Archive for October, 2017

October 29th, 2017 by dave dorsey

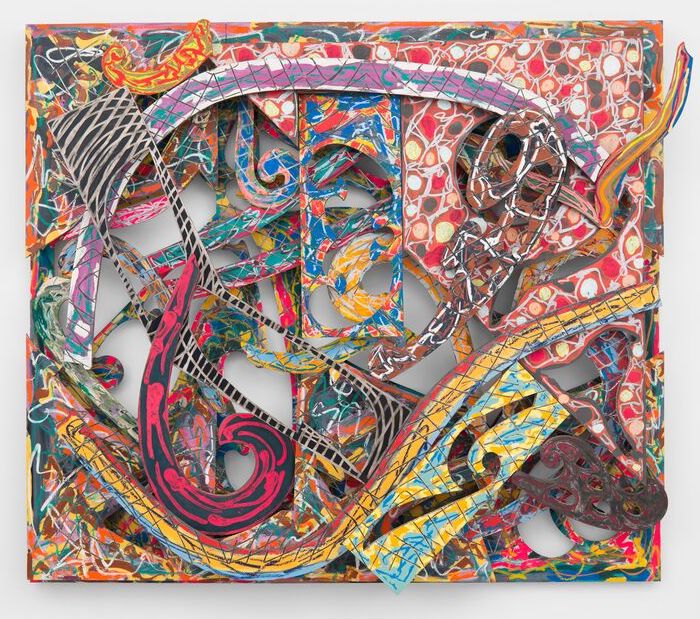

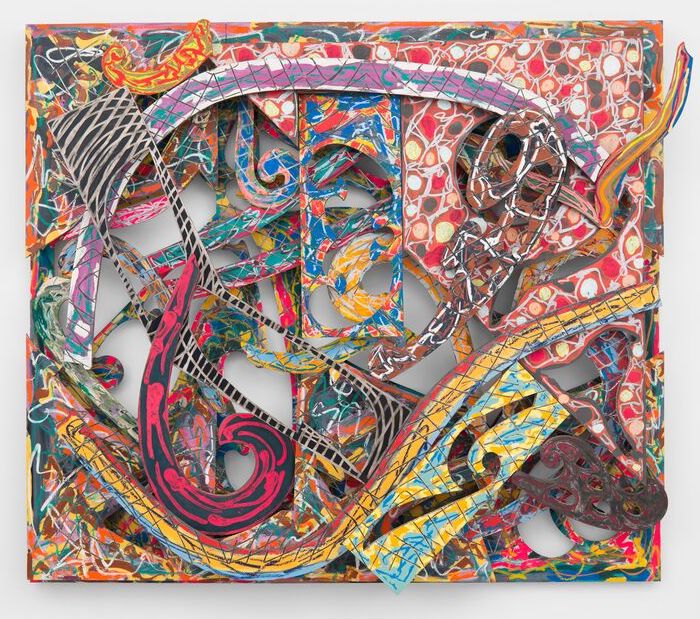

Frank Stella, Mosport 4.75x (1982), © 2015 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

I couldn’t have put this any better, from the beginning of an essay by Robert Linsley a few years ago on the occasion of a Stella retrospective in Europe. My only quibble is that I’m not sure I see any intellectual side to Stella’s best work (one reason I love it), which Lindsay seems to suggest in a paradoxical way further on, when he talks about feeling the artist behind the work without any conceptual screen between viewer and artist. Art is immediate, even though it can take years coming back to it to actually see and feel a painting directly, and this passage bears that out even though it starts inauspiciously with critic-speak about “voiding of the subjective” while then offering the counterpoint of “feel the artist behind the decisions,” which is what he’s really describing:

