January 26th, 2016 by dave dorsey

John Sabraw, “Axioma VII” (2015), mixed media on wood panel, 12 x 12 inches (McCormick Gallery)

John Sabraw applies his alchemy to sludge, turning it into art by extracting pigment from it and then creating images of nature, under siege, autumnal, and weirdly beautiful. Turning poison into paint becomes a modern version of creating gold from lead. It isn’t just symbolic but a way to make cleanup a potentially profit-generating industry. An example of his recent work is on view at Manifest’s Secret Garden exhibition right now. Last year, Hyperallergic did an appreciative story on his use of toxic runoff to create pigments and offered examples of the finished work, as impressive as everything he’s done in the past. From Hyperallergic:

You can see the process in detail in a short documentary by Jacob Koestler, but in essence, the team takes samples from the most polluted areas, neutralizes the pH, then separates the concentrated iron from the clean water. As Kalliopi Monoyios reported for Scientific American last month, one goal of the project is to see if there’s a way that remediation could pay for itself through a sustainable product. Iron oxide pigments include familiar names like ochre, sienna, and umber, whose use dates back tens of thousands of years. In theory, production of pigments from the toxic sludge on a large scale could be marketable and support the removal of the pollutants as its own industry.

January 23rd, 2016 by dave dorsey

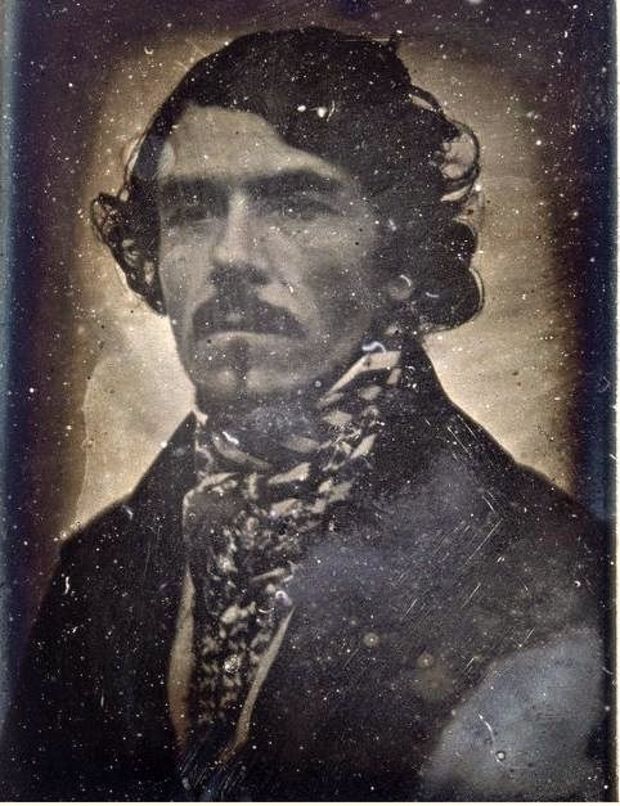

Adam Gopnik

Last month, Adam Gopnik, a regular writer for The New Yorker, drew an unusual connection between art criticism and religion in this conversation with Krista Tippett who hosts the On Being podcast. Before he got to that, he offered interesting thoughts on how he can be a devoted Darwinist and still take his Jewish faith seriously, as well as a husband who appreciates his wife’s Christianity. He named his children Darwin and Auden (after the poet, who was a Christian.) I’ve been bringing religion into this blog fairly often lately, against my better judgement, since it’s such a politicized topic now. I think painting and religious faith are close siblings. Schools of art, or fixed theories about what art needs to be, are maybe a bit more like organized religions. I’ll leave it to you, and maybe Kierkegaard, to separate the good from the bad in those last two sentences. (Jim Mott and I talk about this quite a bit, which reminds me that I still have to write about my conversation with him.) I see a parallel between art and faith partly because of the way both try to point toward the whole of human experience. Art does it with a quiet, indoor voice–at least the art I love. In contrast to organized religion, which seems to make a lot of noise now, genuine faith more often than not withdraws into silence. Art and faith attempt to draw attention to the entirety of life, the whole of things. How art does this is something only Proust and Samuel Beckett, of all people, offer suggestions that make sense to me, in a tentative way, but that’s for another post. The point is to trigger in the practitioner an imaginative and felt apprehension of the totality of life. For me painting at its best offers a certain kind of attention, a level of awareness, that combines gratitude, joy, affirmation, and a sort of impartial honoring of things as they are. The spirit of painting for me is: “before it’s gone, take a look at how amazing this apple is!” Painting is akin to meditation or prayer: a way of strenuously attempting to see what’s there in front of you, and inside you, as clearly as possible, without distortion. (Would that describe phenomenology as well?) And in both there’s a constant element of self-doubt, a questioning of whether or not what you’re seeing, and doing, is true or real or right or even just worthwhile.

