The $3.8 million snapshot

Recently, I heard from my friend, Sancho Panza, in Tennessee. (I love Tennessee because it’s hilly and beautiful and because Nick Blosser paints there. But I digress.) Sancho doubts. He mocks. He finds me amusing and occasionally annoying and generally thinks I live in a world of fantasy. Sometimes, he addresses the level of truthiness in my thinking. Other times, he’s dead wrong about whatever, but when it comes to the realm of art it’s refreshing to hear from him. He’s a sort of bollocks alarm. When something looks fraudulent in a groupthinky way, as it often does, in the empire of art, he just comes right out and asks “Who cut the Moose House cheese?” He spotted this item from Popular Photography and proceeded to ask why:

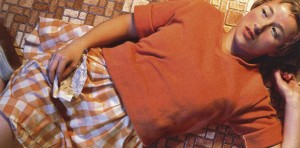

Cindy Sherman’s “Untitled #96″ from 1981 has become the world’s most valuable photograph after selling for a staggering $3.89 million at a Christie’s auction yesterday (it was estimated to be worth up to $2 million). The winning bidder was Philippe Segalot, a private advisor to some of the world’s wealthiest art collectors. The photo takes the top spot away from “99 Cent II Diptychon” by Andreas Gursky, which enjoyed five years as the world’s most valuable photo after selling for $3.35 million back in 2006.

Me: Yes, the auctions are hitting new highs. The bubble continues. She’s an interesting character.

Sancho: How do you explain what the bubble chooses?

Me: She’s been around for decades. She’s “established.”

Sancho: But then they randomly settle on one piece of work? This is what strikes the outsider as nuts.

Me: I actually like this photograph. But the reality is that it’s all arbitrary and subjective, and yet . . . I really do know the difference between pedestrian junk and, say, a Constable. There really is something genuine in a particular work you can see if you spend enough time with it.

Sancho: Okay. But I was hoping for some answers, an explanation of the seeming randomness.

Me: It seems random. It isn’t. You spend a year racing and you suddenly get better at it. Spend a year studying art or painting and you see the quality. And you see the fraud as well, in what’s high priced and not quality. But so much of what does sell high is just better stuff. The question is why does art matter that much . . .

Sancho: Yeah, why does art matter? But I don’t see how this photo can possibly be rated as not just better quality but quality worth millions versus thousands of other photographs.

Me: I could say some things but it probably wouldn’t help. It really is quite a good photograph, but the point is that you have to understand Sherman’s entire body of work. She takes endless photographs of her self in various guises. It’s conceptual. This would appear to be just her, no costume, not playing a particular role, etc. Like so much art in the past half century it depends, for its interest, on what people say about it, how it’s explained, what her theories are about what she’s trying to do, etc. All of which I couldn’t care less about. I want art that does all its work visually, without needing support from words and ideas. The artist gains an audience by doing something interesting consistently over a period of years, in a way which is distinctive–and very identifiable (that’s a hard part)–and then particular examples of this become judged as among the best of that person’s work and hence the value. If . . . the initiated say that the artist is among the “important” figures in a given period, then you set the stage for high valuations like that. It all makes sense. But you have to accept that what art has done over the past fifty years really makes sense and justifies the value placed on individual work like this photograph. I’m not sure prices like this will hold up, because conceptual art is becoming more and more suspect.

I think most people who haven’t spent years looking at art might wonder why a particular Vermeer is more valuable than another, or than the work of someone very talented who can paint just a realistically, say. I can see the difference and agree that Vermeer is greater than nearly anyone else who has ever painted. So the human value, the aesthetic value, of a particular work isn’t just subjective. It can’t be deconstructed away. Photography as art, though, is a big question, but at least you know that there are really great photographs and really crappy family snapshots, so you recognize a qualitative difference. Cindy Sherman’s work isn’t being valued for its technical skill. That’s a given. It’s what she’s doing with the skill and how it fits within her entire body of work, which has a lot to “say” about art and life etc. (This is where I tend to lose interest, when art starts “saying” things.)

Sancho accepted this, but actually he has made me agree with him, in the process. No single silver halide photograph should be priced at a level like this unless the process of dodging and burning, and other unique techniques in the dark room, gave birth to something that couldn’t be duplicated. The issue with photography is that, especially with archival ink jet prints, why is something that could, theoretically, be printed a million times be worth a large sum at all? Scarcity is part of what gives a great painting its supreme value, both monetarily and as a surrogate for life itself. It’s perishable and one-of-a-kind, like the person who created it. Photography rarely has this quality. To pay nearly $4 million for a Cindy Sherman . . . . I think I’ll pass and wait for the diamond-encrusted skull to rotate up to the auction block. I have a good jeweler who can give me a fantastic resale price for that one. (Oh come on. Don’t tell me the price of diamonds are artificially inflated as well . . . human kind can bear only so much reality.)

Comments are currently closed.