Selling isn’t always selling out

One of the hardest balancing acts for anyone who has found any sort of market for creative work is how much to keep pursuing work that has a chance of selling. In other words, how much should anyone purposely create work that is likely to sell, simply because it will sell. That last phrase is crucial. Part of what this activity involves is forgetting the wisdom of Yogi Berra, which was the content of my previous post. Doing great work means taking on a challenge where what you know how to do isn’t enough–at some point it doesn’t avail. When money beckons, the temptation is to settle into routines you do know, and though the results may be desirable to a buyer, the artist who’s honest knows that something lifeless has been passed along. (What’s so distinctive about painting for me is how it requires me to do things I don’t know how to do, and how the act of painting, like a golf swing, involves things that can’t be stored away as knowledge. The learning, if it’s there at all, happens in your body and your subconscious. Painting well is more about unknowing.) I’ve been finishing up a commissioned painting, a second version of a painting I sold several years ago–at the request of a family member who wants to buy it. I got this request early this year and have been procrastinating for months, partly in the interest of completing work I wanted to enter in the Rochester-Finger Lakes Exhibition this year, but also because I wasn’t sure I wanted to put in the weeks required to complete what will be nearly a duplicate of a previous painting. With my other work done, I had a choice between doing this repeat performance or creating a series of smaller paintings, which I have also been postponing for well over a year as well. (There’s a lot of procrastination up in here at Casa Dorsey. . .)

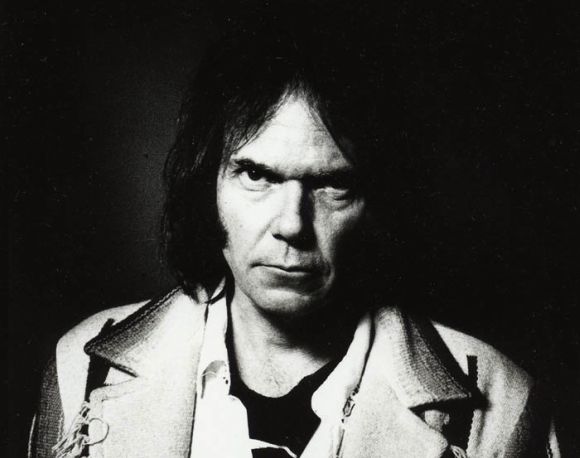

Walt Thomas, a friend who sends links to stories that occasionally inspire my posts, emailed me a link to this story about how David Geffen once sued Neil Young for not trying hard enough to be Neil Young. He’d started recording music that wasn’t typical of his past work–in other words Geffen had invested a significant sum in luring Young to his label, and he wanted Young to deliver the sort of material he’d been known to write and perform. It’s a great article, because it gets to the crux of this issue about what constitutes “selling out”, which lies close to so much of the criticism about the art world today, which centers on how money can corrupt what visual artists produce.

What interests me is when and why an artist should refuse to do work that would be more likely to sell compared with other work that might, say, get more approval from critics or other artists–but never sell. I got around this quandary, when I started this current commission I’m doing, by realizing that I was eager to paint this image again because of the pleasure involved in making it appear on the canvas, not for the money, which I don’t immediately need. I wanted to do it partly because I know how much my patron loves this image and wants to own it, and partly because I actually love the process of painting it. It’s a commercial pursuit in the sense that I’m doing it primarily because someone is paying me to do it, and wants the painting more than anything else I might produce right now. Yet it qualifies as a legitimate effort, in my view, because it’s one of those paintings where my level of skill, my predilection for certain colors and textures, and so on, fits perfectly with the challenges of the work, making it enjoyable and something of an end-in-itself. If you love making the image, I don’t see how the work can be dismissed as meretricious–commercial, in the pejorative sense. The ideal, of course, would be to find a way of making pictures that bring a sense of deep satisfaction to the artist while making them, only to find that these are precisely the pictures that sell. I’m showing a still life of a skull at the Memorial Art Gallery right now which is about as anti-commercial an image as there is. Few people want a classic vanitas image on their wall. Yet it was deeply satisfying to paint. So it works in reverse as well: if the satisfaction and fulfillment are there, I pursue it, even when I know it means the time I put into it won’t be generating income. So I guess I’m saying if an artist feels a sense of satisfaction in the act of painting, purely for its own sake, the work of art is worthwhile, regardless of its marketability.

