Archive for January, 2020

January 30th, 2020 by dave dorsey

View of Norra Djurgardsstaden reurbanization project around Gasklockan 1 and 2, oil on linen, 33″ x 77″

On my brief visit to New York City, to spend a few hours at the New York Public Library’s J.D. Salinger exhibit a few days before its final weekend, I caught the new installation of work from three artists at George Billis Gallery. It was the only exhibit of new painting I was able to see, because I timed my visit on the worst possible day—between exhibitions at almost all the galleries in Chelsea. Billis had a leg up on all the others and was already prepared for the following night’s opening.

I was the only visitor at the time, with Billis himself clicking away on the computer in back, and Todd Gordon—the painter whose work had been hung in the main gallery space—standing at the window on a call with his wife who was arriving at the airport, having flown in from Sweden with the kids. I didn’t realize he was the exhibiting artist until I’d toured the entire gallery and wandered back to ask him, in my own charming way, where to find a rest room. I’m relieved to report that I never got to my question, because he introduced himself, and we launched into a discussion of the state of the art world at the moment—a delightful series of agreements about almost everything. He was intense, making his points without belaboring them, as I was more likely to do, but amiable and generous in his eagerness to endorse some other contemporary painters whose work would be on view at galleries he directed me to visit.

He’s tall, fit, with the bearing and aura of a guitarist who would prefer to be considered alternative, a good sense of humor, quick to pick up on the slightest irony and add his terse two cents. He had the quality of attention, the alert bearing, of someone who is out in the field, engaged in the hunt, a fellow soldier, not just someone making observations about the battle from a safe distance. I had the sense that, he was doing what we’re all doing: trying to puzzle out, not just from year to year, but from minute to minute, whether or not genuine art can rise up and float over the slippery, unreliable ocean of wealth that grants painters an income and makes a few rich, for better or worse. It’s an experiment with as many possible outcomes—and few, if any, are repeatable—as there are painters.

His painterly landscapes and cityscapes, many similar to urban scenes that he has been doing for quite a while, were compellingly intricate and fresh. In addition, he’d included some more traditionally rustic wooded settings, all of them just as unsentimental and exacting as the city scenes. He works from direct observation, and though he describes himself as a Brooklyn artist on his website, he resides in Sweden and paints both there and in Italy. Aside from his considerable skills at capturing tone and value and conveying the volume of what he’s depicting, what I liked most was the panoramic aspect ratio, as it were, of the work—extremely wide and shallow, like a sideways scroll. It gave me the sense of the proliferation of the world, the seemingly superfluous expanse of natural life and fabricated objects. It’s a meditation on the plenitude of every big and little thing out there—mundane, wonderfully ordinary, and suited to whatever it happens to be doing, or not doing, wherever it stands in the scene.

“This is great work,” I said.

“I’ve got more. I’ve got enough to fill the other two rooms,” he said, smiling ruefully, motioning toward the other smaller solo shows with a slight air of frustration.

It was a nice space, on an upper floor with plenty of natural light, and though I liked the way Billis was able to organize three solo shows simultaneously, I could sympathize with Gordon’s eagerness to get as much exposure as possible, if he had so much other new work not on view. We were actually occupying temporary quarters, next door to George Billis’s permanent gallery, which was undergoing a reconstruction. This space was on loan to him for the current shows.

I asked Gordon what it was like to live in Sweden.

MORE

January 27th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Jeremy Duncan, Ford Pickup, gouache on paper. Instagram

January 24th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Marie Therese Walter and Maya

The desires of the heart are as crooked as corkscrews.

