March 15th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Jasper Beckx’s portrait of Don Miguel de Castro, a Congolese ambassador to the Netherlands, from 1643.Credit…Statens Museum for Kunst

From Black in Rembrandt’s Time, at the Rembrandt Museum in Amsterdam (closed at the moment in the European shutdown.) From the museum’s website: “For years I’ve been looking for portraits of black people like me. Surely there had to be more than the stereotypical images of servants, enslaved people or caricatures? I found the alternative in Rembrandt’s time: a gallery of portraits of black people who are depicted with respect and dignity.” – Stephanie Archangel, Guest Curator

March 13th, 2020 by dave dorsey

The Song of the Lark, Jules Adolphe Breton, Art Institute of Chicago

Bill Murray tells the story of how he stumbled onto this painting and how it saved his life, more or less, at an especially discouraging moment in his early career. Or at least it showed him how he had nothing to be discouraged about. I love how Breton manages to illuminate the figure with the cool, blue light of the dawn in the west rather than the direct and warm light of the sunrise in the east. It somehow conveys the clemency of the young woman’s experience hearing the bird to inaugurate a day of work. And, who knows, maybe we need to say a few words of gratitude to this painting for Ghostbusters, Lost in Translation, and Rushmore, not to mention a couple of the best moments in Tootsie.

March 10th, 2020 by dave dorsey

JERRY: I have to go meet Nina. Want to come up to her loft, check out her paintings?

GEORGE: I don’t get art.

JERRY: There’s nothing to get.

GEORGE: Well, it always has to be explained to me, and then I have to have

someone explain the explanation.

