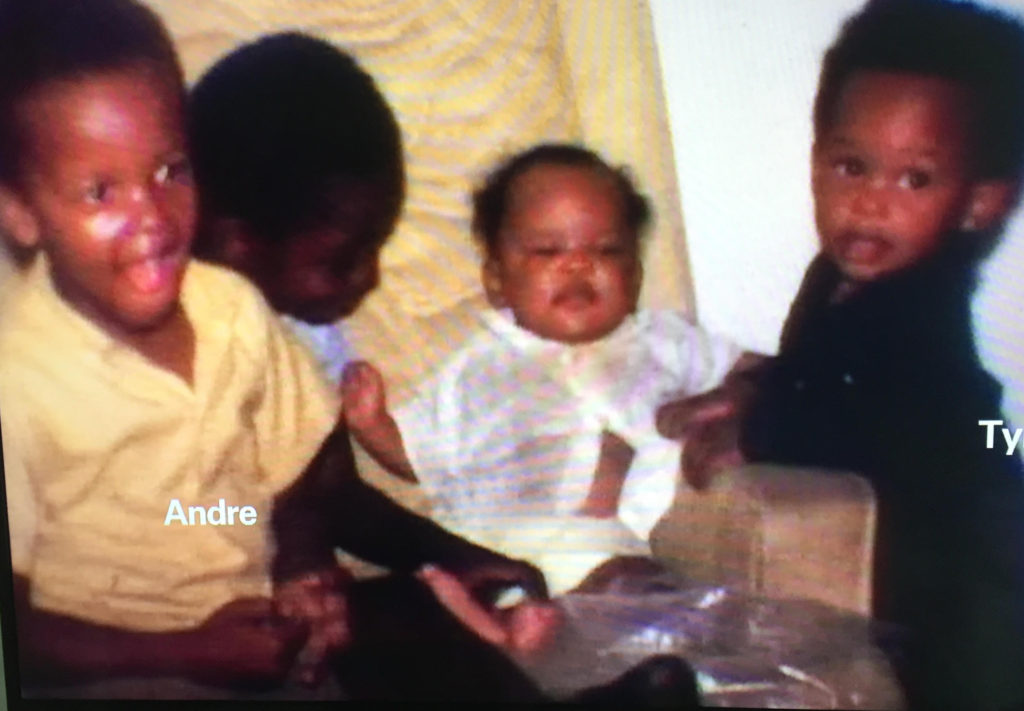

Thanks moms; thanks pops

Andre Young, aka Dr. Dre, and his brother Tyree, far right

The The Defiant Ones on HBO is a stirring documentary that made the hair on my arms stand up, exactly the way Dr. Dre got “goosechills” on camera as he remixed a favorite track from the past. The show humanizes this billionaire rapper in a way I haven’t seen since I spotted the snapshot of Nas when he was seven on the cover of Illmatic. That moment in the documentary, with Dre in thrall to a song from his past and the hair prickling on his arms, reveals the endearing nerd, the Dennis Wilson-obsessive, inside Dre—and, even moreso, within his business partner, Jimmy Iovine. An inner nerd drove each of them to the success they enjoy. Iovine’s incessant, fanatical, round-the-clock pursuit of production excellence resulted in a string of incredible career breaks as the skinny brilliant studio rat adjusting the mixer for John Lennon, Foghat, Bruce Springsteen, and Patti Smith, all of that just a launching pad for the success that followed. He and Dre both had the drive of Miles Teller’s character in Whiplash: a kind of zombie apprenticeship to an insatiable talent.

My first taste of Dre was his work with Snoop Dogg on Doggystyle. That mashup of funk and hiphop into a nasty celebration of gangster pleasures reminded me immediately of my forgotten delights in Johnny Guitar Watson back in the 70s. In both cases, funk and G funk, it was fun transgression, the way rock had once been a slightly forbidden pleasure. You knew it was just wrong, as it made you grin. Tipper Gore aside—remember her campaign against all of the foul language?–if you’re rapping, you can pretty much get away with anything. All is permitted, and so we’re free to enjoy all that badness vicariously, a musical day off from your own well-behaved boogie life. Along with Nirvana, it felt like a cure for everything that had happened to music in the 80s other than the rest of the bands that emerged out of punk.

Hiphop had been keeping alive the worship of a certain kind of beat that had been the soul of rock and roll when it began and had gotten harder and harder to find in pop. With Dre’s work, the limbic brain woke up and started listening again to that sliding, continuous throb, like a boa constrictor. I’m creepin and I’m creepin and I’m creepin. Dre may be the man who turned the sub-woofer into the essential component of a stereo. He altered everyone’s expectations of how music ought to sound, with that subsonic rumble in your chest. Nothing else in the genre sounded that lush and three-dimensional and perfectly mixed. He combined the bass foundation with an unexpected combination of sounds to generate his trademark slow, steady flow: the high synth treble organ note like a muezzin calling Snoop to the mic on Nuthin’ But a G Thang, and the minimalist quality of all the instrumentation, just barely enough to establish the sound, pulling you along into their words. Yet behind and beneath it all is the constant minor key of all the melodic elements, the sobering backdrop of sadness. Still Dre, nearly a decade later, starts with that little cluster of notes, again a minor key chord that could have been plucked from a ukulele or a harp’s tiniest strings, not exactly the sort of sounds one would expect from rap. With the alternation of those two chords, the sorrow of life steps into the foreground, as prominent as the rapper’s voices, saturating their boasts with a haunting apprehension of loss. That’s Dre’s shy intelligence: he and Snoop act like the baddest asses alive but it’s against an orchestration that mourns for the world around them as they brag about surviving it. He gives you the whole picture of what they were representing, even though they weren’t living the street life. What else is there to that track but those two voices, the quiet drums, a bass line, and that little sequence of notes like a hornet buzzing in and out of earshot? Only Spoon can leverage so much out of such a restrained matrix of sounds.