—-W.H. Auden

1

When I was visiting the L.A. County Museum of Art a year ago, I came across the final print from Picasso’s Vollard Suite in Fantasies and Fairy Tales, a small, beautifully curated selection of graphic work by various artists from around the early 20th century. It immediately changed my emotional response to Picasso as a visual artist. It struck me as fine in a way so much of his work isn’t—there was a subservient care for the image itself that seems largely absent from so much of Picasso’s work. Usually, he forces his images to work, creating an image that feels kinetic and improvisational, without many pains taken for any other quality. I’d seen reproductions of the print, but never before actually noticed the self-effacing craftsmanship that went into the dreamy light that illuminates his figures in the Vollard print. By establishing that diffuse stage lighting, from below the players, with the light source hidden off to the left at ground level, he bathes the  last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order Picasso Prints: The Vollard Suite, and to keep returning to it through the rest of 2019, off and on studying what Picasso had done in it, leading me to conclude that these prints may have been his most original and personal (those two adjectives are mutually dependent) contribution to Western art. Much of the suite may not rank as his finest work on technical grounds, nor his most beautiful, nor his best on many different levels, but they are what I would save of everything he did, if I had to pick one achievement of his to take to a desert isle. I suspect no one else in the history of art has done what Picasso did here: it’s almost as if he is undercutting and cancelling everything he’s accomplishing as he achieves it, fusing the act of creation and destruction and creating images of great beauty in the process. All of this was in the service of the brief stirrings of a moral self-doubt he managed to suppress in himself once he’d painted Guernica, which served as a sort of footnote to this series of prints.

last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order Picasso Prints: The Vollard Suite, and to keep returning to it through the rest of 2019, off and on studying what Picasso had done in it, leading me to conclude that these prints may have been his most original and personal (those two adjectives are mutually dependent) contribution to Western art. Much of the suite may not rank as his finest work on technical grounds, nor his most beautiful, nor his best on many different levels, but they are what I would save of everything he did, if I had to pick one achievement of his to take to a desert isle. I suspect no one else in the history of art has done what Picasso did here: it’s almost as if he is undercutting and cancelling everything he’s accomplishing as he achieves it, fusing the act of creation and destruction and creating images of great beauty in the process. All of this was in the service of the brief stirrings of a moral self-doubt he managed to suppress in himself once he’d painted Guernica, which served as a sort of footnote to this series of prints.

2

The Vollard Suite isn’t what I like most from Picasso, which have to be his portraits of various lovers, wives and children, and the often beautifully lit paintings of massive, neoclassical women. Some of his abstracted figures are powerful, but most of his work as he was inventing Cubism with Braque seems monotonous in retrospect. What makes the Vollard Suite unique is also what makes it ahistorical, though the series is clearly of its time: modern in the sense of being thoroughly anchored in surrealism, with a glance or two back toward Cubism. It’s also postmodern in its many self-referential subversions of its own beauty. Yet it’s mostly neoclassical in spirit, tone and ambition—to an almost reactionary degree—though his masterful lines morph into something rich and strange before he’s finished. These prints hint at a yearning for innocence through the intensity of their plea for lucidity, for an impossible way out of the blind passions that invest them with life. They yearn for goodness and wisdom, and even offer the glimpse of an ambiguous spiritual harbor, which remains just out of reach. MORE