I’ve enjoyed Frank Stella’s art since my own beginning as an artist, and the crucial thing has been the enjoyment. The intellectual or theoretical side was always evident—the literalness or factuality, the deliberate voiding of the subjective—and I never needed to take a course or read a tract to feel its necessity or reason, but overriding for me was the pleasure that accompanied the fact that I could also feel the artist behind the decisions. I had a particular affection for the Protractors, although it was many years before I saw one of the original Black Paintings in person, and felt how strongly emotional and romantic they are. I find myself thinking back to those early days in art because recently I’ve acquired a real love for Stella’s Moby Dick series. . . I’ve known about them since they were made, in the late eighties, and always thought they were an important group of works, but only very lately have I really seen them, with a return to feelings about art that perhaps one only has when young. Inspiration means an intake of breath—the breath of life, being whatever one needs and wants to find in art. For me, Picasso, Matisse, Cézanne, and intermittently many others, were truly inspiring—they filled me with a sense of the possibilities of life. Emulation was the necessary beginning, but eventually I had to meet the challenge that was presented, to breath out and keep on breathing. In those days I drank in their work and always had a thirst for more, or, to return to the metaphor of inspiration, the fresh air of art brought every cell to life. Looking at art books was a daily pleasure that gave a perspective on the ordinary dullness of life; visits to museums were transformative. Every contact with art sent me back to the studio. I never had a “disinterested” response to beauty, for me it was always about what could be done—what had been done and what I could do, and every historical achievement was another possible path forward. This practical, achievement oriented attitude is why I like Stella’s writing, which is exactly that way, but I never expected to have such strong feelings about his work. Today I just want to stand beside the Moby Dick reliefs and feel the energy. It’s the unexpectedness of this response that, for me, proves its truth.

October 26th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Upstairs View, Eve Mansdorf, oil on linen, 26 x 30

October 23rd, 2017 by dave dorsey

Hell, rising from a thousand thrones, oil on canvas, 77″ x 77″, Dolby Chadwick

October 20th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Breakfast With Golden Raspberries, oil on linen, 22″ x 46″

I was humbly surprised to be informed recently that I’m a finalist for the Manifest Grand Jury Prize, with a cash award of $2,500, which will be bestowed on the best single work exhibited in the entire 13th season at Manifest Gallery. This means the organization’s panel picked Breakfast with Golden Raspberries as the best work in its particular exhibit earlier this year. The final award will involve the contribution of as many as 20 jurors and the few dozen works under consideration will have been culled from more than 15,000 entries to all of the Manifest shows throughout the past season.

Here’s a summary of the process from the notification:

I’m writing to notify you that, now that our 13th season has concluded (and we’ve gotten #14 off to a good start) we’re launching the final stage of the Manifest Grand Jury Prize for your exhibition season, and your work is among the finalists to be considered.

Since we announced the MGJP partway through the season you may or may not be aware of all it entails. Rest assured, there is little you will have to do, although we hope you’ll chat about it in your networks, share your success to this stage, and, if you win, shout it from the rooftops. If you would like further information and background, rather than belabor it here, I’ll ask that you read up on the prize at

http://www.manifestgallery.org/about/awards/grand_jury_prize.

In short, your works were scored the highest by our jury (either alone or tied with others) in the exhibition in which you participated. The entire pool of works, out of many hundred we exhibited across 30 exhibits during the season, are those which did likewise. This pool comprises approximately 40 works.

I’m delighted to have gotten this recognition for a painting that won awards in two other shows last year, including a best in show at Marin MOCA.

I recently told Jim Hall, at Oxford Gallery, that I loved this painting. He laughed and said, “If you do say so yourself.” I laughed along with him, because what I really meant is that there is nothing in this painting that bugs me. To say I love it is, in my lexicon, essentially to say it doesn’t trouble me. (It’s a little more than that, but not much.) Normally, in almost every painting I complete, something continues to bother me about it, something I am at a loss for how to fix–or too cowardly to risk messing up the painting by attempting to fix it. In this painting there is nothing that needs fixing, and that’s a very rare quality in one of my paintings. In a painting I’m finishing now, another small still life with a patterned bowl–I keep going back to them–I’m very happy and surprised by much of the canvas, but one particular area of the background continues to bother me. It doesn’t look wrong or bad, but something in it just subliminally nags at me as not quite right. It’s fine, and few other people would see anything amiss, but something about those distant kitchen cabinets keeps asking for adjustment. I went after it this morning but even as I completed the amendment, I was wondering how to neutralize, just slightly, the color of that sector. As Sam Kinison said so immortally, it never ends.

Sometimes it does end, though–as with this award winner. No matter how often I look at it, I know it’s done. And nothing about it bugs me.