All of this represents, in a different sphere, the striving at the heart of most faiths, especially the element of self-doubt. In contrast to how many people think faith means certainty, including a lot of believers. But to get back to Gopnik (who didn’t talk about any of this) he makes a point that art criticism, not art itself, is a practice before it’s a dogma–he got there by talking first about Darwin and religion. I think that distinction between practice and dogma works much better for art itself than for art criticism. Art is a practice that tends to spin off fixed principles, and schools, and prejudices against this or that in favor of that or this (the way faith splits up into antagonistic sects) but primarily it’s a non-conceptual way to see into the nature of things. Learning how to paint is learning how to be aware. It isn’t an activity that springs from conceptual origins (at least not the kind of painting I practice.) Instead of illustrating ideas, painting tries to show life–and show it in terms that can’t be translated into words or concepts and maybe, to some individual degree, in ways that haven’t been seen before. Dogma and ideas are beside the point. Practice is everything. Doing, not thinking.

This distinction between practice and dogma links back to religion. It’s the pivotal distinction of Karen Armstrong’s recent writing about God. She talks about how religion and faith are learned behaviors, ways of being in the world, that can’t be reduced to dogma, and have very little to do with the various “beliefs” which can be asserted as propositions about the world. Art integrates human experience though learned skills. Art doesn’t assert propositions. Faith works in the same way. What’s incredible about a great painting is that, rising up out of long practice, long learning of skills, you might get work that resonates with a sense of the whole of life and conveys what is true and good–as the artist strives to adhere to those things in something as simple as the way she applies her paint. All of these things are equally true, in a slightly different and more important way, for the discipline of a Buddhist, Hindu, Jew, Muslim, or Christian. The goal is the same: to act in harmony with what’s real and true, through years of practice. The hope is to create an extremely humble, living relationship with the world beyond your head, as Matthew Crawford puts it, while being acutely aware of how difficult it is for your mind to remain aware of its own severe limitations and its default setting for despair, cynicism, and doubt.

Here is a sample of Gopnik’s comments. I’m puzzled by the genealogy he rattles off–I think I would reorder the isms a bit. Surrealism begat abstract expressionism didn’t it? But he makes his point:

Krista Tippett: How does your reverence for Darwin . . . influence your sense of religion?

Gopnick: I always see Darwin as the model of the active explanation, the ethics of explanation. It affects my own feelings about the universe because it’s demonstrative about the possibility that you can be completely committed to a rational, material explanation of how we got here without being committed to a reductive account of our own experience. You can believe that there’s a completely rational account of how we got here but you can never fully rationalize what we feel here: it’s central to Darwin’s distinction between two different kinds of time. It’s the hardest reconciliation to attempt. That is that anybody who, like Darwin, is committed to science is acutely aware of the limits of scientific explanation. The greatest philosopher of science in the 20th century, Karl Popper, always said the realm of science was small. There is a huge realm of human experience that would never be susceptible to scientific explanation. That didn’t mean it could be subsumed into the supernatural. But there were realms of what for lack of a better word you call spiritual or numinous experience, or simply the experience of sensibility, everything summed up in . . . songs and poems and novels and spirituals all the other ways we have of organizing our experience . . . he believed he had discovered the secrets of life, but nothing could explain the mysteries of living.

Krista: Which is also the confusion that brings us to the religious part of life–community, texts, teaching.

Gopnick: And practices. I’m trying to write a book of memoirs on coming to New York in the 1980s. I was in the art world in those years. I was getting a degree in art history, God help me. I realized then that understanding modern art really was like a religion in that it was a practice before it was a dogma. You could never really get it by understanding the way one picture had changed another, how cubism had created expressionism which created surrealism and so on. It was a practice of interpretation. That is something that is insufficiently well understood. What religion brings us is a practice, not a dogma. The idea of having a spiritual practice is one that’s completely compatible with having a skepticism about dogma. Science demands that we be skeptical of our own theories.

Gopnik doesn’t quite get to the heart of it: religion and art aren’t simply about “feeling” or “sensibility.” But that’s more a limitation of the language, rather than a fault in his view–these are the words you end up resorting to, for lack of better terms. BTW, on the subject of art criticism, the Entitled Opinions episode on Diderot touches on how he approached each painting he wrote about without applying any formal system to his critique or response. You’ll also learn he was crazy about ice cream.

