Archive for June, 2021

June 28th, 2021 by dave dorsey

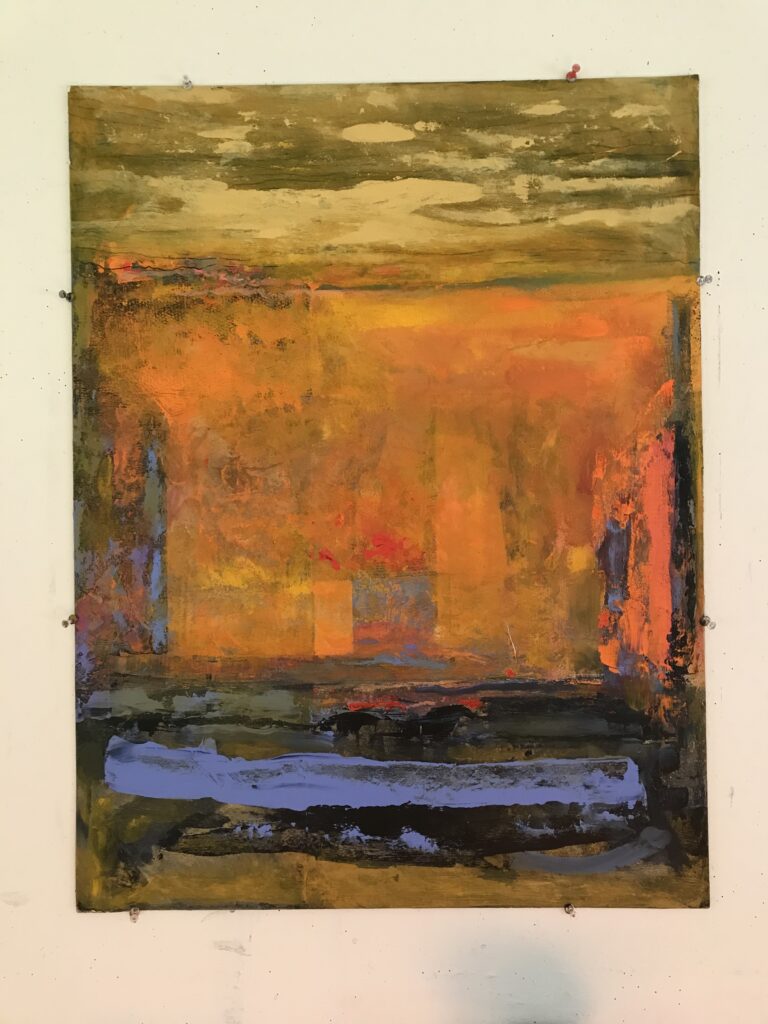

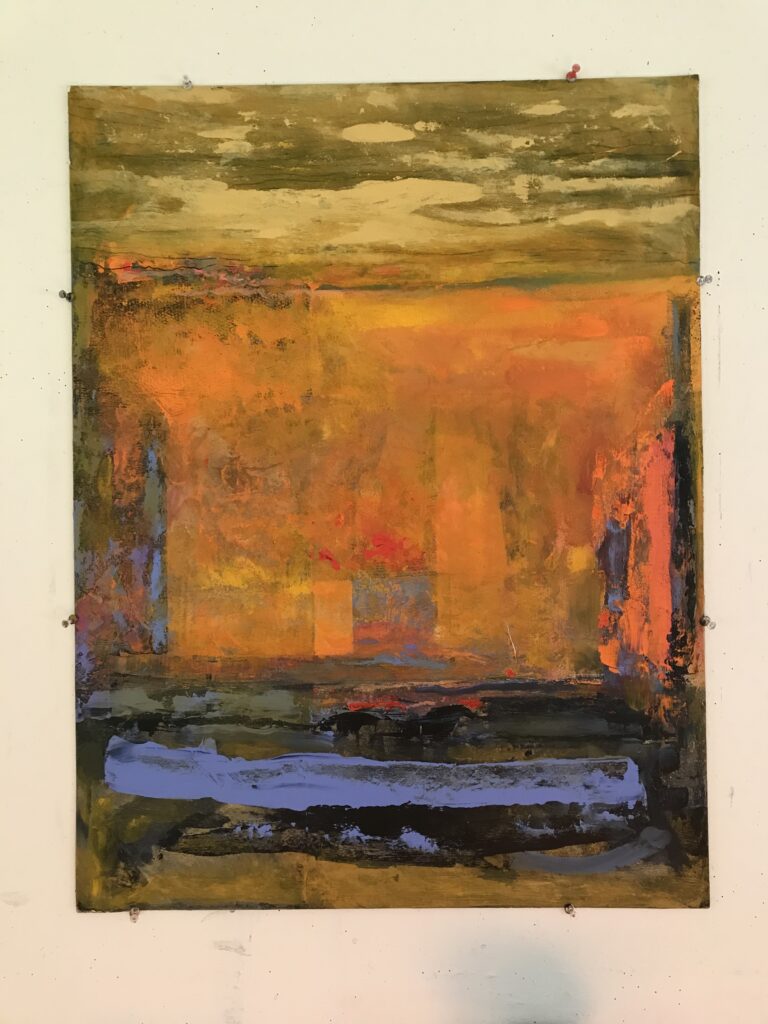

Bill Santelli, Appearance of White, acrylic on canvas at his home

I saw this painting, Appearance of White, completed years ago, at Bill Santelli’s home on my recent visit for coffee with him and Bill Stephens. I was stunned by the mastery of his paint handling here, the restraint of the color, and the rigorous simplicity of the composition. It looks like a visualization of both an internal state of illumination but also simply an evening sky, with the abstract and representational elements so resolutely distinguished from each other, Santelli forces them to wrestle for dominance, the black geometry jutting up from below and also sweeping down across what seems to be a beautifully, naturally executed image of a cirrus-swept evening sky. The long black rectangle, like a squeegee, seems to swipe across the sky from the upper corner, turning that muted purple atmosphere to rusty orange, as if the sun has broken through just at the horizon to immediately tint everything with one last memory of warmth. The angular black voids reach a minor truce with this abstract sky in the bottom right corner, where the sky bleeds into the black and offers a gradual, lovely but precipitous fade into night. The little strip of white, along the edge of that squeegee blade, hints at a greater illumination, and I imagine it takes pride in the fact that the title’s more interested in it than anything else in the painting.

June 25th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Gerard Richter, the Cage paintings.

In the May issue of AEQAI, Ekin Erkan makes an interesting argument against the role of chance in Gerhard Richter’s paintings. He’s responding to an exhibit of Richter’s Cage paintings, a series of abstracts produced according to John Cage’s guidelines for composing music randomly. This sounds like a dry and cerebral exercise, but the paintings themselves are anything but. They’re gorgeous, in large part because, like Rothko, they reach back and employ some of the basic structures of landscape painting and conceal/utilize them in these square fields of smeared, squeegee’d paint. What’s most powerful about this particular series is Richter’s lyrical restraint in the use of color. Deep, rich, and subtle blues and greens peer at you through the gray fabric, the haze, that dominates a canvas. You feel as if you are trying to find your way through a wilderness in the fog, where you get disorienting, tantalizing glimpses of the forest’s beauty, while thoroughly lost. In other words, Richter’s abstraction here seems much more rooted in the the brain’s prehistoric training to look for sky, horizon, land and water, the brain’s predisposition to spot both predator and prey. It isn’t hard to imagine a horizon line across the center of these canvases and see woods, sky, reflections in a lake, evoked by the smears of Richter’s intentionally limited palette.