October 17th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Two Paint Cans, Wayne Thiebaud

More Thiebaud, on how he isn’t and was never a Pop artist, is self-taught, and doesn’t trust art that’s rooted in ideas, from another book published in the same year as the one in the last post, Realists at Work, John Arthur, Watson-Guptill, New York, 1983:

You’ve described yourself as a self-taught painter. Does that mean you didn’t study painting?

No. I started as a sign painter and did fashion illustration, furniture drawing, lettering, and cartooning without going to school. At twenty-eight or twenty-nine, when I went back to college, I got credit for most art courses by special examination by that time I had exhibits, Army experience, and so on. I have courses on my record showing I studied painting and drawing, but those were generally by challenge; they just gave me grades. I took art history, courses like the psychology of art, lots of art education courses, but no formal training.

I believe I saw your rows of pies in Life magazine in the early sixties. Your work kept getting linked with Pop Art at that time, which I thought was a bit of a distortion. Much of Pop Art relied on the look of mechanical processes and played down the effect of the hand.

If anything, my interest was the opposite, more out of the tradition of Velazquez, Manet, to Eakins, through people like Jasper John and Richard Diebenkorn, for whom the signature gesture is central.

When I painted the first row of pies, I can remember sitting and laughing—sort of a silly relief—“Now I have flipped out!” The one thing that allowed me to do that was having been a cartoonist. I did one and thought, “That’s really crazy, but no one is going to look at these things anyway, so what the heck.”

Some people have talked about the irony in my work and the idea terrifies me. That’s something I’m not interested in on a conscious level, and the reason I’m not is because that kind of explication of an idea vitiates its power. If I were using what intelligence I have to be ironic, I couldn’t be smart enough for myself. I would be disappointed, and I’m generally disappointed in irony for that very reason. It seems self-explanatory and anticipatory in a way that never interests me. The reason I don’t like classical surrealism if there is such a thing, is that it seems already to have arrived before you’ve seen it. Even a good painter like Magritte—his ideas put me off.

You may be opposed to irony, Wayne, but not to wit.

No, I think wit is a very high form of attainment. Any kind of wit is one of the toughest things to do. Also, it’s one of the things that’s missing in so much of the art world. When you lose the capacity for a sense of humor in an art form, you lose a sense of perspective.

I was just talking to Harry Rand, who wrote a book on Gorky, about how, when you get so you can do something, you don’t want to do it anymore, and he said, “Yeah, that’s very hard, but I think one of the things that painters have to learn is that it’s all right once in a while to shoot fish in a barrel.”

October 14th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Art history in its essence is an organic, growing, and changing discipline. It’s more like a private game refuge, a treasure of exotic and wonderful rare Art Beasts. And our interests continue to change as we find out more and more. It’s hard for me to recognize something like progress or evolutionary development, say in a Darwinian sense, in the development of art. For instance, though I’ve conscientiously studied his paintings for many years, I just can’t find anything new, conceptually, in Paul Cezanne. For me he’s just a damn good painter, who’s using practically every device, convention, and trick in a painting, but he was so terrific, so bright, so careful in trying to be true to his relationships, that the painting is different, not because of any invention, despite his beliefs, but because of the composite structure and complexity of his perceptions translated into paintings.

–Wayne Thiebaud, from Art of the Real, edit. Mark Strand, Robert Hughes forward, Clarkson N. Potter, New York, 1983

In the fewest possible words, and his typically humble voice, Wayne Thiebaud here says nearly everything an artist needs to know about his or her relevance at any given place or time in the world of art. To wit: the historical sense of place and time don’t matter now. Everything is permitted; but only a few things are worthwhile. Thiebaud came to this realization after Arthur Danto did, but before Danto started talking much about it in 1995. By the 60s, when Thiebaud emerged by being mistakenly classified as a Pop artist, it became possible to do anything and call it art. There were no longer any limitations on what could be considered a work of art, something Duchamp asserted decades before, but it was a cynical declaration of freedom that didn’t flourish until the Pop artists adopted that same philosophical stance and liberated artists to do whatever they wished. The ironies embedded in Pop’s appropriations struck Danto as an integral part of the game, I think, but irony isn’t required and if anything it cheapens much of Pop and makes it far less interesting than it ought to be. (Don’t forget that Pop gave us Jim Dine.) It’s now entirely possible to paint like an Old Master without a postmodern smirk (some of Richter for example)—because the work has the same power now as it did hundreds of years ago. What Thiebaud is trying to say, and which remains difficult to articulate clearly, is that an authentic individuality matters more than any other consideration in art—and this individuality is infused into a painting subconsciously, not by choice. It’s about style, not stylization, as Susan Sontag said. Style is involuntary. A painting needs to be an extension, a replication not necessarily of something seen but of the wholeness of a painter’s identity, “the composite structure and complexity of his perceptions translated into paintings.” It has nothing to do with conceptual justifications or ideas or meanings and messages. A painting is more like a sacrament, a host for the life of the painter, than an expression of something a painter simply thinks up. It isn’t about thought, and it isn’t about hewing to anything but what an individual’s need to paint requires, which is something to be learned anew with each painting, something felt rather than known, discovered through act and instinct and a physical struggle with the qualities of paint.

