Polarities and Prince Myshkin

The novels of Herman Hesse were a hot item in the 60s, with their romanticism, their mix of Jungian psychology and Eastern mysticism and their hippie-friendly dreaminess. I read most of them when I was in high school. I loved the opening of Steppenwolf, the yearning of Harry Haller, the depressed, cerebral, central figure who takes a room in a clean, well-lighted boarding house and lingers on the stairs admiring the cleanliness and order of the home’s little windowed corners, all the attention devoted to middle-class comfort and restraint. He loved it because it was a levee against the tide of darker impulses and brooding that pulled him, throughout the book, toward a pyschologically liberating and dangerous life on the margins of respectability. Its tension between the passion for order and normalcy and the imaginative pull of the unpredictable is how the book fascinated me years ago when I read it. The other night, in an email, I read a quote from Mark Twain, sent from an acquaintance–“Be good and you will be lonesome.” It reminded me of Dostoyevsky’s Prince Myshkin, who was so good he simply uttered whatever he thought, without calculation, always telling the truth, or what appeared to be the truth to him, and the most fundamental truth he uttered was that “beauty will save the world.”

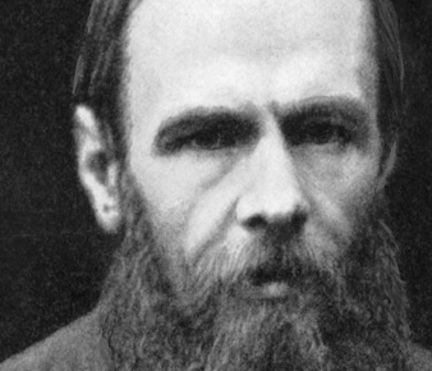

So I did a search for Prince Myshkin to refresh my memories about him and came across an out-of-print essay about him from Hesse, who was deeply influenced by Dostoevsky. To my surprise, it led me toward Hesse’s notion of polarity and how Myshkin himself was a figure who reconciled polarities by being rooted in something more fundamental than the world of opposites (in a Joseph Campbell kind of way). As Hesse puts it, about a scene where the prince is rejected by everyone around him:

On the one side society, the elegant worldly people, the rich, mighty, and conservative, on the other ferocious youth, inexorable, knowing nothing but rebellion and hatred for tradition, ruthless, dissolute, wild, incredibly stupid for all their theoretical intellectualism; and standing between these two groups the Prince, alone, exposed, observed by both sides critically and with the closest attention. And how does the situation end? It ends with Myshkin, despite the small mistakes he makes during the excitement, behaving exactly according to his kind, gentle, childlike nature, accepting smilingly the unbearable, answering selflessly the most shameless speeches, willing to assume every fault and to search for every fault in himself – and his complete failure in this with the result that he is despised, not by one side or the other, not by the young against the old or the reverse, but by both, by both! All turn against him, he has stepped on everyone’s toes; for an instant the most extreme social opposites in age and point of view are completely wiped out, all are united and at one in turning their backs with indignation and rage on the single one among them who is pure.

What is it that makes this “idiot” so impossible in the world of other people. Why does no one understand him, even though almost all love him in some fashion, where almost all find his gentleness sympathetic, indeed often exemplary? What distinguishes him, the man of magic, from the others, the ordinary people? Why are they right in rejecting him? Why must they do it, inevitably? Why must things go with him as they did with Jesus, who in the end was abandoned not only by the world but by all his disciples as well? It is because the “idiot’s” way of thinking is different from that of the others. Not that he thinks less logically or in a more childlike and associative way than they that is not. it. His way of thought is what I call “magical.” This gentle “idiot” completely denies the life, the way of thought and feeling, the world and the reality of other people. His reality is something quite different from theirs. Their reality in his eyes is no more than a shadow, and it is by seeing and demanding a completely new reality that he becomes their enemy.

What is remarkable and strange, important and fateful, is not that somewhere in Russia in the 1850’s and 60’s an epileptic of genius had these fantasies and created these figures. The important thing is that these books for three decades have become increasingly important and prophetic works to the young people of Europe. The strange thing is that we look at the faces of these criminals, hysterics, and idiots of Dostoevsky quite differently than we do at the faces of other criminals or fools in other famous novels, that we understand and love them so uncannily that we must feel in ourselves something related and akin to these people. This is not due to accident and even less to the external and literary elements in Dostoevsky’s work. However disconcerting any of his traits may be you have only to think how he anticipates a high-ly developed psychology of the unconscious — we do not admire his work as the expression of pro-found insight and skill or as the artistic representation of a world essentially known and Ihmiliar to us; rather we experience it as prophecy, as the .mirroring in advance of the dissolution and chaos that we have seen openly going on in Europe for the last several years. Not that this world of fictional characters represents a picture of an ideal future no one would consider it that. No, we do not see in Myshkin and all the other characters examples to be copied; instead we perceive an inevitability that says, “Through this we must pass, this is our destiny!” The future is uncertain, but the road that is shown here is unambiguous. It means spiritual revaluation. It leads through Myshkin and calls for “magical” thinking, the acceptance of chaos. Return to the incoherent, to the unconscious, to the formless, to the animal and far beyond the animal to the beginning of all things. Not in order to remain there, not to become animal or primeval slime but rather so that we can reorient ourselves, hunt out, at the roots of our being, forgotten instincts and possibilities of development, to be able to undertake a new creation, valuation, and distribution of the world. No program can teach us to find this road, no revolution can thrust open the gates to it. Each one walks this way alone, each by himself. Each of us for an hour in his life will have to stand on the Myshkin boundary where truths can cease and begin anew. Each of us must once for an instant in his life experience within himself the same sort of thing that Myshkin experienced in his moments of clairvoyance, such as Dostoevsky himself experienced in those moments when he stood face to face with execution and from which he emerged with the prophet’s gaze.

–1919

Well, it all led to a Nobel Prize, which he won for that last novel of his, so I’m willing to put up with the heightened rhetoric. Somewhere in there is the notion that polar opposites are just two sides of one . . . something . . . reality, which was what Campbell was always focused on, the unity behind everything perceptible. Any painter knows there’s no light without at least a little dark. And vice versa.

Comments are currently closed.