Archive for March, 2019

March 30th, 2019 by dave dorsey

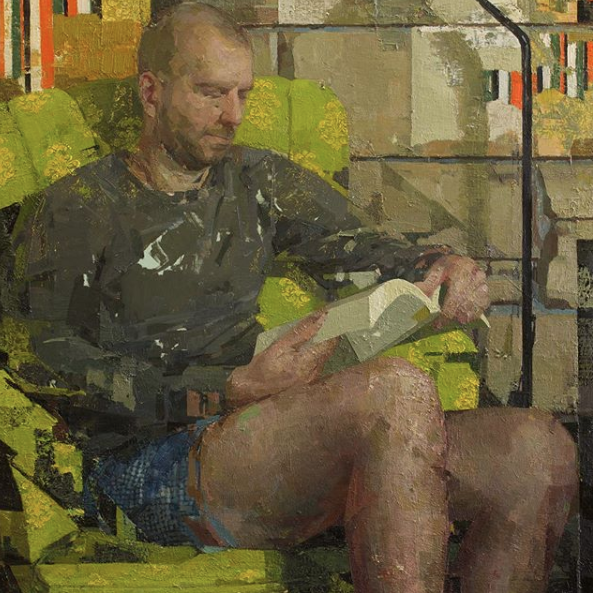

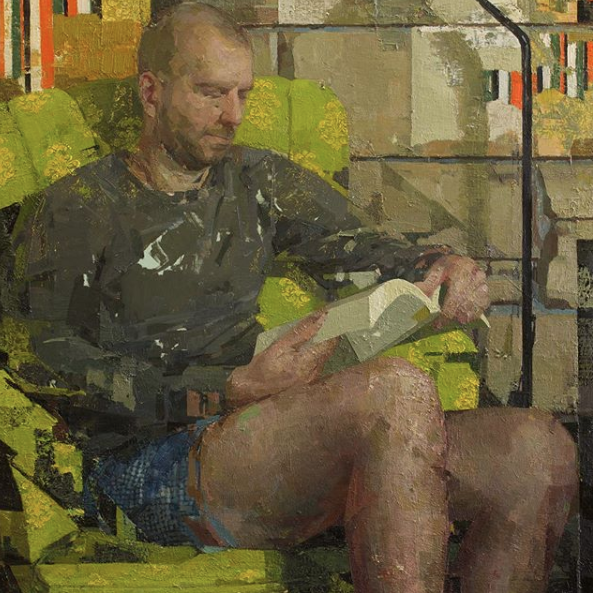

Peter Reading, oil on panel, 36″ x 36″

Zoey Frank has a show at Gallery Mokum in Amsterdam opening on March 16. She has to be the perceptual painter who has risen to prominence more rapidly than anyone else in that club. I’ve been following her with bemused fascination since she was the star of Manifest’s INPA not long ago. She’s everywhere, it seems. When I checked out Arcadia’s booth at the L.A. Art Show two years ago, I noticed they had one of her paintings on view. She’s included in a group show now at Danese Corey, with plenty of work to spare for a solo show in Europe. For someone with her prolific confidence, the challenge has to be picking what not to paint.

The polarities in her work are what keep me trying to reverse engineer what she’s doing, but it’s as hopeless as twisting a Rubik’s Cube back to perfect alignment. At her best, the surface works on its own semi-abstract terms. Conversely, the image works just as well, as a representation, despite all the flat decorative patterns she so often seems to improvise behind and almost in front of her subject, if you can actually pin down a single subject in some of them. Note the checkered pattern of the boxer shorts, the irregular cinder-block lines in the wall, the random-looking orange stripes at the top, as if someone has ripped a pasted advertisement away. Hers are “all over” paintings that resolve themselves, at least partly into the old familiar genres of interior, figure and still life. When this polarity between surface and image is strongest, but without marks that don’t seem unified into a recognizable image, her paintings are the most satisfying. (It looks as if lately she’s moving more toward heavy impasto, in the vein of Stanley Lewis, and the image flattens into two-dimensional patterns completely, losing some of her charm in the process.) Her work is about the texture of the paint and yet they often look as accurate in the way they convey light as a photograph. (It’s hard to imagine she doesn’t refer to photographs at all in some paintings.) As with most of the perceptual painters, she’s willing to paint anything she sees, seemingly just as she finds it, so that anything for her is a fitting subject. Each individual painting looks more like an inconclusive portion of a long scroll of work that never ends–just an arbitrary clip from a continuous experimental translation of seeing into paint, never quite arriving at completion, which adds to the transitory quality of her images. They feel more dreamed than seen.