Snoop brought his slinky, louche aura of ganja and gin into the enterprise and somehow the partnership generated Doggystyle, with a sound that felt totally unprecedented when I first heard it. Much of it was just an act, a representation of what they saw around them. Decency is always Dre’s default setting: the only drive-by shooting on his rap sheet led to an arrest for firing paint balls at bus stops. And even behind Snoop’s criminal persona, his good-heartedness peeks through in his cameo turn on Gang Starr’s In This Life, where you can hear him speak sotto voce about his struggles without any of the posturing. As Dre’s business annexed more and more of the street, along with the guns these new players carried, Dre stuck with it, seeing the conflicts through to their bloody conclusion, and then he pulled back toward his roots.

What I love most about this documentary are the early little glimpses of the family life you get in the upbringing of both Dre and Iovine. Behind the G (as in genius) you’ll discover the decency of a middle-class parent devoted to raising a good kid, not a star. Jimmy Iovine’s father was his best friend. The kid couldn’t finish college, couldn’t hold down a job, but he finally connected with The Record Plant and the owner took him on as his protégé, though “puppet” would be a better description. Iovine says that Roy Cicala turned him into an extension of Cicala’s brain. “He would teach you by working through you,” Iovine says. He sat at the console and simply did whatever Cicalo dictated, turning all of the other man’s production intelligence into Iovine’s muscle memory. One day the studio calls Iovine’s family—an Italian Catholic clan in Brooklyn, sitting down for the holiday dinner on an Easter Sunday, no less—and the studio said they needed him to come down and work. His parents let him go, despite the fact that the whole extended family would be there for the meal. They cared that much about his hopes and dreams. And he was eager to go, which was the test he passed: his reward was that John Lennon awaited him in the studio. From there he went on to one success after another. Yet after being fired by Foghat, he came into the studio and went into all-or-nothing mode, working on his own, experimenting, tinkering, inventing projects for himself after hours, studying, studying, studying, slaving through every waking moment, all on his own with no reward for any of it—and Patti Smith was watching it all from the hallways. She’d never seen anything like it. Secretly, she picked him to produce her next record, without anyone at the studio knowing what the two of them were doing, after hours, on their own, sub rosa. Because the Night emerged because Iovine had the nerve to ask Springsteen to give it to Smith. After that hit, people recognized her on the streets of New York. Everything else he accomplished came from the same obsessive, round-the-clock work ethic, and it gave him a confidence in his own judgment about what to promote.

When Dre’s mother is on screen, you realize that he grew up in the same kind of sheltering, nurturing home. She cared about him more than anything in her life. He talks about how he went into a club in his teens and, for the first time, heard a DJ scratching, and that single moment turned him into a different person: “It fucked me up.” He became totally obsessed with DJ-ing. So his observant mother bought him a mixer. He retreated to his bedroom and spent hours, days, mixing, and she couldn’t have been happier. “If you can hear them, you know where they’re at,” she says. Practice, practice, practice, and more practice. “Whenever I was home, I was practicing,” Dre says. “My mother was really happy about it.“ As she puts it: “All day I could hear the music blasting, and he asleep with the headphones on. I just took them off. I didn’t know how to turn anything off.” Then Dre’s own turning point came at Eve After Dark, a teen club in L.A. Alonso Williams remembers when Dre somehow took over the turntables and combined “Mr Postman”, a throwback to the Sixties, with a newly released “Jive Rhythm Tracks 122”. He wasn’t even working for the club, had just talked his way through the door, and then somehow talked his way to the DJ station behind the turntables. The video in the episode shows him wearing a purple silk outfit that made him look like a disco surgeon—and when he synchronizes those two songs, the whole club quits moving. All the dancers and the owner just stop and listen. It was his first time behind the turntables anywhere outside his bedroom. As Williams says, “People were still groovin’ but they were groovin’ confused.” The innocence and pure fun of the whole scene at that point comes through as a revelation: back then, hiphop was joyful and playful, nothing more than a new way to deliver the beat. (Lately, Chance the Rapper has brought some of that innocence back into the game.)

The most significant moment, for me, in all of this happens after the club shut down. Dre’s mother arrived to pick up her boy and take him home.

A few nights ago, Ice Cube was a guest on Fallon and, unrelated to the HBO documentary, he talked about his own childhood. His father and mother had always been supportive of his work, but when N.W.A. became huge, his mother would quietly come to him and ask him if he couldn’t try to tone down the lyrics just a little. “She was sweatin’ me. I guess she was getting’ sweated by her church friends. Mom, we’re NWA! They were always supportive of what I was doing, as long as I wasn’t gang bangin’.” He wasn’t going to change anything, of course, but in a way she was bringing him back to his inner home. None of these guys have forgotten the universal, conventional values that made it possible for them to become the people they became. Like Mos Def’s Umi Says, this HBO show, along with everything else it represents, offers a shout out to the moms and pops. They deserve it.

Comments are currently closed.