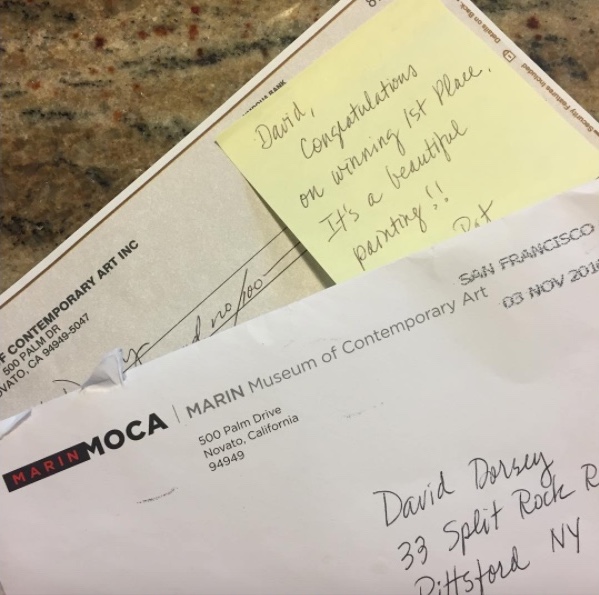

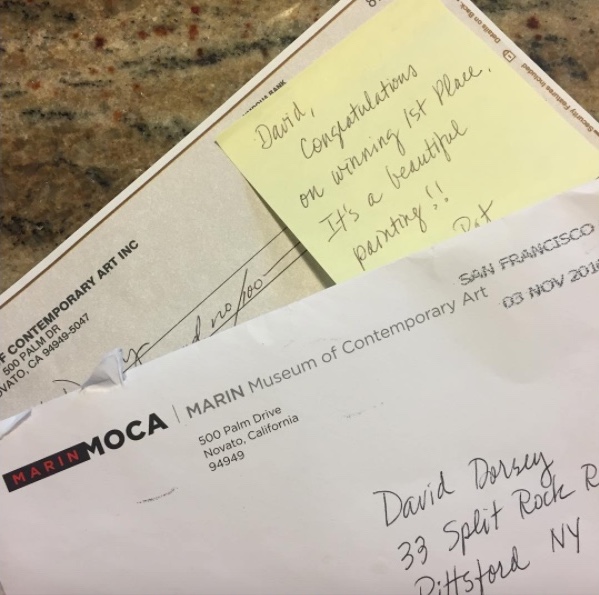

November 25th, 2016 by dave dorsey

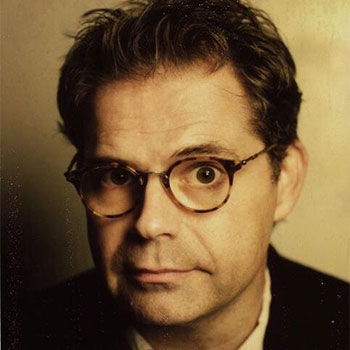

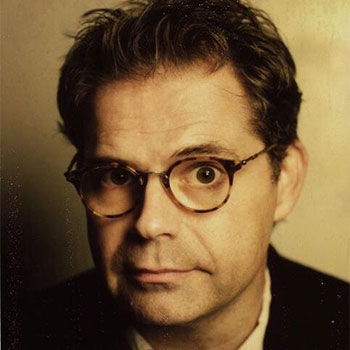

Dana Gould

Dana Gould served as a guest host on Kevin Pollak’s podcast recently, and he had this exchange with his guest. I love the term “jam econo,” which isn’t just about money.

Jonah Ray: A lot of people want fame and money and if they have a knack for comedy they use that to get fame and money . . . lot of people go too big (in) how they go about things. Mike Watt, of the Minutemen, has this saying, “We jam econo.” Stay within your means. Do what you can within your own self. Don’t get further in your life or career on credit. Do it within your realm of possibilities.

Dana Gould: That was an understanding I came to about my stand-up career, and I think this applies to all people who consider themselves craftsmen or artists. It took me decades to come to this conclusion. So much of your career is, “if I get this, then I’ll get this.” Your career is now. You’re here. This is it. It’s great. If you are actively building your career, you’ve made it. If you are working at Barnes & Noble trying to gin up the balls to do an open mike, you haven’t made it. If you do an open mike, you’ve made it. The rest is just a level of degree.

