November 27th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Cezanne’s studio, courtesy Paris Review/Joel Meyerowitz

Joel Meyerowitz makes some excellent observations about what he noticed when he saw color of the walls in Cezanne’s studio and how that color’s fluid properties, as the background for whatever Cezanne observed in his still life paintings, helped give birth to modernism. Delightful. It’s also wonderful to recognize the little sculpted Cupid still there, so familiar from Cezanne’s painting of it. Here’s an except from the fine little essay, which is actually itself an excerpt from Meyerowitz’s new book, Cezanne’s Objects:

Cézanne painted his studio walls a dark gray with a hint of green. Every object in the studio, illuminated by a vast north window, seemed to be absorbed into the gray of this background. There were no telltale reflections around the edges of the objects to separate them from the background itself, as there would have been had the wall been painted white. Therefore, I could see how Cézanne, making his small, patch-like brush marks, might have moved his gaze from object to background, and back again to the objects, without the familiar intervention of the illusion of space. Cézanne’s was the first voice of “flatness,” the first statement of the modern idea that a painting was simply paint on a flat canvas, nothing more, and the environment he made served this idea. The play of light on this particular tone of gray was a precisely keyed background hum that allowed a new exchange between, say, the red of an apple and the equal value of the gray background. It was a proposal of tonal nearness that welcomed the idea of flatness.

November 24th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Jordan Peterson

Below are excerpts from two recent conversations with Jordan Peterson, a professor of psychology at the University of Toronto. Intellectually, he is following a path laid out by Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell in an attempt to draw psychological truths from the wisdom traditions, otherwise known as major religions (before our culture turned the word “religion” into a political slur and before everything had to be interpreted politically). Peterson moves beyond that in the second conversation, which ought to be of particular interest to artists. I find his thoughts on this subject compelling because I think religious faith draws its vitality from non-conscious wellsprings, just as great art does—faith and creativity both attempt to tap into a larger mind, a larger awareness, than the ego-centric, rational consciousness with its attempt to grip the reins and remain in the saddle of daily experience. For most of my adult life, I would say I’ve been totally in agreement with what Peterson says here, and yet as I get older I worry about an unquestioning embrace of “meaning”. What he says about the fundamental need for meaning is absolutely true, though I think it’s missing an acknowledgement that it ought to be hedged with hesitancy and caution. (Maybe I can venture reluctantly into that in the next post. This subject is pushing me, again, to make sense of why I paint and to question whether or not it adds up, which makes me uncomfortably curious.)

The craving for meaning is fundamental, maybe more fundamental than the instinct to survive itself. It may, at least, be indispensable to that instinct, as Victor Frankl suggested in his account of his time as a prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp, where prisoners who had no framework of meaning died much more readily than those who had a way to make sense of their suffering. I think Donald Kuspit is pointing toward this in much of his published criticism by positing eros, desire, as fundamental in the production of art, and there is definitely an erotic element in nothing more than the energy of oil paint applied to canvas in a certain way. Eros is the affirmation of life over death; so by definition art is erotic. But he means more than that: he means MORE

November 20th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Sometime This Winter, Bill Judkin, 36 x 36, acrylic, dye, plaster compound

The Patricia O’Keefe Gallery at St. John Fisher College is exhibiting Bill Judkins paintings from Nov. 13-Jan. 5. This one’s a beauty.

