January 31st, 2018 by dave dorsey

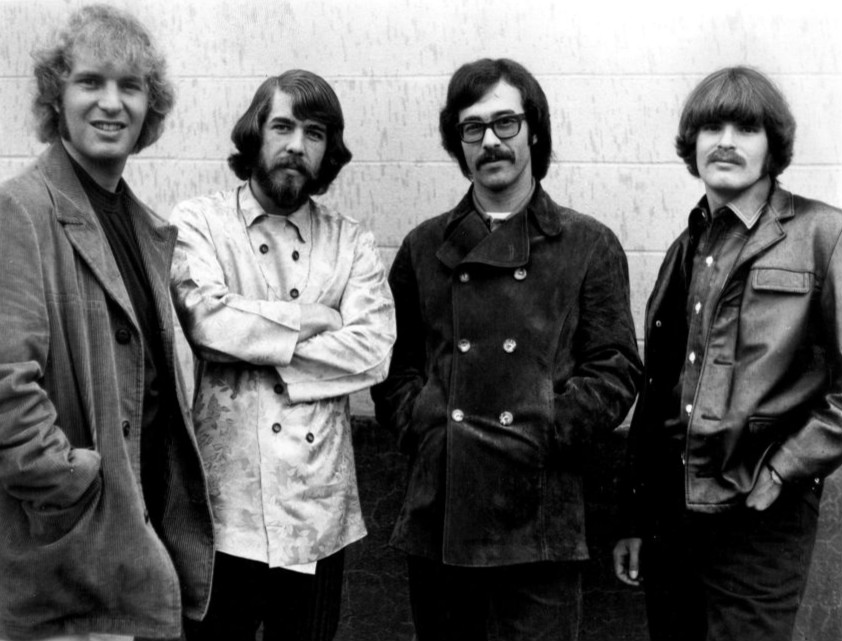

Wayne Williams, left, and Tom Insalaco at their new gallery space circa 1973

At 2 p.m., on Feb. 1, Tom Insalaco and Wayne Williams are going to talk about making art over the past half century in an anniversary event at Finger Lakes Community College. The discussion will be held in the campus gallery named after them. It should be interesting, because they’re both distinctive characters with an independent and occasionally refreshing, iconoclastic view of the art world today. It would be worth attending even if they talked about nothing but the ways in which things have changed for artists since these two began thinking seriously about art more than fifty years ago. The photograph above was taken at their gallery space at 34 S. Main St., in Canandaigua, NY. Barron Naegel will moderate the conversation as part of a larger celebration of the college’s 50th Anniversary. The school opened its first classes on Feb. 1, 1968 as Community College of the Finger Lakes.

Other celebrations of the school’s birthday will include a time capsule to be buried in May and dug up in 2068, and a 124-page commemorative book “This Bold Decision: The Story of Finger Lakes Community College.” The discussion at Williams-Insalaco Gallery 34 will inaugurate an exhibit of work by professors and their students: “Mentors and Mentees: Celebrating 50 Years.”

The show will include work by Insalaco, Williams—both of whom are now retired—as well as work by Rand Darrow, Jeff Feinen, Peter Gerbic, John Lord, Don McWilliams, Bill Santelli, Jean Stephens and Debra Stewart.

Call 585-785-1623 or visit give.flcc.edu for information.

January 26th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Anamorph, Jason Ferguson

I’m pleased to be able to point to a couple fine honors that Manifest Gallery bestowed on me late last year. I haven’t gotten to posting about this yet in detail because I’ve been immersed in the tunnel of labor required for the paintings I’m going to show in March at Oxford Gallery. Even with marathon painting sessions, the crop of new paintings looks very thin indeed for the sum total of new work since my show in 2015. (A couple non-painting projects stole probably a third of my time in that period, which hopefully is the last time I’ll need to pull myself away from painting to that degree.) But I think my efforts were rewarded well in at least some of these pieces. One of them in particular is the most successful painting I’ve ever done, in terms of exhibition history, awards and now a sale, prior to the show: Breakfast with Golden Raspberries. It’s the reason for one of the honors Manifest sent my way.

First of all, my work was included in Manifest Gallery’s 8th International Painting Annual. For fourteen years, this non-profit in Cincinnati has operated as a hub for artists around the world, enabling them to exhibit without regard for the vagaries of the art market and trends in critical theory about what’s worthy in art. Its jurors are volunteer experts in art and design from across the United States, including professors, working artists, curators, gallery directors, and others qualified and trusted to provide sound objective judgment of the works provided. They cull through a flood of entries for each show and publication the gallery sponsors, winnowing entries down to the fraction it will include—the process is tough, meaning for even very good artists the opportunities are narrow. There’s a wealth of masterful work being done, and too few ways to get it seen and purchased, at least until the Internet eventually lives up to his promise. In the meantime, Manifest serves an almost unique function, and is held in high regard by nearly everyone I know in the art community.

