Picasso’s moment of clarity

Marie Therese Walter and Maya

The desires of the heart are as crooked as corkscrews.

—-W.H. Auden

1

When I was visiting the L.A. County Museum of Art a year ago, I came across the final print from Picasso’s Vollard Suite in Fantasies and Fairy Tales, a small, beautifully curated selection of graphic work by various artists from around the early 20th century. It immediately changed my emotional response to Picasso as a visual artist. It struck me as fine in a way so much of his work isn’t—there was a subservient care for the image itself that seems largely absent from so much of Picasso’s work. Usually, he forces his images to work, creating an image that feels kinetic and improvisational, without many pains taken for any other quality. I’d seen reproductions of the print, but never before actually noticed the self-effacing craftsmanship that went into the dreamy light that illuminates his figures in the Vollard print. By establishing that diffuse stage lighting, from below the players, with the light source hidden off to the left at ground level, he bathes the  last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order Picasso Prints: The Vollard Suite, and to keep returning to it through the rest of 2019, off and on studying what Picasso had done in it, leading me to conclude that these prints may have been his most original and personal (those two adjectives are mutually dependent) contribution to Western art. Much of the suite may not rank as his finest work on technical grounds, nor his most beautiful, nor his best on many different levels, but they are what I would save of everything he did, if I had to pick one achievement of his to take to a desert isle. I suspect no one else in the history of art has done what Picasso did here: it’s almost as if he is undercutting and cancelling everything he’s accomplishing as he achieves it, fusing the act of creation and destruction and creating images of great beauty in the process. All of this was in the service of the brief stirrings of a moral self-doubt he managed to suppress in himself once he’d painted Guernica, which served as a sort of footnote to this series of prints.

last moments before the Minotaur’s violent death with an inviting, tranquil peace (if you interpret the print as his version of the myth of Theseus). I wasn’t familiar with this narrative at the time, but simply responded to how brilliantly Picasso achieved something here that seemed visually distinct from his most familiar and famous work. The scene was intimate, intensely personal, full of emotion and tenderness, conveyed with masterful, loving craftsmanship. These formal qualities of the image and the print, a combination of aquatint, drypoint and engraving, left me wanting to know more. That one glimpse of the Minotaur prompted me, once I got back home, to order Picasso Prints: The Vollard Suite, and to keep returning to it through the rest of 2019, off and on studying what Picasso had done in it, leading me to conclude that these prints may have been his most original and personal (those two adjectives are mutually dependent) contribution to Western art. Much of the suite may not rank as his finest work on technical grounds, nor his most beautiful, nor his best on many different levels, but they are what I would save of everything he did, if I had to pick one achievement of his to take to a desert isle. I suspect no one else in the history of art has done what Picasso did here: it’s almost as if he is undercutting and cancelling everything he’s accomplishing as he achieves it, fusing the act of creation and destruction and creating images of great beauty in the process. All of this was in the service of the brief stirrings of a moral self-doubt he managed to suppress in himself once he’d painted Guernica, which served as a sort of footnote to this series of prints.

2

The Vollard Suite isn’t what I like most from Picasso, which have to be his portraits of various lovers, wives and children, and the often beautifully lit paintings of massive, neoclassical women. Some of his abstracted figures are powerful, but most of his work as he was inventing Cubism with Braque seems monotonous in retrospect. What makes the Vollard Suite unique is also what makes it ahistorical, though the series is clearly of its time: modern in the sense of being thoroughly anchored in surrealism, with a glance or two back toward Cubism. It’s also postmodern in its many self-referential subversions of its own beauty. Yet it’s mostly neoclassical in spirit, tone and ambition—to an almost reactionary degree—though his masterful lines morph into something rich and strange before he’s finished. These prints hint at a yearning for innocence through the intensity of their plea for lucidity, for an impossible way out of the blind passions that invest them with life. They yearn for goodness and wisdom, and even offer the glimpse of an ambiguous spiritual harbor, which remains just out of reach.

Almost none of these characteristics can be found elsewhere in Picasso’s work, and his public persona never hinted at any trace of brooding in his personality. In his life, he comes across as the picture of health and strength, a happy, self-absorbed, sunny Mediterranean hedonist. Mostly, throughout his career, Picasso revels in the ease of his talent, his incredible facility with line, his priapic energy and inventiveness, his cleverness in seeing and seizing an emerging market for certain kinds of work, and his ability to promote himself as a sort of cross between sexual conqueror and family man, violator of taboos, both moral and artistic, while also coming across as a paterfamilias who loved letting kids run rampant in his chaotic studio. The Vollard Suite depicts some aspects of this multiple persona. It showcases Picasso’s incredible gifts as a draftsman, his Jedi-like ability to create a world of beauty with a few gestures. But ultimately the suite builds to a new self-awareness, a doubt that verges on despair. The work as a whole is, among everything else, a self-portrait, and what he sees in the mirror of his art is beautiful and monstrous, and this self-awareness only intensifies the work’s power and beauty. That’s the paradox that locks him inside this maze of images as he creates it. It’s Picasso’s most inexhaustible work, partly because it asks what his art is and shows the toll it takes. He asks whether it amounts to anything but a pointless, meaningless will to power, and he comes up empty. His dread is that all of his art, and maybe all art, amounts to nothing more than self-aggrandizing grotesquerie or beauty. This is what drives the work toward its enigmatic, penultimate print, Minotauromachy and its sister, Guernica.

Normally, I wouldn’t be drawn to any of this. The Vollard Suite is full of meaning, and visual art isn’t doing what it’s best equipped to do when it’s generating meaning. Painting does its greatest work immediately and perceptually, sensorily, bypassing ideas and concepts. This series of prints is full of ideas. Picasso wants you to see how, as he continues making these prints throughout the 1930s, he is attempting to stand back from his own work to see the spiritual price he pays for the ability to make it.

3

In his famous painting of Raphael, Ingres gives all the power to the Renaissance painter’s mistress, who gazes at the viewer almost with a wink of pride and pleasure. She rules the studio. She has brought the  famous Renaissance painter to heel through the image he is painting of her: she enraptures Raphael by proxy. This is a painting about her, not Raphael, and he has submitted to her beauty far more thoroughly than she has submitted to his gaze. She subjugates him by doing nothing but being there in his presence. She remains serenely inviolate, on top. He isn’t looking at her. He is more interested in looking at his painting of her than of having sex with his readily available consort. Vasari’s legend was that Raphael killed himself with lust: depleted and exhausted from his erotic devotions, he died young. Ingres depicts him as less interested in his love than in how she could enable him to paint. Either way, his passion wore him out, dying at the age of 37.

famous Renaissance painter to heel through the image he is painting of her: she enraptures Raphael by proxy. This is a painting about her, not Raphael, and he has submitted to her beauty far more thoroughly than she has submitted to his gaze. She subjugates him by doing nothing but being there in his presence. She remains serenely inviolate, on top. He isn’t looking at her. He is more interested in looking at his painting of her than of having sex with his readily available consort. Vasari’s legend was that Raphael killed himself with lust: depleted and exhausted from his erotic devotions, he died young. Ingres depicts him as less interested in his love than in how she could enable him to paint. Either way, his passion wore him out, dying at the age of 37.