In her most interesting work, she’s constantly juxtaposing scumbled or scraped spots of paint against crisply defined edges–the way Eve Mansdorf once talked about the importance of edges as a counterpoint for her more improvisational areas of paint. The governing greenish light here–is it a yellow incandescence or a muted natural glow on her friend’s nose from a leafy summer scene outside? She conceals a line that looks as if she’s trying to slice her friend’s anatomy off at the knees, angling up from the lower right, the way a Cubist would, arbitrarily (hints of Braque often are absorbed into her compositions and texture) and yet that little edge seems to work as an accidental but accurate alignment of shadow. In most of her work, she uses these structural straight lines, as if she’s clicking everything into a purely imaginary grid that keeps surfacing in the shapes she puts down. She breaks up this particular image with little shards, wedges and shims of color, without detracting from the depth of her forms and the realistic light, so that a lot of these details don’t coalesce the way you would expect them to, yet don’t keep you from seeing the scene. In this case, it’s almost the way a digital photograph looks when it’s pulled off a slightly damaged SATA hard drive, fractured with visual noise, but still recognizable.

March 27th, 2019 by dave dorsey

From “Art is Dead; Long Live Aesthetic Management:”

“The work of art,” Alfred North Whitehead writes, “is a message from the Unseen,” or as I would say, the unconscious. “It unlooses the depths of feeling from behind a frontier where the precision of consciousness fails.” This, I think, is the credo and intention of all true artistic creativity–to reach into the unseen depths of the psyche and bring back the pearl of original feeling from them. T.W. Adorno says something similar. “Works of art,” he writes, “do not, in the psychological sense, repress contents of consciousness. Rather, through expression they help raise into consciousness diffuse and forgotten experiences without ‘rationalizing’ them.”

Artistic expression thus undermines the pseudo-self and restores the original self. It uses unconscious feeling to undermine conscious reason. Diffuse feeling arises spontaneously, as though experienced for the first time or suddenly remembered, and so all the more meaningful. It is an unexpected message from the unknown depths, a surprise that cannot readily be explained, which makes it all the more resonant and urgent and profound–and makes the art that mediates it convincing.