November 17th, 2017 by dave dorsey

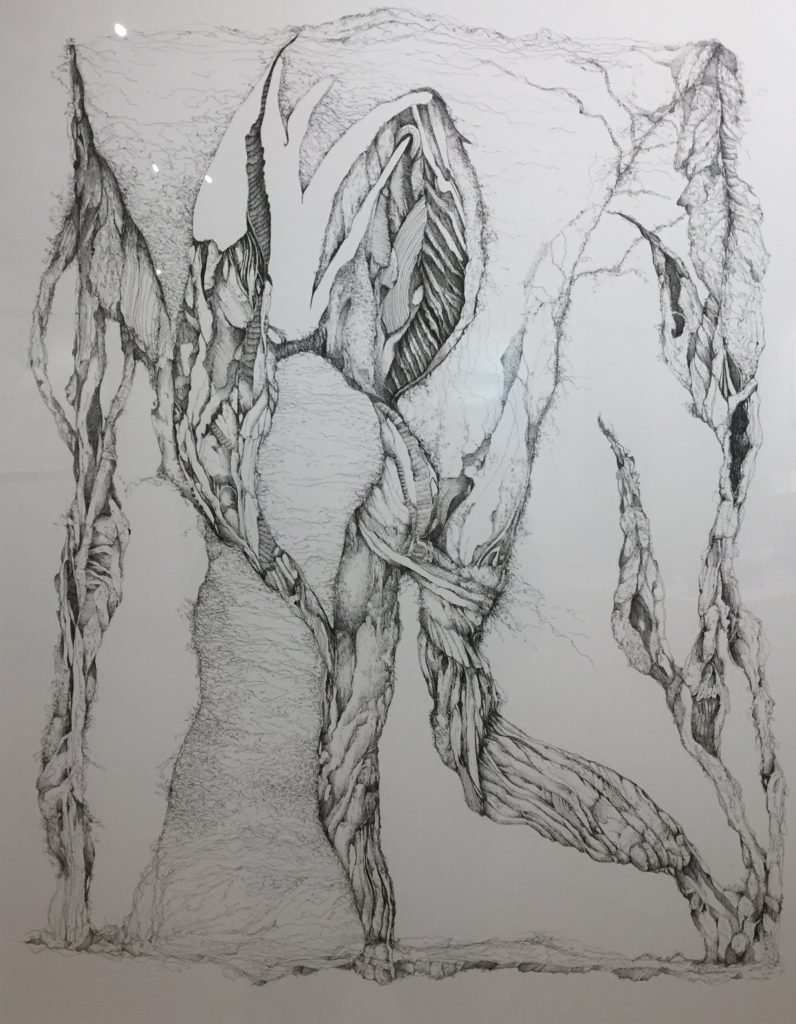

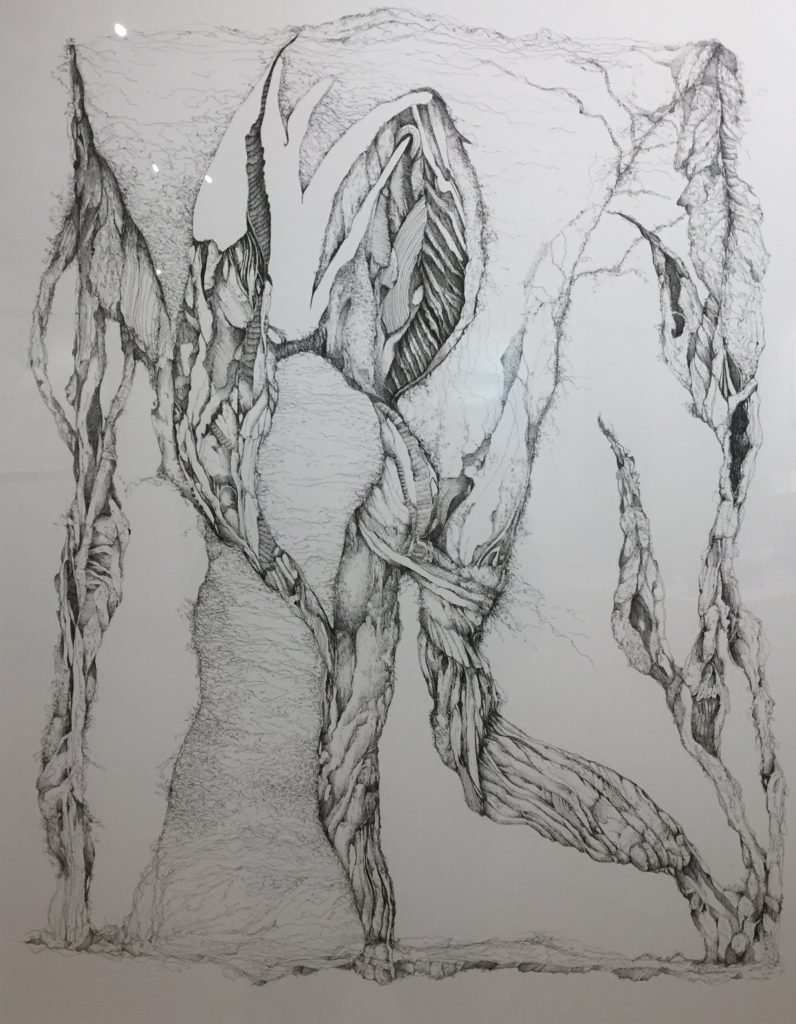

Three Seekers, Bill Stephens, 36 x 28, pen on paper

New drawings from Bill Stephens are on view at the Patricia O’Keefe Ross Gallery at St. John Fisher College. It’s another chance to see some of his work, maybe best described as subliminally generated. Some of his figures and forms seem to be animal, vegetable and mineral all at once. They never just sit there. His colored drawings are getting more and more interesting and one recent one in his Instagram feed is a knockout. Show runs from Nov. 17-Jan. 5.

November 12th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Matriarch

I met with Jean Stephens this week to talk with her about her new exhibition at Oxford Gallery, Continuum. I’d been impressed by her previous solo exhibition at St. John Fisher college, and I wanted to hear her thoughts on how her work has evolved since then. She paints landscapes and artifacts she brings back from her immersions in nature: a deer skull, eggs, nests, and rocks. She and her husband Bill are complementary souls, both spiritually-oriented without being attached to any particular creed or religious practice, though Bill regularly meditates. Both do work that is largely an attempt to tap into the subconscious, in Jean’s case with more emphasis on rendering the outward appearance of the world around her. What struck me in most in the new show—and in examples included in a concurrent exhibit at Main Street Arts—is a series of paintings of eroded rock towers she saw on a trip two years ago to the Southwest. She felt surprisingly at home in the rough-hewn landscape at Arches National Park and that encounter became a catalyst for a new kind of painting. We talked about her work in general and this new series of improvisational geological figures she’s been developing.

