The texture of nature

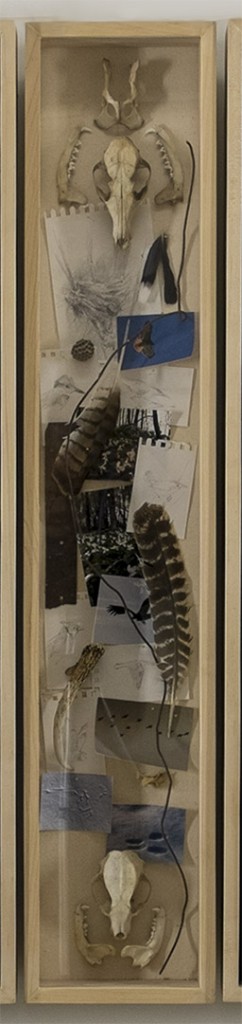

A show of Rick Harrington’s paintings opened a few days ago at the Vilona Gallery in Boulder, Colorado. Rick, and his son Todd, met me at the Gatehouse for lunch last week, followed by an hour-long tour of the Memorial Art Gallery. As a road warrior, Rick is my hero. He has logged many thousands and thousands of miles, tens of thousands probably, driving his work to juried fairs around the country. He works hard and then plays hard, too, fly fishing or whitewater kayaking somewhere within a drive of his shows out West and elsewhere. His painting and his immersion in these recreational ventures into the wild are two sides of one activity for him. Someone clever might be able to make the case that they may simply be one activity viewed from two different points in time. He says the process of exploring and interacting with nature, as a prelude to the painting, immerses him in the world, while en plein air painting makes him more of a static observer. His most ambitious work so far has been a series of large, quasi-abstract landscape paintings attached to windowed boxes full of natural artifacts he has collected from the particular place depicted in the painting. (It reminds me of Burchfield’s quirky, obsessive attempt to depict sounds and other non-visual sensations in his paintings, all in the hope of triggering a deeper identification with nature in the viewer). For the past sixteen years, Rick has relied exclusively on his painting for income. His wife, Darby, is a college administrator and a writer, and her steadier income has balanced the ups and downs of Rick’s. Since 2008, the battle has been tougher, but he’s still making it work.

We talked about the shows I’d seen in New York City, and Todd agreed that Donatello was not only one of the greatest sculptors in history, but also one of our favorite Ninja Turtles. Rick can be hard to hear in a crowded restaurant. He has had surgery twice on his vocal cords and his raspy undertones are in the Jack Bauer range, so you have to put down your smartphone and lean in and focus when he speaks. I asked him why he started doing these large landscapes after having so much success with his abstracted barns.

Rick: Five years ago or so I was looking at galleries, and they were responding more to the landscapes than the barns which was good as far as I was concerned. It would go really well, but at the last minute they would say, but we’ve got this other guy. I would look at what they were talking about. I wouldn’t necessarily see the similarity so much in the work but the similarity for the purpose of selling: the same palette, whatever.

They would say someone who would buy this of yours would buy this other guy’s.

Rick: Right. Which is not at all what I think about when I work. Selling. At the same time, I had to take it into account. That got me started questioning why I was doing what I was doing.

Questioning the barns?

Rick: No, just straight landscape. At the same time I had to deliver a painting down to the Hudson Valley and we stayed overnight and went to Dia Beacon. We saw Richard Serra’s work. There’s that piece like a ship’s prow that blew me away. Then we went to an upper level that had been a turntable where they used to turn locomotives around. When we walked in there, I thought God, I have to work big. Same way I felt when I saw Rothko for the first time. Back then I wasn’t a good enough painter to do it. The old saw is if you can’t paint, paint big. But if you paint big, and you can’t paint, it just sucks, really big. To paint big, it’s hard.

Scale makes it completely different in terms of the brushwork.

Rick: You have to paint so boldly. I’m determined to try a new application of paint. The marks I’m seeing in my head, I have to use big knives or cardboard with cloth over it to hold the paint. I want really big marks. It’s like painting at the outer edge of my ability. It’s paint as its own language. The idea really is, I want you to feel you’re inside the view.

Be inside the scene.

Rick: The ones I’ve done so far up to 12 feet . . . it’s frustrating. That the 12 feet isn’t large enough, that to paint even larger is so much harder, and that it’s all such a gamble–that’s the frustration.