–Donald Kuspit, Redeeming Art: Critical Reveries

March 24th, 2019 by dave dorsey

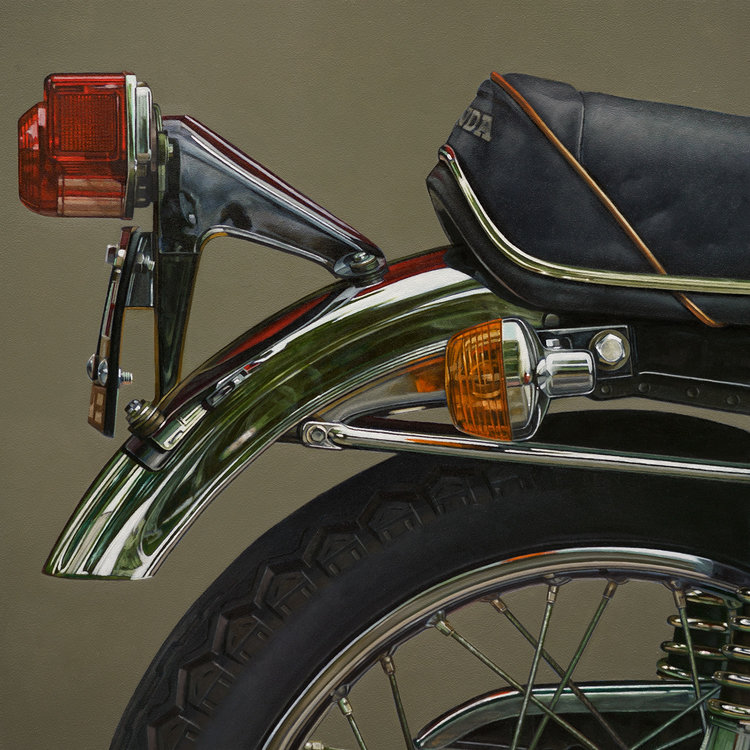

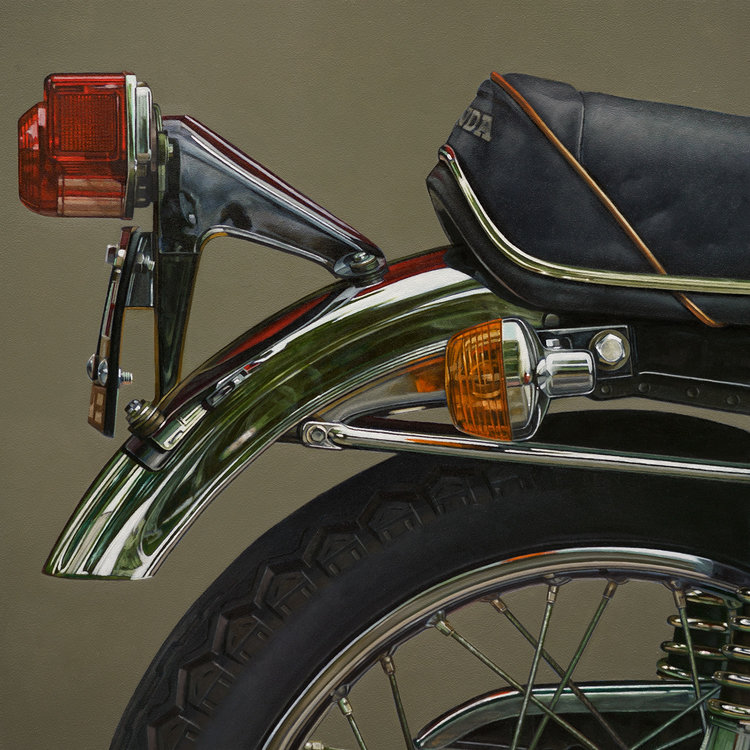

Honda: Aft, James Neil Hollingsworth, oil on panel, 12″ x 12″

To the prejudiced, everything that belongs to a certain category tends to look alike. Likewise, to its detractors, I suspect photorealism all looks the same. In their view, it smothers individuality. It’s impersonal and slick. It’s meretriciously seductive in its surface pleasures. And what makes it so galling: it’s popular. Although I use photorealist methods, I have been known to respond this way to some of the hyperrealism I see—opulently lavish with color and light and detail and yet seemingly devoid of subtle emotional tones. It’s so extreme in its technical skill that mostly it gives you an envious thrill similar to what you might experience while gazing at a Lamborghini on a showroom floor. I’d love to know how that car and those paintings are made, but I wouldn’t feel right bringing either of them home. I think that’s how many fellow painters react to this genre as a whole. It’s cool perfection seems as off-putting as a luxury item.

On the other hand, I could rattle off a list of photorealists whose work I love, as well as work that has the same deadpan, literal accuracy but relies to a lesser degree on photographic technology. (The Dresden painters, the French classicists, for example.) With his lenses and maybe mirrors, Vermeer would be the most beloved practitioner, of course, but many different contemporary painters working in this mode evoke far more than just a lust for looking. Their paintings find ways to convey almost exactly how things look, without any creative meddling, and yet also manage to be individually expressive by employing subtle, personal stylistic jigs—the self-limiting guides of an individual painter’s personal conventions and preferences. Some of these painters evoke a world of memory and stillness and poetry: the sense of order that saturates a certain kind of autumn afternoon, the smell and sound of a golf course, a childhood home in the dusk, or the look of a certain season in the way its light falls on things arrayed under a window. Behind all of that, throughout almost all examples of the genre itself, there’s an affirmation of the Apollonian order embedded in science and technology–its almost ontological presence in modern experience so omnipresent it becomes invisible, though it is what makes possible suburban homes and golf courses and lunches at a favorite diner and lavishly abundant supermarkets and quiet October afternoons scented with burning leaves when you can sit and do nothing in your backyard but listen to a remote motorcycle start up again at a green light. By and large, photorealism shows you how contemporary happiness looks and feels–you look at one of these paintings and realize how happy you actually are. Which is, by and large, what Vermeer wanted to depict as well.

I’m finding myself this year, in my own painting, concentrating on one sort of photorealist work that ought to have its own name: photorealist abstraction or abstract representation would describe it pretty well, though it Continue reading ‘Happiness, courtesy James Neil Hollingsworth’

March 21st, 2019 by dave dorsey

Again while running, two songs came up in my playlist rotation, and the lyrics struck me as a good description of two sorts of people, with two different visions of the world. But maybe not. It seems I fit into both of these groups. Why do both of these songs feel true at the same time . . .

