and exclusiveness (shutting out the masses) elevated to the rank of a merit and condition of poetic art, but even incorrectness, indefiniteness, and lack of eloquence are held in esteem.

The fact that I am accustomed to a certain exclusive art, and can understand it, but am unable to understand another still more exclusive art, does not give me a right to conclude that my art is the real true art, and that the other one, which I do not understand, is an unreal, a bad art. I can only conclude that art, becoming ever more and more exclusive, has become more and more incomprehensible to an ever-increasing number of people, and that, in this progress towards greater and greater incomprehensibility (on one level of which I am standing, with the art familiar to me), it has reached a point where it is understood by a very small number of the elect, and the number of these chosen people is ever becoming smaller and smaller.

The assertion that art may be good art, and at the same time incomprehensible to a great number of people, is extremely unjust, and its consequences are ruinous to art itself; but at the same time it is so common and has so eaten into our conceptions, that it is impossible sufficiently to elucidate all the absurdity of it.

We are quite used to such assertions, and yet to say that a work of art is good, but incomprehensible to the majority of men, is the same as saying of some kind of food that it is very good but that most people can t eat it.

Moreover, it cannot be said that the majority of people lack the taste to esteem the highest works of art. The majority always have understood, and still understand, what we also recognize as being the very best art: the epic of Genesis, the Gospel parables, folk-legends, fairy-tales, and folk-songs are understood by all. How can it be that the majority has suddenly lost its capacity to understand what is high in our art?

Great works of art are great only because they are accessible and comprehensible to every one.

The direction art has taken may be compared to placing on a large circle other circles, smaller and smaller, until a cone is formed, the apex of which is no longer al circle at all. That is what has happened to the art of our times.

This has resulted from the following causes. Universal art arises only when some one of the people, having experienced a strong emotion, feels the necessity of transmitting it to others. The art of the rich classes, on the other hand, arises not from the artist’s inner impulse, but chiefly because people of the upper classes demand amusement and pay well for it. They demand from art the transmission of feelings that please them, and this demand artists try to meet. But it is a very difficult task, for people of the wealthy classes, spending their lives in idleness and luxury, desire to be continually diverted by art; and art, even the lowest, cannot be produced at will, but has to generate spontaneously in the artist’s inner self.

Equally little can imitation, realism, serve, as many people think, as a measure of the quality of art. Imitation cannot be such a measure, for the chief characteristic of art is the infection of others with the feelings the artist has experienced, and infection with a feeling is not only not identical with description of the accessories of what is transmitted, but is usually hindered by superfluous details. The attention of the receiver of the artistic impression is diverted by all these well-observed details, and they hinder the transmission of feeling even when it exists.

In our society three conditions co-operate to cause the production of objects of counterfeit art. They are:

- The considerable remuneration of artists for their productions and the professionalization of artists, which this has produced.

- Art criticism.

- Schools of art.

While art was as yet undivided, and only religious art was valued and rewarded while indiscriminate art was left unrewarded, there were no counterfeits of art, or, if any existed, being exposed to the criticism of the whole people, they quickly disappeared. But as soon as that division occurred, and the upper classes acclaimed every kind of art as good if only it afforded them pleasure, and began to reward such art more highly than any other social activity, immediately a large number of people devoted themselves to this activity, and art assumed quite a different character and became a profession. And as soon as this occurred, the chief and most precious quality of art its sincerity was at once greatly weakened and eventually quite destroyed.

Infection is only obtained when an artist finds those infinitely minute degrees of which a work of art consists, and only to the extent to which he finds them. And it is quite impossible to teach people by external means to find these minute degrees: they can only be found when a man yields to his feeling. No instruction can make a dancer catch just the tact of the music, or a singer or a fiddler take exactly the infinitely minute centre of his note, or a sketcher draw of all possible lines the only right one, or a poet find the only meet arrangement of the only suitable words. All this is found only by feeling. And therefore schools may teach what is necessary in order to produce something resembling art, but not art itself. The teaching of the schools stops there where the wee bit begins consequently where art begins. Accustoming people to something resembling art, disaccustoms them to the comprehension of real art. And that is how it comes about that none are more dull to art than those who have passed through the professional schools and been most successful in them. Professional schools produce an hypocrisy of art precisely akin to that hypocrisy of religion which is produced by theological colleges for training priests, pastors, and religious teachers generally. As it is impossible in a school to train a man so as to make a religious teacher of him, so it is impossible to teach a man how to become an artist.

