May 28th, 2017 by dave dorsey

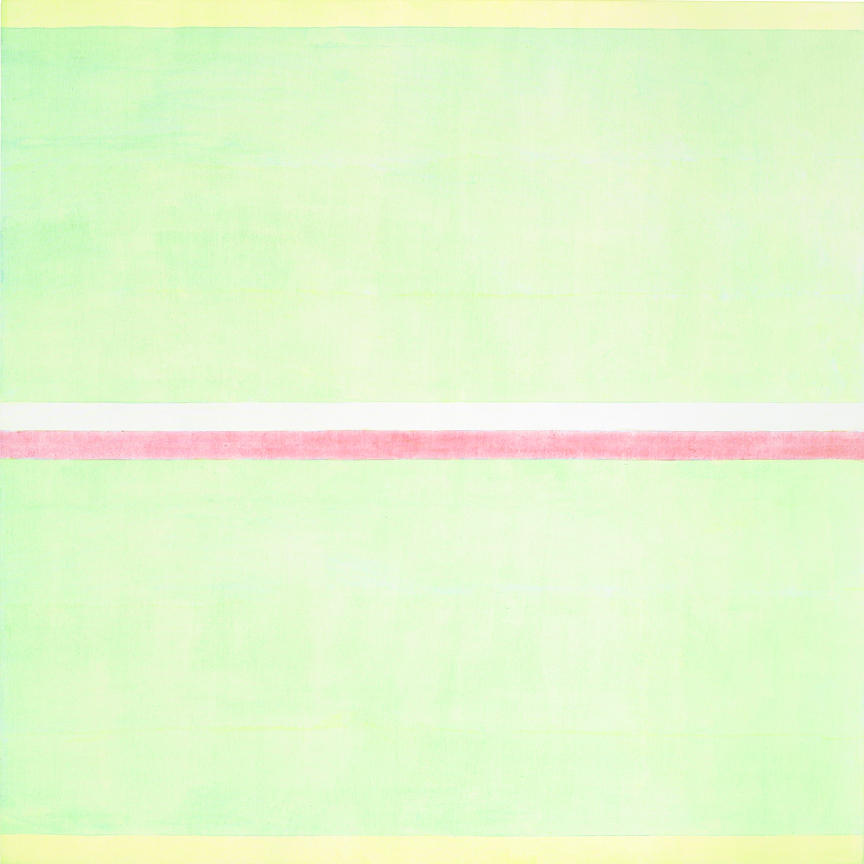

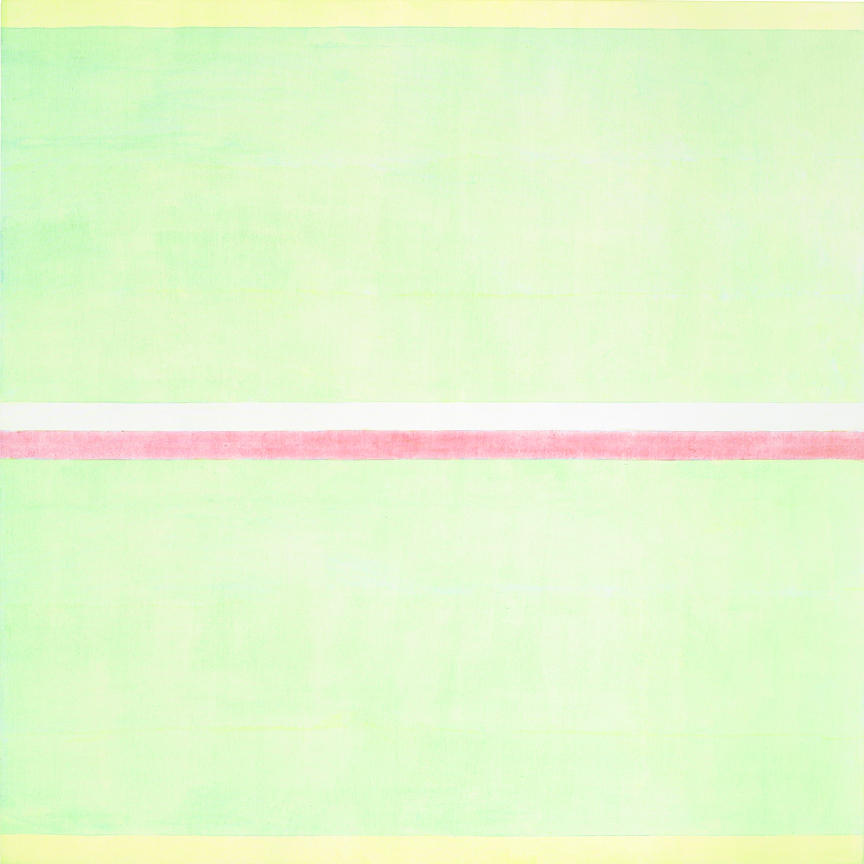

Agnes Martin, Gratitude, 2001, acrylic and graphite on canvas, 60 x 60 inches

Thoughts on how not to think, from Agnes Martin:

The life of an artist is a very good opportunity for life.