The need for sex as a catalyst for art is the central subject of The Vollard Suite. Many images in the suite are about the centrality of the human gaze in sex and visual art. In a similar way, the Ingres painting shows how the craving to see what one can create can govern an individual, regardless of the consequences. Picasso was obsessed with Ingres, and that neoclassicist’s La Fornarina serves as a key to The Vollard Suite, as Stephen Coppel notes in his commentary. In that painting, La Fornarina is as much in control of everything around her as are the women in Fragonard’s The Progress of Love at The Frick. Women pick men, not the other way around. Proust’s description of how Odette seduces Charles Swann in the first volume of his great novel shows how she gradually and patiently addicts him to her cleverness over time, having chosen him long before he mistakenly thinks he is choosing this her. She transforms his Platonic interest in her—a woman who isn’t his type and doesn’t strike him as terribly attractive—into a sexual obsession that destroys his authenticity as a person and prevents him from finding himself as an art critic. One can read the same scenario into the Ingres painting, except the outcome is the reverse: Raphael becomes himself, achieves his maturity as an artist because of his mistress—she doesn’t destroy him, she creates him. Picasso had to have been thinking of this painting by Ingres throughout his creation of The Vollard Suite. It’s a great blueprint for what’s happening throughout the suite: though in the foreground you can see Picasso’s sense of self-doubt and skepticism over his own erotic exploitation of women for his art, he’s clear-eyed enough to recognize that what he seeks in his lovers is actually beyond his ability to appropriate it. (As it always is in Proust.) Marie-Therese represents more than sex here. She is Picasso’s La Fornarina, but also his Beatrice, even though she can’t light the way for him to escape the claustrophobia of his own compulsions.

At the basest level, what women represent in The Vollard Suite ought to be catnip to Donald Kuspit, who leans heavily on Freudian in his criticism. The Vollard Suite gets to the heart of his insistence that art be about embodiment, acceptance of the body and its drives. His critique of DuChamp is that the cerebral theorist loathed his body and its needs and thus hated art. Kuspit doesn’t address how much Picasso’s example could serve as a lesson to confirm his own insistence on how art needs to embrace bodily life. Picasso ought to be the artistic hero for a Freudian: everything for Picasso originates in sex. In an excoriating essay on Picasso, published last April, Donald Kuspit brilliantly skewers Picasso as a sort of vampire, bleeding the life out of everything of quality in the past—taking the Old Masters and pushing them through the meat grinder of his fragmentary art, debasing what was of the greatest value in the Western tradition and subjecting it to his post-modern mockery. It’s all classically Oedipal, in his view, killing his artistic fathers, one by one. It’s a deliciously contrarian critique of the greatest of all the celebrity artists, and it’s full of truth. Kuspit writes: “He took on Courbet, Delacroix, Goya, Manet, Delacroix, Rembrandt, and perhaps most famously Velazquez’s Las Meninas. They were his antagonists, and he boldly attacked them with violent rage, triumphing over them by destroying their works.” He continues: “His great art, born of his compulsion to work and fuck, is fueled by great self-doubt, informed by cynical recognition that greater art existed—and, more broadly, that art had already happened, and in a sense was over.” Later in the essay, Picasso expands to cosmic proportions, becoming for Kuspit not only a sort of Gnostic demiurge but also a Catholic Grand Inquisitor. To sum it up, he’s primordially bad, as man and artist, even though he’s the perfect exemplification of Freud’s psychology. He’s acting out Freud’s whole psychosexual drama. It’s unclear why a strictly Freudian critic would find anything missing here.

Regardless, one passage from this essay alone demonstrates Kuspit’s brilliance, summarizing the predicament for an artist now, where the only real answer to an infinite multiplicity of opportunities is to focus on individuation. The challenge is to create work governed by genuine love, excavated in solitude through years of discipline (though I don’t think Kuspit would use the world love, since Freud has no room for it in his biology):

Picasso epitomizes the paradoxical situation of modern art: on the one hand, a sense of infinite possibilities, of optimistic openness—a sense that “anything goes”; on the other hand, a sense of déjà vu, the depressing realization that everything has been done before, that all a modern artist can do is exploit and riff off some art of the past, improvise his or her individuality out of its remains. In other words, modern art is oddly regressive however progressive it claims to be, for it is grounded in pre-modern art. Neo-classical Picasso cursorily copies it, Cubist Picasso nihilistically tears it apart, Surrealist Picasso perversely distorts it, but without it there is no “modern” Picasso. His art is a kind of malicious, sarcastic commentary on traditional art based on an encyclopedic knowledge of it. He consumed it with a defensive rapidity; destroying it he became creative, ingeniously raping it he became a cynical genius.

It sums up visual art’s predicament. Yet I keep coming back to what’s implicit in the passionate craftsmanship of The Vollard Suite and how it almost leads Picasso toward a way to transcend himself and his situation. What enables Picasso to do work of genuine quality in these prints is that he is bound by the commission, the job at hand. He is serving someone and something other than himself. This submission to external requirements finds expression in the great care he invests in his marks, the exquisite neoclassical line of the early and middle prints, then the frenetic, almost psychotic intensity of the Surrealist imagery. The quality of attention to the image, the work itself, is incredible and it’s that intensity of attention that opens the door to what make this series of prints the work where Picasso most fully realizes himself as an individual artist. Yet despite the quality of his craft, all along he knows the work is ending up as little more than a meditation about his transformation of a particular kind of irresponsible erotic love into art. He is brutally honest about himself in these prints and his self-doubt here gives the work an uncompromising humility, qualities completely alien to the rest of his work.

The Vollard Suite shows how this great, modernist revolutionary found his most heartfelt home as an artist in Neoclassicism of all things: it was his bulwark (no pun intended) against the chaos of his own impulses and appetites. (As it was for many artists after the horror of the First World War.) It’s there in some of the earliest work and resurfaces again and again over the decades. The figures in his Blue and Rose Periods draw much of their evocative beauty from their masterful fidelity to the outline of natural human form, and a draftsmanship that often edged toward caricature was confident and nuanced and full of feeling. Kuspit sees only post-modern destruction of previous art in Picasso’s assimilation of someone like Ingres, but here Ingres is someone he imitates out of genuine respect, love and admiration. Here, the only artist he intends to destroy is himself.