November 24th, 2016 by dave dorsey

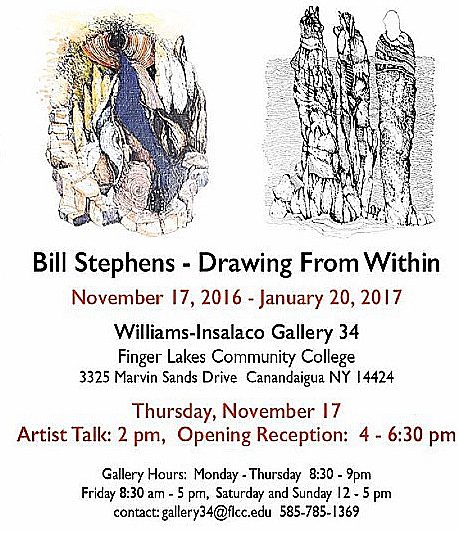

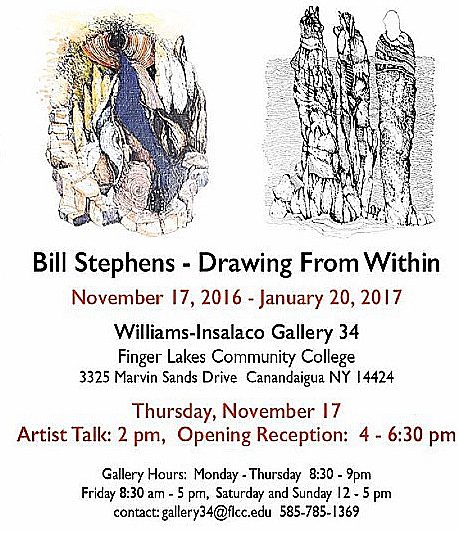

Drawing from Within, a solo show of drawings by Bill Stephens, is on view in the Wayne Williams and Tom Insalaco Gallery at Finger Lakes Community College. It isn’t a large space, but Bill’s drawings fit perfectly into it, and the show makes a striking impression when you walk in. Everything is framed and matted in such a way that his line drawings look, at a glance, as intricate as old engravings. He uses pens with an extremely fine point, creating form with cross-hatchings, Durer-like, never using solid blacks or grays. I’ve seen previews of this work at our get-togethers for coffee, and I’ve always been impressed, but the work makes a much deeper impression when you see it gathered together this way–the cumulative effect demonstrates how consistently his vision has emerged in this new direction for his work. His world holds together, stylistically, from each drawing to the next. They offer glimpses, from slightly different angles, into his unique and integrated inner world. Some of his images look almost like illustrations from Dante: clusters of souls migrating toward something beyond themselves.

What’s most interesting to me about Bill’s work is that the drawings are the outcome of a process rather than an attempt to render something already visible. His puts down lines and follows where they lead him, a journey to discover the forms that emerge as he improvises his way to an image that often fuses landscapes with botanical, animal, and human shapes. Everything seems an extension of everything else. The end result is surrealistic, and his process echoes surrealism’s “automatic writing,” letting the subconscious guide the hand. Yet as much as I was surprised to be reminded of Dali in many of these drawings, the feelings they evoke are far from the cool theatricality of Dali’s eerie, melting shapes. He’s enthralled by nature, and his enthusiasm infuses everything with a warm energy. He isn’t wedded to any particular sort of landscape–you can find echoes of his wooded Western New York backyard as well as the mesas of the Southwest. Mostly these are dreamscapes where vaguely recognizable forms emerge from the least expected sources–much of what he depicts seems to want to grow a pair of legs, even rock formations.

Bill’s talk about how and why he draws was completely extemporaneous and casual, yet it was often eloquent, and consistently illuminating. He says that each time he sits down in the morning in his studio, he brings a beginner’s mind to what he’s about to draw. For reference, he often refers to the notebooks he fills with quick, adept sketches when he travels, many times jotting quick, haiku-like impressions in the margins. He passed around these notebooks during his talk. The words hover around the edges, subordinate to the drawings. He and his wife, Jean, also an accomplished artist, are both enthralled by nature, and in their work they invest a spiritual depth into the simplest, most common and familiar aspects of the natural world, animal, plant and mineral.

