Modernism’s unrequited love

Louis Menand has a tremendous essay on T.S. Eliot in the current issue of The New Yorker, in which he offers a concise definition of modernism (and gives it a pulse in his portrait of Eliot). He points to the way this movement was desperately seeking to convey old verities in new forms, borrowing (stealing, Eliot would have put it) from the past, and then smuggling ancient insights in a new voice, for a fresher vision. Old wine into new skins. (It would be funny to see if Thomas Sterns would have turned a whiter shade of pale as you told him that he was the world’s first old-school hip-hop DJ, sampling tracks from the past to build something with a new sound, albeit one that’s deeply rooted in respect for tradition. Hip-hop is one of the ways in which modernism became, for a while, a forceful benevolent presence in the lives of countless millions, though most of its listeners would give you a blank stare if you told them so.) The resulting vision of modernists often seemed fractured—as in The Wasteland or Les Demoiselles d’avignon or The Rights of Spring—but the wonderful irony of modernism is that behind the apparently savage and dissonant exterior lurked an unrequited love for, and a faith in, fundamental and ancient truths and harmonies, even if they had become mysteriously resistant to interrogation, aloof and impregnable, like Kafka’s castle. That old fortress is looming overhead, up there on the mountain all right, it still presides, but you can never quite get inside and see the world from its parapets. (While the people who think they can get inside it generally become a menace.) You’re not sure it even knows who you are, living down here in the village. As Menand points out, for Eliot, only Dante was able to get into that castle and gaze to the horizon, comprehending the world in a way that would illuminate the landscape for his readers, and after that, for Western literature, it was all a slow disintegration into increasingly fragmented vernacular. That always makes me laugh, Eliot’s worship of Dante, it’s such a concise summary of his fanatical conservatism: to hear him say that everything after The Divine Comedy is a bit of a letdown. Yikes. So my love for Bottle Rocket, where does that fit in, exactly, Tom? Needless to say, Shakespeare wept.

One of the wonderful things about Menand’s essay is how he traces the virtual invention of the university English department back to Eliot. Eliot’s presumption, which is at the root of modernism, is that you need to understand as much as you can of English literature, back to Sir Gawain and Beowulf and Chaucer, in order to comprehend anything worthy being written at the moment. You have to learn how to read, in other words, by understanding what’s embedded in the history of the tongue itself—its tropes and stories and myths—in order to understand what a serious poet is actually saying. In other words, modernism is/was about invention and daring explorations of new forms, yet it was even more about trying to simply bring the living truth of ancient traditions to a new generation. We’ve spent centuries building into our language certain eternal truths: it would make sense not to throw away this vast network of meaning, right? To keep this embedded wisdom alive? I had a professor at the University of Rochester, my favorite, Leroy Searle, who taught the seminar on Blake that I took, and then, in my senior year, a class on literary criticism, and it was a valiant tutelage in the New Criticism, in close reading, and it was the best class I’ve ever sat through. We read only three works the entire semester, delving as deeply as we could into the links and connections and traditions that ran through the three of them: The Tempest, The Visions of the Daughters of Albion, and Second Skin, by John Hawkes. Occasionally, we would take a brief illuminating detour into something like The Man on the Dump. The upshot was that I came to look upon Second Skin as a wonder of literature, the black swan in the Hawkes oeuvre, standing apart from everything else Hawkes did, the way Beckett’s essay on Proust stands alone on a shelf of his plays and novels. I also remember how the tradition of alchemy, as a spiritual discipline—which Carl Jung wrote about so extensively—gives to both The Tempest and Second Skin, a set of metaphors that allowed these authors to invest the creative human imagination with a revelatory authority, as the Romantics believed, especially Blake. It was a riveting class, partly because you had to really pay attention to Searle, so many ideas could cluster together into five minutes of lecture. As close as we were to deconstruction in the way we applied critical tools to those three works, and yet what I really learned was how much modernism depends on a deeply conservative faith, the desire to preserve and extend and illuminate the most ancient truths. If nothing else, Eliot made this inescapable in The Wasteland, where he drew from the greatest philosophical traditions: Judeo-Christian, Hindu, and Buddhist, trying to show their common reverence for wisdom and love, and how, in their stripped-down mystical practices, those three religions become virtually indistinguishable. It was part of the insight that led Joseph Campbell to write his books on mythology–trying to show a set of universal spiritual truths common across all cultures–and it was at the heart of Jung’s efforts as well, trying to find these universal truths deep in the subconscious and its unity with the natural world. Aldous Huxley, in his corner, called it “the perennial philosophy.” Eliot lapsed into a more narrow Anglicanism as he aged, but his determination never flagged in the effort to invent new words to express the life of a what is, let’s face it, a pretty dull religion. Well, they’re all dull, and the dullness is part of the point, if you’re trying to wean yourself from a whole spectrum of tasty illusions.

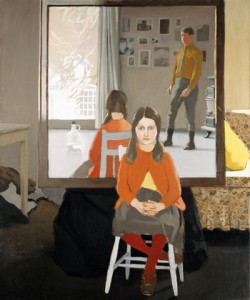

I guess this could be called taking the long way home, since I started out intending to talk about painting and how my favorite painters—Porter, Braque, Matisse, Manet, and most of the others I love—were all deeply in thrall to earlier painting and painters. This is nothing new, in one sense. Surrealism (and Cezanne) begat Gorky and Gorky begat Pollock/De Kooning and De Kooning has become a major influence in the work of dozens of painters, down to Jenny Saville as the Paint Made Flesh exhibition pointed out. Yet that superficial tracing of influence can easily ignore that what runs steadily down through these particular generations is a determination to convey the energy of the subconscious through the application of paint. And this common determination gives a deep urgency and significance to a later painter’s passion for the work of an earlier artist. Blake wrote an entire epic poem about his sense that he had become John Milton, in order to speak with the authority of that earlier poet’s voice and convey truths Milton himself wanted to convey but couldn’t admit to. He wanted to pick up where John left off, as it were. To keep the flame alive. Braque says that in his youth he didn’t just want to paint like Cezanne, he wanted to be Cezanne. The show about Cezanne’s influence on American painting in Baltimore and at the Montclair Art Museum nearly two years ago demonstrated that Braque was far from alone. Cezanne might be the single most influential painter who ever lived. And Picasso, Manet and Fairfield Porter idolized Velasquez and continuously looked back to his work as an unattainable standard. What drove them was love and a craving to do what the earlier painter did, without simply imitating him. Somewhere, Dave Hickey tosses out the suggestion that modernism and postmodernism might just be one and the same thing, but nothing could be further from the truth. After the sixties, the arts became more and more Balkanized, fanning out into a delta with a thousand shallow branches. At the same time they became more and more ironic, conceptual, dispassionate and skeptical. French theory injected a sedative of sardonic second-guessing into artistic effort, so that interpretation became not just needed, but maybe the entire point of the effort and the lesson at the bottom of it all: there is no truth, it’s all just a network of provisional meaning. The dialog with the past became a querulous debunking, a critique, a mockery, when with the modernists it was ardor, the suffering of unrequited love for a truth they’d inherited from centuries of previous sacrifice and labor, a reality larger than themselves, which they kept trying to represent in their work–to carry on with the ongoing construction–without ever quite being able to fully comprehend it. The truth was out there, or in there, and they just kept trying to show it.

Comments are currently closed.