Coontie hairstreak, stinky leafwing, yucca, snout, et. al.

A New York Times review of a book about butterflies and moths, unfinished and never published in its author’s life, sounds as if it’s worth a look. I see there will be illustrations of leaves in it. I’ve been laboring with the job of rendering peony leaves in oil paint over the past couple weeks–it might do my morale good to see how someone else succeeded or fell short in the effort. But I’m interested in this fellow’s project on its own merits. A few days after my wife and I moved into our little A-frame-like gingerbread house in Utica, New York, back in the 80s, we found a cecropia moth slowly fanning its wings on a rock in the little overgrown garden left behind by the previous owners. It seemed more animal than insect. With wings spread, it was as large as my hand. The symmetrical patterns in those scaled appendages, intricate and abstract, looked like eyes or planets. And this, in turn, reminds me that I have yet to write a full response to the fantastic retrospective of Emmet Gowin’s photographs at the Morgan–this book of lepidoptera coincidentally echoes Gowin’s humble, obsessive two-decade photographic pursuit of butterflies and moths in South America.

The book described below, The Butterflies of North America, includes the drawings by a fellow artist/observer, Titian Peale (who seemed to be named after two earlier artists.) Anyone who undertakes any artistic project that stretches over decades is automatically interesting, yet the names of his winged insects alone are a treat:

. . . you’ll discover the Mexican dartwhite and the Pacific orangetip, the yucca and the duskywing skipper, the coontie hairstreak and the sunset daggerwing, the stinky leafwing and the patch checkerspot — not to mention the Eastern comma and the mourning cloak. There are moths here, too: the yellow-necked prominent, the white-marked tussock, the satellite Sphinx and the snout.

The book, unfinished and unpublished when Peale died in 1885, represents more than 50 years of work. The manuscript ended up in the rare book collection of the American Museum of Natural History, where it somehow languished after it was donated by a family member in 1916. All of Peale’s artwork and some of his field notes from the manuscript are being published next week as “The Butterflies of North America: Titian Peale’s Lost Manuscript.”

Peale, who spent much of his life as an assistant examiner with the United States Patent Office, could never have lived up to the original title; there are, after all, several thousand species of Lepidoptera in North America. But what he did leave us is revelation enough.

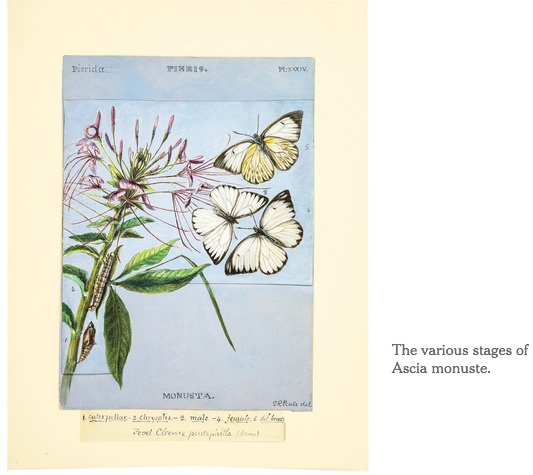

“Butterflies” features more than 200 works of art — in gouache, watercolor, ink and pencil — that through Peale’s sharp but sensuous eye show the life cycle of moths and butterflies, from egg to caterpillar to pupa to winged adult. These striking illustrations are complemented by notes, studies and sketches in Peale’s hand from his field books.

Peale “considered scientific description and graphic representation entirely commensurate and complementary modes of attention to the natural world,” the art historian Kenneth Haltman writes in the book’s biographical essay.

Each caterpillar, often paired with its preferred food, is precisely drafted. Peale takes clear pleasure in depicting each foot, bristle and segment in tiny strokes. “Walking, bending, and inching up branches, Peale’s caterpillars are a tour de force of observational art,” Tom Baione, director of the museum’s research library, writes in the introduction to the section.

We may marvel at the sheer biological persistence of the 17-year locust, but consider: Titian Peale’s lost illustrations are finally seeing the light of day after a metamorphosis lasting nearly 200 years.

Comments are currently closed.