January 19th, 2020 by dave dorsey

A sample of Leo Ragno’s portraiture, from Instagram

January 16th, 2020 by dave dorsey

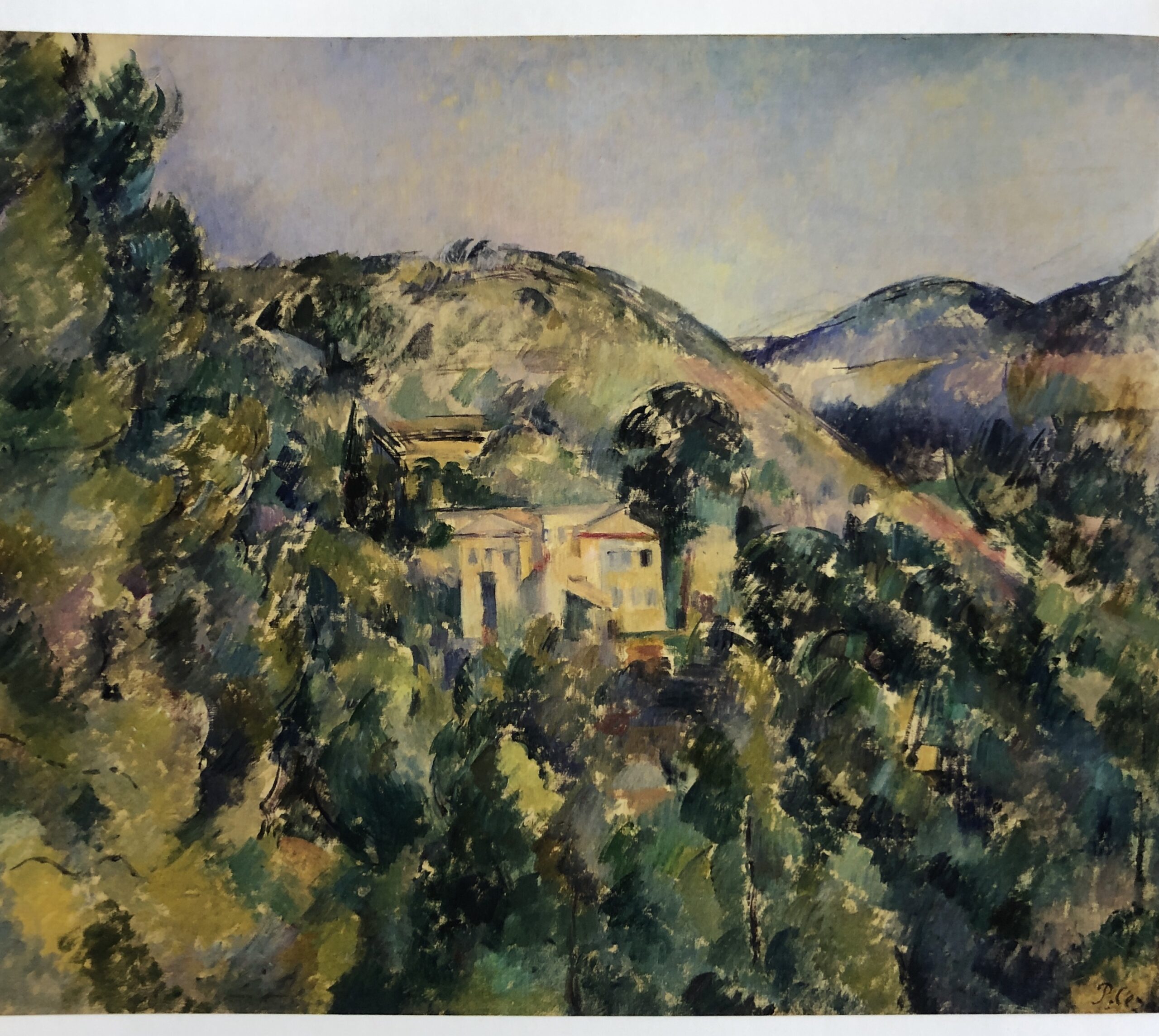

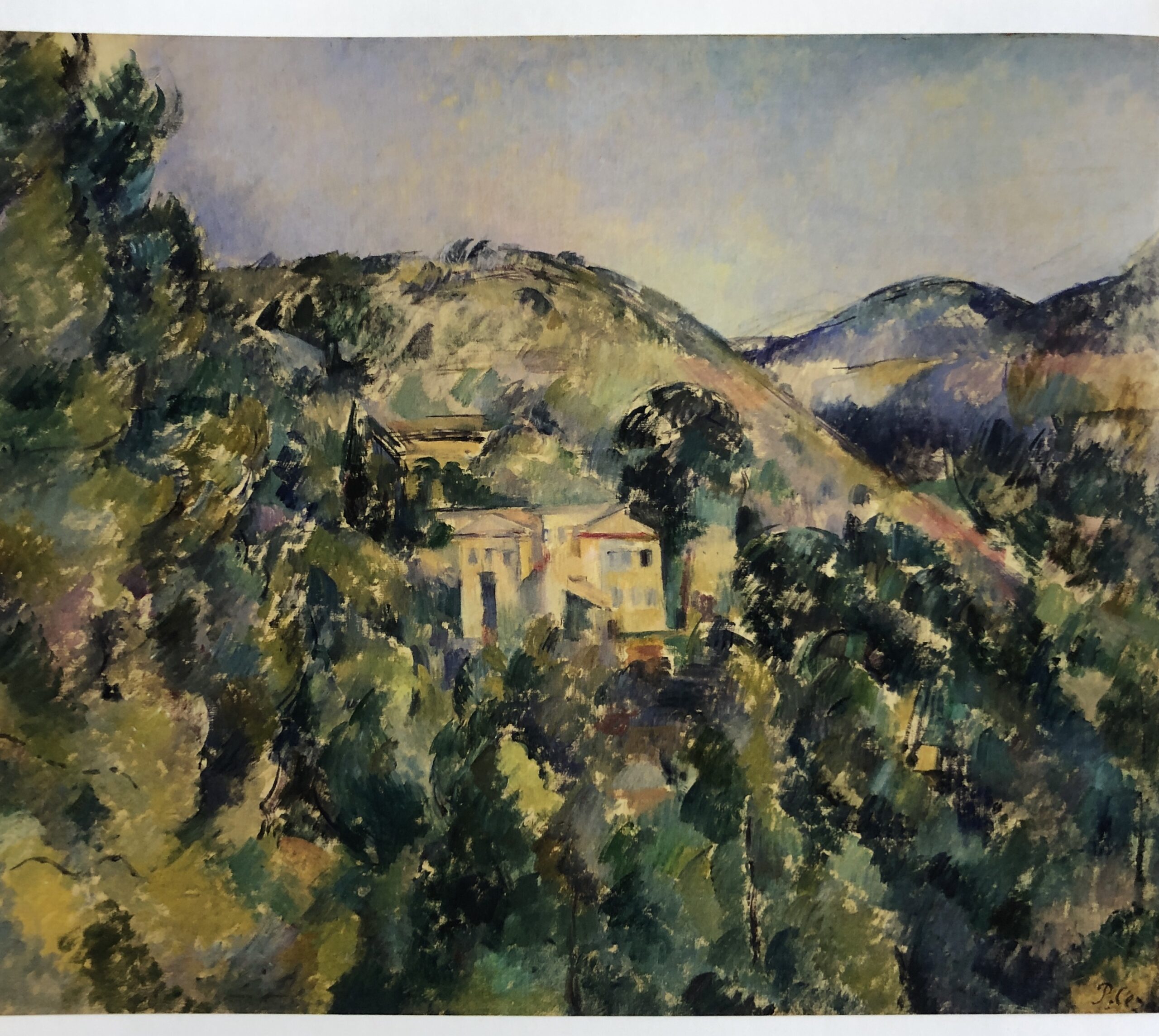

View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph, Metropolitan Museum of Art

I saw this painting almost exactly ten years ago at Cezanne and American Modernism at the Montclair Art Museum. After all these intervening years, I finally bought the catalog for the show. It’s a hardbound book once in the collection of the Art Institute of Pittsburgh Library, with the little envelope for the library loan card still glued just inside the cover. Purchased through a third party on Amazon, the book was finally a bargain. I bought it because seeing this show revealed so much about Cezanne’s influence on American painters and because this particular painting had such an impact on me when I was at the museum. I wanted to see the work in the show again after all this time.

The almost iridescent quality of the variations in color from the hillsides down into the forest, the way in which each mark hummed vibrantly in harmony with every other mark in that field of paint, left me more in awe of Cezanne’s color than ever before. I’m struck more and more by how Cezanne’s greatness has, for me, so little to do with his enormous historical influence. It’s ironic to react that way to a show designed to confirm his enormous affect on later American painters. But it seems that his influence had less do with with his theories–in other words his position in history–and seems so much more a result of the unique, lyrical feeling his paint inspires. His color, his handling of oil is almost always understated, and he seems to always find combinations of tone that make time itself visible–as Vermeer does in a different way. It derives from the intensity of his subdued passion for what he sees as he translates it into paint, which is hard to square, so to speak, with his famous dictum about interpreting nature geometrically, the advice that gave birth to Cubism. I wonder if his stress on seeing nature as sphere, cone and cylinder was merely an arbitrary way of imposing self-restraint to temper his passion for the colors of oil paint. He forced himself to think about form and volume rather than color and as a result his color became more subtle and unique. His actual achievement could have been almost as an incidental byproduct of the geometrical guidelines uppermost in his mind–even though color was what drove him to paint. Somehow, in the lower left hand corner, I see Gorky, of all people and I don’t mean the early paintings Gorky did which are hugely talented imitations of Cezanne. I mean his later paintings and his self portrait with his mother–the line and shapes and even a bit of the color. Cezanne is a marvel–and one can see why he could be classified as both an Impressionist and Post-Impressionist, though he was unlike everyone else in any category. He was perfectly himself.