These three conditions the professionalization of artists, art criticism, and art schools have had this effect: that most people in our times are quite unable even to under stand what art is, and accept as art the grossest counterfeits of it.

I have little hope that what I adduce as to the perversion of art and taste in our society will be accepted or even seriously considered. Nevertheless, I must state fully the inevitable conclusion to which my investigation into the question of art has brought me. This investigation has brought me to the conviction that almost all that our society considers to be art, good art, and the whole of art, far from being real and good art, and the whole of art, is not even art at all, but only a counterfeit of it.

The difficulty of recognizing real works of art is further increased by the fact that the external quality of the work in false productions is not only no worse, but often better, than in real ones; the counterfeit is often more effective than the real, and its subject more interesting.

The animal unerringly finds what he needs. So also the man, if only his natural qualities have not been perverted, will, without fail, select from among thousands of objects the real work of art he requires that infecting him with the feeling experienced by the artist.

All these people, with very few exceptions, artists, and public, and critics, have never (except in childhood and earliest youth, before hearing any discussions on art), experienced that simple feeling familiar to the plainest man and even to a child, that sense of infection with another’s feeling, compelling us to joy in another’s gladness, to sorrow at another’s grief, and to mingle souls with another, which is the very essence of art. And therefore these people not only cannot distinguish true works of art from counterfeits, but continually mistake for real art the worst and most artificial, while they do not even perceive works of real art, because the counterfeits are always more ornate, while true art is modest.

There is one indubitable indication distinguishing real art from its counterfeit, namely, the infectiousness of art. If a man, without exercising effort and without altering his standpoint, on reading, hearing, or seeing another man s work, experiences a mental condition which unites him with that man and with other people who also partake of that work of art, then the object evoking that condition is a work of art. And however poetical, realistic, or interesting a work may be, it is not a work of art if it does not evoke that feeling (quite distinct from all other feelings) of joy, and of spiritual union with another (the author) and with others (those who are also infected by it).

If a man is infected by the author’s condition of soul, if he feels this emotion and this union with others, then the object which has effected this is art; but if there be no such infection, if there be not this union with the author and with others who are moved by the same work then it is not art. And not only is infection a sure sign of art, but the degree of infectiousness is also the sole measure of excellence in art.

I have mentioned three conditions of contagiousness in art, but they may all be summed up into one, the last, sincerity, i.e. that the artist should be impelled by an inner need to express his feeling.

It is always complied with in peasant art, and this explains why such art always acts so powerfully; but it is a condition almost entirely absent from our upper-class art, which is continually produced by artists actuated by personal aims of covetousness or vanity. Such are the three conditions which divide art from its counterfeits, and which also decide the quality of every work of art apart from its subject-matter. If the work does not transmit the artist peculiarity of feeling, and is therefore not individual, if it is unintelligibly expressed, or if it has not proceeded from the author’s inner need for expression it is not a work of art. If all these conditions are present, even in the smallest degree, then the work, even if a weak one, is yet a work of art.

A real work of art can only arise in the soul of an artist occasionally, as the fruit of the life he has lived, just as a child is conceived by its mother. But counterfeit art is produced by artisans and handicraftsmen continually, if only consumers can be found.

Art will become accessible to the whole people, because, in the first place, in the art of the future, not only will that complex technique, which deforms the productions of the art of to-day and requires so great an effort and expenditure of time, not be demanded, but, on the contrary, the demand will be for clearness, simplicity, and brevity . . .