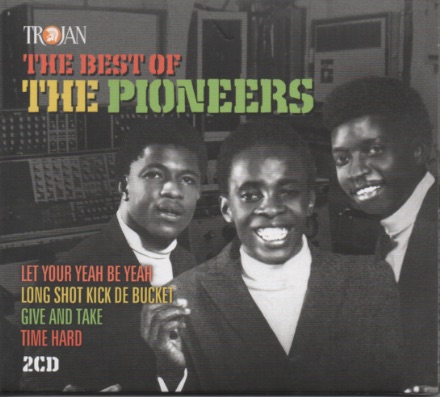

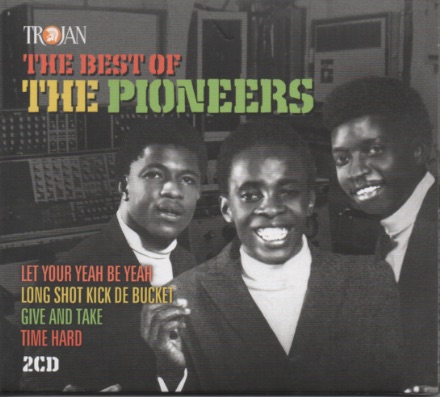

Time Hard, The Pioneers:

Everyday things are getting worse

Everyday things are getting worse

Everyday things are getting worse . . .

I took him down to the market place

And them laugh at my dog

You never see smoke without fire

I said

Oh,

You gotta hold your head up high

Everyday things are getting worse

Everyday things are getting worse

Time so hard, why oh why oh lord

Getting Better, The Beatles

I’ve got to admit it’s getting better (Better)

A little better all the time (It can’t get no worse)

I have to admit it’s getting better (Better)

It’s getting better

Since you’ve been mine

Getting so much better all the time!

It’s getting better all the time

Better, better, better

It’s getting better all the time

Better, better, better

March 18th, 2019 by dave dorsey

Girl with the Red Hat, detail, Vermeer, National Gallery of Art

While I was running today, it occurred to me there ought to be a contrarian challenge directed at idealistic and/or gullible art students before they get launched into the world. Someone should dare them to leave behind, at their death, fewer paintings—or works of any sort—than Vermeer or Piero did. Of course this isn’t difficult. Anyone could leave behind three dozen paintings. Three dozen supremely painted ones, though, is still a challenge. Vermeer’s A-game isn’t in evidence in every one of his 36 extant works. There are around twice that number from Piero della Francesca. The seed to be planted here is that you would spend so much time on each of them that you have a far better chance of achieving something near that rarefied level of quality, without going full-throttle OCD. Finish fewer than most, not more, but make each one count in a way few artists can. It would run counter to most of what the commercial art world herds people toward: don’t get on a track where you’re working for another solo show every three years, don’t try to come out of art school and sell through a metropolitan gallery for significant sums, quit worrying about building a CV with awards and honors, and so on. The whole point would be to ignore the entire system that turns an artist into a one-person factory and simply focus on producing a small number of supremely realized works of art, on your own terms. This is all slightly self-justifying though I have no intention of reducing my slow output even more. Yet I’m thinking about this because my own production has slowed down in the interest of getting things right and focusing on a single series of larger paintings. But the Vermeer Way would be more extreme. For someone thinking on those terms, it would require a day job, or some other humbler and/or more nefarious way to make enough money to get by, short of becoming a professional gambler or day trader—and it would probably mean not having children, though a marriage or other domestic partnership could certainly help, on the economic end. It pays to be gay in the art world, in many ways, but the greater chance it gives you of being childless is a major logistical advantage. Mostly though it would be a way of focusing, while in the studio, on nothing but the quality of the work itself, leaving aside all motivations related to quantity. Imagine posting one image every three or four years on Instagram. You would have six followers, but it would be an event. At the very least, you and a few others would know what you’d done, though you might feel like Crash Davis breaking his minor-league baseball record in Bull Durham with only Susan Sarandon paying enough attention to realize he was a record breaker. Worse fates could be imagined.

March 15th, 2019 by dave dorsey

A couple weeks ago, I was pleased to deliver two still lifes to the Arnot Art Museum for the 76th Regional Exhibition. The show will run from March 16 through June 14. My two contributions are Breakfast with Golden Raspberries and Begonias and Dahlias.