Its 8th annual received 1301 entries, from nearly 400 artists, working in eight countries. The book will include 101 works by 59 of those artists. I haven’t been alerted yet about which of my entries, or which one, was picked.

The second honor was more unusual and represents a new prize offered by the gallery: being selected as a finalist for The Annual Manifest Grand Jury Prize. Jason Ferguson’s Anamorph won the $2,500 prize, a self-portrait of sorts, a 3D printed plastic sculpture derived from CT scans of the artist’s own skull, originally featured in Manifest’s exhibition SCHEMA. My painting was among 40 works by 38 artists chosen as a finalist from a pool of 8,453 separate works submitted for consideration to be included in 20 group and 10 solo exhibitions during the gallery’s 13th season. For this prize, the Manifest organization created a competitive winnowing process to select the best single work out of everything exhibited at the gallery throughout the previous year. Here’s what Manifest announced:

Starting with our 13th season, Manifest has launched a new annual cash award of $2500. The Annual Manifest Grand Jury Prize is a seasonal capstone recognition awarded to one work from among all those exhibited on-site at the gallery across the season. The first Grand Jury Prize is currently considering works exhibited at Manifest from late September 2016 through mid-September 2017.

The jurying process was conducted ‘blind’ without reference to the artist’s personal info, location, or background. Each jury usually consists of at least 5 jurors, and sometimes more than 10. Jury groups are shuffled and changed from exhibit to exhibit, so a pattern does not result. (Learn more about the Manifest jury process here.)

The Manifest Grand Jury Prize will be re-juried by the same advisors who served across the season, excluding any who may have a conflict of interest. When concluded we anticipate that this will result in 20-30 individuals having scored the works shown below in an effort to determine the winner. Learn more about the Manifest Grand Jury Prize here.

At least one work per exhibition is included for consideration. Solo exhibitors are invited to select their preferred work from their exhibition for jury, or may defer to the Director’s choice.

All told, season 13 presented 469 works by 279 artists in 41 states and 10 countries. Details on the exhibitions, and all of season 13, can found at this link. The entire season, and all works shown, will be documented in the forthcoming Manifest Exhibition Annual publication by around spring of 2019.

Thumbnails here may be clicked to see the full image.

January 23rd, 2018 by dave dorsey

I’m listening to Jordan Peterson’s lecture series where he approaches the Old Testament as a psychologist and phenomenologist: he reads the work as Jung would have, as an explication of structures that underlie human nature and the psyche. He speaks for nearly three hours in the first of the series and never gets to the first line of Genesis—his brain is like Kafka’s, bursting with a world that just wants out of his head. Peterson is approaching the whole subject as a rationalist, a scientist trying to understand patterns, examining the text for whatever it conveys with his reason, accepting nothing on faith, without ruling out that there may be much of value in the book that reason can’t plumb.

I’m listening to Jordan Peterson’s lecture series where he approaches the Old Testament as a psychologist and phenomenologist: he reads the work as Jung would have, as an explication of structures that underlie human nature and the psyche. He speaks for nearly three hours in the first of the series and never gets to the first line of Genesis—his brain is like Kafka’s, bursting with a world that just wants out of his head. Peterson is approaching the whole subject as a rationalist, a scientist trying to understand patterns, examining the text for whatever it conveys with his reason, accepting nothing on faith, without ruling out that there may be much of value in the book that reason can’t plumb.

He takes one last question from his audience in the first video, and it has to do with painting. I think the questioner here is suggesting a reproduction of an original painting in some three dimensional form, not a photographic reproduction—some kind of 3D printed version of a work where the paint is duplicated in all its depth. It’s possible to imagine this as an effective way to copy a painting, up to a point. But the surface of even the most organized painting is full of serendipitous chaos, where the substances, the paint and oil, are mixed and applied in the most unpredictable ways, even following the strictest methods. At many levels an artist’s own “copy” of a previous painting wouldn’t be remotely identical to the original, even though the image is mostly the same. I’ve done this myself, painting two versions of a pie tin brimming with blueberries, and they are easily recognized as essentially the same image but are quite visibly different, in multiple ways.

Peterson also talks about historical context, but such an abstract concept seems to veer away from what his friend spoke about: how a painting is an artifact in which the time required to make it becomes evident in the physical features of the painting. Yet historical context for Peterson means the context of human history itself, and he points out how cognitive function follows physical adaptation to the world, grows out of it, not the other way around—in both evolution and in individual perception—and so maybe they are talking about the same thing, in a way. You can feel the time invested in the painting, by the artist—as Peterson says—in the layering of paint. Subconsciously, you sense ways in which the paint betrays to the viewer how much the artist kept going back, or not going back, to certain areas, with new applications of paint, and you feel both the effort and the mastery of the process in an instant, just by looking at the work. All of which makes the work radiate a quality that actually makes time itself visible—as songs so easily make time audible. Not time as in tempo, but the vast sense of past time, as well as the aura of possibility, the depth of the future—and with some concerts, an immersion in nothing but the immediate present.

