Reverence for the everyday

The Mezzanine is one of my favorite novels, which is why I like to think of Nicholson Baker as a Rochester homeboy. The entire novel took place on an escalator that once existed downtown here. From the intro to an interview with Baker in The Paris Review:

The Mezzanine is one of my favorite novels, which is why I like to think of Nicholson Baker as a Rochester homeboy. The entire novel took place on an escalator that once existed downtown here. From the intro to an interview with Baker in The Paris Review:

Few other authors would notice, as Baker did in The Mezzanine, that late-twentieth-century American men trying to pass through a door at the same time always say “oop” to each other instead of “oops.” After some twenty-five years of writing, Baker’s reputation is as unusual as his work. He has been praised, widely and enthusiastically, for his style, humor, originality, and empathy. (As Martin Amis once put it, “Throughout his corpus there is barely an ordinary sentence or an ungenerous thought.”) At the same time, some critics have very publicly loathed a handful of his books, most vociferously Vox(“tedious”), The Fermata (“repellent”), Checkpoint (“scummy”), and Human Smoke(“childish”). Many of Baker’s talents are self-consciously small: meticulously inventive phrasemaking, a masterfully intimate tone, and a superhuman gift for observation. He has a Dutch-painterly reverence for everyday rituals and objects—a belief that they will start to glow with significance if we only pay close enough attention. This has left Baker open to the charge that the work itself is trivial, quaint—a bubble of old-fashioned belletrism floating through a harsh modern world. (Leon Wieseltier, writing in The New York Times, once called Baker’s novels “creepy hermeneutical toys.”)

What’s disguised by Baker’s cheerful tone, however, is his passionately sustained conviction that we should honor the details of our lives rather than getting carried away by projections and abstractions. In this quest, Baker has seemed continually willing to risk puzzling his fans and inflaming critics; he has shown an indifference to publishing fashions that few authors could have sustained. One index of this independence is that, although Baker has been published for his entire career in magazines such as The New Yorker and The Atlantic, he has never held a staff position. “I felt I had to be someone who would leap in from outside,” he told me, “and do some nutty thing and then run away cackling.”

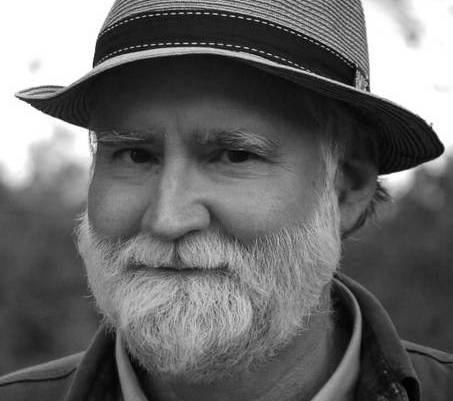

Baker is fifty-four years old, but you can still see the teenager in him: he is self-consciously tall and shy, and his face turned red, often, when we talked about his books. He lives in a rambling eighteenth-century house on the border of Maine and New Hampshire. We spoke there for several hours, first in the kitchen and then in the living room, next to the fireplace in front of which he wrote A Box of Matches. Later, Baker drove me to a restaurant in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where, as we entered, a man exiting at the same time very distinctly said, “Oop!”

Comments are currently closed.