A couple weeks ago, I was pleased to deliver two still lifes to the Arnot Art Museum for the 76th Regional Exhibition. The show will run from March 16 through June 14. My two contributions are Breakfast with Golden Raspberries and Begonias and Dahlias.

March 12th, 2019 by dave dorsey

He was experiencing one of man’s keenest but least understood drives–information compulsion. –Tom Wolfe, Bonfire of the Vanities

I devote myself to painting, and then writing about painting, and I deposit any checks that come my way when someone buys one of my paintings, but I’ve never strategized any of it as a career. I do have a career, but it isn’t the point, that’s all. It seems like a way of warping the whole activity into something it isn’t. A CV resembles a parasitical, invasive life form, imported from the world of business, the way sparrows were brought to North America from Europe. I’m a professional artist, but that term seems almost an oxymoron, and I don’t really think of myself as professional (except for my diligence at the easel) any more than Socrates would have thought of himself as a professional philosopher or Jeremiah Johnson a professional badass. I always think of Van Gogh when I imagine the system in which artists now vie to get onto a career track–prestigious MFA, straight to prominent gallery, applications for grants and residencies, keeping a running tally of awards, all of it as dutiful as the path of a white collar organization man in the Fifties. I keep my CV fresh, I list my awards and summarize my shows and sales. Yet it feels as if I’m applying for a job as a comptroller whenever I submit my CV upon request. Where would Vermeer have found himself in this system? Imagine his exhibition history. After a lifetime of work he’d have had enough for one big solo show at Zwirner, with maybe some other artist to fill out the adjacent space.

My work always takes more time than I would like, but at that constraining pace I know I’m doing good work. The more I become committed to my best possible work, the less new work I have to show, though I’m starting to find ways to shave a little time from the process and actually do more during a day of painting, which is nearly every day of the week.

This puts me into a bind as far as hewing to the ostensible necessity of building a social media following. (In book publishing, this has become brutal. Publishers more and more have no interest in authors who don’t have a following.) As much as I like it—Instagram is the only social media I really use with any regularity, other than this blog which is social only in its availability to anyone. I recognize social media as yet another “professional” taskmaster even though it’s promoted as a service. If you are already known and have a serious following, it can be extremely useful, as is Twitter, which I don’t use at all. If I were far more famous, I would enjoy posting almost anything that seemed worth photographing on Instagram just as a way of being open about who I am. But I’m not, and Instagram isn’t going to get me there. The companies that own these platforms want you to think they will get you there. It’s a lie to make social media feel compulsory, in both senses of the word. They want people to feel irresistibly drawn to them but they also want the stream of content to begin to feel like a duty, an obligation, a necessity. Social media uses FOMO, the fear of missing out, to drive most users (sounds like “drug user” doesn’t it?) to work harder and harder to build a following and get likes, but all of social media has an inherent Catch-22. You need to have a following already by other means to even get noticed, which means there’s no way to gain followers unless you already have them. There are always rare exceptions as in the case of emergent YouTube stars, but any kind of time devoted to Instagram is better spent in front of an easel. Continue reading ‘Better belated than too soon’

