December 19th, 2019 by dave dorsey

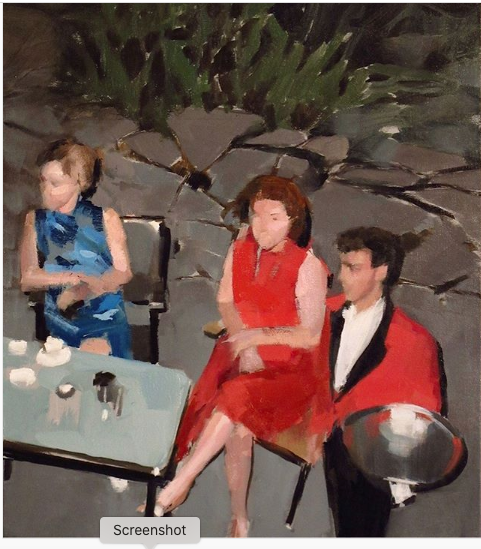

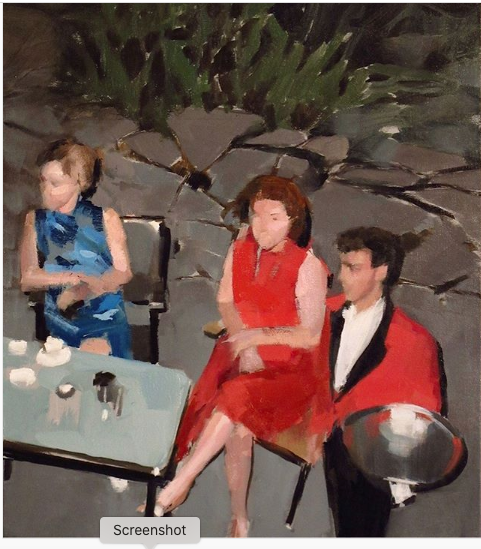

Mark Tennant, 20 x 16

Mark Tennant, 20 x 16. That’s all I know about this painting by an artist who has turned a bit of a corner in the past year or two–the simplicity of his execution has become extraordinary given how convincingly he puts one perfect tone alongside another. These chunks of color do exactly the job he asks them to do. In some cases he creates an almost expressionist surface that resolves, after a bit of viewing, into a bracingly convincing glimpse of women caught in a candid moment not intended for public consumption. No title, no medium nor indication of the support, though it’s almost certainly oil. He posts his work on Instagram and at his website, but it’s all untitled as far as I can tell. I did a post about an earlier painting of his not long ago, but couldn’t resist posting again, it’s so impressive. I found his scenes off-putting at first, murky and seemingly jaundiced visions of people lost in an eroticized world of youth and folly. Now I’m not bothered by lost-in-the-dark quality of his figures. The brushwork is so deft and accurate and minimal, as if he were the Fairfield Porter of cultural decline. At first, his work briefly brought to mind Eric Fischl and Richard Prince’s ironically prurient stuff, but this latest work feels more like early Richter. There’s a muted compassion in all of it, even though the scenes are illuminated unsparingly and the figures are mostly faceless. It all looks as if he has discovered troves of snapshots, Polaroids maybe and worked from them quickly–the way Martin Mull buys boxes of old, unwanted family shots at garage sales to use as sources. The bruised sexiness that runs throughout Tennant’s work is suppressed and seems almost accidental in many of the images–the young women are mostly unaware that there’s a guy with a camera eavesdropping on their misdemeanors, but in more than one of the paintings the women are hiding their faces. Many seem lit by flash photography, which adds to the tabloid feel that runs throughout, the awkwardness of bodies caught off balance or hunkered down in self-defense. He gets exactly how a single bright light source plays on objects in dim surroundings and his extremely abbreviated handling of paint captures the look and feel of an onlooker snapping a furtive high-contrast exposure of a compromised subject. The shot above could be from a cocktail party in the Hamptons or Connecticut, some partier with a Kodak Instamatic up on a balcony, gazing down at his bored fellow celebrants, the butler or caterer passing with his gleaming tray, with nothing to offer the idle women on the flagstone patio. The elegance and evening formality seem imported from America’s economic heyday, or else from last week in certain increasingly wealthy and isolated zip codes. Either way these privileged figures look as exposed and spiritually endangered as nearly everyone else Tennant captures unaware.

December 16th, 2019 by dave dorsey

Flowers in Starlight, enamel on canvas, 24×24, 2018

The artist’s individual struggle, individuation as Jung would have put it, as it worked itself out in her own career:

I wanted to paint what today looked like or felt like. But as I just grew older it didn’t seem as important to make paintings that were necessarily as contemporary as possible. I wanted to make paintings that I wanted to make. You don’t have a choice. You can try to make the work you think everybody likes, but that isn’t going to work. If I had never changed then possibly I would just be that person who made paintings that looked as if they were done in the 90s.

–Inka Essenhigh

I didn’t want to be light and girly and trivial and I suddenly was and I loved it and it was all okay. And I had an immediate sense of relief. I could tell stories and I knew that I was on the right track for making something that was important to me. I could pursue what you might call “the inner world.” I could sit down and look for certain images I wanted to paint and they would look a certain way, they would feel a certain way. They could have that feeling of child-like wonder and I could bring it forward.

–Inka Essenhigh

December 7th, 2019 by dave dorsey

I’m beginning to realize it’s entirely fair to classify some of my work as Pop, and I’m comfortable with the idea. It doesn’t clarify anything—categorizations and schools and movements just obscure what’s actually going on in a painting—but I’ve begun to warm up to what Pop was doing, historically. It made me uncomfortable in the past, because I didn’t arrive at what I do as a way of emulating Pop Art at all. I’m sympathetic with the non-intellectual aims of that movement, the notion that visual art can be accessible and enjoyable to anyone with eyes and that visual art can, maybe should be, entirely a perceptual matter. I’m happy that Arthur Danto considers Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes to have been a major philosophical meditation calling into question the nature of art and putting an end to the notion of progress in the history of painting—but I don’t think that sort of philosophical investigation was Warhol’s mission. Whether it was or wasn’t, Danto’s insight made me realize, in my thirties, that I could consider myself a contemporary visual artist, rather than just a latecomer. I don’t think Danto would agree with me that people now have permission to do exactly the sort of thing done in the past, without irony, and create work that is absolutely vital and compelling and fresh. But his insights make this conclusion inescapable.

I conclude from Danto’s thesis that for the past seventy years or so artists have been free to do anything at all, including exactly the sort of work that has been done in the past, and what they produce can be considered entirely relevant and contemporary. Everything is permissible because anything can be art. (This doesn’t mean anything is great or even good art: that’s as rare as it ever was.) Ending the tyranny of art history is the last, great liberation for individual painters—and it was Danto’s genius to recognize all of this. The challenge now is to become oneself, in whatever idiosyncratic way works, even if the outcome looks like a painting rooted in traditions from thousands of years ago. Picasso already understood this between the wars when he was borrowing stylistic inspiration from Ingres and the figures on attic vases for the Vollard Suite. Continue reading ‘Fine, Call Me Pop’