January 21st, 2016 by dave dorsey

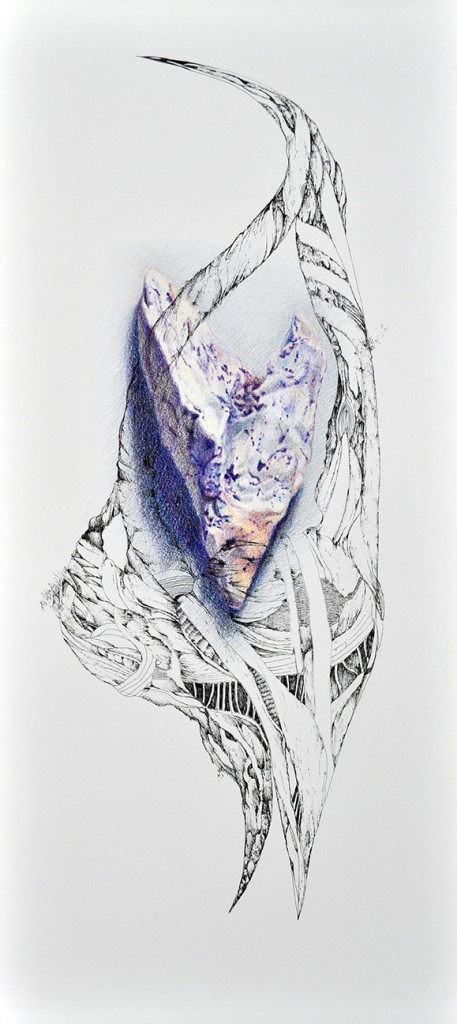

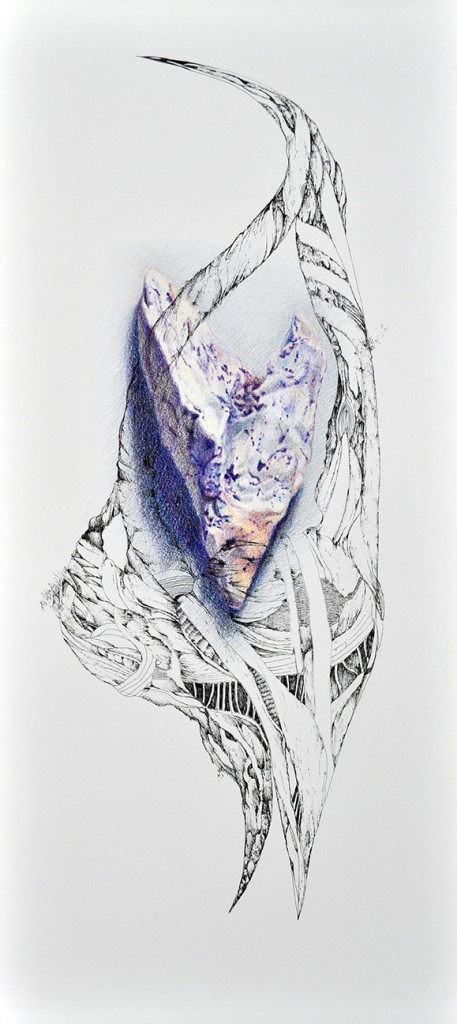

Bill writes about an upcoming show:

Bill writes about an upcoming show:

Been busy here in the studio, entered a couple of shows and continue to draw everyday. Jean and I collaborated on two works that will be shown @Makers Gallery and Studio opening on Valentines Day. The show will feature artist couples who were asked to produce 2 works combining each other skills and concepts. I attached one of the works for you to see.