Erkan seems intent on debunking the role of chance, the “aleatory” element in the production of these, or any paintings, because what evolves in the process of making them has been structured and determined in large part by the rules, conscious and unconscious, the artist observes in the use of paint. This is accurate, and applies even to Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings, which have to be the most random canvases ever produced. But any painter knows how, in its most crucial ways, a particular painting is utterly unrepeatable. The exact proportions of paint in any mixed color will always be subject to the accidents of mixing them in the heat of a session at the easel: there is no way to precisely duplicate anything that happens in the execution at any point in the making of a painting. The Pointillists may have tried. Conceptual artists who simply write out the instructions for the production of a particular work, like Saul LeWitt, might be said to have eliminated chance from the game. Or someone who devised elaborate, scientific guidelines for how to mix favorite colors and how to apply them. Yet ordinary mortals who have only once done an entire painting in one sitting, alla prima, know how magical the process can be when it turns out exceedingly well. What goes into these results, what produces them, remains mysterious: a certain intense quality of attention, a compelling desire, a hunger, to put certain colors in certain ways on a canvas, a certain level of pleasure in the unfolding results that intensifies the desire, and so on, all of which have as much to do with unrepeatable happenstance as they do with conscious control over the process itself. In other words, it’s a state of flow, which is as difficult to achieve as a great painting–they are one and the same, the flow and the outcome of it. Yes, years of practice and discipline make it possible. Yes, it’s the outcome of rules and intentions. But no, it is not without dozens or hundreds of unpredictable and happy accidents, unrepeatable because they weren’t learned and can’t be taught. What’s most crucial in a great painting isn’t the outcome of empirical knowledge and can’t be predicted: otherwise you could teach anyone with a certain level of skill how to make a great work of art. The act of painting can also involve moments of despair when the entire thing seems hopeless and lost only to emerge again in success–by misdirections you find your direction, to paraphrase Hamlet. None of which is predictable. The unintentional results, the moments and outcomes that surprise the artist, as well as the viewer, are what make painting such a life-affirming calling, why it is a quest, not a job.

There’s a great summary of John Cage’s approach in the essay:

What is distinct in Cage, and something difficult but not impossible for a visual artist interested in “chance” to capture, is that in Cage’s “chance” works—e.g., Music of Changes (1951), Two Pastorales (1951-2), Seven Haiku (1951-2), For M.C. and D.T. (1952)—Cage utilizes a compositional tool over which he does not have control. In 1958, Cage introduced his ideas regarding indeterminacy in Darmstadt, Germany, in a lecture entitled “Composition as Process.”[1] At this period of his life, Cage had discarded the ideas and methods underlying his earlier compositions, which had included: numerical structures, considered improvisation, unambiguous notation, and preconceived form. In this lecture, Cage presented his ideas of “non-intention.” In “Composition as process,” Cage lectures on composition that is indeterminate with respect to its performance, remarking that:

“… [t]hat composition is necessarily experimental. An experimental action is one the outcome of which is not foreseen.”[2]

“… [t]he early works have beginnings, middles, and endings. The later ones do not. They begin anywhere, last any length of time, and involve more or fewer instruments and players. They are therefore not preconceived objects, and to approach them as objects is to utterly miss occasions for experience.”[3]

“… constant activity may occur having no dominance of will in it. Neither as syntax nor structure, but analogous to the sum of nature, it will have arisen purposelessly.”[4]

If Cage aims at music which is unforeseen and purposeless, it is because this music is free from the intentions and expressions of the composer’s mind. But this is not something simply left up to improvisation—for one’s “feeling” of being a conscious driver of their artistic process does not mean that they are not acting out of intention, wittingly or not. Thus, Cage implemented models for the realization of this kind of music.[5]

Chance in music, and in visual art, cannot simply “happen” due to the improvisational whims of the artist and their “feeling” of not being in control. It is necessary to provide a mechanism within which it will operate. Thus the composer of a “chance work” or the artist of a “chance painting” must first design some system in which chance has a role to play. A system must therefore provide for certain “givens,” or fixed elements: e.g., collections of musical materials that are to be manipulated, such as the overall structure of the work. This system must have a collection of rules or procedures to be followed so as to produce the final score (or painting), where these rules draw upon the given materials and structures to make decisions based on some random factor, such as the toss of a coin or a computer-generated random number.

Designing the system in which chance has a crucial role in the outcome is not the same as controlling the outcome, nor does it create the other extreme, where the results are entirely random. Painting is a balance between intentions and fortuitous accidents. The optimum spiritual or mental state for an artist to achieve while painting is a perfect balance between what can be predicted and repeated and what cannot–like a surfer staying upright on an enormous wave. What makes a painting strong, up to a point, can be duplicated again and again–what makes it great is another matter entirely. And that factor may not entirely be aleatory, but it can’t be controlled. It’s a gift.

June 22nd, 2021 by dave dorsey

Woman in White, Picasso, oil on canvas, 1923

If you can say what beauty means, then you’ll be able to explain what any great painting means. But, as Iris Murdoch observed, the more clearly you see beauty, or truth, or goodness, the more mysterious it becomes, the more inaccessible to the easy manipulations of reasoning–and the more it becomes something you serve rather than understand and control.