4

In 2012 British Museum Press published Picasso Prints, The Vollard Suite edited by Stephen Coppel. It offers a way to walk through the entire suite, in rough chronological order, with some slight shuffling to present the prints in a sequence of “movements” as it were: the earliest collection of prints leading to the central themes: Battle of Love (euphemism for rape), Rembrandt, The Sculptor’s Studio, The Minotaur, and The Blind Minotaur (followed by the postscript of the final three tribute portraits of Ambroise Vollard, the art dealer who commissioned the work.

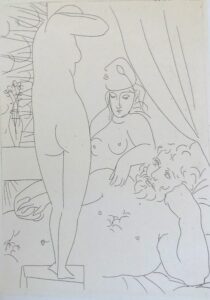

The images begin with female nudes that have the simplicity of forms on Attic pottery, images of repose and tranquillity. They are beautiful in their minimal, almost cartoonish line, like the work of a precocious child. They point back to the Blue and Rose periods. The line drawings in the suite, in general, echo not only pencil portraits Ingres did, but also the masterful drawings Matisse was doing at roughly the same time. The proportions and monumentality of these women sometimes bring to mind Maillol or Henry Moore or even Braque’s Canephora. Among these simple outlines of female nudes, he interjects figures more densely inscribed and then suddenly, in Man Uncovering a Woman, a menacing male intruder, looming over a sleeping woman. In a striking way, the interloper prefigures Francis Bacon’s taut, twisted males, decades later. The man breaks into the scene, frozen in the pose of voyeur, threatening to do more than just loom. A few etchings later, the ninth depicts a reworking of the same scene, entitled Rape. The suite shuttles back and forth between alternate visions of this world where people gaze at each other or at figures turned into objects. The gazing male is creative or dangerous, while the female serves as audience, victim, idol, or passive inspiration—completely objectified. Two prints later, with lines that seem to be the track of a palsied hand, he sketches three women and a flute-player in a swirling composition, like a quick notebook study for one of William Blake’s whirlwinds. The viewer begins to ask, where is this going?

Maillol or Henry Moore or even Braque’s Canephora. Among these simple outlines of female nudes, he interjects figures more densely inscribed and then suddenly, in Man Uncovering a Woman, a menacing male intruder, looming over a sleeping woman. In a striking way, the interloper prefigures Francis Bacon’s taut, twisted males, decades later. The man breaks into the scene, frozen in the pose of voyeur, threatening to do more than just loom. A few etchings later, the ninth depicts a reworking of the same scene, entitled Rape. The suite shuttles back and forth between alternate visions of this world where people gaze at each other or at figures turned into objects. The gazing male is creative or dangerous, while the female serves as audience, victim, idol, or passive inspiration—completely objectified. Two prints later, with lines that seem to be the track of a palsied hand, he sketches three women and a flute-player in a swirling composition, like a quick notebook study for one of William Blake’s whirlwinds. The viewer begins to ask, where is this going?

What began as a yearning, static, neo-classical homage to the human figure has morphed into something unpredictable, unstable, hallucinatory, drawing from multiple influences and periods of art history. In the process, Picasso attempts to face and depict the moral and spiritual ambiguity of what he’s doing in his life and art.

In the Picasso Prints sorting, the twelfth and thirteenth etchings are two of the most fascinating and resonant, hinting at the phantasmagoria to come. The twelfth offers a simple, amazingly individualized line drawing of a young man, arms open as if for a hug, as he gazes reflectively at the figure of an old man smoking a pipe, drawn in intricate, almost psychedelic curlicues, rows and rows of them, his beard a dense nest of dreadlocks. The title is Two Catalan Drinkers, but the image could also be interpreted as the moment when a young artist slowly withdraws his hands after having made the last modification to a sculpture of an aged man assembled out of what could have been twisted shavings from a metal lathe. Across from him, Picasso opposes the relaxed, confident and life-like young sculptor gazing at this solidified phantom, maybe a premonition of the younger man’s future self, half a century hence, a beret still atop his head. It appears to be a confrontation between an actual person facing the materialization of his inner apprehensions. It’s a realization of the governing dynamic throughout the series: the act of looking and of being observed, the merging of subject and object, and the act of creating what is observed. In this case the creator and creation, subject and object, could easily be identical.

In the Picasso Prints sorting, the twelfth and thirteenth etchings are two of the most fascinating and resonant, hinting at the phantasmagoria to come. The twelfth offers a simple, amazingly individualized line drawing of a young man, arms open as if for a hug, as he gazes reflectively at the figure of an old man smoking a pipe, drawn in intricate, almost psychedelic curlicues, rows and rows of them, his beard a dense nest of dreadlocks. The title is Two Catalan Drinkers, but the image could also be interpreted as the moment when a young artist slowly withdraws his hands after having made the last modification to a sculpture of an aged man assembled out of what could have been twisted shavings from a metal lathe. Across from him, Picasso opposes the relaxed, confident and life-like young sculptor gazing at this solidified phantom, maybe a premonition of the younger man’s future self, half a century hence, a beret still atop his head. It appears to be a confrontation between an actual person facing the materialization of his inner apprehensions. It’s a realization of the governing dynamic throughout the series: the act of looking and of being observed, the merging of subject and object, and the act of creating what is observed. In this case the creator and creation, subject and object, could easily be identical.

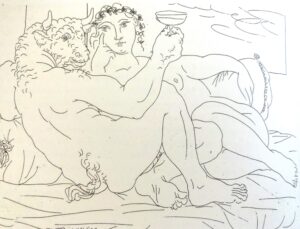

The closed system of this creativity, the way it shuts out the larger world, the way in which everything in the series seems to become a projection of the mind and desires of its creator—as if all of Picasso’s art is solipsistic self-portraiture—becomes a trap, a labyrinth. In the last of these prints, the richest of the series, Picasso asks how to escape this trap. Everything finds its apotheosis in the figure of the Minotaur, its violence, appetite, imprisonment, and ultimately its doom. The way the old man is drawn, the almost compulsive density of its lines, recurs in the way Picasso draws the winged bull in the next etching—a precursor of the Minotaur, as well as his rendering of Rembrandt further on. (Rembrandt is presented almost as a harmless besotted voyeur—confirming Donald Kuspit’s thesis about Picasso’s destructive mockery of the past, in this case turning Rembrandt into a clown.) In a similar way, the winged, griffin-like bull in the thirteenth print stands in powerless obedience on a freak show stage for an audience of four young women, awed, apprehensive, but also amused. This hybrid of a Minotaur has become an entertainment, a carnival exhibit, a new exotic car on a showroom floor. Like Rembrandt, who will appear a few prints later, he has dizzy little spirals for eyes. At this point, he is the captured object for the female gaze, a marvel, an attraction, part woman himself, part beast, part bird. He is the vassal, the man in love. He is their amusement, their prize. We aren’t even a fifth of the way into The Vollard Suite and already Picasso has drawn the viewer into his Surrealist alternate reality where the marauding Minotaur becomes a feeble, lost captive in his own predatory arena. (An arena where the women end up safely beyond his power.)