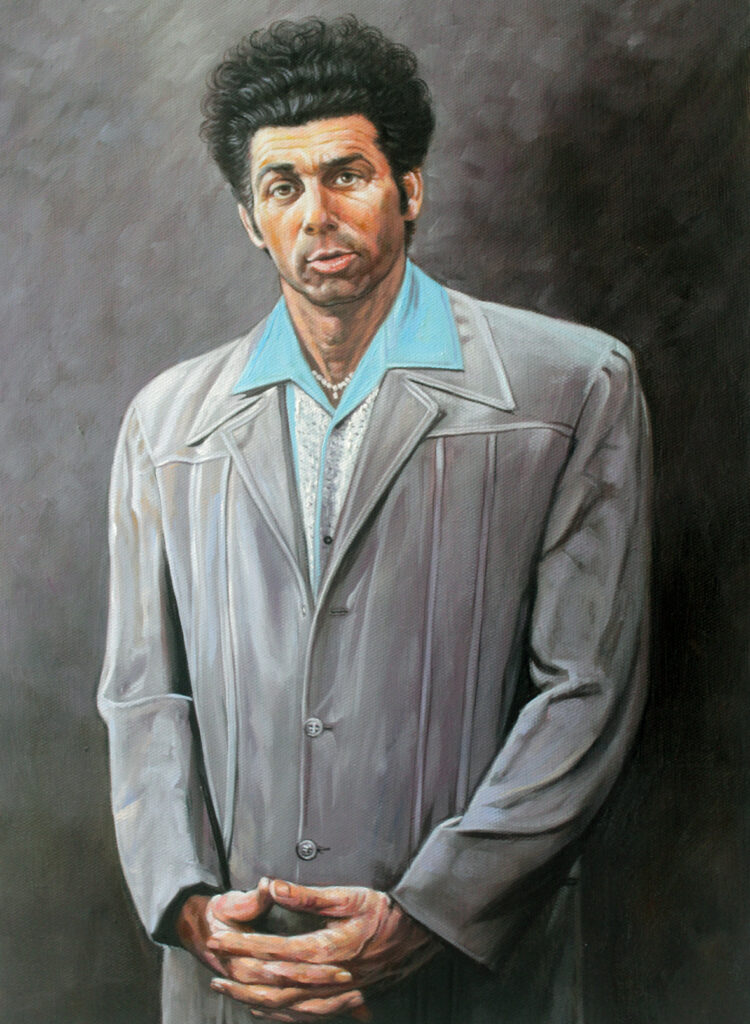

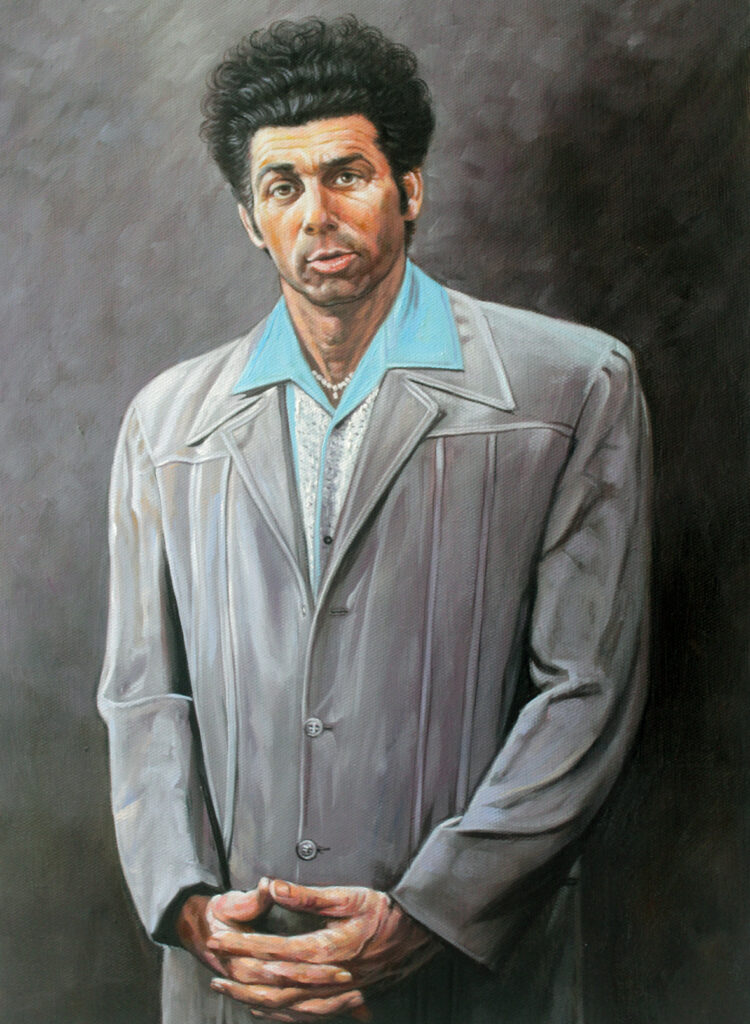

JERRY: She does a lot of abstract stuff. In fact she’s painting Kramer right now.

GEORGE: What for?

JERRY: She sees something in him.

GEORGE: So do I, but I wouldn’t hang it on a wall.

In

“The Letter,” the 37th episode of Seinfield, Jerry’s girlfriend, played by Catherine Keener, is painting a portrait of

Kramer, which inspires this conversation. Did anyone have to explain visual art before 1850 or so? Did explanations become more important than the creative work itself at some point mid-20th century? Jerry is right: there’s plenty happening in a great painting, but there’s nothing to get in the greatest of them, at least in the sense of an explanation.