And therefore security of maintenance is a condition most harmful to an artist s true productiveness, since it removes him from the condition natural to all men, that of struggle with nature for the maintenance of both his own life and that of others, and thus deprives him of opportunity and possibility to experience the most important and natural feelings of man. There is no position more injurious to an artist’s productiveness than that position of complete security and luxury in which artists usually live in our society. The artist of the future will live the common life of man, earning his subsistence by some kind of labor. The fruits of that highest spiritual strength which passes through him he will try to share with the greatest possible number of people, for in such transmission to others of the feelings that have arisen in him he will find his happiness and his reward. The artist of the future will be unable to understand how an artist, whose chief delight is in the wide diffusion of his works, could give them only in exchange for a certain payment.

And indeed, for the artists of our society and day, it is impossible, but not for the future artist, who will be free from all the perversion of technical improvements hiding the absence of subject-matter, and who, not being a professional artist and receiving no payment for his activity, will only produce art when he feels impelled to do so by an irresistible inner impulse. The art of the future will thus be completely distinct, both in subject-matter and in form, from what is now called art. The only subject-matter of the art of the future will be either feelings drawing men towards union, or such as already unite them; and the forms of art will be such as will be open to everyone. And therefore, the ideal of excellence in the future will not be the exclusiveness of feeling, accessible only to some, but, on the contrary, its universality. And not bulkiness, obscurity, and complexity of form, as is now esteemed, but, on the contrary, brevity, clearness, and simplicity of expression.

December 11th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Karl Ove Knausgaard

After about two hundred pages, My Struggle, Book 1, by Karl Ove Knausgaard, abruptly shifts into a higher gear as a brief account of his falling in love as a teen with a girl named Hanna serves as a threshold for him to leap into the future, much closer to the present, and describe his life as a writer and expectant father in Stockholm. His indebtedness to Proust becomes even more evident than it already has been in the way he drifts from narrative to essay–the book begins with a startling, riveting account of what we do with the bodies of the dead, how we hide them immediately and inexplicably keep them close to the ground. It’s a phenomenological examination of our collective denial of mortality–the oddity of our rituals around it as an avoidance of the unknowable. Here, two hundred pages later, he launches into a meditation on visual art which, at the end, comes full circle, halfway through the book, finally, with those opening Montaigne-like observations about mortality. He isn’t just talking about death here, but about consciousness itself. “The intellect has taken over everything.” He points to the unreality of the world we inhabit now, and is trying to show how we’ve increasingly transformed our world into a virtual, intellectual shadow-play where ideas and concepts replace the actual phenomena of experience, and within all of this is embedded a critique of art since Manet. What he says here reflects my reactions in London when I walked through the Tate, which I loved, compared to the Tate Modern, which left me not only cold, but feeling a surprising aversion for a lot of what I saw there, even though I love so much art from the past century. Something about the place itself seemed almost inhuman and repellent. It was like the divide between reason and feeling Knausgaard outlines in his reaction to visual art: feeling increasingly has no place in creative work devoted to concepts, irony, theory, and analysis. His extreme reaction to certain paintings is almost comical, but he isn’t trying to be funny; for him it’s like finding water in a desert:

“. . . . a book about Constable I had just bought. Mostly oil sketches, studies of clouds, countryside, sea. I didn’t need to do any more than let my eyes skim over them before I was moved to tears. So great was MORE

December 8th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Spring Landscape, Fairfield Porter

“On the school playground that lay squashed between two blocks of flats twenty meters up from my office the shouts of children suddenly fell quiet, it was only now that I noticed. The bell had rung. The sounds here were new and unfamiliar to me, the same was true of the rhythm in which they surfaced, but I would soon get used to them, to such an extent that they would fade into the background again. You know too little, and it doesn’t exist. You know too much, and it doesn’t exist. Writing is drawing the essence of what we know out of the shadows. That is what writing is about. Not what happens there, not what actions are played out there, but the there itself. There, that is writing’s location and aim. But how to get there?”