The reactionary, neoclassical work Picasso did after the cataclysm of World War I represents his greatest and most heartfelt struggle to capture what drove him to paint again and again: the beauty and allure of women. He expressed this in so many ways, some far more impressive in hindsight than others. In the neoclassical work, his only showmanship was in easy ability to convey profound gratitude through a series of edges drawn with brilliant, childlike simplicity and proportion. I came upon this example during my visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art recently. Every time I see work like this from the past, I feel I’ve never really fully appreciated it until now, which is exactly how I felt when I saw another example of this period and style from Picasso at my last visit to LACMA . In such a delicate image, I am always surprised, up close, to see how rough he could be in the way he applied the paint, applying it more like joint compound or spackle, smeared, scraped, and generally handled with expedience and no regard whatsoever for how the marks will look up close. Velasquez and Sargent would weep at his heedlessness, and I almost did as well, but not in disappointment. Picasso’s gift was nearly unique, a line as rare as Ingres, but there’s so much more heart here, so much more of a surrender to the essential mystery of what he’s yearning to show you. Beauty like this silences you on the spot, this post notwithstanding.

Anyone who wants to understand Picasso’s comment, sent along to me months ago by Bill Santelli, about the meaning of painting has only to look at Woman in White to understand that a great painting can be utterly meaningless and also the embodiment of everything you most need to see:

Everyone wants to understand painting. Why not try to understand the songs of a bird? Why does one love the night, flowers, everything around one, without trying to understand them? But in the case of painting people have to understand.

From Christian Zervos, “Conversation avec Picasso” in Cahiers d’art, 7/10, Paris, 1935, p. 178