October 11th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Taffy #1, Oil on Linen, 46″ x 46″

Standing Taffy

This cairn of taffy squeezes

into shapes that Hammersley,

Stella, or Matisse

might have liked, loopy

curves of subtle tones,

color contained, simple as a tune

or cream uncoiling into a cup.

Stacked, unstable acrobats

lean, and come near

to teetering onto stone.

There’s a timid cheer

in their defeated smiles

that spiral through caramel,

raspberry and peach,

those fields of foggy color

wrapped in wax

and twist-tied into chipper bows.

Sweets, created to melt

into fleet flavors,

no one can respect,

nor put to use,

signifying nil but the need to please.

Dimpled, dented, crumpled,

they sag as if under more

than the punished bulk

of one (or two) of their own.

Those wings will never fly, guys,

but you’re serenely ready

in the purity of your hues

to stand for nothing but what you are.

October 8th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Chevron Bowl, oil on linen, 12″ x 16″

I was pleased to learn that Minot State University purchased Chevron Bowl, which was included in Americas: All Media 2017. As a part of the school’s permanent collection it can be exhibited and also used as a teaching tool. It has always seemed that the school puts a special emphasis on printmaking exhibitions, so it seems appropriate that they wanted to hold onto this painting. It’s one of my best efforts in a more painterly approach to the process of making a picture, one in which I’m often thinking about the techniques of serigraphy. With all of my work now I apply a first layer of paint in discreet areas of uniform color, with an effort to establish the right value relationships between these flat shapes, so that the hue may be off here and there, but the image breaks down properly into lights and darks. Then I go to work within these sections of flat color, adding detail and tweaking color, both in my typical, painstakingly realistic work, and in less defined paintings like this one, where the effort is to work wet-on-wet, keeping the premier coup quality of the paint–and maintaining the sense of flat patterns established in the first application of paint.

In both processes I want to develop the painting in stages, keeping corrections to a minimum so that the color remains fresh and alive, yet with paintings like Chevron Bowl I want the ghost of flatness, as it were, to be an active element in the viewing experience. I want what the viewer sees in this work to waver just a bit between two and three dimensions. I want areas of color to remain as uniform as possible, which means I sacrifice precise, granular detail for the sake of preserving the evidence of my brush and hand. The execution becomes much simpler and the quality of light in a painting like this feels more delicate and resonant, the paint a bit less opaque. Because you’re not looking at something rendered with a sense of photographic accuracy, the mind is attending to both the paint itself and what the paint seduces your mind into seeing. In that conflict, the frisson of those two things–the image of the world I’m creating and the flat pattern of paint on cloth–I’m trying to bring a certain kind of life to the work different from what’s there in the verisimilitude of my more extremely realistic work.

October 5th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Now that he lives in Oregon, instead of Western New York, I don’t get a chance to have coffee with Rick Harrington anymore, and I miss it. I think the last time I saw him was at his home and studio here, after he’d had his first surgery on his vocal chords. He used to be the loudest guy in the room; now he sounds more like Super Dave Osbourne leaning over to say something in a movie theater. His surgery saved his life, probably, but for a long, long time, the anesthesia dulled his brain in a way that made him wonder, as many of us do, about signs of early-onset something or other. But he’s come out of the fog and sounds like a new man. As he puts it here, he got lost in his mind. I thought I would pass this especially interesting and encouraging post, after a long silence:

OK, so it happened. I was warned, and didn’t act quickly enough. Nothing like a friend thinking maybe you’d died to get you off the dime.