–Karl Ove Knausgaard, My Struggle, Book 1

Though I take exception to that word “know,” this is a brilliant little passage, in the way his perspective snaps outward to encompass everything. Knausgaard begins with what we’ve all experienced: you are either too far from the sound of children playing to hear them or you are so close, in a sustained way, hour after hour and day after day, that you cease to hear them because they have become mere white noise. They have become the backdrop you forget as you watch and listen to what’s going on in the little spotlight of attention your mind sheds on whatever place you’re in. Knausgaard moves immediately, with a little metaphoric step, to a slightly different point about conscious awareness in general: the “there” of the world is so unceasing that we become oblivious to everything in our environment, and in ourselves, other than the little novelties of our daily experience. Too little or too much of the children laughing, and you cease to hear them. The world as a whole is far too much with us. It just is, and you are the world you’re in–you can’t step away from it and get a comprehensive look at it, as you could some space you occupy. You are it. You would have to be able to step out of yourself. Constantly, the “there” of your world disappears, and remains out of reach, unrecognized, if not for art, or meditation, or the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea, or a song that became your daily world twenty or thirty years ago and was forgotten until you heard it again just now. And suddenly you behold the “there” of that world, from back then, for the first time.

In a dozen posts, so far, and in dozens more, no doubt, this is something I’ve been getting at, though in the context of painting, rather than MORE

December 5th, 2015 by dave dorsey

@guywithtie on Instagram

This gushing account of how Instagram is disrupting the supply chain of fine art cracked me up, it sounded so over-the-top. In due time, I’m going to devote my Instagram mostly to my painting, and I’ll report on whether or not His Serene Highness Pierre d’Arenberg will allow my paintings to dry before he sends me his credit card number for the overnight shipping. I guess I’m expecting something a little less hectic than the feeding frenzy offered here by Vogue:

The social media platform is not only launching the career of under-the-radar artists, it is providing the world with an entirely new way to access art. Where artists once had to first get support of the art world elite—critics, galleries and big name collectors, which would eventually lead to museum shows—before reaching the monied masses, today artists use Instagram as their own virtual art gallery, playing both dealer and curator while their fans become critics and collectors, witnessing the creative process in real time.

“I can post a painting and it will sell before the paint is dry,” explained artist Ashley Longshore,whose glossy crystal-covered canvases are regularly bought straight off her Instagram feed for upwards of $30,000. The 37-year-old is based in New Orleans but will often ship her artworks directly from her Uptown studio to London, Tokyo, and Switzerland, where she recently sold a painting to His Serene Highness Pierre d’Arenberg for an undisclosed amount. “My collectors will text and email me their credit card details, they mail checks; it is literally a frenzy to see who can whip out their AmEx first!” admits Longshore, whose nearly 2,000 Instagram followers, and subsequent clients, include the likes of Blake Lively, the former President of Time Inc. Digital, Fran Hauser, and “one of the wives” of the Rolling Stones. “Technology is the platform of my business: All I need is my iPad, my Instagram and a delivery truck to haul all of this gorgeousness to the new homes where they will hang.”

“Like many technology disruptions, it levels the playing field,” says Kenneth Schlenker, the CEO and cofounder of Gertrude.co, a recently launched online platform where New Yorkers can sign up for modern-day art salons that bring collectors and the curious together to learn about, discuss and buy contemporary art in informal settings. “It used to be impossible for an artist to reach a massive audience directly,” he said, adding that “what is happening to art is comparable to what happened to music: The cards have been reshuffled.” Musicians don’t necessarily need record companies to distribute their work anymore—anyone can put an mp3 up on SoundCloud or video on YouTube and reach millions. Similarly, Schlenker says, Instagram gives artists the ability to control the way their story is told, and find people who want to hear it.

You know, these days, it can be hard to get real gorgeousness for only $30,000. No wonder it’s flying off the easel.

The comparison to music is a good one, and the Internet has allowed creators to eliminate middlemen left and right, yet the consumer/connoisseur is desperate to replace them. I don’t go searching for new music by scrolling through sites where unknowns post work: I listen to critics play me a sample of what they like, which is about as old school as it gets, except for the fact that I’m downloading podcasts to hear them: Sound Opinions, All Songs Considered. Maybe Instagram is different, but if all artists get a handle and start posting, how is anyone going to sort it all out, except by accidentally stumbling onto something good?

MORE