Which feels right, but shouldn’t the painting’s marketability actually be part of what makes it good? Shouldn’t people want to have access to it? That’s a question Dave Hickey would love to answer, but I’m not sure I can.

My next project will likely be something just as commercial in a way that will put me at odds with fellow artists who think I’m wasting my time with them: a series of small oils of cupcakes. I’ve been extremely ambivalent about painting more cupcakes, even though I sold a mid-size one for a good price at my last Oxford Gallery show. They haven’t seemed challenging enough, even though a cupcake is actually not an easy thing to capture properly. The problem is that a cupcake painting seems nakedly commercial in the worst sense: it feeds on a superficial craze for cupcakes that doesn’t seem to be abating among those who can afford to buy and serve them. It’s a frivolous subject, if not the most frivolous imaginable. Yet I’ve painted large images of jars full of jelly beans, which occupy about the same sort of cultural zone as cupcakes (don’t they?) but the way in which a jar of jelly beans can solve formal challenges–how the image balances abstract with representational properties and how it enables me to improvise with color–justifies a painting of them in a way that’s harder to justify with a cupcake. What helped me break through my reservations about the cupcakes was seeing an ad for them in a local literary magazine, Lake Affect, which I was given because it had published my still life of radicchio as an illustration for a story about buying local produce. The photograph of the cupcakes from Baker Street Bakery offered the sort of color that I wanted, while other cupcakes I’ve been able to buy locally have been mostly earth-toned. Finally, I’ve found a way to use color the way I want while painting . . . a cupcake. So I bought a dozen, photographed them, and I plan to use nine of the shots for a series of triptychs. So I’m back to being an enthused advocate for cupcake paintings. I love Thiebaud. I love Emily Eveleth. If Manet had painted a cupcake, it could easily be hanging at the Metropolitan. I rest my case. It isn’t what you pick as a subject, it’s how you paint it. And if you paint it well enough to sell, it seems to me that’s exactly how it ought to work. No?

My family was in town fro Elizabeth’s wedding this weekend, and many wanted to come visit the new studio, mess that it already is. It was a chance to show them a couple of the new landscape pieces in person, and I got a very enthusiastic response. But maybe even better for me was the response to the bear paintings from my son, an art student, and my niece, an art history major. Both got right in my face about my not trusting the impulse to do them, told me they were as serious as anything I’m doing, and get after it.

Yet another lesson in putting aside self doubt and self deprecation. To plagiarize Nike, Just do it.

Well put, Rick. It’s so great to get that kind of reaction from people you trust. I love the bear paintings. It’s a way of working with organic shapes, while the barns give you a geometric format. There’s a polarity in those two motifs you could work with: ones still and angular, the other kinetic and curved. Love to see some big bears. My fanfar recently about boldly tackling cupcakes has been humbling. For some reason, my approach isn’t right, with only one exception. I did learn a couple things about handling paint with the one that worked, but the others weren’t instinctive enough. So I’m putting them on hold, though I’m not giving up. I’m going to try what I was doing with some candy jars instead. Meanwhile, I’m also doing my usual stuff, which is rewarding as ever.

One thing more related to what you described here: for many many years some of the most enthusiastic response I get is from blue-collar workers who come into my house or my parents’ place (which is full of my stuff of course) and the workers almost always stop and ask about the paintings and look at them with pleasure. Plumbers, installation guys, electricians, you name it. They actually notice and stop and look. Yesterday two guys showed up with a countertop Nancy ordered for a bathroom and on the way up the stairs the tall guy says, “Wow. That is great.” Then when he saw a second and third candy jar, “I’m going to hazard a wild guess. Somebody’s a painter here.” He kept checking them out as he came in and out. One time a worker actually asked my parents if a small still life was for sale and for how much. It’s so gratifying (but also kind of sad that art can’t be priced so that someone like that guy could buy it), but what I love is that I’m doing work that communicates to nearly anyone. So much art is created specifically to communicate with only a tiny slice of the art-viewing public. Your work does that as well.