You’ve seen Welliver’s work in person, right?

Rick: Yeah. It’s a constant battle. That piece I put up in that buyer’s home. That painting in that kitchen is four by five feet. It doesn’t look that big. It’s a huge kitchen.

It thought it was a dining room, from the picture.

Rick: That power of scale and then to me not only do you want the image to be compelling, as you move in, do you want the paint itself to be compelling?

Rick and I have had discussions of Walton Ford’s work along these lines. We’re both great admirers of his originality, and with Rick, Ford’s recurrent theme of humanity vs. nature strikes a basic chord. Yet both of us had the same reaction when we’ve seen the work at Kasmin—a reaction I’ve had to some of my own finished paintings as well—where, when you get up close, the way the paint is applied feels disappointing. It’s shorthand that works perfectly from a distance. Yet when you get close to the surface, and it sounds ridiculous to put it this way, but it feels as if he’s disrespecting the paint. In Rick’s terms, the paint isn’t it’s own language, but is completely subservient to the idea and the image Ford is creating. There’s no sensuous commitment to the energy of the paint on the surface—as nothing but paint. It’ll never be an issue for a collector or a critic, when it comes to Ford, but whatever felt lacking at that up-close range in those paintings, this is what Rick wants to be sure is present in what he’s doing now.

Rick: Darby and I went to a beer-tasting dinner with a college friend the other night, and we sat with a professor and a friend who are both psychologists, and we talked about what we all did. They said “what do you do?” I said I’m an artist and was going to let it drop, but Darb asked me to get my phone out and show them. One of them immediately—on the iPhone you can keep enlarging the picture–she said, “that texture is like you’re there. It’s like you’re in the woods.” It’s what Van Gogh was trying to do: to paint the tactile feel of being there. But to me it’s what I like about being outside, all that stimulus calms my head down. It’s what I love about kayaking.

Embedded in that little anecdote, with most of the connective tissue missing, is Rick’s argument for being a painter, as well as his hunger to do it. First, it’s a reason to be outside where the rush of stimulation feeds his A.D.D. sufficiently to calm his mind and reconnect him with the silence of nature. (Painting is one justification for going outside, probably down on the list beneath the fishing and the kayaking.) Second, to experience a place with such intensity that he can convey it in a number of different ways through the act of painting, not simply by getting a viewer to see a representation of the landscape as Rick saw it, but also to apply paint in a way that also conveys the energy of the natural world, as Van Gosh did with his brushwork.

So I asked him how he got from the larger landscapes to the boxes.

Rick: The question, why the larger landscape paintings? Why do I have a bag of rocks and bones with me when I come home from Alaska? When we first moved to South Lima out walking, I found this nice granite rock weighed about 80 pounds. Beautiful orange granite. I carried this rock home two miles. I could carry it 150 yards and then my forearms were so shot, I’d put it down. I’d say, “Take the dog. I have to get my rock.” What? “I’ve got this rock.” Walking along, Darby said, “What are you doing?” I would just drop it. You can’t even use your hands after a while it’s so heavy. I started thinking, wait a minute. I started shoving it under some brush. She said “What are you doing?” Hiding it. “Who is going to want that rock?”

I’ve always been a pack rat that way. Why? To anchor myself in that place. So I started working with that. Sketches, found stuff, casts I make, skulls and bones and rocks. I cast grizzly tracks. I take plaster with me and gauze and embed the gauze in the plaster. When I was a kid I used to do plaster casts of animal tracks. And they all got thrown out. I’ll be with guys around a campfire drinking and I’ll walk away to cast some tracks. You’re an idiot! The next morning though, it blows them away.

You were saying before that this whole series of paintings is a sort of an ecological campaign on your part. . .

Rick: Yellowstone. We were at Yellowstone. It’s like the first time you’re in Yosemite and you’re looking at granite cliffs as tall as Manhattan. You get to the point in Yellowstone, especially as a kid you get up at dawn. Hardly anyone who goes to Yellowstone does that. People are out there all afternoon but the animals aren’t there. They’re all bedded down because it’s hot. You have to go out early. So we had had lunch and walked into an exhibit. Came across a permanent exhibit of Thomas Moran’s work. He went on an early expedition to Yellowstone and he did a bunch of sketches and paintings, and they used those to help convince Congress to establish the park.