June 19th, 2021 by dave dorsey

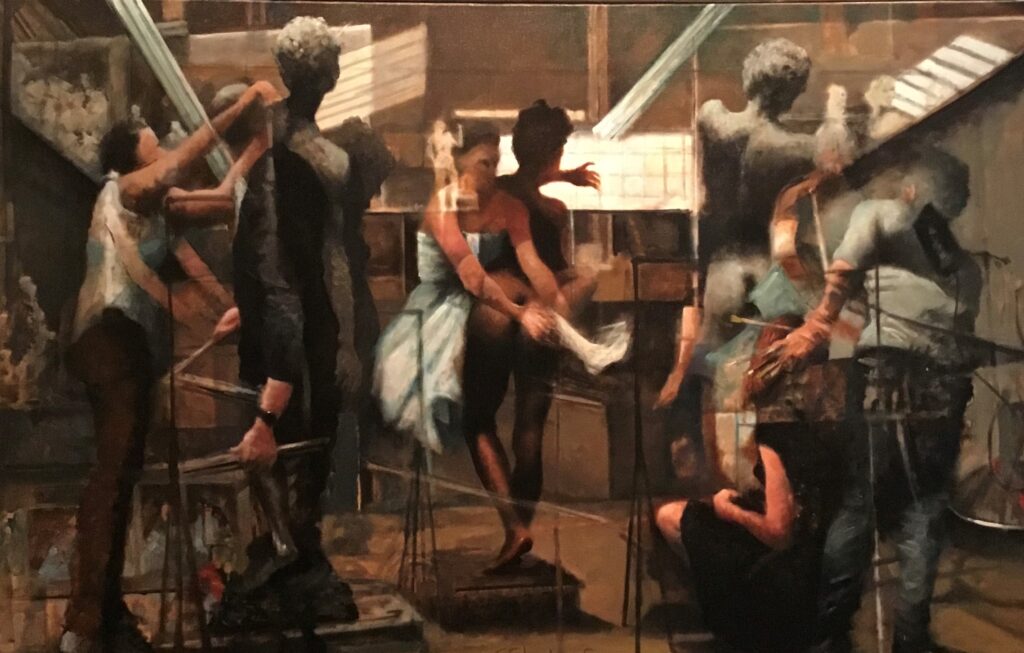

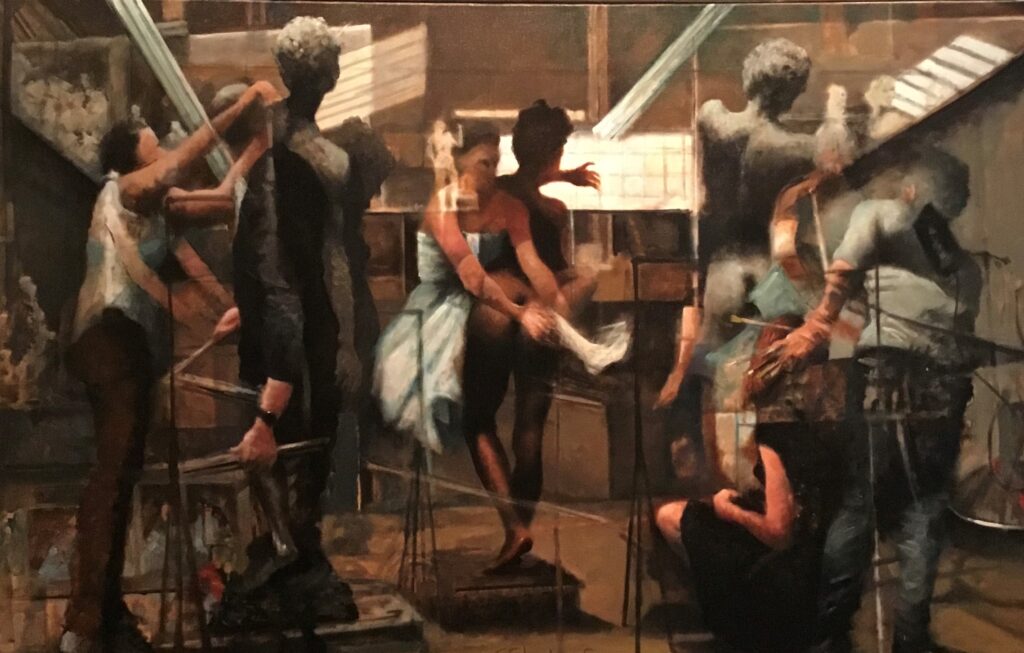

Tom Insalaco, one in his new series of studio paintings

For quite a while now, Tom Insalaco has been working on a suite of paintings that remind me of the world Braque inhabited–both pictorially and spiritually–at the culmination of his career when he was painting abstract images of his studio. Braque spoke in his notebooks about transformation as the essential thrust of painting: to take what’s seen and magnetize paint around the imagery the visible world lodges in your soul. Insalaco has immersed himself in painting after painting of artists at work in various studios, finding sources in films on the Internet and then transforming what he observes into what could be interpreted literally as double-or-triple exposures, scenes superimposed upon one another. But he’s after something outside time and space, indefinable, one’s true life, in accessible to the daily conscious mind. And focusing on the studio as the portal, a window, into this extra-temporal reality, he’s trying to get at why we paint at all. It isn’t to change the world. It’s to witness what’s actually there, everywhere, inaccessible to our chattering, busy minds. Of course, every painter I know and love is trying to do exactly the same thing, but in his or her own way.

Here what appears to be a dancer either stretches or practices in the center of the painting. Layered over this, a remote scene of a performance on stage, a singer or actor, like a remote, lonely puppet, and finally what gives the painting its structural coherence, a studio where two sculptors are working from a nude male model. What’s easy to miss is what appears to be a little quote from Velasquez, as it were: a slightly jumbled hint at Las Meninas, maybe the greatest studio painting in Western art. Insalaco didn’t consciously put that there, but he saw the unintentional reference himself, when I pointed it out. The seated woman in the foreground seems part of the scene with the dancer. Everything melds together into a unity that has its own dreamlike disengagement from familiar time and space, which is Insalaco’s true north, the disorienting transcendence of the surrealists, but closer to Chagall’s ecstatic Cubist-influenced dreams of his love for Bella, his heart’s home, where gravity knocked but never got in. Time here is Proustian, and space is both as small as the amount occupied by a mosquito arrested in amber and as large as the Milky Way.

June 16th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Social Network, Bernard Siciliano, oil on canvas, 2019, 76″ x 100″

I had an exhilarating visit to Manhattan three weeks ago. It’s been a year and a half since I went into the city to see the Salinger relics, as it were, at the New York Public Library. (I have yet to finish a post about that, though it’s nearly done.) The pandemic started a few weeks later and the world seemed to come to a halt. Time stopped. It has restarted. On my weekend in the city, things were hopping, much more alive and back up to speed than I’d thought the place would be. Saturday foot traffic was actually pretty heavy throughout Chelsea and SoHo. Midtown, where I stayed a couple nights, was sketchy and a little weird, as if the idleness of the pandemic drew people into stagnant eddies in alcoves, on corners, everyone just idling in public, harmlessly enough, people discarded by that more purposeful river of humanity to the north and south. Trash everywhere was overflowing nearly every visible container. That New York scene of urine was detectable at regular intervals. A mile uptown, in Central Park and along Fifth Avenue, as well as on the West Side, things seem quietly jubilant and populous.

