BLM vs. MLK, spiritual art, apple fritters

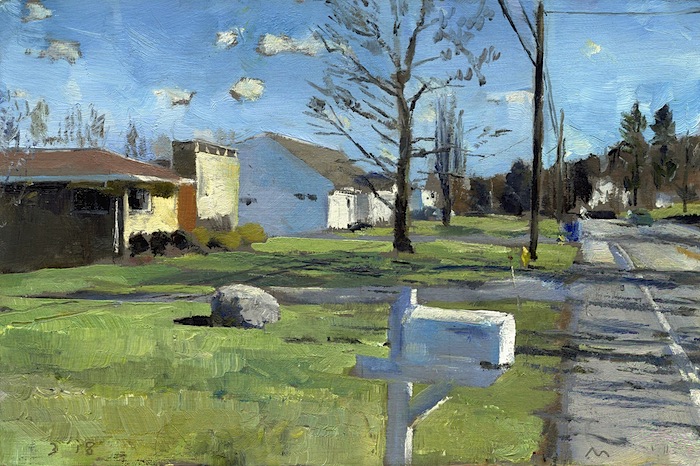

Jim Mott’s painting of a mailbox, after arriving at this spot in his Landscape Lottery.

Jim Mott came by this weekend for a conversation after a long absence, and we picked up more or less where we’d left off last time, talking partly about spirituality, art and God, BLM vs. MLK, his new art project, and some other things I ordinarily don’t talk about, like apple fritters. Though Jim is deeply political, in a way that goes back more to the Sixties than what’s happening now, he’s the least confrontational and least angry political person I know. Many people obsessed with politics seem to have embraced it as a substitute for religion. Jim already has a faith, so politics is simply a way of thinking about how to put that faith into action. What I like about his politics and his religion are the way in which they get submerged into his paint, in a sub-rosa way, neither overt nor strident, producing work that embodies his spirituality rather than illustrates it, if that makes sense. Most of the artists I’m close to are deeply spiritual, but each one in a very different way from the others. Here’s a good portion of our long conversation:

Dave: I went through this spiritual crisis in my teens and it was discovering Van Gogh who got me into it.

Jim: The crisis?

No, he got me into painting. He was so screwed up, but he responded to it by painting. He started by preaching and then went from that to painting, so it was kind of the way he dealt with there being something wrong with the world, or with him.

There’s that romantic notion or tradition that the world doesn’t get it and the individual poet does, so you’re at odds with the world.

It was just the opposite of that with me. I didn’t get it. Life was absurd and I didn’t get it, but that was repugnant to me, so at some level I knew I wasn’t right to have that perception. That was my dilemma. The idea that meaning seemed impossible and this was a crisis, a problem. It seemed the world was pointless and amounted to nothing, and this was horrifying because I couldn’t see out of that mental trap. But there’s a contradiction I didn’t see in this. Camus based The Rebel on a recognition of this contradiction: that people inwardly rebel against nihilism. If nothing matters, then there’s no reason to be dissatisfied with that, just enjoy what you can and that’s that. Why is it horrifying that life seems to amount to nothing? There’s some context in which the absurdity of life is unacceptable but if everything is genuinely pointless how can anything be unacceptable? I couldn’t get to that state of “there’s no way any of any of this can really matter, including my anguish over the impossibility of meaning, so I might as well enjoy life while it lasts.” I couldn’t reconcile myself to this nihilistic certainty I had. So I looked at Van Gogh because I assumed he had to have gone through something like that and responded to it by painting. I’d already been painting pictures of my favorite guitarists, Hendrix, Clapton, Bloomfield. I was in a band, I loved playing my Telecaster. I did the paintings just to have them on my walls. Enlarged copies of album covers. Then I read about Van Gogh and thought, hm, painting is an activity that’s interesting in itself, partly because Van Gogh, this incredibly discontented guy, was so devoted to it. Van Gogh got me to that point. My reading later gave me a way to understand this crisis I’d gone through in a spiritual perspective. So the painting and the spiritual perspective merged.

When you’re doing a good painting you feel like you’re participating in something larger than yourself, at some level it’s about ego-lessness and service. Given all that, the way the art world is all about ego competition and material symbols of success, what would happen if, I don’t know, what happens to you when you buy into that at all. You’re doing what you need to do to advance yourself but, as a result of that, cutting yourself off from your deepest, most authentic sense of what it’s all about – and that awareness of doing something in service to something larger, that awareness and how it imprints itself on the painting, that might be as important to the viewer as all the other qualities that would make a painting conventionally successful.

You mean given the art world’s definition of success. Should you fight it or resist it? That’s always a question.

You’re working to show this . . .

Mystery . .

Right. The art world wants someone who’s world-famous. If someone had handed me world fame, I’m not sure I’d turn it down, but . . .

If it does amount to something, a painting, then if you aren’t known, how do you get it out there? Something essential to your life, how do you connect it to other people?

Even with the significant but moderately narrow level of recognition we get, is it worthwhile to generate a counter-narrative about what it’s all about? As an alternative to the pursuit of the material rewards or even critical recognition. I don’t know. Just to have a small audience to tell that to, you’re still having an impact. Integration is the mission now for me: art and spirit, left and right.

<Behind him on the little end table, I always display his night painting of the Memorial Art Gallery and nearby Tom Insalaco’s painting of an eclair. We have a sidebar discussion of eclairs vs. apple fritters and where to find the best fritters, which was possibly the most impactful part of the entire conversation, but not worth transcribing.)

So what are you painting?