A couple months ago we were in New York, on Long Island, visiting my marketing consultant. I’m her favorite pro-bono client, the sort of privilege you get when your daughter happens to be a spectacular designer. I’ve been futzing over a new logo/identity, which she usually lets me muddle through on my own until I go astray with type and such. Then she shepherds me back in, (i.e., takes over and gives me a file when she’s ready). Anyway, she pulled up my website to see where we were currently, (yeah, I know – wouldn’t you think she’d be current, checking in every few days?).

Dad! You haven’t posted anything since 2015! People are going to think you’re dead!

I gave her my best hangdog look.

Knock it off! You don’t get to use cancer! That’s history. Over. Time to move on!

I admitted I knew that, but was trying to worm my way out of my complete and utter negligence of the publicity side of my career. She got me to promise to get back to updating, to journaling, to keeping current.

But I didn’t. I thought a lot about it, but I didn’t do it. We lost my younger sister Cindy this year. If you knew Cindy, you’d think it impossible, something as puny as cancer taking her. But cancer’s not puny, and despite strength and courage unimaginable to me, to say nothing of a will way stronger than iron, Cindy is gone. The earth should have cracked at her passing, the universe should have split. But as loss so often is, it was quiet, leaving us all deflated and heartbroken. It’s taken some time for me to regain focus.

I have some vague recollection of posting a while back about habits, and how mine are nearly all bad. And over the past few years, since before 2015, I’ve gotten way out of the habit of posting anything, out of the habit of a lot of things.

So, I’ll catch you up, briefly. See if I can’t get a habit started again. Sometime a while back I was diagnosed with cancer in my vocal chord. If you’ve known me a long time, you’ll remember a voice that could really holler. I was loud. As a child I was asked by innumerable teachers to get everyone’s attention. In high school, the adorable little girls next door, Amy and Julie Hoffman, told their mother they were afraid of my brother Todd and me. They’re so loud, was their explanation. I could stop my dogs in their tracks at 400 yards, occasionally terrifying innocent bystanders (even some not so nearby) in the process. Yeah, that’s gone. But I’m still here. Two surgeries to extract the cancer, two more to rebuild my voice as much as my throat would allow, and then, once I was convinced I was going to live, I had my knee replaced. It would have seemed a waste of money otherwise.

And I lost my mind for a bit. Or more accurately, was kind of lost in it. I was unable to digest a book, paint well, and seemed to have suffered almost a complete loss of my sense of direction. I didn’t even know I had a sense of direction, I was just never really lost, comfortable still when others were sure I (we) was, or might have been, lost. A midnight paddle, for example, and portage and more paddling through the Adirondacks that left my brother-in-law a little fuzzy on how we’d arrived at our campsite. That sort of thing. But after my medical adventures, it was gone, along with the rest. And a few other oddities, skips of perception, etc. Finally after a couple of really strange and disconcerting episodes scared me to the doctor, my GP, my wonderful GP, ran a few tests and confirmed two things-

- The anesthesia required for five surgeries, over so short a period, had been, “a severe insult to my brain”.

- Outside of the cancer, I was insanely healthy. Not healthy like a 55 yr old guy, but maybe 28 to 30. (This is not to claim anything affecting my appearance, which is all of the current 58. Or more).

And the cancer seems to have been dealt with. When will my mind be my own again, I asked. Well, that’s a tough one, he said, (or something along those lines). You need to be active, to sweat a lot, to make your system circulate, and it will come back with time. But there’s really no telling how long it will take. A couple years. Maybe more. So get busy, he said, with life, with living. Don’t think about it.

Hard not to think about. And I’m hard headed. I was raised to work, so I kept painting. Poorly for a long while. They made beautiful flames when they burned.

I went to Alaska and ran a remote river with friends. I walked the dogs. A lot. Exercised. We welcomed an amazing granddaughter into the world. And after the kids gave me permission, I convinced Darby we should move back to the Pacific Northwest of my youth.