March 9th, 2019 by dave dorsey

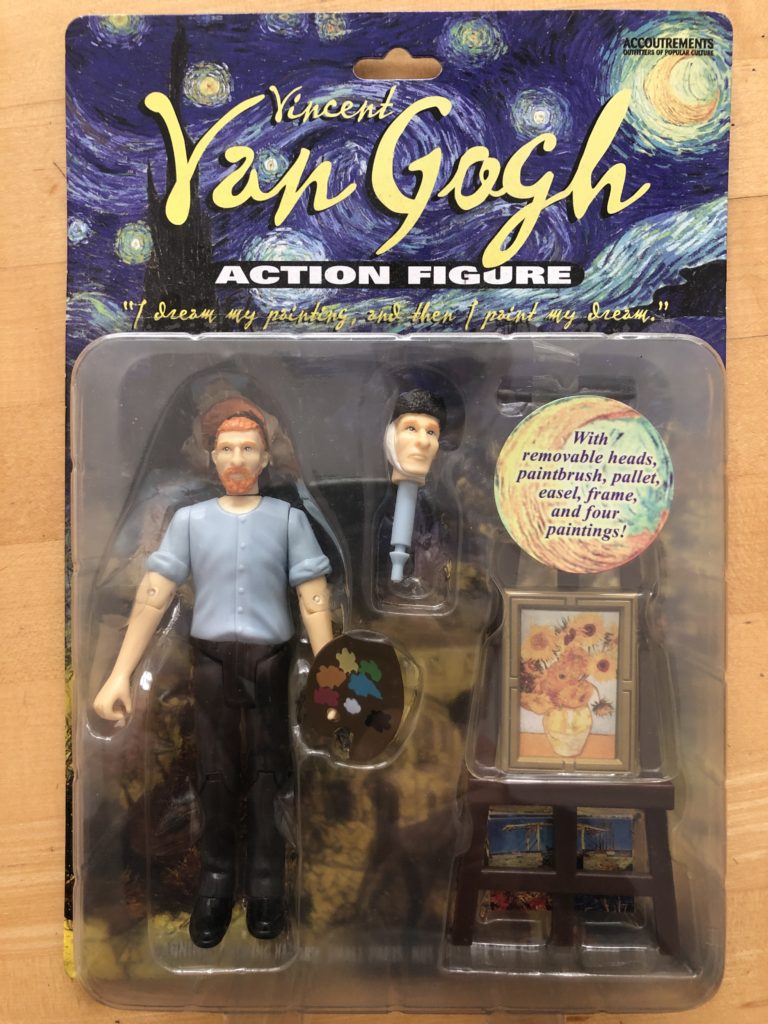

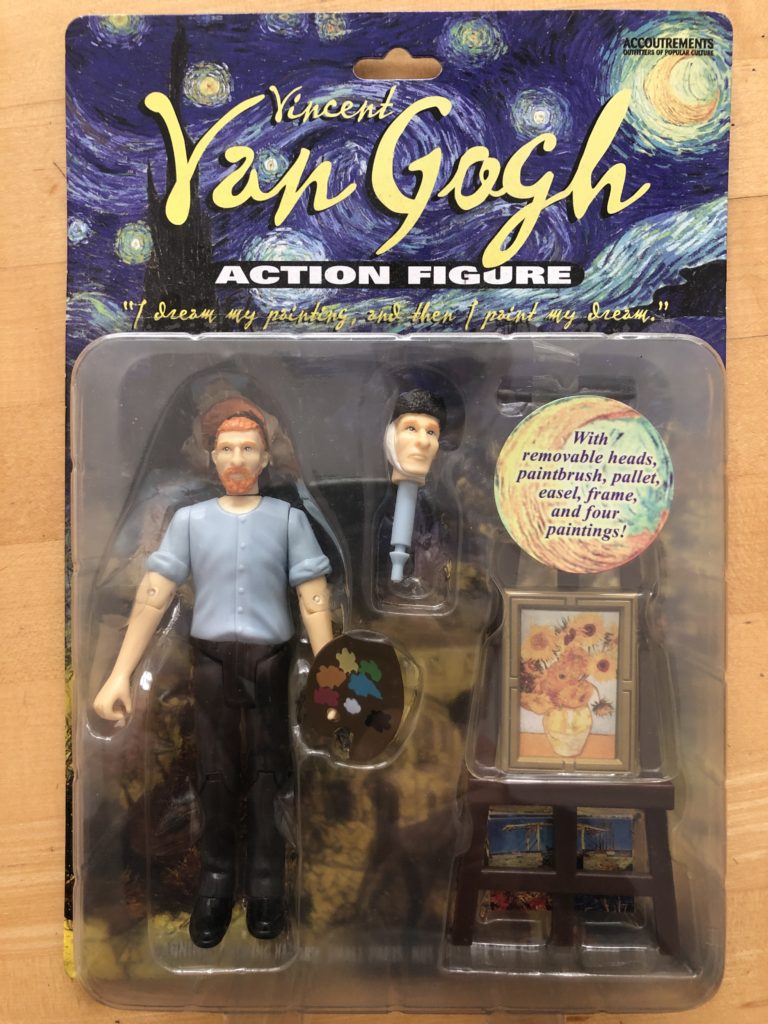

One would think only action painters would be honored as action figures. When you fail to get that Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Genius Award recedes beyond the horizon and MoMA looks less and less likely to put you into its permanent collection, take heart, as always, from Van Gogh’s non-existent career. Even if all else fails, a century from now they might make an action figure of you, only by then it will be fully animatronic and equipped with AI to keep painting in your style, perhaps even better than you do now. At last, action figures will live up to their toy category.