The closed system of this creativity, the way it shuts out the larger world, the way in which everything in the series seems to become a projection of the mind and desires of its creator—as if all of Picasso’s art is solipsistic self-portraiture—becomes a trap, a labyrinth. In the last of these prints, the richest of the series, Picasso asks how to escape this trap. Everything finds its apotheosis in the figure of the Minotaur, its violence, appetite, imprisonment, and ultimately its doom. The way the old man is drawn, the almost compulsive density of its lines, recurs in the way Picasso draws the winged bull in the next etching—a precursor of the Minotaur, as well as his rendering of Rembrandt further on. (Rembrandt is presented almost as a harmless besotted voyeur—confirming Donald Kuspit’s thesis about Picasso’s destructive mockery of the past, in this case turning Rembrandt into a clown.) In a similar way, the winged, griffin-like bull in the thirteenth print stands in powerless obedience on a freak show stage for an audience of four young women, awed, apprehensive, but also amused. This hybrid of a Minotaur has become an entertainment, a carnival exhibit, a new exotic car on a showroom floor. Like Rembrandt, who will appear a few prints later, he has dizzy little spirals for eyes. At this point, he is the captured object for the female gaze, a marvel, an attraction, part woman himself, part beast, part bird. He is the vassal, the man in love. He is their amusement, their prize. We aren’t even a fifth of the way into The Vollard Suite and already Picasso has drawn the viewer into his Surrealist alternate reality where the marauding Minotaur becomes a feeble, lost captive in his own predatory arena. (An arena where the women end up safely beyond his power.)

5

The experience of refining one’s skill as a painter is one of increasing submission. This is a truth Picasso exemplifies only in his best work. It’s a paradox of mastery in that it puts the painter utterly at the mercy of what has to be done, what the painting requires, not what the painter wants. The task is the master and the greatest painter is merely equal to its demands. On rare occasions the job’s requirements and the painter’s desires perfectly merge and the ability to do what’s required feels like power. In Picasso’s case, more often than not, he gives the impression of being determined to impose his desires on his medium and force the emergences of an equally domineering image that demands the viewer’s assent, over which Picasso exerts arbitrary control, in service to nothing but his impulses. It isn’t hard to take that sentence and replace some nouns and have a good description of his relationship with women: women went from goddess to doormat after a certain period of time. Guernica has much of this quality, and its dismayed reception when it was unveiled in the town of Guernica reveals how much Picasso disdained those who accepted his status as a major artist and commissioned his work. Yet his neoclassical figures are an exception, along with much of his early work, and in some of the portraits of his wives and lovers, where he submits to the requirements of craft and precision and is clearly serving something other his desire to paint. This is what he does in The Vollard Suite.

Anyone who leafs through the Coppel publication will be struck by how, occasionally, it shows Picasso’s bridling at the requirement of his commission. Some of the prints are images he might have destroyed if he hadn’t had to fill out the collection to deliver the agreed-upon one hundred prints. Heads and Figures Entangled is a sheet of studies pulled from a cracked plate. Cracked or whole, he didn’t care and  included it as as the 18th print. Female Bullfighter III appears to have so frustrated the artist that he scratched three thick vertical lines through it to cancel it. No matter. In it went. The hubris of his disrespect for the set’s integrity reveals his ambivalence about himself and his role as celebrity painter. It’s as if he wants to show himself up as a fraud, knowing that his reputation makes him invulnerable. The quality of what he does hardly matters now. Picasso claimed that everything he did was the visual equivalent of an autobiographical notebook and thus worthy of interest. Even his worst work should be hung or published beside his best. In this case, the inclusion of the inferior or flawed or incomplete work actually serves to highlight the quality of the rest. A canceled and awkward sketch appears side-by-side with a vertiginous and densely drawn dream of a sleeping or unconscious woman sandwiched between a marauding bull and a frantic horse—one of the most powerful and carefully crafted dreams in the entire collection. If nothing else, the inferior work on the adjacent page amplifies this one’s magnificence.

included it as as the 18th print. Female Bullfighter III appears to have so frustrated the artist that he scratched three thick vertical lines through it to cancel it. No matter. In it went. The hubris of his disrespect for the set’s integrity reveals his ambivalence about himself and his role as celebrity painter. It’s as if he wants to show himself up as a fraud, knowing that his reputation makes him invulnerable. The quality of what he does hardly matters now. Picasso claimed that everything he did was the visual equivalent of an autobiographical notebook and thus worthy of interest. Even his worst work should be hung or published beside his best. In this case, the inclusion of the inferior or flawed or incomplete work actually serves to highlight the quality of the rest. A canceled and awkward sketch appears side-by-side with a vertiginous and densely drawn dream of a sleeping or unconscious woman sandwiched between a marauding bull and a frantic horse—one of the most powerful and carefully crafted dreams in the entire collection. If nothing else, the inferior work on the adjacent page amplifies this one’s magnificence.

One would rarely think of Picasso as personally or artistically careful as he is in drawings like this. The history of his erotic life shows how much he served his impulses, regardless of the consequences, going from one woman to the next as soon as his current relationship constrained him. A pregnancy was often the signal that it was time to move on. An early mistress, known as Madeleine, had an abortion, as a result of her affair with Picasso, but was soon abandoned. Another mistress he allegedly kidnapped: she escaped and then returned to him later, apparently won over by the audacity of his crime. When Olga Khokhlova, his wife at the time he was creating The Vollard Suite, became pregnant, his marriage began to dissolve, at which point he seduced and began his affair with Marie Therese—keeping her as his mistress. And, inevitably, his recurrent seven year itch destroyed his idyll with Marie Therese around the time she became pregnant by him—at which point Olga left him and refused to give him a divorce. It’s hard to think of his love life as anything but an epic catastrophe, in moral or simply logistical terms. Marie Therese, probably the most vulnerable of all his lovers, continued to raise their child, with Picasso’s assistance and continued devotion–years after they parted ways–and she committed suicide in the 1970s, but only after Picasso died. He continued to love her and care for her and his daughter even when he was living with his later wives.