In the days since Bill’s talk, having seen how intensely he’s venturing into this new series without knowing where it will lead, I’ve begun to realize that his process is, for me, a microcosm of how an artist’s career ought to evolve. The best work emerges from an effort to do something more and more consonant with the inarticulate feel of applying a medium in a certain way to a support–without knowing exactly where the effort will take you.The more you let other considerations come into play, the more they drain the life from the final image. Bill Santelli rode down to the show with me and on the way back we talked about how hard it is to stay focused on this factor of feeling one’s way forward in a particular painting, and, in a larger sense, in one’s career. The only reliable guide is to simply keep attempting to paint, or draw, what you most want to see. And you can work for years, or decades, without quite knowing what that is–or be constantly struggling to stay focused on it. Paint only what you want to look at: it sounds like the easiest thing in the world, but everything conspires to make you ignore that desire for any number of reasons: because what you might do won’t sell, or get shown, or be critically recognized, or because you want to belong to a particular “school” of work that has other requirements for admission. In these drawings, Stephens is answering only to what he wants to see emerge, line by line, and drawing by drawing, without any other consideration in play. And yet, groping forward in this way, sticking to process, he gets results that have an unexpected imaginative resonance.

In The Duino Elegies, Rilke spoke about how nature wants to “become invisible” through a certain kind of human reverence for it:

Earth, is it not this that you want: to rise

invisibly in us? – Is that not your dream,

to be invisible, one day? – Earth! Invisible!

What is your urgent command if not transformation?

I suspect in Rilke’s own life, this meant translating the tangible world into poetry. With Stephens, it’s just the reverse. His line, as he puts it down, creates its own necessity, so that while he draws he isn’t copying what he sees, but rather hopes his experience of nature will be translated, subconsciously, into tangible images that convey what might otherwise remain invisible, even to himself.

November 18th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Candy Jar #9, oil on canvas, 52″ x 52″

Candy Jar #9 will be awarded Best in Show tonight at The Red Biennial, presented by The Cambridge Art Association, on view at the Kathryn Schultz Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The exhibition was jurored by Joseph D. Ketner II, the Henry and Lois Foster Chair in Contemporary Art Theory and Practice at Emerson College, Boston. He also holds the position of distinguished Curator-in-Residence. His professional expertise is as a curator and art historian specializing in European and American Modern and Contemporary Art, and nineteenth-century African-American art.