And then, seemingly in the blink of an eye, Darby got a job that really excited her, in Portland, OR, my home town. Next thing I knew, she was there working, we bought a house I hadn’t seen other than Zillow, and with the help of friends and family, we packed up a truck, loaded three cats and the White Devil into Darb’s truck, Uly in the cab with Todd and me, and off we went to Oregon City, OR. A trip we all swore we’d never do again, but I knew I had to repeat it a few months later with the rest of our stuff, with my buddy Paul Driscoll along as co-pilot.

Damn. What a pain in the ass. Seriously. But we’re here now, and I love Oregon as much as I did when I was a kid. More for all the years of missing it. The whole place is new to me again, and I hope to explore it until I drop, 35 or 40 years from now. Rivers to run, mountains and coast to hike, and steelhead to chase. At least that’s the plan. I’m not new to the idea of plans going awry, of punches to the head, but I’m making plans anyway.

And granddaughter No. 1 has been joined by a little sister, and a cousin. That’s the downside of the move – them so far away. But it’s actually quicker to fly back and see them than the drive was. And I don’t have to drive through New Jersey traffic. And the other part of this plan is grandma and grandpa’s ultimate summer camp. Hiking, horses, rivers, rafting, paddling, ocean…. they’re not going to want to go home. And until they get out here, or if they don’t, we’ll be back there frequently.

So out of the blue, I get a call the other day. I didn’t recognize the number, and didn’t answer. But there was a message, and it’s from an old fishing buddy- like way back old, college days. I call him back, we catch up a little, and he said, Yeah, I was on your website, and I saw that you hadn’t posted since June of 2015. I was afraid you were dead.

So this is the first attempt at re-establishing the habit. To let you all know, I’m not dead. There are a few updates tucked in here, on the Artist Statement page. And the painting above. I’ve been working a lot, with a bunch of pieces finally coming together. More soon. I think. If not, Emily, give me a swift kick this time. I can’t have anyone else thinking I’m gone.

ps- (do blog posts have ps’s?)- This spring, something has cleared out more of the cobwebs. I suddenly have more ideas than I can keep track of. Like it was pre-cancer. I have some summer travel in between, but I’ve got to find a larger studio this fall. So much to do. Big stuff. Stuff I’m really excited about. I’ll try to remember to keep you all in the loop.

So, if you’ve read this far, I need to say Ive migrated the Field Notes to my new website- the one I got scolded for not updating. I’ll post here a few more times, but at some point it will all be over there. It can be found at: http://www.richardcharrington.com/field-notes/

October 2nd, 2017 by dave dorsey

It’s tin man hands. And it’s a good look. If Goldfinger had been named after a different precious metal, his victims might have had this kind of shine, only all-over. These are Mandi Antonucci‘s fingers, after kneading a lump of graphite putty to coat them thoroughly enough to do some experimental finger-drawing. Her drawings, which employ some of the techniques of optical illusion Escher used, seem to be more Jungian snapshots of her psychic history and personal struggles than his cerebral studies in recursive visual structures. One of her psychological self-portraits is endearingly entitled Daydream Believer, in a nod to The Monkees, beloved by her mother who turned Antonucci into a devotee as well, after overhearing Davy Jones sing his tunes to those Wrecking Crew arrangements so many times. Her interesting, accomplished work can be seen now at Maker’s Gallery.

It’s tin man hands. And it’s a good look. If Goldfinger had been named after a different precious metal, his victims might have had this kind of shine, only all-over. These are Mandi Antonucci‘s fingers, after kneading a lump of graphite putty to coat them thoroughly enough to do some experimental finger-drawing. Her drawings, which employ some of the techniques of optical illusion Escher used, seem to be more Jungian snapshots of her psychic history and personal struggles than his cerebral studies in recursive visual structures. One of her psychological self-portraits is endearingly entitled Daydream Believer, in a nod to The Monkees, beloved by her mother who turned Antonucci into a devotee as well, after overhearing Davy Jones sing his tunes to those Wrecking Crew arrangements so many times. Her interesting, accomplished work can be seen now at Maker’s Gallery.

It’s tin man hands. And it’s a good look. If Goldfinger had been named after a different precious metal, his victims might have had this kind of shine, only all-over. These are

It’s tin man hands. And it’s a good look. If Goldfinger had been named after a different precious metal, his victims might have had this kind of shine, only all-over. These are