All of this emotional waywardness has been obsessively documented, but The Vollard Suite offers evidence that these years almost exclusively devoted to Marie-Therese were qualitatively different from any other period of Picasso’s life. She awakened in him the stirrings of a moral consciousness and possibly a sense of spiritual yearning otherwise completely alien to his personality and character. She seemed to open a small window of spiritual opportunity for Picasso, which he recognized and then rejected. She was his moment of clarity, but he declined to act on it.

6

After the early images, the suite shifts gear briefly, just before the violence appears, moving into a shadowy, reverent chiaroscuro in a brief sequence of two prints that show a male figure in adoring attendance beside a sleeping woman. These two hint at the only real faith Picasso had: it was this recurring worship for one woman after another for as long as he could regard her as an idol, a goddess, someone whose beauty transformed all of his perceptions, renewing him and his appetite for life. In these two prints–a male observer, a boy slightly reminiscent of Picasso’s images of Pierrot, and a centaur reaching for a nude woman asleep in her chamber–he shows the tentative, dazzled spirit of someone who is entirely dependent on a woman’s beauty to find his bearings in the world.

someone whose beauty transformed all of his perceptions, renewing him and his appetite for life. In these two prints–a male observer, a boy slightly reminiscent of Picasso’s images of Pierrot, and a centaur reaching for a nude woman asleep in her chamber–he shows the tentative, dazzled spirit of someone who is entirely dependent on a woman’s beauty to find his bearings in the world.

For Picasso, being in love, and the sex it entailed, was his addiction and his only faith. He was observant enough to have already become familiar with both the creative and destructive sides of this quest. In these gentle, glowing images of worship he offers the viewer a moment to see the benevolent side of his passion. Then, immediately—in the sequence provided by Coppel’s book—he coldcocks you with one image of rape after another. The human figures look as if they are chiseled from stone, assembled out of granite shards, devoid of warmth, like the ghostly stone molds of people  who were fossilized in the eruption of Pompeii. The images are as stark and honest as anything Picasso ever created, and they are testimony not simply to the rough sex he may have favored, but to his deep ambivalence about himself and his life. This is where The Vollard Suite distinguishes itself from nearly everything else Picasso created: in the intense self-doubt that begins a third of the way into the suite and becomes more and more explicit as it moves toward its conclusion.

who were fossilized in the eruption of Pompeii. The images are as stark and honest as anything Picasso ever created, and they are testimony not simply to the rough sex he may have favored, but to his deep ambivalence about himself and his life. This is where The Vollard Suite distinguishes itself from nearly everything else Picasso created: in the intense self-doubt that begins a third of the way into the suite and becomes more and more explicit as it moves toward its conclusion.

His idiosyncratic drawings of a clownish Rembrandt follow this bleak glimpse of Picasso’s use of force to get what he wants—as if to suggest all he can see through the haze of his own erotic reverie is an old artist reduced to voyeuristic impotence, another glimpse of his own future. These projections of himself onto Rembrandt echo the paradox at the heart of The Vollard Suite—it shows a man helplessly aware of his own lostness clinging to the hope that the artwork this awareness generates might redeem him. Picasso has to keep losing his way in order find himself as an artist. This set of etchings and aquatints, and the labor he put into them over seven years, should be considered Picasso’s most original work, in that it’s doing something, in its recursiveness—the way in which it assert and cancels itself out at one and the same time—that few artists have ever felt the need to attempt. Picasso was self-aware, throughout this work, in an unsparing way, giving the suite what is virtually a unique place in Western art. (Picasso knew he was a pretender, a trickster, a predator. It isn’t hard to argue that Picasso merely slipstreamed behind Braque in the invention of Cubism, Braque being the artist who most wanted to become Cezanne. But the self-awareness in The Vollard Suite is moral. It’s as much about Picasso’s personal life as it is about his art.)

If you think of Melville’s essay on the whiteness of the whale, Picasso in these years is a bit like Ahab catching sight of the whale, finding absolute fulfillment of his purpose—creating art of multi-faceted complexity, realizing himself as an artist more fully than he would before or after. But as he does so, he sees that it’s about nothing but sex. As such, he’s an illustration of Freud’s theories, since Freud reduces human nature to an elaborite charade staged around sexual desire, or a sublimation of that urge into other activities. What else is Picasso demonstrating here? To recognize this, as Picasso was doing, had to have been equivalent to Nietzsche’s realization that the world was nothing but the will to power, blind, senseless, meaningless, with no purpose other than the amplification of itself. Sex and power (creative and personal) are virtually indistinguishable in these prints. Picasso recognizes the senselessness of the whole endeavor, the almost non-human compulsion at the heart of it—and yet he won’t stop, even as he recognizes that his work (along with the suggestions that maybe human motivation itself), is as destructive as it is creative.

His monumental paintings, Demoiselles d’Avignon and Guernica can be, and usually are, touted as historic achievements, pinnacles of invention, and the high points of Picasso’s seminal role in the modern era. But in comparison with the Vollard prints, they are relatively easy to interpret and seem like desperate bids for attention. By contrast, the prints are far more dense with craftsmanship and meaning. Guernica, in formal terms, feels like a falling away, a strident denunciation, a decline from the imaginative intensity and paradoxical ambiguities, the scrupulous craft and restraint that lift these prints into a dimension completely different from so much of Picasso’s work. Guernica is a spectacular indictment of technological warfare and human suffering. It wins its place in history by pimping, for political credit, the supple and elusive personal mythology that emerges from The Vollard Suite.

The lovely and appalling nightmare of the Vollard prints make Guernica’s political outrage look simplistically shrill, a collapse into a politically correct scream against an atrocity everyone already condemns. No one would disagree with it. It’s a sure win. It’s the safest image Picasso ever made, even if its sponsors disliked it. In Guernica, the accusation points outward at fascism, but The Vollard Suite aims its indictment at itself. The prints calls into question all human motivation and the nature of erotic love as the taproot of human creativity. Picasso brings you right up to the verge of showing you how easily it all implodes into a sort of cheesiness—from within.

Yet in all fairness he also shows the bliss. Midway, the suite becomes a long, graceful celebration of the happiness he must have enjoyed for several years with Marie Therese, making love and making art. In one print after another, Picasso displays his brilliant ability to create vivid images, full of life and personality with the most sparing use of line. In some cases, his talent for delineating the expressions in a face, the intelligence and emotion in a pair of eyes, with lines that must have taken less than a minute to lay down—it’s astonishing. He can create a uniquely individual face with a few marks of a stylus. I reacted to some of these prints the way David Hockney did when he gazed at Rembrandt’s quick sketch of a mother teaching her child to walk, almost magically accurate, in the way the Zen brevity of Asian ink drawings can convey the inner life of a bird or a plant with five or six strokes of ink on paper. Picasso’s line can turn a blank page into a world of erotic and artistic euphoria seemingly without effort—it’s the act of seeing reduced to the simplest terms. Though many see echoes of the Pygmalion myth in this large middle section devoted to happiness, I see it as just the opposite. Sculpture isn’t springing to life, but the other way around: Picasso’s project is to de-animate life into art, at the expense of life, like those human effigies from Pompeii.