The galleries were open but not packing anyone in—in other words, back to normal, but with masks. Zwirner had plenty of visitors, but I didn’t want to stick around. Ray Johnson’s solo exhibition was amusing. The motto on the wall as you walked in: “If you take the cha-cha out of Duchamp you get what a dump.” On display in a glass case were some rubber stamps he’d created that made me laugh. With them you could ink some labels onto an envelope or sheet of paper: Collage By A Major Artist, Toilet Paper, Odilon Redon Fan Club. Somebody could make some extra money with an extensive line of rubber stamps in that vein, if people only used paper to communicate now. I spent most of my time at Arcadia, Meisel, Hauser and Wirth, Paul Kasmin and wherever I could find representational painting of one sort or another. Much of what I saw in the galleries I visited was rewarding and, in the galleries I didn’t check out, much of what I could see through the windows seemed clearly avoidable. I caught the last day of the curated group show of figurative painting at Sugarlift, which was the highlight of my weekend. If Sugarlift can make a go of it in Manhattan, after holding its own in Brooklyn, good things remain possible in the world of painting. I rode the elevator up at Pace (what next, an escalator like the ones at Target a few blocks away?) to see the Agnes Martin show, a selection of nearly all-white stripes with only one or two bearing the faintest colors. I felt as I’d felt seeing her retrospective at the Guggenheim. She’s such an enigmatic figure, her abstraction seems intensely personal, cherishing her Platform Sutra, periodically living in isolation, creating one horizontally striped canvas after another, paintings that seem to belong at Dia Beacon next to Robert Ryman. Somehow, though, they are more poetic and wistful, albeit almost as minimal. Why her painting works this way for me, I have no idea, other than the general mystery of painting and what undetectably goes into it and then comes back out. Yet again I was struck by how idiosyncratic her paintings felt, the lines she seemed to have drawn free-hand in graphite to define the stripes, so that the pencil meandered like a lady bug leaving a trail around the little irregularities in the surface, a tiny trickle of graphite (it would appear) that looked serpentine from a few inches away but straight from six feet. Seeing a small collection of her work on view together, the repetitiveness, the sense of slight variations within the confines of a voluntarily apophatic format, gave me courage to keep painting my repetitive images of taffy, seeing where it will lead. (But the work proceeds so slowly, like Issa’s snail. I told Tom Insalaco when I went to see him in his studio last Friday that doing this series takes so much time, it feels like trying to sprint through a swamp.)

My visit to the Metropolitan on Sunday, more than at any previous time, made me feel as if I hadn’t ever understood paintings I’ve looked at many times before, either there or in reproductions. Again and again I thought, I’ve never really seen what was going on in this painting as clearly as I do now. It’s a great state of awareness, to look with that kind of fertile attention, especially in that museum. I spent a lot of my time in the gallery spaces devoted to the evolution of Degas, an artist I’ve begun to admire more and more, though I hardly gave him any attention when I was younger. It was humbling and awe-inspiring to see him grow from a conservative realist to a man who succeeded in getting pastel to do things it hadn’t done before through candid and intimate images of women rendered in long parallel single-hatch marks. But these long lines of color, furrows almost, with the gauzy effect of pastel rather than the crisp marks in a Durer, say, using the tools of drawing or print-making. Those parallel lines that surfaced and receded across the image gave it a vibrating energy, a pulse, that worked in counterpoint to the soft, diffuse light pastel typically gives off. Seeing his transformation from earlier and brilliant academic work to these late, radiant studies drenched in rich color, as I moved from one work to the next, was like watching a caterpillar shape-shift into a butterfly in a time-lapse film.