November 14th, 2016 by dave dorsey

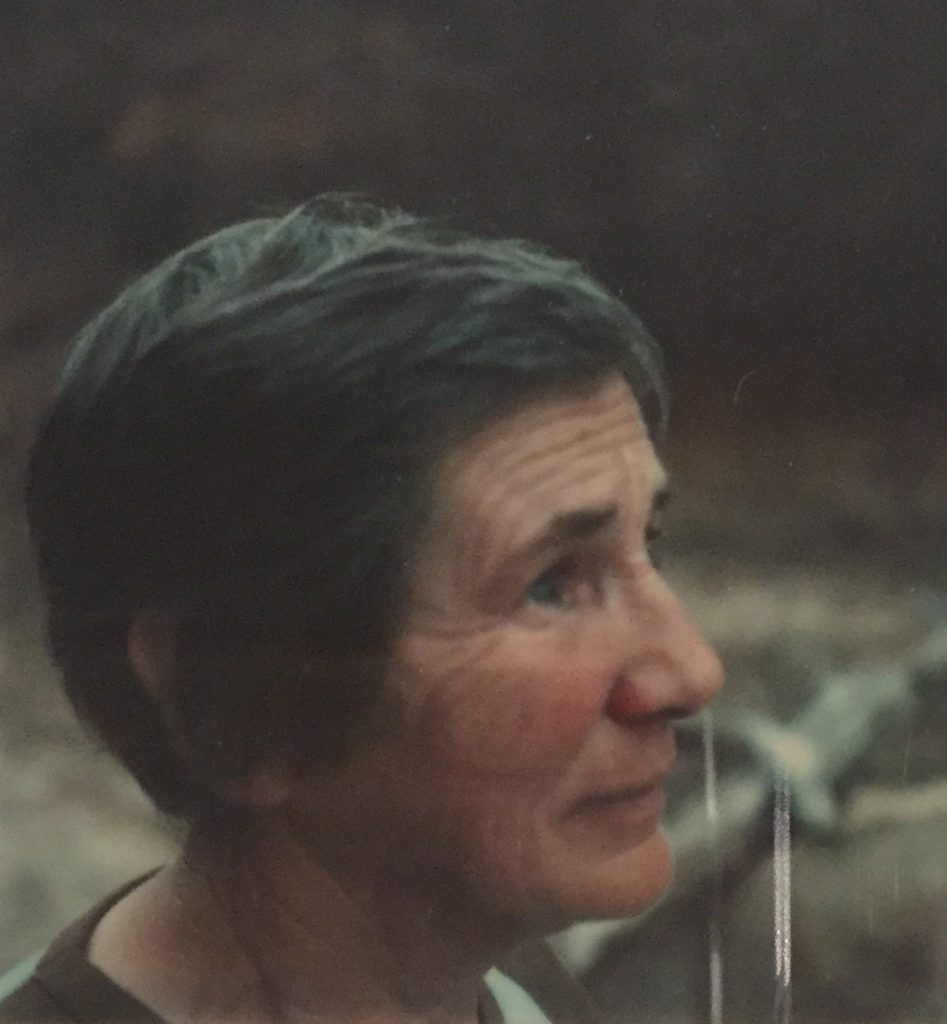

Agnes Martin, Cuba, New Mexico, 1970s

“You have to have a mind of winter to see nothing that is not there, and the nothing that is.” — Wallace Stevens

1

Agnes Martin painted like a thief. She seemed to be attempting to leave behind as little evidence of herself–or anything else–whenever she touched a canvas. It’s a self-effacing posture consistent with her immersion in Taoist spiritual traditions, and it’s part of what gives the rigorous austerity of her work its humble charm in the current Guggenheim retrospective. Yet as impersonal as the work appears, it’s often as beguiling as a simple, four- or five-note melody from nursery school. You climb the whorl of the Guggenheim’s spiral gallery, craving more than what’s there for much of the way. It makes you hungry for color, expecting to get it once you reach that museum’s higher elevations. Yet when it arrives, it leaves you wanting even more. Her tones are as faint and subtle as the pinks and blues in a Turner dawn. Meanwhile, there’s almost nothing to see in one pencilled spreadsheet grid after another, rows and columns of rectangles stacked on rectangles, each one as empty as the next. Then you’ll suddenly come upon a large, thin veil of paint that looks as soft and sensuous as felt or velour. The paint has a surface Thiebaud would have appreciated, though its almost the opposite of his impasto, more like a faint layer of powdered sugar on a cushion of icing, and, as if to heighten the effect through contrast, she scores that paint with a net of lines drawn into the still-soft medium. Again and again you feel a serene tension between the extreme simplicity of her means — the near-absence of all form — and the often sensuous, tactile surface, where the weave of the fabric, the absorbent gesso and finally the thin washes of paint all fuse to become a physical object that looks as if it were made to be stroked with your fingertips. (Which is an interesting urge considering the fact that she maintained she was trying to visualize an immaterial, spiritual state.) While the painting does seem to convey a state of mind, it also seduces you with its physicality. You note these polarities only if you stand and look with persistence, surrender to the static hum of her color or lack of it. Her art requires you to slow down and gives you almost nothing to think about. Judging from the evidence in this retrospective, it’s probably safe to assume she was constantly wondering how one might translate into paint the “no-mind” of Ch’an Buddhism’s Sixth Patriarch: awaken the mind without attaching it to anything.

2

I had never heard of Agnes Martin until four or five years ago, when for the first time I came upon one of her paintings, Untitled #6, at the MORE

November 9th, 2016 by dave dorsey

I’ll be there for the talk, and for a tour of the show. I’ve been watching Bill work on this series for a while, and own one of the best ones he’s done. It’s fascinating work, and I have a sense that Bill is always balancing between conscious technique and subconscious impulse, tending the process without quite controlling where it leads or knowing where the drawing is going to end up. It unveils itself to him, as much as it does for the viewer. The one in my collection feels like an illustration for Dante’s Inferno, but a lot of the work seems biomorphic, the forms growing as naturally as seeds and branches.

November 7th, 2016 by dave dorsey