Yet in all fairness he also shows the bliss. Midway, the suite becomes a long, graceful celebration of the happiness he must have enjoyed for several years with Marie Therese, making love and making art. In one print after another, Picasso displays his brilliant ability to create vivid images, full of life and personality with the most sparing use of line. In some cases, his talent for delineating the expressions in a face, the intelligence and emotion in a pair of eyes, with lines that must have taken less than a minute to lay down—it’s astonishing. He can create a uniquely individual face with a few marks of a stylus. I reacted to some of these prints the way David Hockney did when he gazed at Rembrandt’s quick sketch of a mother teaching her child to walk, almost magically accurate, in the way the Zen brevity of Asian ink drawings can convey the inner life of a bird or a plant with five or six strokes of ink on paper. Picasso’s line can turn a blank page into a world of erotic and artistic euphoria seemingly without effort—it’s the act of seeing reduced to the simplest terms. Though many see echoes of the Pygmalion myth in this large middle section devoted to happiness, I see it as just the opposite. Sculpture isn’t springing to life, but the other way around: Picasso’s project is to de-animate life into art, at the expense of life, like those human effigies from Pompeii.

These languorous figures dwell in the eye of a storm, with the series of rapes at the beginning and the  dense, troubled visions of the Minotaur that arrive afterward. He first appears as a clueless, hirsute fellow bacchante, turning the beauty of those studio-bedrooms into a sketchy free-for-all. The Minotaur’s appearance hints that something is odd and ominous at the heart of this bliss. Horse and bulls appear, ghosts of the bullfight, harmlessly attending the after-orgy, as it were, but in their roles they remind the viewer of violence, death, the animal origins of human life. They serve as a harbinger of the final prints where the tragic figure of the Minotaur appears.

dense, troubled visions of the Minotaur that arrive afterward. He first appears as a clueless, hirsute fellow bacchante, turning the beauty of those studio-bedrooms into a sketchy free-for-all. The Minotaur’s appearance hints that something is odd and ominous at the heart of this bliss. Horse and bulls appear, ghosts of the bullfight, harmlessly attending the after-orgy, as it were, but in their roles they remind the viewer of violence, death, the animal origins of human life. They serve as a harbinger of the final prints where the tragic figure of the Minotaur appears.

When Picasso shifts to his central subject, the Minotaur, the loveliness of the previous images degrades into reminders of the earlier rape scenes, the bullfight—the Minotaur is seen vanquished and dying with a weird audience of Marie Therese clones, looking down from their stadium seats on the wounded beast. In another print, a male figure hovers over a sleeping woman, but the dense nest of lines rendering his head looks like a storm cloud or some demonic materialization ready to occupy her head. This leads to the final set of prints, three studies for his image of the blinded Minotaur, and the print I saw at LACMA, in which he shows where his life and his work has led him, in 1935. As Coppel points out in the introduction to these last images, Marie Therese had become pregnant, Olga had left him, refusing the divorce, and he had been smitten with Dora Maar, knowing where his new infatuation will lead—away from the girl who had been his hope, his dream, and the center of his imaginative life for half a decade. Coppel quotes Picasso: “These were the worst days of my life.” Around all of this personal drama, Europe’s political divisions were coming to a boil, all of which imbued these final prints with foreboding and a sense of doom—but somehow Picasso found a way to make these darkest and most complex prints the most enchanted. This almost magical quality is what, for me, makes this moment, these final images, which represent a rapture of intense and careful craftsmanship, the pinnacle of Picasso’s career—the ecstasy has become misery, but the misery has become a supple, mysterious beauty through the alchemy of Picasso’s talent.

When Picasso shifts to his central subject, the Minotaur, the loveliness of the previous images degrades into reminders of the earlier rape scenes, the bullfight—the Minotaur is seen vanquished and dying with a weird audience of Marie Therese clones, looking down from their stadium seats on the wounded beast. In another print, a male figure hovers over a sleeping woman, but the dense nest of lines rendering his head looks like a storm cloud or some demonic materialization ready to occupy her head. This leads to the final set of prints, three studies for his image of the blinded Minotaur, and the print I saw at LACMA, in which he shows where his life and his work has led him, in 1935. As Coppel points out in the introduction to these last images, Marie Therese had become pregnant, Olga had left him, refusing the divorce, and he had been smitten with Dora Maar, knowing where his new infatuation will lead—away from the girl who had been his hope, his dream, and the center of his imaginative life for half a decade. Coppel quotes Picasso: “These were the worst days of my life.” Around all of this personal drama, Europe’s political divisions were coming to a boil, all of which imbued these final prints with foreboding and a sense of doom—but somehow Picasso found a way to make these darkest and most complex prints the most enchanted. This almost magical quality is what, for me, makes this moment, these final images, which represent a rapture of intense and careful craftsmanship, the pinnacle of Picasso’s career—the ecstasy has become misery, but the misery has become a supple, mysterious beauty through the alchemy of Picasso’s talent.

7

Minotauromachy is Picasso’s great work. Nothing else he did has its density and intricacy, both formally and in the way it assembles all of the personally-forged images he has been using throughout the suite into a tableau that shows the artist’s predicament and calls into question the nature of what he’s done. It’s impossible to believe that this didn’t originate as the final print of the commission, the one image toward which the entire narrative was building. And yet he held it back. He didn’t include it in the prints he delivered to Vollard and closed his story with the print I saw at LACMA, the blind Minotaur being led by Marie Therese, in her futile attempt to rescue him. Minotauromachy would have fit perfectly as the penultimate image before this doomed escape, but to place it in that position would have diminished the final print, which is the best of the existing set, and second only to Minotauromachy. It would have seemed visually anti-climactic to appear after this masterwork. To have reversed these two prints, so that the most accomplished appeared at the end, would have spoiled the story. They would be out of sequence.

To see how this is the case, it has to be clear that the Minotaur is about to be killed. In the myth, King Minos kept the monster imprisoned in a maze. Occasionally the king sent his navy to pillage Athens, until Athens offered a bribe: every nine years or so, the Athenian king would send Minos seven boys and seven girls to feed to the Minotaur in return for peace. Minos agreed. Prince Theseus volunteers to camouflage himself among the sacrificial youth in order to enter the labyrinth and kill the monster. With the help of Ariadne, on Crete, he uses her thread and the sword she gives him to kill the Minotaur and then find his way back out of the maze. As part of his bargain with her, he lets Ariadne escape from Crete along with him and the children, but he abandons her when she falls asleep on another island, en route back to Athens.

