The aura of photorealism

Not surprisingly, the deadline for being an originator of photo-realism has long since passed, but photo-realism itself is still alive and well, though it doesn’t attract much critical attention. It was interesting and a little amusing to run across (in Wikipedia) these “rules” for determining whether an artist was an originator of photo-realism, or just a late-coming follower of the school. My response to Rule Number Three . . . well, yeah.

The word Photorealism was coined by Louis K. Meisel in 1969 and appeared in print for the first time in 1970 in a Whitney Museum catalogue for the show “Twenty-two Realists.” It is also sometimes labeled as Super-Realism, New Realism, Sharp Focus Realism, or Hyper-Realism.

Louis K. Meisel, two years later, developed a five-point definition at the request of Stuart M. Speiser, who had commissioned a large collection of works by the Photorealists, which later developed into a traveling show known as ‘Photo-Realism 1973: The Stuart M. Speiser Collection’, which was donated to the Smithsonian in 1978 and is shown in several of its museums as well as traveling under the auspices of SITE. The definition for the ORIGINATORS was as follows:

1. The Photo-Realist uses the camera and photograph to gather information.

2. The Photo-Realist uses a mechanical or semimechanical means to transfer the information to the canvas.

3. The Photo-Realist must have the technical ability to make the finished work appear photographic.

4. The artist must have exhibited work as a Photo-Realist by 1972 to be considered one of the central Photo-Realists.

5. The artist must have devoted at least five years to the development and exhibition of Photo-Realist work.

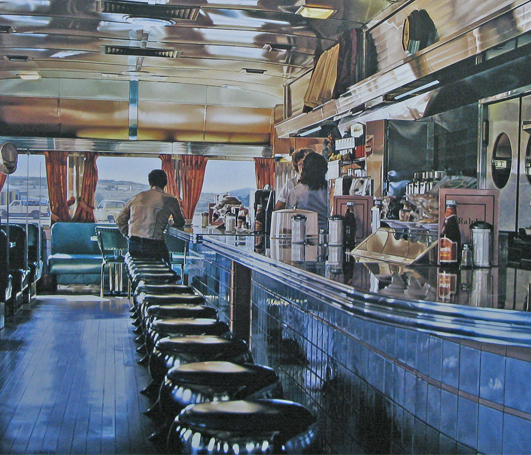

What’s missing in the way most people talk about photo-realism is the power it derives from its having been built slowly, with physical objects and substances, not simply because it’s an amazingly skillful duplication of a photographic image. Something essential goes into the painting, which wasn’t present in the photograph, even when the finished work looks like an exact replica of the photo. (Though even the best photo-realist work rarely looks exactly like a photograph.) I think what distinguishes the painting of an image captured with a camera (and this is obviously part of what makes Vermeer, the original photo-realist, great) has to do with the “aura” of an original work of art, which Walter Benjamin dismissed as something mass media had exterminated. Not so fast. The physical act of making a painting, one brushstroke at a time–whether it’s abstract expressionism or photo-realism or anything in between–conveys something tangible but difficult to name. It also alters the photographic image incrementally in a hundred small ways that have to do with an artist’s unique preferences and taste. If you gave the same photograph to two different photo-realists, you would be able to distinguish one painting from the other, no matter how similar they were, and those differences embody the unique ways an artist gets his materials to obey him, or doesn’t–and then learns to adapt to what he can and can’t do with paint. All of this gives a painting its personality, presence, and the sense that it’s somehow alive. The essence of a photograph, its vitality and power, isn’t tied to a specific physical object, in a particular place–I think it’s far more infinitely reproducible. A photo-realist painting brings the image back into the physical world. It’s as much an object on the earth as the person who made it, and the essence of a painting is connected to the limitation of its physical nature, which is also its unique advantage, and part of what essentially makes the great paintings so expensive. In their own way, they’re one of a kind, even if they look exactly like something that could have been reproduced a million times.

Comments are currently closed.