March 7th, 2020 by dave dorsey

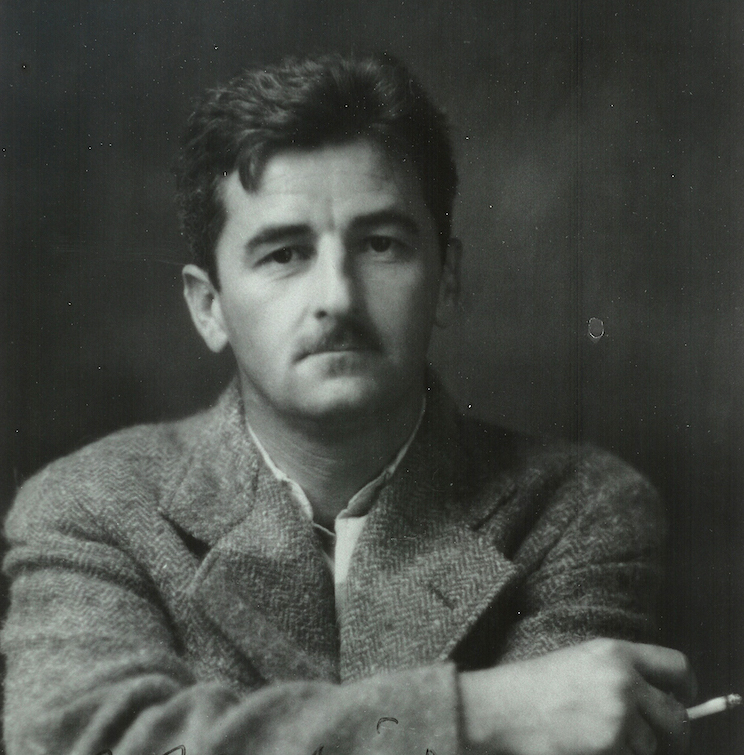

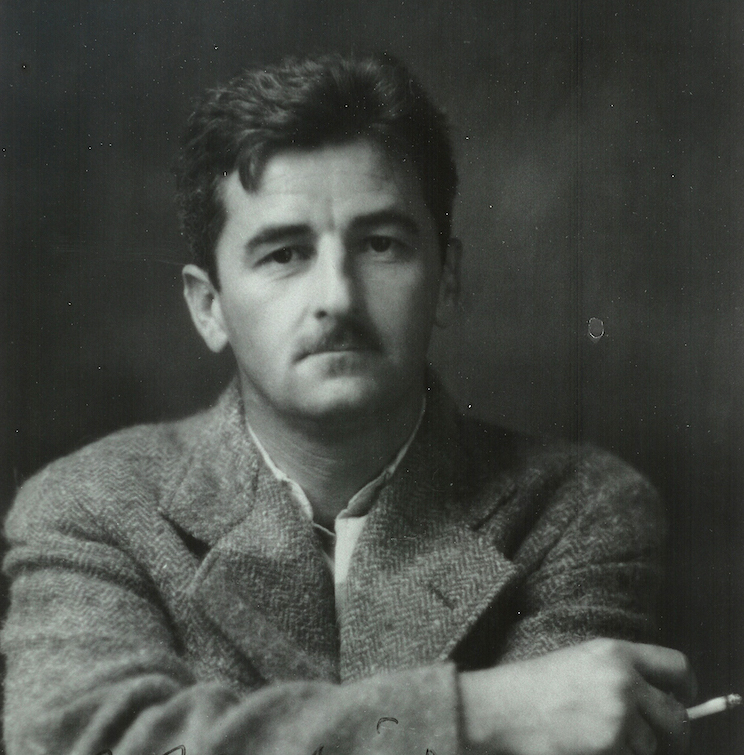

“I write only when inspiration strikes. Fortunately it strikes every day at 9 a.m. sharp.”

That quote has been attributed mostly to Faulkner but also to a number of other writers. It summarizes pretty much what it requires to be professional at anything: habitual hard work. I like the quote because that’s exactly the time I usually sit down at the easel, and it’s when I have the most energy and am also the most critical of what I’ve already done, partly because the sun rises and shines through a window behind me, often striking the canvas directly. There’s no escape from that intensity of sunlight: God’s flashlight, as Larry Miller put it in a slightly different context, though the feeling is the same. Despair and shame at everything so manifestly wrong that felt so right at the time. So 9:05 is when inspiration really strikes. It’s when you ignore everything going on inside you–the sudden urge to remodel the basement, the desire to shovel snow, the ease with which you can now contemplate the emotional safety of bank robbery compared with the struggle of painting–and you pick up the brush. Or the old shirt you use to wipe away a few square inches of still-tacky paint that represent five hours of sub-par effort–and you make merely acceptable whatever looked perfect yesterday and then, around 11 a.m, you actually start spreading paint on canvas in places you haven’t yet defiled. Around 3 p.m. you think, “Damn, I’m good.” Until inspiration strikes again at 9 a.m.