Tilt-shift compassion

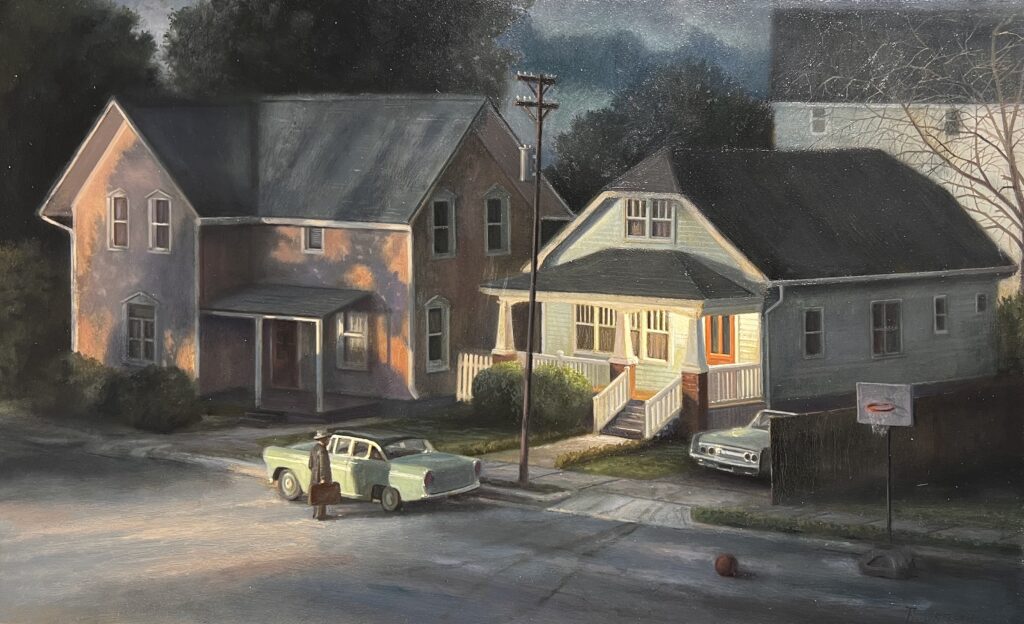

Landlord, oil on panel, 16″ x 26″

It’s hard to believe it’s been more than a decade since James Casebere’s photography was included in the Whitney Bienniel. I remember, back in 2010, being wowed by his reproductions of the suburban dioramas he painstakingly constructed and then lit and shot. His work seems to have gotten more austere and cerebral and political since then, but his landscapes of newly-built suburban dream homes still convey the ambivalent beauty of an increasingly unaffordable American Dream. Casebere centered the simplicity of his scenes at the median point between verisimilitude and minimalist geometry of newly constructed McMansions. His houses stand on an otherwise almost naked slope with newly-planted saplings a quarter century away from offering privacy and shade. Anyone who has lived in a new suburban tract knows the mix of feelings: the exhilaration of moving in, the weird sense of emptiness and exposure in a place without foliage, the smell of new construction and the sounds of new doors clicking into place, as well as the paradoxical solitude of tract housing jammed side by side into narrow lots. Casabere’s dioramas were about American life, as it is experienced by those lucky enough to buy a home—how much more poignant now in the current real estate market these scenes must be for young people hoping to put down roots. Yet his houses jutted up in various colors, evoking geometric abstraction, like the structures in an Icelandic landscape by Louisa Mattiasdottir. It was stunning work and it stirred many conflicted feelings—yearning, hope, and the inevitable disappointments of routine.

He was one of those art stars of the moment, using dioramas to make two-dimensional images, like Gregory Crewdson, on an even larger scale, whose constructed scenes—far more realistic and detailed—have a cinematic power and a darker, but even more alluring mood. Crewdson lives on the edge of popular culture. There’s a sense of epic effort in his illusions that seem imbued with an invisible presence. Built by hand and then captured with photographs, his work would be familiar to anyone who listens to Yo La Tengo (where I discovered it on one of their album covers) or watched Six Feet Under. His art was mentioned on the show, and he was recruited to do a promotional campaign for it.

It’s been years since I’ve looked into diorama art, so it took me a while to even come up with Casebere’s name, even with Google, yet the current exhibition at Arcadia in SoHo demonstrates that at least one artist is pushing the genre into a more narrowly defined scope, and the results are wonderful. They are also in great demand. The show sold out immediately. What’s most astonishing, though, is that it took Alberto Ortega only a year to build his dioramas and then paint all the scenes based on them for the show. Producing a solo show at this level in a single year deserves hushed respect. Ortega uses his own carefully arranged dioramas—lit in a distinctly personal way—to create oil paintings that hearken back to Edward Hopper. He keeps things far simpler than the more spectacular photographic work of Crewdson and Casabere, but Ortega is just as cinematic. Like an early hip-hop artist, relying on the bricolage of samples lifted from earlier recordings, he buys props made for model train enthusiasts and then assembles them and puts them into a new context—through their arrangement, their color and their lighting—to work his magic. At Ortega’s new Arcadia Contemporary solo show, Stephen Daimant answered a few of my questions. He has built an uncompromising engine of profitability on the demand for extraordinary painting, moving from downtown Manhattan to Culver City and Pasadena and then back to West Broadway during the pandemic. I asked him if the Spanish painter built his own houses. No. He buys everything he needs ready-made, marketed for model train enthusiasts. He finds what he needs and then makes you see it in a personal way—more like a still life artist than a painter of landscapes. In arranging the structures, the figures, and the skies he creates as backdrop, he transcends the everyday feel of the clean, well-lit place that model train enthusiasts tend to build as a setting. What sounds like a quick workaround to avoid the labor that Casebere would put into making a paper house provides an essential simplification of form. The cars date back sixty or seventy years. The little suited traveling salesman, standing by his parked car and contemplating his limited income and lean prospects, clutching his brief case while the sun sets behind him—his tiny faceless head gives the impression of some lonely, dogged worker, a Willy Loman who only wishes he could be the man in the gray flannel suit with a corner office. This is Samuel Beckett-land, with white picket fences. This is Plato’s world of Forms, if Plato’s demiurge had been a six-year-old boy building the world in a corner of the family room.

Much of what makes these paintings work resides in the choices he makes in lighting his scenes with great care, using subtle angles that accentuate the contrasts between light and dark and helping to additionally obscure unnecessary detail. Foliage is reduced to a dark mass of beautiful deep green. Things are spot-lit, as if on a stage, but somehow the lighting doubles as angled sunlight, leaf shadow, the color of a late sky reflecting off a wall, or unlikely streetlights that mostly remain out of view. Ortega’s ability to control multiple sources of light gives him a way to accentuate the stark three-dimensionality of the props, everything arrested, caught in amber, the past alive in the present, offering a sense of loss and yet a strange sense of connection between the viewer and the subject, a personal bond, as if remembering things you’ve never experienced.

All minute detail is shorn away of necessity, because the props don’t bother with it—there is no attempt at hyper-realism and the generally convincing impression of physical reality vies with a tilt-shift effect of subliminally recognizing these objects as they are, at the scale of toys.

The experience of looking down at these little scenes of ordinary life makes you feel protective of them. You feel an involuntary empathy with such little figures, almost wishing you could make their lives easier, or keep them company, wherever they are going. You want to go down and give them a hand, the way Clarence wanted to give George Bailey a hand. It’s not a feeling one gets very often in an art gallery now, let alone in a mall. It’s marvelous.

Comments are currently closed.