Remembrances

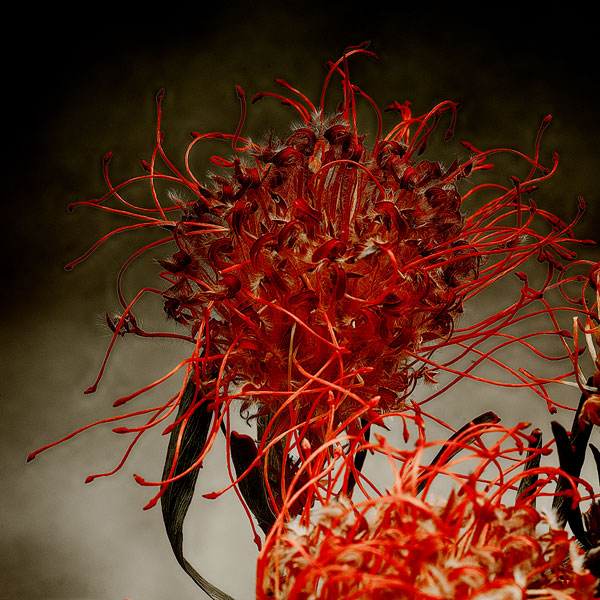

I’m eager to see Alan Gaynor’s solo show at Viridian Artists, starting this week: his shift toward the organic forms of these wilting flowers struck me as different from all of his previous work when I first saw them. All of his work is personal, but there’s a depth of feeling and vulnerability in the new work that’s arresting. His earlier shots of architecture reflected the passion he’s invested in four decades as a successful New York architect, yet the flowers are a shift toward something more intimate and unruly. He started taking this series while his wife was dying, and the gravity of his inspiration comes through in the beauty he finds in what are essentially leftover decorations, ready to be tossed out. His opening reception is tonight at Viridian. I talked to him a few days ago about his work:

Alan Gaynor: When I was in architecture school I took a photography course because I thought I didn’t know how to photograph, and I thought I should at least be able to take vacation pictures. I studied with a woman who gave us an assignment to take a roll of film, back in the day of wet developing. We’d shoot it and develop it on our own and come in with contact sheets. I did two rolls because I’m an overachiever. This was in 1969 maybe. I came back with my contact sheets and she looked at me in front of fifteen people in the class. She said Oh my God, do you know Eugene Atget’s work? I said, “I have no idea.” She said, “You should look it up. These are wonderful.” That was the beginning. I photographed all through college. I graduated from 35 mm to 4 x 5 and I shot 4 x 5 black-and-white film for years. I put it down since starting and growing this business was a double-time job. About twenty years ago I picked up the camera again and again started shooting black-and-white because I didn’t know how to process or print color. It was too difficult for me. I set up a dark room and started taking courses with people like John Sexton who was an apprentice to Ansel Adams for a long while. With some people who were very large names and from every one of those people I learned something. I started shooting buildings and cityscapes. Then I got interested. My son is seventeen and he was a subway freak since he was four years old. He had a real wanderlust as a child. I began to appreciate the subways in a way I hadn’t before. I stopped and started looking at them. I had to get a pass from the MTA and set my camera up, but I still got my chops broken by the police but that was OK. They’d let me finish the shot and that’s all I cared about. I had a pass but you don’t want to argue with them. I’d beg them to let me finish the shot. I shot some landscapes for a while. I switched to digital.

DD: That would make color possible.

AG: It made color easy but black-and-white difficult until I learned to convert to black-and-white. I love Indian architecture, Islamic architecture. I started doing these panoramas from mid-level up in buildings. Those were taken knowing exactly how they were printed. A city you experience as a layering of buildings not individual architecture. The layering of one thing on top of another on top of another on top of another. Those panoramas were designed to express that. Then during this period my wife got very, very ill.

DD: I think that’s a big factor in what’s going on now in your work.