I had dozens of surprises like that: a Lee Krasner that was reminiscent of Matisse, painted a decade or so before she died; a de Kooning that, up close, revealed that he’d pressed newspaper pages into his gesso, or whatever ground he was using, to leave a ghostly image of the words and pictures pulled from the newsprint, reversed, the way kids once did and maybe still do with Silly Putty; a pair of worn shoes from Van Gogh that reminded me of Heidegger’s famous quote; a vertiginous overhead view of a long table and floor from Sheeler that was part of my inspiration for the series of large tabletop still lifes; one of Braque’s great paintings from his middle period, along with the gueridons, a pool table also seen from directly above, but shaped like an hour-glass; one of the Ocean Parks from Diebenkorn; and maybe my favorite paining from Cezanne, View of Domaine Saint-Joseph, a painting closer to the work of the Impressionists than most of what he did, but with an utterly unique sense of color. He knew how to create a network of marks across a canvas, where every spot of color lives in its own subtle purity, no going-over, no pentimento, once and done, each mark unique—creating maybe the most complex and lovely greens of any landscape ever painted—and yet despite all that energy and perfection in the mark-making, considered on its own, it also serves to convey the humming, brilliant energy of a summer day in the hills. The Metropolitan was full of people. The line for the Alice Neel show was half an hour long, according to the guard. Skipped it, but nice to see things are heating up. All that waiting-in-line patience has been honed by deprivation, probably. On the other hand, the guard told me that shows in the near past have drawn lines that snake out the front door and around the block.

I got the distinct impression that right now might be a rare opportunity for a gallery that wants to open or re-open in New York. For years now, art galleries have had to make more and more money to remain operational in Manhattan. George Billis has left, moving his space to Westport. OK Harris closed a while back, though not simply because of the cost of renting the gallery space. Danese/Corey ended its brick-and-mortar exhibitions, which felt like another Gotterdammerung blow to anyone who longed for islands of sanity and taste in the anarchic and often underwhelming sea of visual art. Five years ago, Steven Diamant packed up and left his gallery in New York to open exclusively in Los Angeles, first in Culver City and then in Pasadena. Both of those locations looked bigger and brighter than the one he’d had in SoHo. He spent five years trying to adapt to California. When I came into the gallery he was in his office, available to visitors as always. I asked about his move back to New York and he said he hated California. I went down the checklist sardonically, after he said he didn’t do yoga. Sushi? Never eats it. Pilates? As if. Charlie don’t surf, and I gather neither does Steve. I found him, as usual, on site in his office, there to answer questions and talk about the show, and his other artists. And this is where he told me some things that ought to signify a little inflection point for the art scene in Manhattan—or maybe a window of opportunity this year, at least. He said that his location is far better than he’d ever had in Manhattan and his exhibition space on W. Broadway at the edge of SoHo is now larger than any space he’s previously had and yet the rent is lower than what he paid twenty years ago.

People should be flocking back and locking in long leases. In major cities and across the country, the real estate mania is driving inflation in housing prices—even as commercial real estate looks more and more like a graveyard for burying cash. The pandemic drove people out of the cities, many of them for good, and is still driving them out, because so many city dwellers learned they can work remotely. Offices are emptying out. The pleasant surprise is that, commercial real estate is getting cheaper. It would seem to be the time to get a deal and open galleries like Sugarlift, dedicated to genuinely good new art, for those who love good art, rather than investors seeking an alternative to precious metals. To put it precisely: do all the gallerists out there realize that this represents an opportunity to move back into a prime location at a much lower rate than before? This undoubtedly won’t last, with all the money the government is pumping into the economy. But, as the city opens back up, maybe some galleries can move back in.

June 13th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Detail from The Healers, Ali Banisadr, oil on linen

After a year and a half of not having crossed a bridge or driven through a tunnel into Manhattan, the most impactful exhibit I saw on my quick tour of Chelsea and SoHo two weeks ago was Ali Banisadr’s work at Paul Kasmin on W. 27th. The Iran-born Brooklyn painter has found a way to tap into the period when European Surrealism morphed into American Abstract Expressionism, and by re-inhabiting that fertile sea change, he’s uncovered something exceedingly rich and strange. In a way, he’s put himself back into the same position as Arshile Gorky, halfway between the two movements, exploring missed opportunities that could have emerged then, using the fulcrum this gives him to create his own eerie and strangely riveting canvases that have more than a little in common with Gorky’s.

