Dean Mitchell

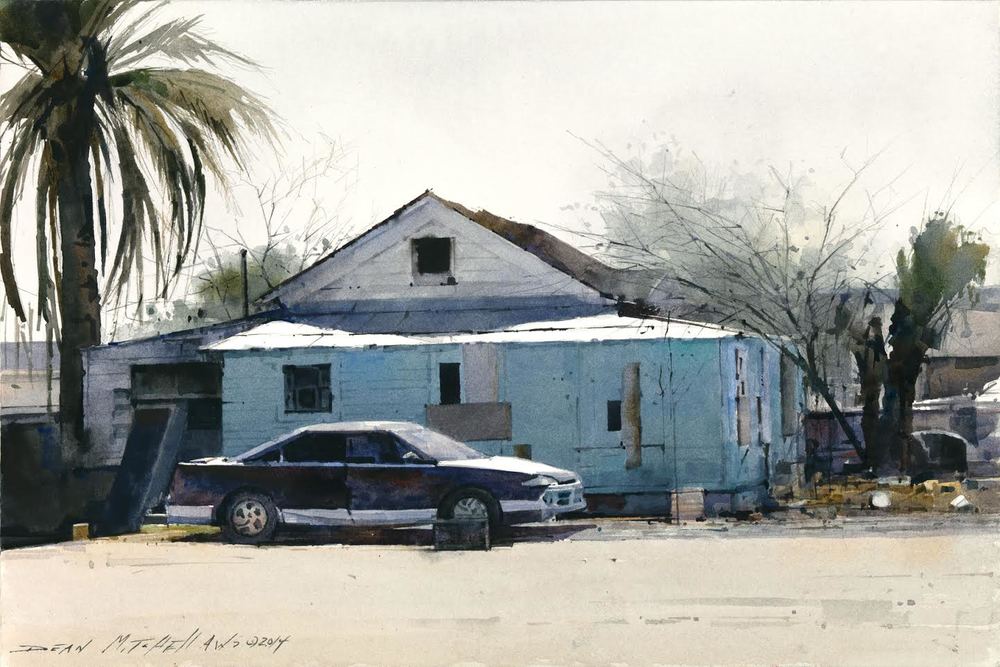

Parking on the Reservation, Dean Mitchell, watercolor.

There are certain painters whose work, the first time I see it, floods me with relief, the way I often feel when I walk through the door of my home after a long road trip. My burdens drop away because I can see, through the work, that everything I need is always at hand, in nothing more than, say, the way sunlight glares off the hood of a car. It’s hard to specify the burdens a painting like this removes, other than what my delight in nothing more than hazy sunlight would suggest: the fundamental human affliction of rarely being able to see things just as they are, being too busy in pursuit of something else not as real. In Dean Mitchell, whose work was recently exhibited at Exeter Gallery, this quality arrives with the mysterious additional blessing of his ability to show things in the world, times of day, the quality of light during certain months and at particular latitudes, as if this abundant, inanimate stage for the petty human craving to be somewhere else, or someone else, is itself perfectly sufficient to be just what it is and nothing else. With Mitchell, there’s no striving to impose himself, interpret, or curate for hackneyed beauties of landscape in favor of a drab bungalow, frail as a lean-to, under a palm tree. Through the title suggests it may be located on a Native American reservation in the West, it is exactly the sort of home one sees in abundance in certain Florida neighborhoods of Sarasota or Tampa or, I would assume, Quincy, where Mitchell grew up in a shack. It’s exactly the sort of place you wouldn’t even notice while taking a residential shortcut off Tamiami Trail on the way to Target or Home Depot. And yet in his painting it’s stunningly beautiful—without his having intentionally beautified the subject in any way. In other words, he has the utter humility and diligence of a photorealist, with scenes that have the instant verisimilitude a good photograph has, though he dispenses with all details that don’t matter through his mastery of watercolor. This is something the medium enables and almost requires. The brevity of the way he indicates clusters of leaves, in other hands, would have the predictable facility of a commercially professional work, but in his paintings it looks original, fresh, and discovered, even though it looks as if he’s hardly trying. And the way he knows what doesn’t matter, what he doesn’t need to show, and elides it into a wash of color with such easy efficiency, makes me envious, self-pitying, and full of awe, as if I were Salieri hiding behind a curtain while Mozart noodles out something immortal with only one hand at the keyboard, maybe eating a sandwich with the other.

Comments are currently closed.