Picasso borrows from the myth to tell a slightly different story. In Minotauromachy, Theseus is on his way but there is still plenty of time to escape. You can see the sail of a boat barely visible on the ocean, at the horizon line between the horse’s tail and the Minotaur’s right leg. In Blind Minotaur Being Led by a Little Girl in the Night, Theseus, in sailor’s stripes, is stepping out of the boat, only a few feet away from his target. Picasso feels no need to show the Minotaur’s certain death: his fate is clear. Here, the stand-in for Ariadne is trying to help the Minotaur escape, not Theseus, even though it’s too late. So, I wonder if, instead of concluding his commission with the superior print and then need to leave out probably the loveliest, most lyrical image of all the ones he’d made, he reserved Minotauromachy as a stand-alone. It was completed only months after the last print in his narrative, and two years before the final three portraits of Vollard, which completed his commission. Along with Guernica, it is the crowning outcome of the years he put into this commission.

Picasso borrows from the myth to tell a slightly different story. In Minotauromachy, Theseus is on his way but there is still plenty of time to escape. You can see the sail of a boat barely visible on the ocean, at the horizon line between the horse’s tail and the Minotaur’s right leg. In Blind Minotaur Being Led by a Little Girl in the Night, Theseus, in sailor’s stripes, is stepping out of the boat, only a few feet away from his target. Picasso feels no need to show the Minotaur’s certain death: his fate is clear. Here, the stand-in for Ariadne is trying to help the Minotaur escape, not Theseus, even though it’s too late. So, I wonder if, instead of concluding his commission with the superior print and then need to leave out probably the loveliest, most lyrical image of all the ones he’d made, he reserved Minotauromachy as a stand-alone. It was completed only months after the last print in his narrative, and two years before the final three portraits of Vollard, which completed his commission. Along with Guernica, it is the crowning outcome of the years he put into this commission.

In Minotauromachy the density of lines testify to weeks of labor that went into realizing this print, in its final form, wonderfully described in detail by LACMA, with examples of the image in all of its seven developing stages. He ended up with a dramatic image that, in the context of everything that preceded it in The Vollard Suite, becomes a powerful and moving testimony to what is essentially Picasso’s anguish over himself and his art. Half-bull and half-man, he moves from the daylight toward a dark, cavernous space illuminated only by the candle that Marie Therese holds aloft. As he moves toward her, he leaves behind the familiar light and enters an enclosed darkness—what he has come to view as the arena of his creativity. In the distance, his executioner approaches, but there is more than enough time to flee.

Instead, the Minotaur holds out his hand, stiff-arming the light, not to extinguish the light but to defend himself from it. He’s being held at bay. Directly in front of him, between him and Marie Therese, a female toreador has merged with a horse, aiming her sword directly away from the Minotaur, toward Marie Therese. The half-naked woman is depicted as intensely desirable and vulnerable, amble breasts exposed, a step or two from being raped, not fending it off. In his own life, Dora Maar has come between Picasso, luring him with her beauty and talent, as an equal, keeping Picasso from reaching what the young girl promises him. What the child offers is clearly depicted: she can save him from his own nature. Her candle reveals the exit.

Above her, two women and a dove preside like Renaissance cherubs, emblems of love, peace and happiness, and behind Marie Therese a figure who clearly looks like Jesus, but has been referred to as “the philosopher” ascends a ladder, ascending out of this tableau. He could be any mendicant who has renounced the world seeking wisdom—prophet, sannyasin, saint, Socrates—though the loin cloth and the beard and hair are clearly meant as a nod to Christianity. It’s hard to find any other evidence that Picasso ever gave a second thought to spirituality. The fact that this anomaly appears here testifies to his sense of personal extremity. But this personification of wisdom isn’t abandoning the scene: he gazes back down with benevolence and compassion, a look echoed in the face of Marie Therese. He pauses on his climb, waiting to be followed. But the Minotaur is defending himself from the light that is opening up a view of his ascent away from his own despair. The look on the face of this figure in the loin cloth, and the expression on the face of Marie Therese, are hard-won achievements of Picasso’s draftsmanship; with the tiniest of marks, he could convey an entire and whole human personality, a world of emotion and compassion. (El Greco has this same astonishing ability with paint, as did the early Rembrandt.) In all fairness, it’s the skill of a great cartoonist, but in Picasso’s work it becomes something altogether different. Minotauromachy establishes the truth of Picasso’s life: he has the opportunity, with Marie Therese, to break the addictive cycle of his sequential love affairs and devote himself to this young woman whose goodness and joy illuminated his world for five years, but it would come at a cost he wasn’t willing to pay.

The final print in the narrative, the one Picasso actually included in the set, the one I saw at LACMA, depicts that price. In one sense it shows Picasso’s artistic dilemma: he needed to be passionately attended by a woman who captured his imagination in order to create his art. Marie Therese leads and  he follows. But in another sense, to remain with her, he had to blind himself. Looking and desiring and making art become fused in The Vollard Suite: to see and make love to a new beautiful woman was the only way he could motivate himself to make art as a recapitulation of that seeing and making. To break the cycle was essentially to choose blindness, to give up art. He’d decided that to blind himself would be death—as it will be shortly, in the final print, with Theseus stepping ashore. He has a choice: to become a good man, but an ordinary one, giving up his addiction to love, being led by the hand toward a better life. He could choose peace with Marie Therese as a path out of this desperate cycle of need. Or he could seize the latest naked woman, already wielding her sword to defend him, from her reclining seat on the back of the horse in Minotauromachy, so that he could move on to paint once again. He couldn’t resist Dora Maar and this is easily understood: she was a knockout, intelligent and gifted, not to mention a fresh sexual partner. He could have chosen to resist her, even if the cost was having no motivation to make art anymore (his art might actually have blossomed as a result of his choice in ways he couldn’t have imagined.) He could have chosen to be a man with personal integrity. What’s extraordinary about The Vollard Suite is that it makes clear that he knew he was nothing of the sort. He longed to find another way, but in the end didn’t have the courage or strength to resist himself.

he follows. But in another sense, to remain with her, he had to blind himself. Looking and desiring and making art become fused in The Vollard Suite: to see and make love to a new beautiful woman was the only way he could motivate himself to make art as a recapitulation of that seeing and making. To break the cycle was essentially to choose blindness, to give up art. He’d decided that to blind himself would be death—as it will be shortly, in the final print, with Theseus stepping ashore. He has a choice: to become a good man, but an ordinary one, giving up his addiction to love, being led by the hand toward a better life. He could choose peace with Marie Therese as a path out of this desperate cycle of need. Or he could seize the latest naked woman, already wielding her sword to defend him, from her reclining seat on the back of the horse in Minotauromachy, so that he could move on to paint once again. He couldn’t resist Dora Maar and this is easily understood: she was a knockout, intelligent and gifted, not to mention a fresh sexual partner. He could have chosen to resist her, even if the cost was having no motivation to make art anymore (his art might actually have blossomed as a result of his choice in ways he couldn’t have imagined.) He could have chosen to be a man with personal integrity. What’s extraordinary about The Vollard Suite is that it makes clear that he knew he was nothing of the sort. He longed to find another way, but in the end didn’t have the courage or strength to resist himself.