I began by asking about two of her paintings in this show that I’d seen in the earlier exhibit in which she takes rocks, sticks, bark and other objects she collects from nature and arranges them in the shape of human figures.

You had these in the St. John Fisher exhibition.

Yes.

You talked before about their spiritual significance to you.

They’re spirit guides. When I started gathering the items to set up the still lifes, the figures just appeared. I started putting things together. That wasn’t my intention. I just let it happen. I feel a spirit comes through me and helps me with the work.

Bill sees his work as well as a spiritual activity as well.

It’s not surprising that things overlap. We’ll start looking like each other eventually.

Where did you collect the objects for these paintings?

Walks in the wood. On the shore of Maine. How many people have boxes of rocks in their studios?

The birch bark is from the bed in our driveway circle.

You collect these things without any idea what you will do with them.

The backgrounds . . . the one with the corn husk and the egg is a piece of wood from an old gun cabinet that a student gave me. This other is part of the bridge support on Route 65. All this wonderful graffiti. Bill and I were taking a walk and I took a photograph of it. I printed it out on a large sheet of drawing paper.

<We moved over to another still life combining a shell with a page of writing superimposed across the surface of the painting, something she’s been doing in other work as well.>

This one is a page from my great grandmother’s autograph book. Her name was Henrietta. These were the sentiments that people wrote in these books. Tender, sweet, sometimes poetic. In those days people had these books. There are little stickers in there. Some of the comments allude to the man she was going to marry. She died young in childbirth. It’s a treasure to have this little part of history.

<We moved to an oil on panel painting of a Robin’s nest with long trailing tendrils, almost jellyfish-style.>

What kind of nest is this?