January 13th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Les Indes Galantes, Johannes Muller Franken, at Louis K. Meisel Gallery

I saw this painting some years ago at an invitational group show at OK Harris, not long before the gallery closed, seemingly another little heartbreak in the cancer of real estate inflation in Manhattan driving out all sorts of businesses that operate on a human scale and replacing them with gentrified real estate and Google office space. I wonder how a simple corner bodega survives this slow, torturous cleansing by the tsunami of finance driving our metropolitan economies. That isn’t really why the gallery closed, but I’ve been wanting to rant about out-of-control inflation in big American cities. Many galleries have closed–or moved away like Arcadia, happily thriving in Pasadena now–because they can’t afford to stay open. In reality, its founder, Ivan Karp left instructions for how to wind down the operation when he died in 2012, and the managers of the gallery were simply following his dictates. He picked the name OK Harris because it sounded tough and American, like a riverboat gambler. Visiting on a whim five years ago, I saw one painting after another that startled me with its excellence, and this one left me gobsmacked at the raindrop-by-raindrop realism in mellow counterpoint with the scene’s romance and Maxfield Parrish color. Apparently, it’s still available at Meisel. How is that possible?

January 10th, 2020 by dave dorsey

The Cartographer, mixed media, 39” x 132′ x 104″, 2019

I loved the artist statement (I can’t remember if I have ever those words in the past) for this installation that won Manifest’s coveted $5,000 Manifest One award and single-work exhibition. Here is the email announcement with Indiana artist Damon Mohl’s statement below. I like the sense of exhaustion and lostness in his vision, which seems appropriate as a viewpoint on Western culture. But I loved , his statement about the genesis of his creative work–which apply to the most compelling creative work in general.

Manifest’s projects are carefully crafted exhibitions of engaging works from around the world, judged and chosen by a dynamic jury of working artists, creative professionals, scholars, and educators. Once each year, we honor an exemplary artwork and test the extremes of our selection process in ONE: The Manifest Prize.

The nonprofit Manifest Creative Research Gallery is proud to be celebrating a decade offering this momentous award supporting artists making exceptional art. Now in its 10th year, one artwork has been chosen from a pool of nearly 900 works by 192 artists from 41 states and 12 countries to stand out as the best in one of the largest artist responses this project has ever received. Seventeen jurors from across the U.S. participated in this multi-stage selection process.

It should be noted that the winner and finalists*, 11 works, represent the top scoring 1% of the jury pool. The winner represents the top one-tenth of 1% of the jury pool.

We are proud to award this year’s $5000 Manifest Prize and corresponding ONE exhibit to Damon Mohl for his work, “The Cartographer” which will continue on view in Manifest’s Central Gallery through January 10th.

Of his work the artist states:

“In 2018 I spent a month traveling the north and south islands of New Zealand. Leading up to the trip, I had completed numerous sketches for an experimental film. In truth, the many fragmented images never connected, and when I arrived I started filming without a clear sense of the project. Traveling in a camper van, I gradually woke up earlier each day and heard a cacophony of birds singing before dawn. One song, in particular, stood out because of its melodic, contemplative nature and haunting strangeness. I learned this was the song of the Bellbird, and for the rest of the trip, I set my alarm so I could make audio recordings of the Bellbird’s morning song. These recordings led me to a new idea, and I ended up creating an entirely different film.

I find it compelling the way an image or sound can lodge itself in the subconscious and open up an expansive idea. Creatively speaking, ideas that originate from a presumed understanding or with a specific goal are often prodded and forced into existence. Outcomes are narrow and predictable, even before they are developed. Everything is over before it even begins. The most exciting ideas arrive as mysteries. They create enigmas to be explored but never fully understood. Art is the language that embodies and evokes that which cannot be rationalized or explained with words and it is this revelatory journey that keeps me fascinated and dedicated to the process of creating. My work is firmly rooted in metaphorical narrative, but at the project’s origin, I relinquish as much control as possible. I often reach a place on sustained projects where I can no longer remember what propelled me forward in the first place. If the origin remains intact, it was strong enough to stand the test of time. If it fades, what came after was much more interesting to me.