Banisadr paints slow-motion and silent battlegrounds or communities of unnatural creatures, the spiritual equivalent of a Star Wars cantina. They’re the sort of beings a feverish child fears or covets in the closet or under the bed at night, little exotic pet-like entities with no recognizable morphology. They don’t look fierce; but they don’t look innocent either. Soft maybe, but not cuddly. They’re too uncanny to completely trust, more like random mutations of a fantasy video game cast or some occult catalog of spirits. It’s as if Hieronymus Bosch had returned and found a new way to embody human impulses as creatures from a weird children’s storybook. Yet there’s none of the repellent suffering you see in Bosch; instead, everything is as quiet and lovely as life in a tropical fish tank under black lights.

The Healers

These scenes lure you with the pleasure of their silky transitions from one rich color to another, the energy of their execution, the velvety quality of the paint that looks as if the support itself is plush and black. Everything seems to emerge from that black ground. What you see at first is just the quality of the paint—smeared, speckled, striped, MORE

June 10th, 2021 by dave dorsey

Lacoon, Julio Reyes, egg tempera on panel, 16″ x 16.5″

You have a few more days to catch the exhibit of egg tempera paintings from Julio Reyes at Arcadia on W. Broadway in SoHo. They are well worth the visit. He has an ability to use figurative painting to convey internal states of mind and heart. He searches for objective correlatives, as T.S. Eliot referred to the poet’s quest, for these complex internal worlds. Some of his oils are included in the show, but mostly you’ll see his recent efforts in this medium that’s been around far longer than oil. Steve Diamant, who is almost always at the gallery when it’s open and ready to offer commentary on the artists he has chosen to represent for years–the old-school way– shook his head with admiration when I asked about the process. He said it’s arduous, time-consuming and requires the building up of an image through many coats of paint, mixed from pigment and raw egg yolks. The medium was used by artists as diverse at Botticelli, Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. Up close, the mark-making is a marvel. It’s essentially an impressionist technique, where Reyes builds up his forms through thousands of repetitive marks, but each one has its own distinctive and precisely defined shape. The images are luminous, dreamlike and suggestive of heightened states of perception and feeling, and the workmanship is masterful, personal, fully-realized.

shook his head with admiration when I asked about the process. He said it’s arduous, time-consuming and requires the building up of an image through many coats of paint, mixed from pigment and raw egg yolks. The medium was used by artists as diverse at Botticelli, Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. Up close, the mark-making is a marvel. It’s essentially an impressionist technique, where Reyes builds up his forms through thousands of repetitive marks, but each one has its own distinctive and precisely defined shape. The images are luminous, dreamlike and suggestive of heightened states of perception and feeling, and the workmanship is masterful, personal, fully-realized.

June 7th, 2021 by dave dorsey

New work from Bill Stephens

I sat down last week with Bill Stephens and Bill Santelli, outside Santelli’s home studio near Powder Mill Park. We talked for three hours about many things including my exhilarating recent visit to New York, and their work. I saw one older painting from Santelli hanging on his wall that knocked me out–I’ll post it next. Stephens sent me these two recent pieces, continuing evidence that he and his wife, Jean, are the most experimental painters I know at the moment. Their work continues to morph into new areas, sometimes gradually, but also abruptly and unpredictably. These two acrylics by Bill are marvelous in entirely different ways, the one Rothko-ish and the other drawing comparisons to Monet from Santelli. Yes, if Monet had been at the bottom of his water lily pond looking up toward a sunny sky . . .

shook his head with admiration when I asked about the process. He said it’s arduous, time-consuming and requires the building up of an image through many coats of paint, mixed from pigment and raw egg yolks. The medium was used by artists as diverse at Botticelli, Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. Up close, the mark-making is a marvel. It’s essentially an impressionist technique, where Reyes builds up his forms through thousands of repetitive marks, but each one has its own distinctive and precisely defined shape. The images are luminous, dreamlike and suggestive of heightened states of perception and feeling, and the workmanship is masterful, personal, fully-realized.

shook his head with admiration when I asked about the process. He said it’s arduous, time-consuming and requires the building up of an image through many coats of paint, mixed from pigment and raw egg yolks. The medium was used by artists as diverse at Botticelli, Thomas Hart Benton and Andrew Wyeth. Up close, the mark-making is a marvel. It’s essentially an impressionist technique, where Reyes builds up his forms through thousands of repetitive marks, but each one has its own distinctive and precisely defined shape. The images are luminous, dreamlike and suggestive of heightened states of perception and feeling, and the workmanship is masterful, personal, fully-realized.