In the same way, paintings embody the person of the artist in ways that can’t be controlled by the artist—every painting is an involuntary confession of character and personality and the artist’s entire world.

Question: You were in this one room in a museum in New York looking at this one work, a Renaissance masterpiece, and these are generally accepted as amazing artifacts. Does an original work of art, as opposed to a high fidelity reproduction, contain the spirit of the artist who created it and does this account for the disparity in how much you have to pay for it . . .

Peterson: It does in part. I know a good portrait artist. One of the things he pointed out about a great portrait is that it actually contains time. A photograph is one instant. But a portrait is you layered on you layered on you. It has a thickness. It’s a direct manifestation of that creative act of perception. There’s more to it than that. A painting doesn’t end with the frame. We tend to think of a painting as an object but most objects are densely (infused?) with historical context.

Question: If you have a reproduction of a painting that is exactly the same at the level of detail, why would you want the painting?

P: It’s exactly the same at the level of detail but not the level of context.

January 20th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Michael Dorman in Patriot

When I put the last mark on a painting, it’s almost never what I expected it to be during the first brushstroke. And I’m usually surprised several dozen times while getting from start to finish by what I’m required to do. So I can identify a bit with the protagonist in Amazon’s original series, Patriot. It’s a funny, poignant, and whimsically Kafkaesque series built around the personality of a sad-sack folk singer whose day job is working in Special Ops for the CIA. Actually, he has two day jobs. The other is his NOC, his non-official cover, as an industrial engineer working in a bleak Rust Belt factory in Milwaukee where he specializes in the “structural dynamics of flow.” In layman’s terms: piping. His company, McMillan, builds conduits for anything and everything, creating perfect circles in a world of epic imperfection, both planetary and human. These indispensable imperfections are what drive the story forward through one entertaining absurdity after another.

The theme of the show is “the structural dynamics of flow,” the principles of moving anything from Point A to Point B, that could apply to both McMillan piping and counter-intelligence. Likewise, Lakeman, with the help of his family and a co-worker, attempts to get $11 million Euros through airport security into Amsterdam and then on its way to Iran via a courier in Luxembourg. (His family cohort includes Cool Rick, Lakeman’s Beastie Boys-obsessed brother, and his father, who presides over most of the action as a seasoned but compassionate “control” who is professionally imperiled by his son’s mistakes.)

Nothing and no one in the show gets from Point A to Point B as planned. McMillan is going bankrupt. The covert payoff is making the rounds of Luxembourg as more MORE

January 7th, 2018 by dave dorsey

He who would do good to another must do it in Minute Particulars.

General Good is the plea of the scoundrel, hypocrite, and flatterer;

For Art and Science cannot exist but in minutely organized Particulars,

And not in generalizing Demonstrations of the Rational Power . . .

-William Blake

In the passage below, I think Jeff Blehar’s question was getting at something crucial when it comes to any art. It was from a podcast in which three political journalists took off their current affairs hats and spent some time talking about what they really love—music. In particular, Blehar was marveling at the sound of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Green River. He’s really speaking about all the tiny incremental “minute particulars” that go into any band’s unique mature sound. I was struck by his comment because I had a similar thought listening to “Bootleg,” the second song on another of the band’s albums, where, when the bass comes in, suddenly their sound surfaces—an illusion of looseness, the casual way the four instruments seem to lope along, in no great rush to get the job done, and come together as if by accident, two of them riding on the bus just jamming, waiting for the bus to stop and pick up the other two. The way its elements converge make any great work of art unique and individual in a way that’s impossible to duplicate or even describe clearly—and I don’t think it’s something that could be translated into a set of reliable algorithms. In other words you can’t learn how to do it repeatedly—you end up imitating pieces and parts, but not the whole. You can copy a Vermeer, but it won’t be a Vermeer. The jury will be out for a while on whether a computer could create a convincing Vermeer forgery, but I doubt that it ever will. Blehar says:

This is one of the things that gets lost but you hear it in everything they did. It’s that sound. Green River is the best embodiment of the band’s sound. That sound . . . every time they could just walk in and create a song that sounded good, like ear candy, something about the way Fogerty’s guitar, and his brother’s rhythm guitar and the bass and the drums came together on an elemental level is fundamentally satisfying. I guess I’ve never understood why nobody else can reproduce this. Why doesn’t every band try to sound like CCR on Green River? It shouldn’t be hard to do in theory. This is not Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It’s four guys in a room. There isn’t even much over dubbing. But nobody has ever sounded like that. It’s such a remarkable achievement. And it gets neglected because you don’t even notice it. They are so good at it, they draw you away from one of their primary virtues by making it seem so effortless.

What’s distinctive is how minimal CCR kept things, like the earlier Spoon, the simplicity in their production and instrumentation, but I don’t think any of that was a conscious choice. After ten years of work, the band had a perfectly realized style—in Susan Sontag’s sense of MORE

I’m listening to

I’m listening to