When we realize that we can see life we gradually give up the things that stand in the way of our complete awareness.

As we paint we move along step by step. We realize that we are guided in our work by awareness of life.

We are guided to greater expression of awareness and devotion to life.

You must say to yourself: “How can I best step into this state of mind and devote myself to the expression of life.”

You must not be led astray into the illustration of ideas because that is not art work. It is ineffective even though it is often accepted for a short time. it does not contribute to happiness and it is finally discarded.

The art work in the Metropolitan Museum or the British Museum does not illustrate ideas.

The great and fatal pitfall in the art field and in life is dependence on the intellect rather than inspiration.

Dependence on intellect means a consideration of observed facts and deductions from observation as a guide in life.

Dependence on inspiration means dependence on consciousness, a growing consciousness that develops from awareness of beauty and happiness.

To live and work by inspiration you have to stop thinking.

You have to hold your mind still in order to hear inspiration clearly.

May 25th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Introspection, Dario Tazzioli, carrara marble.

I had some fascinating conversations with fellow artists at the reception for Doppelgangers at Oxford Gallery, where Jim and Ginny Hall have assembled another fine group show. It drew a large crowd, and it may have offered the largest number of pieces of any show they’ve ever put together, more than sixty. Many of the contributors took the theme as a pretext for submitting a pair of works, some two- and some three-dimensional, and yet everything seemed to fit perfectly into the available space. The idea of doppelgangers inspired or at least drew some exceptional work that had already been completed. As always, it’s impossible to do justice to everything on view, but again Dario Tazzioli’s sculpture was a magical affirmation that the artistic past is also its present and future. His Introspection, the bust of a young woman with a mane of flowing, wavy hair, carrara marble carved with a hand-turned bow drill—delivered to the show from Italy—stands as a quiet traditional tour de force, a testament to how nothing is off the table in art now. “Anything goes in art” used to mean that Warhol could fill a room with balloons and call it a masterpiece; now it means that the heritage of Donatello can still speak powerfully to a contemporary audience.

Tom Insalaco’s two paintings of faces offer the same lesson in a darker mood. They are the work of a man who has, for decades, been inspired by and driven to honor the Renaissance and baroque periods. He continues to quietly labor at his home studio in Canandaigua, NY, with more than one room turned into warehouses for his past work, all of it deserving a serious retrospective, but as if often the case with brilliant work done in obscurity, no one seems to be knocking on his door offering to revive interest in his remarkable career, which moved over the years from photo-realism to a reverence for the Old Masters. Since last year I’ve been studying and reading about Piero Della Francesca, whose work, especially, toward the end of his life, strikes me as powerfully alive and evocative and stylistically individuated in a completely contemporary way—which again suggests that emulating the mannerists or the Old Masters or the early Renaissance, or any other period, doesn’t need to be even a quasi-ironic undertaking, as it is with John Currin or Kehinde Wylie.

I had a long, probing conversation with Phyllis Bryce Ely about the recent work of hers I’d seen earlier in the day at Main Street Arts in Clifton Springs, NY: MORE

