I’m a painter, right?

Being a painter generally means feeling like an object of curiosity or affectionate sympathy—I do admire his work, love the guy, but how does his wife put up with him? Sometimes I think I’m looked upon with vague suspicion, as if my street’s property values will immediately edge down if word gets out about what I do with my time. Making a painting doesn’t strike most people as work. It’s fundamentally irresponsible, usually requiring other sources of income, and is essentially a strenuously sedentary form of play. Like, say, high-stakes poker. No sweat is involved, but money can be made, though not very often and only by a few of the luckiest practitioners.

There are other problems. Those of us who devote long hours to the act of painting tend to hang together, forming little suspect coteries of marginality—grown men and women who want to make pictures, dress in age-inappropriate ways, or gender-inappropriate ways, or species-inappropriate ways, and usually earn less than enough to make ends meet. We look at one another and think, yep, she has the disease too, thank God, because it means I’m not alone. I see Richard Dreyfuss sculpting a mountain with his mashed potatoes at the dinner table in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, as his children weep with the conviction that daddy has gone bonkers, and I say, Keep going, keep going, Roy, it will all make sense in the end! But I wonder. Will it? So I hang out with fellow artists and drink beer and talk about how badly other people handle their paint, or how amazing Richter is when you see his actual canvases, or how so-and-so is a clever sell-out—and in the end we go our separate ways and feel more energized, but just as alone. Because the solitude is essential, even if sometimes intolerable. You have to isolate yourself and work on self-imposed deadlines for a solo show where months or years of labor may go up and come down with only one or two sales, no reviews, and maybe much less praise than you’d hoped to get. And then, after these necessary bouts of doubt and loneliness, you rush to hang out with other artists again and talk your way toward 3 a.m., hoping that the friendships will support you, emotionally, until you arrive at a breakthrough.

And that’s how a few years of painting stretches into many years, and then decades, at which point you start constructing elaborate philosophies on why it matters that you keep trying to build something beautiful even though only a tiny percentage of the human population may ever see it. I had lunch with a good friend from college after decades of estrangement, and I told her I was writing a blog in part to clarify for myself why painting matters. She smiled tolerantly and said, “Isn’t it just that you really want to do it?” True, but I didn’t need to hear it put quite so bluntly. Especially at my age.

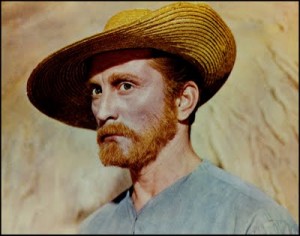

So I think it’s fair to ask, what is wrong with us? Especially male painters. Why can’t we just be ordinary guys? Another friend of mine, an amateur photographer said, “I think Average Joe generally thinks of painting in an almost comical way. Ernie Kovacs with a beret dabbing at a canvas when the inspiration strikes, or Kirk Douglas cutting off his ear. Angela Lansbury relaxing by sitting at an easel near the sea. Women should be doing it.” Or that unbalanced gay brother in Wedding Crashers. We aren’t immune to the way we’re probably viewed by business executives and wild-catters and truck drivers and most guys who do nothing but guy things. If you’re one of the celebrated elite painters, none of this applies: you have a house on Long Island and a place in Maine and a wife who also makes art, and you probably have a studio in Europe, as well as a fleet of fun vehicles, and you get to fly around the world to attend parties where people buy your work before the opening. In other words, you’re a one-percenter. But most painters will never get a glimpse of that easily defended life. Most of us have to explain what we do to people who secretly look upon it as self-indulgent and basically a potentially enriching hobby, like collecting Depression glass. The world won’t miss a new painting if it doesn’t get painted. No focus group has been crying out for it. So why do it? If you can clearly explain why a Chardin still life matters, please speak up. It does. But all the reams of what’s been written about art won’t really explain exactly why. Some individuals whose opinion I value think a man my age should have a punishing job, like most people, who work long hours every day for an organization that will insure my teeth and enable me to be a productive member of the social order. They may be right, but I’m more inclined to reread Walden and study the stoic economics of Thoreau’s retreat, and then head toward the nearest cottage by a pond (with a box of paints and brushes).

My opinion of myself varies greatly, from one day to the next. On Thursday, I’m thoroughly convinced that this odd pursuit of applying paint to one kind of surface or another matters more than anything else I could possibly do with my time. On Monday morning, I’m utterly convinced that I’ve wasted crucial years of my life. Then I crave recognition or just sales to restore my convictions about the importance of visual art. Even though the value of it resides in whatever mystery imparted itself to the silent gaze of the thousands around me at the Metropolitan Museum when I visited it this past week on a Tuesday.

Actually, I’ve had more than enough recognition to keep doing this. I’ve won a few awards. I’ve been accepted into prestigious shows. I’ve had my work published in full-color catalogs. I’ve had my writing about art published as well. Yet, none of this recognition and achievement registers within Average Joe’s idea of hard-knock reality. I remain an obscure laborer in this field—only one among the countless many. I continue to make most of my money as a writer and rely on my wife for her income as a teacher. Painters are seen as willful egotists, mavericks, visionaries, rebels, misfits—in other words, talented, self-involved assholes. Yet, in reality, the pursuit of excellence in paint represents a long and difficult curriculum in humility, an ability to live with no illusions about one’s importance in the world, an assurance that you are here to do something potentially wonderful that will go almost entirely unacknowledged, like the song of a wood thrush in an uninhabited region of Canada. The thing is, I’m fine with that, at least for now. But of course I am. I’m a painter, right?

When I was sitting there in an interview, a graduate from an excellent business program, I was thinking about a quote from Robert Travor. Travor was the pseudonym of Michigan Supreme Court Justice John Voelker, with whom I share in another obsession, trout in rivers. If you substitute art for all things fishing and river related, the quote explains some of my choices.

“And finally, not because I regard fishing as being so terribly important, but because I suspect that so many of the other concerns of men are equally unimportant and not nearly so much fun.”- RT

Ultimately, I realized all the other things I was being pushed towards weren’t any more important.

Full quote-

“I fish because I love to. Because I love the environs where trout are found, which are invariably beautiful, and hate the environs where crowds of people are found, which are invariably ugly. Because of all the television commercials, cocktail parties, and assorted social posturing I thus escape. Because in a world where most men seem to spend their lives doing what they hate, my fishing is at once an endless source of delight and an act of small rebellion. Because trout do not lie or cheat and cannot be bought or bribed, or impressed by power, but respond only to quietude and humility, and endless patience. Because I suspect that men are going this way for the last time and I for one don’t want to waste the trip. Because mercifully there are no telephones on trout waters. Because in the woods I can find solitude without loneliness. … And finally, not because I regard fishing as being so terribly important, but because I suspect that so many of the other concerns of men are equally unimportant and not nearly so much fun.”

― Robert Traver

Awesome Rick. Really well put.