One would think only action painters would be honored as action figures. When you fail to get that Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Genius Award recedes beyond the horizon and MoMA looks less and less likely to put you into its permanent collection, take heart, as always, from Van Gogh’s non-existent career. Even if all else fails, a century from now they might make an action figure of you, only by then it will be fully animatronic and equipped with AI to keep painting in your style, perhaps even better than you do now. At last, action figures will live up to their toy category.

From the back of the package. Wait for it:

Full Name: Vincent Willem van Gogh

Occupation: Painter

Weapon of Choice: Straight Razor

I like how he comes with two heads, the one before and the one after he used that razor to turn his ear into a Valentine.

March 6th, 2019 by dave dorsey

I had a recent email conversation with Chris Pulleyn, an old friend, a former employer, and a central figure at the Rochester Zen Center, where I’ve been a member mostly in absentia for a couple decades. She asked me a few questions about the relationship between my still nascent meditation practice and my painting–so that she could publish some of my work and our conversation in the Center’s publication, Zen Bow. It was a wonderful gesture on the part of the people at the Center, and much appreciated. One thing that was fun about the conversation was that she had a hard time seeing common ground between the few paintings of skulls I’ve done—which struck her as very Buddhist, being emblems of mortality and impermanence—alongside my candy jars. It forced me to think about how much meditation has governed not only the energy I bring to painting, but also influenced my understanding about how painting works. What follows is a condensation of the Q/A in Zen Bow.

I had a recent email conversation with Chris Pulleyn, an old friend, a former employer, and a central figure at the Rochester Zen Center, where I’ve been a member mostly in absentia for a couple decades. She asked me a few questions about the relationship between my still nascent meditation practice and my painting–so that she could publish some of my work and our conversation in the Center’s publication, Zen Bow. It was a wonderful gesture on the part of the people at the Center, and much appreciated. One thing that was fun about the conversation was that she had a hard time seeing common ground between the few paintings of skulls I’ve done—which struck her as very Buddhist, being emblems of mortality and impermanence—alongside my candy jars. It forced me to think about how much meditation has governed not only the energy I bring to painting, but also influenced my understanding about how painting works. What follows is a condensation of the Q/A in Zen Bow.

My first encounter with Zen was in college, when I was a student at the University of Rochester. With a friend from my dorm, I attended my first workshop, run by Philip Kapleau, the center’s founder, in the early 70s. I began sitting then, and have been doing it off and on ever since—constantly trying to establish a daily habit. After I joined as an actual member in the 90s, I spent some regular time in the morning at the center but I’ve drifted into simply sitting at home. It was more than taking up something like yoga. It was, for lack of a better word, a philosophical pursuit.

My first encounter with Zen was in college, when I was a student at the University of Rochester. With a friend from my dorm, I attended my first workshop, run by Philip Kapleau, the center’s founder, in the early 70s. I began sitting then, and have been doing it off and on ever since—constantly trying to establish a daily habit. After I joined as an actual member in the 90s, I spent some regular time in the morning at the center but I’ve drifted into simply sitting at home. It was more than taking up something like yoga. It was, for lack of a better word, a philosophical pursuit.

I came out of high school with a kind of corrosive sense of doubt: a tenacious questioning about the possibility of meaning that seemed urgent but unanswerable. The nature of this doubt is hard to describe without muddling it up, but it was difficult and life-changing and psychologically “totalizing,” to use a word I hear in other contexts now. After contending with this state of unrest for a couple years, as a freshman at UR, I finally got around to reading J.D. Salinger’s Glass family stories, which introduced me to a variety of spiritual traditions: Vedanta, Zen, Russian Orthodox Christianity. His fiction offered me an intersection of references to a variety of spiritual paths. I was so impressed by Salinger, in addition to my curriculum in English lit, I made out a reading list of Salinger’s favorite authors and read them, one after another, as if he had introduced me personally to each of the writers themselves and said, “you two should get to know each other.” Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Proust, Henry James, Keats, Coleridge, and so on, (some of whom I’ve been going back to reread now after all this time.) As a result, I spent the summer after my freshman year at UR reading all of Proust and most of Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard was crucial—my parents were Presbyterian for a while in my teens, and I still consider myself a Christian who uses Tolstoy and Kierkegaard both as an excuse not to go to join a church, but a few of Kierkegaard insights were very close to the paradoxes one faces in Zen practice when trying to break through how the mind entraps itself without realizing it. (I think the conscious, egocentric mind is itself often a sort of self-sustaining trap.) In addition, I made a list of references to spiritual disciplines and other writers mentioned in Franny and Zooey: Ramakrishnma, Mei MORE