We had a robin build a nest from a grapevine wreath in our back yard. And when they were done, doves came in and added a couple twigs and used it themselves.

You usually work in oil.

Oil, colored pencils and graphite.

The landscapes are before or after the workshop you did?

After.

Tell me about the workshop.

Timothy Hawkesworth. Irish guy. In Pennsylvania on a farm. Three sisters run the farm. Christmas trees and maple syrup. There’s sheep, chickens. Eastern Pennsylvania. You could go for a two-week commitment, or one week. You get a room to stay in. They feed you three amazing organic meals a day. Tim does a talk every morning. He reads poetry. A lot of it is closing the gap between you and the work. How do you get into the painting? What is your energy approaching the work? Bill and I had just come back from the Southwest. I had two days to do laundry and repack. All those Southwest forms, all that color, all that heat, was still in there, ready to come out. We did the four corners. Moab, Arches, Canyonland, Dead Horse Valley, ended up in Santa Fe and flew out of Albequerque. I had packed a ton of supplies and had no idea what I was going to do (in the workshop). This was two summers ago. I started with drawing, just some gestural line work to get my feet wet. Tim did some demo stuff and came to me one morning and said, “Let me show you something.” I had oils and Liquin and paper and he took something I’d started and just went wild. Whoa. That was starting to crack the door open for me. I’m here, but let’s take some risks. The studio I started in I had a hard time because of all the hay. The sheep were right next to me and I was having trouble breathing. So when there was a change of people it opened up and they moved me to a better space. There was a morning I had a breakdown and a breakthrough. He started by asking the group, “Who was excited when you were born? Who was disappointed when you were born?” I was the third girl in our family and my father was just waiting for that son. So I mean I just spent twenty minutes in tears. He came by with his co-facilitator and asked, “How you doing?” I shared some of my journey. They were amazing. I felt as if I had this big support.

What was he doing by asking that?

It was part of his morning talk. He would talk about work; he mentioned Philip Guston a lot. He likes his work. And I’m not sure how he got to that question. It just hit me. It was what I needed to hear.

It sounds as if he was trying to get you connected to deeper motivations.

Who’s in here? How does that come out? His facilitator said, “We need to bring little Jean out to play. Jean needs to play.” Because I’m pretty tight and controlled.

We’re all dealing with that. I talked about that with Chris. We’re always trying to balance doing what we know how to do while taking chances.

Is that OK? Is that legitimate art?

That drawing that Rembrandt did, the little ink sketch of the mother with child, the baby trying to walk, like a calligrapher he created this figure that is full of energy and it blew Hockney away. I think it’s what you’re talking about.

It’s what we did as kids. What shut that spontaneity down? The what-will-people-think business. It’s OK, Jean.

How far were you into the workshop?

Halfway, at least. It wasn’t until I got into the second week that these started to appear (the towers from Arches park.) These were done there.

They stand out.

The writing was automatic writing.

That’s how it looks.

<She depicts these pillars of sandstone or other rock against lines that appear to be legible writing from a distance, but are simply script-like marks.>

I work with my non-dominant hand, they’re just gestures. It’s informed by the writing from my great grandmother’s book. Being out west, we saw a lot of petroglyphs. The native people out there, this was their form of writing. And we aren’t writing by hand anymore. No penmanship.

No penmanship for me, for sure.

Our sense of history as human beings, writing to each other, is eroding away. (Like the rock towers.)

The line for its own sake, the shape and energy of the line, freed from its need to mean something else. What do you call these?

They spoke to me as figurative, matriarchal. The one on the back wall I call grandmother. They are feminine, powerful. The spirit out there, the native spirit and the land spirit, is very strong.

There’s a tremendous energy in the desert and the mountains.

The earth is exposed in a way that it’s not exposed here. You’re looking at layers of millions of years. Out there, I’m face to face with it. It surprised me because I love the landscape around here.

The west is really different.