May 7th, 2017 by dave dorsey

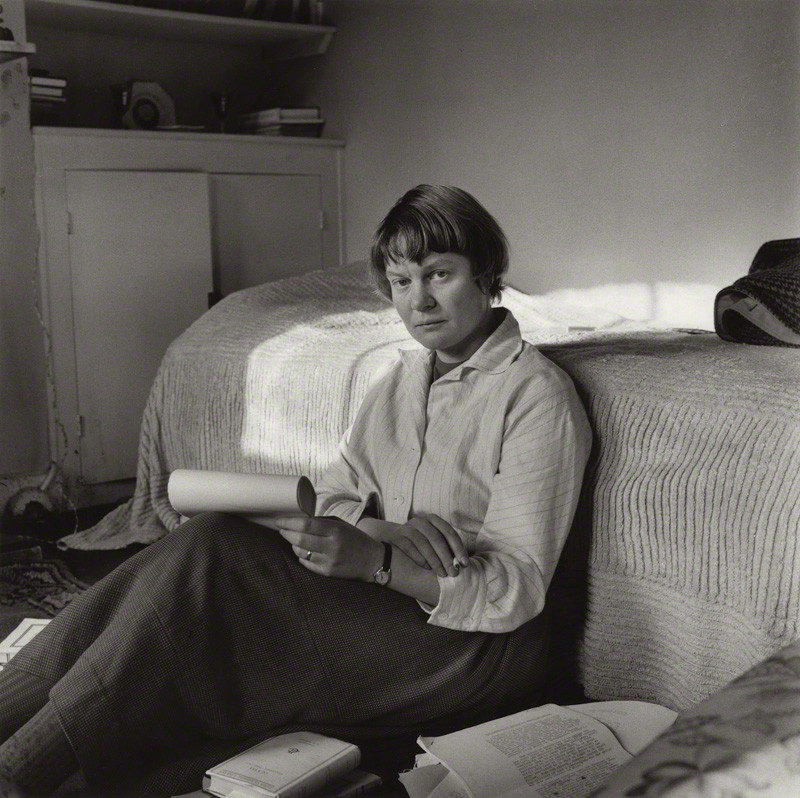

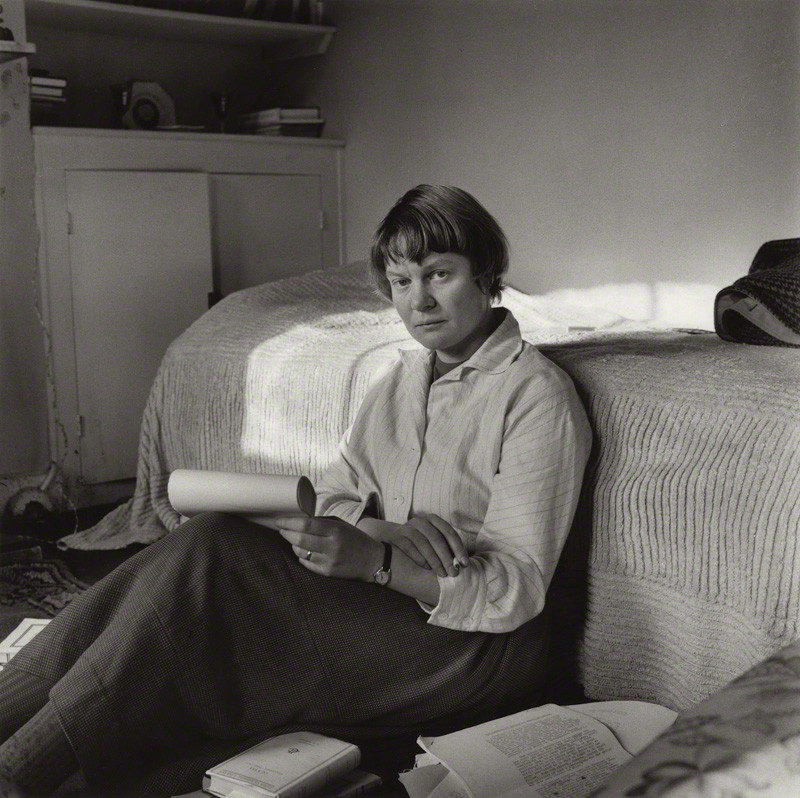

Iris Murdoch, by Ida Kar, 1957 National Portrait Gallery

Iris Murdoch, from Existentialists and Mystics:

Following a hint in Plato (Phaedrus, 250) I shall start by speaking of what is perhaps the most obvious thing in our surroundings which is an occasion for ‘unselfing’, and that is what is popularly called beauty. Recent philosophers tend to avoid this term because they prefer to talk of reasons rather than of experiences. But the implication of experience with beauty seems to me to be something of great importance that should not be by-passed in favor of analysis of critical vocabularies. Beauty is the convenient and traditional name of something that art and nature share, and which gives a fairly clear sense to the idea of quality of experience and change of consciousness. I am looking out of my window in an anxious and resentful state of mind, oblivious of my surroundings, brooding perhaps on some damage done to my prestige. Then suddenly I observe a hovering kestrel. In a moment everything is altered. The brooding self with its hurt vanity has disappeared. There is nothing now but kestrel. And when I return to thinking of the other matter it seems less important. And of course this is something that we may also do deliberately: give mention to nature in order to clear our minds of selfish care. It may seem odd to start the argument against what I have roughly labeled as ‘Romanticism’ by using the case of attention to nature. In fact, I do not think that any of the great Romantics really believed that we receive but what we give and in our life alone does nature live, although the lesser ones tended to follow Kant’s lead and use nature as an occasion for exalted self-feeling. The great Romantics, including the one I have just quoted, transcended ‘Romanticism’. A self-directed enjoyment of nature seems to me to be something forced. More naturally, as well as more properly, we take a self-forgetful pleasure in the sheer alien pointless independent existence of animals, birds, stones and trees. ‘Not how the world is, but that it is, is the mystical.’*

I take this starting point, not because I think it is the most important place of moral change, but because I think it is the most accessible one. It is so patently a good thing to take delight in flowers MORE