8

In a way The Vollard Suite confirms and then finds wanting the Freudian vision of human nature. Picasso ought to be the poster child for the argument that human nature is nothing but an elaboration of sexuality. In this suite and throughout his life, Picasso accepts his life, his art, his perceptions, his thinking, his hopes and dreams, are all governed by sex. Art is nothing but an extension of sexual desire: with Picasso it’s so overt and explicit that there’s no sublimation. He openly channels sex into paint, more or less. Wouldn’t Freud have celebrated this? If art, in Picasso, is nothing but “working and fucking” as Kuspit sees it, why is that a problem? Isn’t that all that art amounts to for Freud? There’s certainly a problem in Picasso’s dilemma, but hardly for a Freudian.

As the series progresses, Picasso’s vision turns from celebration into despair: he’s lost, and he knows it. Is this all there is? It’s an insight and a recoiling from the same insight that few in the 20th century—Camus maybe in the way he rejected theoretical extremes—ever reached. Picasso sees this new monistic vision of human nature as a trap, a prison. Much 20th century thought is conducted in similar reductionist prisons. Those who inaugurated the revolutions of the past century proposed equally simplistic theories of human life, reducing everything to one central principle.

In an essay published in 1978 in a Canadian journal of critical theory, Stan Spyros Draenos calls Freud an essentialist who replaces metaphysics with something that serves a similar role in its absence.

A single, radical insight founds the psychoanalytic perspective and remains its pole of orientation throughout . . . this single insight may be characterized as a redefinition of the essence of man. For psychoanalysis, that essence is desire . . . Reason becomes an instrument of psychical domination rather than the realization of a rationally-ordered harmony of the soul in Freud because it has lost its metaphysical sanction. Or, to put the matter another way, lacking metaphysical justification, reason loses all substantive content, all norm-giving force, and becomes merely the necessity-imposed regulative function of the ‘mental apparatus’—a means among means in the technique of living, while itself unable to determine the sense of living. Essentialism, the notion that a single principle or substance underlies all the manifestations of a particular entity, thereby making it be what it is, has its provenance in the heritage of metaphysics—a heritage which, cast adrift from its moorings . . . suffered shipwreck in the nineteenth century . . . Freud’s thought perpetuates essentialism in the aftermath of metaphysics by realizing the sense of essentialism in a radically altered setting.

What’s interesting about this examination of Freud’s attempt to replace metaphysics with biology is that it puts him in the same camp as the other two revolutionary, reductionist thinkers who became the architects for much of the intellectual and political upheaval of the past century: Marx and Nietzsche (who was the father of all the postmodernists who ascended in academia over the past fifty years). Freud turns human nature into a sexual phenomenon. Marx does the same with money: for him, human life is essentially economic. For Nietzsche power itself as the prime mover. Nietzsche is the most central thinker, because power is the goal for all of them, sexual power and economic power being just two versions of Nietzsche’s monism.

All of them radically simplify human experience, seeing everything people do through the lens of sex, money or power—or rather power in its various guises. All of these architects of modern life deny the nuance and complexity of human experience, along with the notion that there is a reality in life beyond what’s visible in this fleeting stage we occupy—they all reject that there is any governing essence of Goodness or Truth, or some other extra-temporal source of wisdom and morality, untainted by the inability of human beings to live in accord with it, that shapes human nature. In his lectures on his predecessor, Heidegger pointed out the central contradiction in Nietzsche, that his will to power was a metaphysical principle, and became the final metaphysical theory at the end of metaphysics, the most nihilistic in a long line of nihilistic models for truth (in Heidegger’s view). The same might be said of Freud and Marx. They replace metaphysics with forces that diminish human nature to the role of puppet rather than agent.

The irony is that they were obsessively rational themselves in their arguments to uproot reason as the essence of human nature, and they promote their theories as true, though the idea of truth itself is undermined by their theories. For them, truth is a fiction, a tool, rising up out of the will to power. If he were honest with himself, Freud would have said all of his insights were nothing but a sexually motivated invention and thus vulnerable to other views of human nature that might work more effectively to perpetuate sexual pleasure and the survival of the species. Marx the same: his theories were themselves the product of contingent economic and political ends in his own time, easily vulnerable to theories arising from different historical circumstances later on—since there is no absolute truth as a standard for saying one state of affairs is better than another. (Unless of course these thinkers were secretly depending on some universally accepted standard of justice or goodness or truth, which would then undermine their whole argument. Their problem is that, for persuasive reasoning to work, there has to be some foundational notion of truth that can’t be reasoned away. Reason has to have an unproven faith at least in its own foundations.) Reason is hardly enough to make manifest the whole of life—what life is—but without its assistance, there’s no way to understand anything.

In The Vollard Suite, Picasso depicts the claustrophobic nightmare in this rejection of transcendent wisdom, and reason as well. All of postmodernism, in the way it became a campaign of recognition and liberation for various oppressed groups reaches for this obviously admirable goal by rejecting any sort of universal truth. Truth becomes a mask worn by power. It is Nietzsche’s essentialist vision, subordinating human individuality and any notion of immutable goodness and truth to the needs of group identity, while equating group identity with the provisional, pragmatic seizure of economic and political power. The Vollard Suite plays all of this in the microcosm of Freud version of human nature, but similar claustrophobic dramas act themselves out in all the other spheres as well. This series of prints isn’t just Picasso’s almost involuntary critique of his love life and his art. It’s also a critique of the notion that humanity is about nothing but one fundamental drive or force—in Freud’s case, sexual conquest (or the repression and sublimation of the urge for it into art). Picasso shows the dehumanizing effect of any “essentialist” vision of human nature, even beyond the one that governed his own life. The only indication of wisdom and compassion in the series is climbing steadily out of the picture in his loin cloth—not completely gone, but unheeded and maybe unseen.

Comments are currently closed.