The Cartographer was recently created for an exhibition of costumes, objects, and set pieces utilized in five different film projects over the past four years. Thematically, the film connected to this piece tells the story of a man whose mind is locked in an endless cycle, in which he repeatedly imagines himself on doomed 19th century expeditions. The voice-over narration provided on the nearby wall is also from the film.“

Artist Biography:

Damon Mohl (b.1974) is a filmmaker and interdisciplinary artist. His work bridges drawing, painting, collage, and sculpture with digital technology to create experimental as well as narrative-based films and works of art. He received his BFA in drawing and painting from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia and his MFA from the University of Colorado, Boulder. With a focus on filmmaking, his graduate thesis film was nominated for a Student Academy Award in the experimental category. He exhibits his work nationally, and internationally his films have screened in over thirty countries. He is currently serving as an assistant professor of art at Wabash College in Indiana.

January 7th, 2020 by dave dorsey

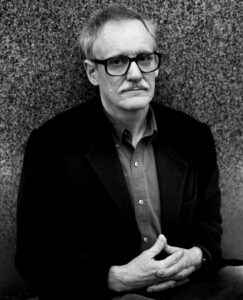

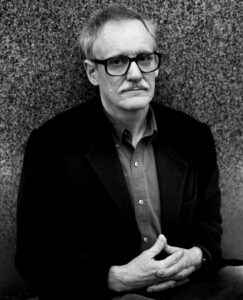

Peter Schjeldahl, courtesy The New Yorker

I was delighted when Jim Mott sent me some excerpts from Peter Schjeldahl’s sayonara at The New Yorker, inaugurating his retirement. I spend so little time reading magazines now; I missed it. May he move on to write a book, if he survives his battle with cancer long enough. The prospects don’t sound good. He’s always been my favorite art critic. I didn’t realize he had a faith, but it sounds as if it didn’t emerge until he quit drinking. Maybe I am reading too much into a couple sentences. In this cultural climate, it’s a brave move, albeit a bit quieter than Kanye’s, to offer a shout out to Christianity, which now seems to be equated unfairly with deplorable politics. It feels as if we are living in the cultural Dark Ages. (It helps if you quote Simone Weil; that “cherry on top” is a nice touch.) His judgments have almost always struck me as unimpeachable and delivered with wry self-awareness, meaning humility. The humility grows here to the proportions I consider de rigueur for an artist, and especially a critic. I agree with nearly any self-skepticism: I don’t know much, and maybe someday, if I’m good, I’ll know nothing, along with Socrates. Danto often has a similar tone of implied disclaimer: Well, this is how it looks to me, I could be wrong, but I don’t think so. But Schjeldahl’s doubt is less philosophical and more personal, hence more engaging and intimate. His first paragraph below says precisely what I recognized a few months ago after my father’s death, when I came across the Google street view photograph of the house my wife and I lived in during the first few years of our son and daughter’s childhood–the photograph did everything a work of art ought to do, and it was simply the tiny artifact of some camera mounted on top of a car moving past the house in the most impersonal way possible. It was essentially a surveillance shot. But it contained more than my world from those years; it gave me a window into the entire world, emotionally, imaginatively, and in some other way I don’t have language to pin down. I had been punished into receptivity at that point, granted, but there you go. That’s how it works. Danto would smile at the fact that the Google street view shot was art for me right then and there–though it would contradict his argument about the need for meaning–but it’s exactly what Schjeldahl is getting at.

From Schjeldahl’s farewell, courtesy Jim’s email:

To limber your sensibility, stalk the aesthetic everywhere: cracks in a sidewalk, people’s ways of walking. The aesthetic isn’t bounded by art, which merely concentrates it for efficient consumption. If you can’t put a mental frame around, and relish, the accidental aspect of a street or a person, or really of anything, you will respond to art only sluggishly.

I like to say that contemporary art consists of all art works, five thousand years or five minutes old, that physically exist in the present. We look at them with contemporary eyes, the only kinds of eyes that there ever are.

I retain, but suspend, my personal taste to deal with the panoply of the art I see. I have a trick for doing justice to an uncongenial work: “What would I like about this if I liked it?” I may come around; I may not. Failing that, I wonder, What must the people who like this be like? Anthropology.