January 19th, 2016 by dave dorsey

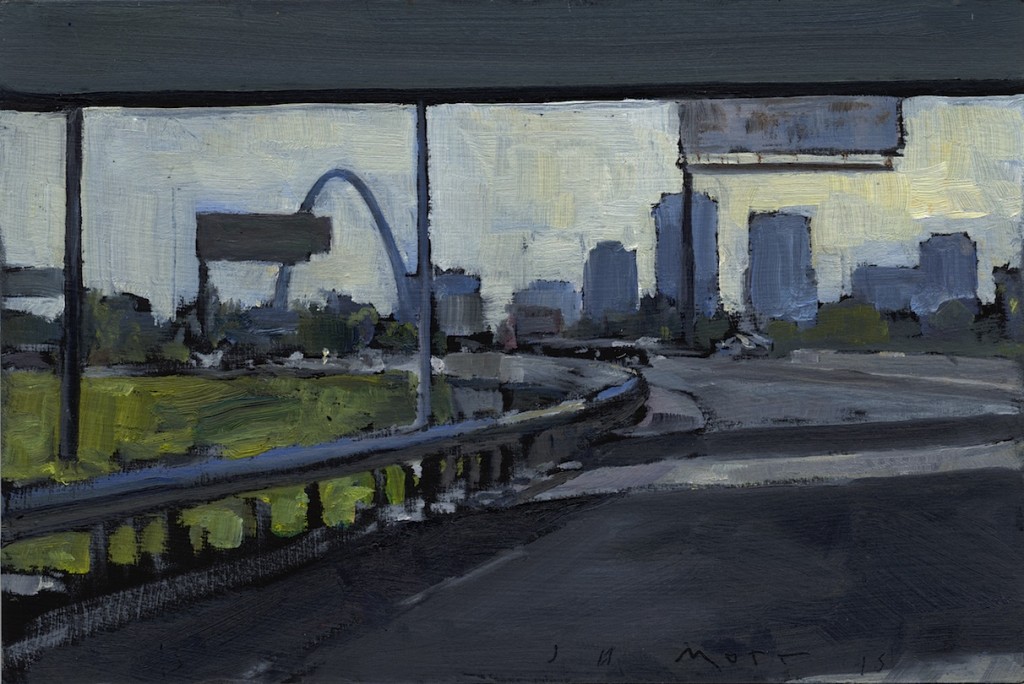

Jim Mott recently returned from what had to be his longest itinerant painting project, spending months on the road, and driving across the country, nearly coast-to-coast, and back again. He had lined up homes where he could stay,

MORE

January 17th, 2016 by dave dorsey

George Steiner, by Alecos Papadatos

I’m feeling a little Vichy lately, as I surrender to the forces that occupy my time and space. I’m openly collaborating with things that constrain me. My painting for now has become something I remember fondly. (I’m working a bit, but not nearly enough.) Mostly painting has become one of Walter Mitty’s heroic daydreams, something I can only crave to do, while my actual daily life has been overtaken by helping others. (Those who teach art must feel this way constantly.) And I’ve literally pushed myself into a corner. I’ve voluntarily moved my studio from the largest room on our first floor to an upper room, in a southern corner of the house, half the size of my studio for the past decade, but with much better light. I need that direct sun on a few days it appears; I can’t tolerate another gray Rochester winter with nothing but a northern exposure. I’ve fled to that room the way Van Gogh lit out for the Midi.

But all along, I feel as if I’m shoving myself aside, making room for everyone else to live in the space where I ought to be working. (My former studio, our new living room, has become our formal “parlor,” our living room. Which is what the space was designed to be. One of my wife’s friends asked her, “How did you get him to do that?” She said, “He did it all by himself.” She refrained from adding with a smile, “Lucky me.”) As with everything in life, while I do what I know is the most meaningful of all my efforts–caring for my parents and brother (who broke his arm over the holiday and can’t drive), spending time with my children and grand-daughter for a week, reuniting with my little band of brothers from college earlier last year–I feel I’m neglecting my real work. Helping others is easier, because my social life actually requires so much less effort than making a picture. It feels as if I’m on a vacation, being irresponsible. It’s frustrating only because it’s time consuming. While the actual meaning in my life is hidden there in those tedious hours of helping out, whenever I sacrifice work time for the people who matter to me, I’m discouraged because I can’t make meaning by creating a picture. Why worry about making meaning? It’s already there in everything I’m doing–but mostly what I feel MORE

January 10th, 2016 by dave dorsey

January 8th, 2016 by dave dorsey

A Guide to the New Elizabethans, Diarmuid Kelley, oil on linen, 60 x 53 1/2

More here.

January 3rd, 2016 by dave dorsey

Most writing on art is by people who are not artists: thus all the misconceptions.

—Eugène Delacroix

That’s a quote from a book excerpt in the latest Atlantic about storytelling, which has some references to painting, and a nice quote from Robert Hughes. My life right now has been and will continue to be a long obstacle course that keeps me from painting, and I expect not to be able to get back to it for another couple months. After a year of multiple demands on my time–some of them voluntary, like my ride through New England, but most unavoidable–I’m facing two months with a total focus on some bread-winning writing, which is interesting and challenging, but may be my last chance to keep making a living at it. If it doesn’t succeed, I’ll have far more time to paint, but it will mean less income at an age when I don’t have many options left. Right now, all I want to do is get back to painting. All in due time. My down time is forcing me to imagine where I want to go, when I get back to the easel, and that’s what I’m doing, with some good results. It’s frustrating to have to keep waiting to act on it, though. But at least I’ll be ready and focused when I can.