How I worked the piece, there’s that sense of erosion, history, the writing again is behind and then across the figure on the lower part. Appearing and disappearing as it wears away. That’s oil on Arches paper used for oil. I pinned a whole bunch of it up on a wall and just went at it with paint.

Just the feel of the paint is so nice. I love the color.

This is the matriarch. The lines are colored pencil. It’s got me a little freaked out because I love doing that, but I also love doing this. I’ve been playing with encaustic now too. It’s different. You work with the hot paint and it does different things. You get texture and surfaces that are unexpected which reminds me of printmaking.

These lines remind me of Gorky. You’re working from the same place as the surrealists and abstract expressionists: the subconscious.

I did the calligraphy first so that’s underneath informing the paint. Some of it gets obscured. Some remains.

That’s cool. There’s a counterpoint between the drawings and the paint. The lines don’t dictate what you’re going to do with the paint.

In the pyramid piece I covered it up.

That’s a more exacting image. The paint in these, though, has the same feel of your hand as the drawing.

I didn’t intend it to be a human figure. But she’s there. She’s in me and needing to come out in this way. I can’t fight it anymore. I’ve been afraid of her too long. I spent two weeks in Hawaii in September. I went with my best friend. The color and the fire; I did a couple watercolors to respond to them. But here probably should be some larger oils maybe on piper.

The encaustic seems like a medium more suited to it. You’re drawn to these elemental things.

I was always outside playing in the fields and the trees as a kid. That’s why I’ve been on this journey in organic form: nests and eggs and landscape.

What is your background in terms of your sense of spirituality?

I think I’m a naturist. The spirit comes through nature, the sky, the stars, the spirit of the land. I was raised Wesleyan Methodist, and it was brutal. I had an opportunity a number of years ago to participate in a vision quest for a fourteen-hour stretch. Spiritual, personal growth, at a retreat center south of Ithaca. One of the final events was this vision quest. We went out when the sun rose and came in when the sun set, no speaking, on your own. We were just asked to notice what was going on in the natural world. I saw a lot of things with wings that day. I saw a hawk just soaring, gliding, and just tipping a wing or its tail, letting go. It was a great metaphor for life.

He was just riding the wind.

That was my message.

November 7th, 2017 by dave dorsey

In conjunction with Oxford Gallery’s show of new work by Chris Baker and Jean Stephens, Continuum, I drove to Weedsport and met with Chris at his home studio for a conversation about his work. Here are some of his comments when he could get a word in edgewise, despite my motor mouth. Chris is super-fit and in September he finished eighth in the world for his classification in Rotterdam’s ITU World Triathlon Grand Final):

Tell me how you got started.

When I was in high school it was for fun. Always enjoyed it. But then when I went to Rochester Institute of Technology for undergraduate work and things started to meld. I wanted to do it, become a professional artist, but realistically . . . you have to have a plan B, or maybe painting is the Plan B. I was lucky enough that I just went for a BFA and when I got out in ‘68 the war was on, and someone said, “If you go into teaching you’re draft-free.” I went into teaching, but it didn’t work. I taught in Auburn for two years. After two years in the service, I got back out, went right to Auburn and got an MFA and again thought I want to paint not teach, but I had to go back into it. In Auburn, they said no openings but there’s an opening in Cato. They hired me when I walked in the door. The superintendent said you’ve got to get your certification. He said “Let me just check, you’ve had two years experience in Auburn” So I got my certification a month later in the mail. Thirty-six years there. That was a great job. Summers off, painted all summer. Over the years I taught kindergarten all the way up to a little bit of college in Auburn.

That’s the great thing about teaching. It really does afford almost enough time to make art.

When we lived in the village we had a carriage house I converted into a studio. I was able to work evenings, weekends, year round.

What sort of work were you doing then?

I started playing around with tempera paints in the classroom.

On the way to gouache.

I went to Commercial Art and said this Crayola tempera, as much as I enjoy it, not sure . . . they said try gouache and that was that.

You were doing representational art even back then?

MORE