Simone Weil said that the transcendent meaning of Christianity is complete with Jesus’ death, sans the cherry on top that is the Resurrection. I think so.

“I believe in God” is a false statement for me because it is voiced by my ego, which is compulsively skeptical. But the rest of me tends otherwise. Staying on an “as if” basis with “God,” for short, hugely improves my life. I regret my lack of the church and its gift of community. My ego is too fat to squeeze through the door.

Disbelieving is toilsome. It can be a pleasure for adolescent brains with energy to spare, but hanging on to it later saps and rigidifies. After a Lutheran upbringing, I became an atheist at the onset of puberty. That wore off gradually and then, with sobriety, speedily.

January 1st, 2020 by dave dorsey

Envy, from Giotto’s Arena Chapel frescoes

To paint pictures is to live in a state of paradox. What I intend usually just points me in the direction of what I achieve, and by not achieving quite what I want, I sometimes succeed in ways I wouldn’t have imagined and may not even realize. Occasionally I invest paint with something far better than what I could have intended or predicted. In every success, there’s a bit of surprise, if not discovery.

When you begin to realize how great paintings aren’t necessarily limited by whatever outcomes the painter desired, it dawns on you that this is how life itself works, almost invariably. All of your representations, all of your mental pictures of what matters in life fail to embody what it is you think those images represent. Try to picture anything—goodness for example—and whatever instance of goodness you imagine will fail to capture what it actually is. And, even if you lower your sights and accept the consolation prize of depicting what’s actually visible in life, even then, there’s shortfall. What you do picture to yourself as familiarly good will rarely resemble how living, new instances of goodness actually appear.

Early in Swann’s Way, Marcel Proust elaborates on a physical similarity between his cook’s pregnant kitchen-maid and one of Giotto’s figures of virtue and vice in his Paduan frescoes. It’s a little running joke between the novel’s protagonist and Swann, when he comes to visit and asks how things are going with Giotto’s Charity. As his focus shifts from the kitchen-maid to the painter, the way Proust elaborates on the Gothic painter, circling around his subject, reminds me of how Francis Bacon, in his essay on it, seems to turn the subject of Truth inside-out and then outside-in, until you are almost completely disoriented but left with a kind of Socratic doubt about your own callow assumption that you can actually know Truth. In the same way, you think you’ve understood Proust’s point and suddenly he seems to be saying just the opposite—this symbolizes X, but X is nowhere visible in the behavior depicted and yet the reality of X is embodied by it. Come again? It does make sense, but at first it feels like riding in circles on a Mobius strip. All the while he asks you to keep reconsidering what exactly is happening in Giotto’s paintings of virtue and vice—forcing you to go back and look at them. Which is both the first and last step in letting a painting do its work.

For years, I’ve considered Proust a purposely amoral novelist, someone so driven to see exactly what’s happening in human behavior and human consciousness, that he can’t stop to pass judgement on the behavior he depicts—not letting discriminations of good and evil constrain his phenomenology. Passing judgment on something gives you an excuse to ignore what you’re seeing. I’m beginning to think differently. In my third reading of this novel right now (first in college, second when the Kilmartin translation was published), I’ve delved only a hundred pages into the book, and it seems he was constantly thinking of goodness, interested in why his many of his characters found it so difficult to see and embody it. His ability to convey goodness was so fresh, so unsentimental, that it’s hard to realize what he’s doing as it happens on the page—in a way analogous to his consistent depiction of social and sexual relationships as detours that usually lead away from an authentic life. In a way similar to how I’m seeing this new dimension in Proust, this year I’ve become more and more interested in visual art that seems to be doing exactly the opposite of what I think painting and drawing should do when operating in its most innate way. Painting that has always struck me as the most fully realized has no meaning. Any effort to extract meaning from it is, in a way, to look away from what’s actually happening in the work, the awareness it can generate, and nullify it by translating it into thought. (In the same way, the best passages of Bergotte’s writing have an impact on Proust’s narrator unrelated to their significance. In one of his book’s quietly amusing moments, Bloch advises him to read only poetry that means nothing.) What’s most powerful in a work of visual art has nothing to do with meaning: deconstructing it will get you places, but it won’t replace the looking and often gets in the way. MORE

last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order

last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order