AG: It’s a very big factor. The first flower shot I took were tulips I bought for her. They were her favorite flower. As they were dying, she was dying. After that I started photographing half-dead or three-quarter-dead flowers sort of as a tribute to her but also to work it out as a photographer.

DD: Those are fascinating. The first of your work I saw were the panoramas that seemed very controlled, not that these aren’t controlled, but they’re opposite in the quality of line, the color . . . it’s all controlled in the way you frame it. You’re setting it up no matter what you shoot.

AG: The thing about photography, it’s all about framing. I take very few photographs. It’s extremely deliberate. The camera is something I use to compose; it’s not random. It’s why I don’t do street photography. I don’t do people. I look at someone like Walker Evans who did both that and the sort of things I do. He did lots of different things. I’m only interested in the composed; not the accidental or photographing people doing wonderful things or funny things. Not that I don’t like people, it isn’t what I’m interested in photographically.

DD: Gary Winogrand, for example.

AG: He’s a very fine photographer. But it isn’t random. Everything informs what you do. My being an architect informs what I do even when I’m photographing flowers.

DD: With the flowers, the whole situation with your wife is there in those pictures and other people wouldn’t take them that way.

AG: They wouldn’t see the beauty in dying flowers. I don’t know who else shoots dying flowers; not that I was looking to do something nobody else was doing. Part of the democratization that the camera gives is that anybody can click a button but not everyone can see or compose; not everyone sees the shot in front of them. It isn’t a matter of putting the camera on automatic and walking down the street.

DD: Describe for me how you do the flowers.

AG: It’s very simple. I wait until the flowers get to a particular state and then use a relatively diffuse overhead light only. I shoot against a seamless gray background most of the time. I started out using a Canon 5D Mark II graduated to a Hasselblad with a macro lens. It’s a lovely piece of machinery. I have an Arca Swiss view camera with a digital back. My camera of choice is the Hasselblad. I have an older one that will take a 39 megapixel back with a proper mount. Hasselblad lenses are wonderful. It’s certainly not a consumer camera. When I shoot architecture with my Canon I go nuts trying to correct the distortions. The lens distortion. Canon lenses are wonderful but it’s not a Hasselblad lens or a Leica lens.

DD: You get curving lines?

AG: Yes. Barrel distortion. The Haselblad lens is much higher quality. The panoramas are done on a 6 x 9 view camera with Rodenstock or Schneider view camera lenses, with a sliding back that allows me to stitch together three or four shots. Those are wonderful lenses. If I set the view camera right I don’t get distortion. It’s a lot of the work, and it has taken me years to learn. There is a lot of work I couldn’t do. If you took me to a photo studio, I would not be able to shoot products.

DD: That has a lot to do with lighting.

AG: Yes, and I use very rudimentary lighting.

DD: Are you reflecting off a white surface?

AG: No, it’s direct light. It’s being filtered through a shade-like material. I shoot on my dining room table, frankly.

DD: Do you use a full spectrum bulb?

AG: No. In Photoshop the gray is gray, or some other color I want. A lot of it is post-production.

DD: You have to get depth of field right though.

AG: You can do focus stacking. With RAW files, it allows you—I haven’t done it yet—but it allows you to stack focus. You shoot ten RAW files, each one is focused at a different depth.

DD: Like HDR, for exposure.

AG: Yes. A lot of what I do is post-production.

DD: When you pick these flowers, are you picking them specifically for the photographs?

AG: I have a friend who works for a commercial florist and I pick up her dead flowers. After an event, I get the flowers.

DD: That goes with the whole feel of what you’re doing with the shots. They’re almost like found objects.

AG: Either I take them or they go into the trash, or the compost if we’re being ecologically responsible. I feel like I’m getting to the end of the flowers, but I don’t know. I’m so involved in the architectural business, with the move to the new location, I’m not sure.

DD: How long has your firm been around?

AG: This is our fortieth year. In ’75 I decided I needed to be in Manhattan. I was in Brooklyn at the time. For $85 a month I had a full floor of a brownstone.

DD: That’s amazing.

Comments are currently closed.