March 2nd, 2019 by dave dorsey

Monopoly Board Tokens, oil on linen, 40′ x 40″

I was pleased to learn recently that Monopoly Board Tokens was selected for inclusion in Manifest Gallery’s 9th International Painting Annual. They received 1313 entries from 399 artists and picked 122 works by 73 artists from nearly half a dozen different countries. I was included in the INPA 8 as well, which is available, and will be shipped soon for anyone who ordered it. Thanks, Manifest. Note: this is one of three paintings in a triptych: as part of the triptych it’s entitled Renunciation: Monopoly Board Tokens.

A couple weeks ago, I was pleased to deliver two still lifes to the Arnot Art Museum for the 76th Regional Exhibition. The show will run from March 16 through June 14. My two contributions are

A couple weeks ago, I was pleased to deliver two still lifes to the Arnot Art Museum for the 76th Regional Exhibition. The show will run from March 16 through June 14. My two contributions are

One would think only action painters would be honored as action figures. When you fail to get that Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Genius Award recedes beyond the horizon and MoMA looks less and less likely to put you into its permanent collection, take heart, as always, from Van Gogh’s non-existent career. Even if all else fails, a century from now they might make an action figure of you, only by then it will be fully animatronic and equipped with AI to keep painting in your style, perhaps even better than you do now. At last, action figures will live up to their toy category.

One would think only action painters would be honored as action figures. When you fail to get that Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Genius Award recedes beyond the horizon and MoMA looks less and less likely to put you into its permanent collection, take heart, as always, from Van Gogh’s non-existent career. Even if all else fails, a century from now they might make an action figure of you, only by then it will be fully animatronic and equipped with AI to keep painting in your style, perhaps even better than you do now. At last, action figures will live up to their toy category. I had a recent email conversation with Chris Pulleyn, an old friend, a former employer, and a central figure at the Rochester Zen Center, where I’ve been a member mostly in absentia for a couple decades. She asked me a few questions about the relationship between my still nascent meditation practice and my painting–so that she could publish some of my work and our conversation in the Center’s publication, Zen Bow. It was a wonderful gesture on the part of the people at the Center, and much appreciated. One thing that was fun about the conversation was that she had a hard time seeing common ground between the few paintings of skulls I’ve done—which struck her as very Buddhist, being emblems of mortality and impermanence—alongside my candy jars. It forced me to think about how much meditation has governed not only the energy I bring to painting, but also influenced my understanding about how painting works. What follows is a condensation of the Q/A in Zen Bow.

I had a recent email conversation with Chris Pulleyn, an old friend, a former employer, and a central figure at the Rochester Zen Center, where I’ve been a member mostly in absentia for a couple decades. She asked me a few questions about the relationship between my still nascent meditation practice and my painting–so that she could publish some of my work and our conversation in the Center’s publication, Zen Bow. It was a wonderful gesture on the part of the people at the Center, and much appreciated. One thing that was fun about the conversation was that she had a hard time seeing common ground between the few paintings of skulls I’ve done—which struck her as very Buddhist, being emblems of mortality and impermanence—alongside my candy jars. It forced me to think about how much meditation has governed not only the energy I bring to painting, but also influenced my understanding about how painting works. What follows is a condensation of the Q/A in Zen Bow. My first encounter with Zen was in college, when I was a student at the University of Rochester. With a friend from my dorm, I attended my first workshop, run by Philip Kapleau, the center’s founder, in the early 70s. I began sitting then, and have been doing it off and on ever since—constantly trying to establish a daily habit. After I joined as an actual member in the 90s, I spent some regular time in the morning at the center but I’ve drifted into simply sitting at home. It was more than taking up something like yoga. It was, for lack of a better word, a philosophical pursuit.

My first encounter with Zen was in college, when I was a student at the University of Rochester. With a friend from my dorm, I attended my first workshop, run by Philip Kapleau, the center’s founder, in the early 70s. I began sitting then, and have been doing it off and on ever since—constantly trying to establish a daily habit. After I joined as an actual member in the 90s, I spent some regular time in the morning at the center but I’ve drifted into simply sitting at home. It was more than taking up something like yoga. It was, for lack of a better word, a philosophical pursuit.