Suddenly you’re a Hudson River painter.

Rick: But with the AbEx influence.

I didn’t mean you, I meant anybody, looking at Yellowstone.

Rick: I can’t wait to go back to Yosemite. I took photographs but didn’t even stop to sketch. Photographs cheat the scale. The first time I realized that was when I was scouting whitewater. You take a photograph and look at it at home and you lose the scale. For a long time I was afraid to paint Letchworth Park. I was afraid of getting bogged down in the details. I came home from paddling one day and realized I could paint it. Part of it was just being ready to paint it. That was really my own evolution as a painter–the evolution of the way I interpret what I see.

Behind all of it is the hope that the painting can wake people up to nature.

Rick: That book The Last Child in the Woods. One possible response to A.D.D. is to take kids outside. To me kids are just like dogs. Wear them out. Coaching soccer you get kids all amped up for a game. I’d make them run laps before the game. Parents were complaining, “You’re going to wear them out.” I didn’t care. Show me a ten year old fit enough to play soccer, all you’re going to do is take the edge off. I’m a frustrated environmentalist. If you want to have a conversation that wins the average person, screaming won’t do it. My hope is, like with this Alaska painting, which still scares me to try and do it. I might put $500 dollars worth of paint into it. This last one, I like the paint. If I’m afraid of messing up, I don’t paint well. If I can do a painting compelling enough, beautiful enough, experiential enough, I hope it makes the argument to preserve a place. Many places.

You have to be in that little zone where you’re fairly confident but not quite sure.

Rick: To me it’s sport. You practice and practice and practice. Quit worrying and play. If you’re scared running whitewater, no. If you’re confident in your preparation you can be so fluid that you can be your best self. The first terrifying swim in whitewater I took, like Biblical flooding water. When I swam I got rescued by a power boat. Then I watched a raft, guy went through it backwards, didn’t take a stroke. He knew the path so well. And was so confident. Like any sport, all the practice builds familiarity, and you can leave behind the tension of performance and just play your best, but in a relaxed way, completely free of the concerns about making mistakes.

Afterward, we went across Goodman and wandered around inside the Memorial Art Gallery, and I’m always amazed at how extensive the collection is, how you can live in a community the size of Rochester and drive only a few miles to see a Rembrandt or Titian, Bellows, Porter, Kensett, Homer, Thiebaud. We wandered upstairs and paused briefly in front of a contemporary Chinese scroll painting. It reminded Rick of a dam that will be built in China and he started talking about the effect of dams on the environment—illustrating even more effectively how there’s no way to separate his devotion to nature and his devotion to painting. While we had moved on to a display of seppas, spacers for samurai swords, he was still talking about salmon and the ecological balance of a watershed that depends on them:

Dams are problematic on lots of levels, from the weight of the water behind a damn that size (and the affect that weight has on the bedrock surrounding it), to the elimination of the annual flood cycles, to all the consequences regulated flow has on the downstream ecosystem in ways that are never even thought of ahead of time. In terms of the environment, the Three Gorges dam will destroy a whole ecosystem. Politicians and business people want to say we can’t afford to miss those money making opportunities, but don’t seem interested in any long-term effects, the downside of development, which is often so complex and interwoven, so far reaching, that they can’t be imagined.

Dams disrupt salmon runs in the Pacific Northwest and in British Columbia with the decline of fisheries. Salmon provide a massive import of biomass from everything they eat in the ocean. All fattened up they return to their streams, where they die after spawning, and provide a massive protein dump–hundreds of millions of tons- that is the basis of so much of the food system in each river drainage. From maggots and worms up through bears, wolves. You can detect old salmon DNA in trees. The whole ecosystem developed based on that over centuries, and we decimated it in 75 years. Damns have all but eliminated the natural runs, for a host of reasons. The fry get damaged dealing with the damns downstream, and become easier prey in their weakened state – it goes on and on… to say nothing of the barriers to returning fish making it all the way back up to the spawning grounds. Runs in the Columbia system are thought to be about 5% of what they once were. Imagine how much food there would be if they were back to that level. And the hatcheries touted as the solution turn out to be even further damaging to the native fish, in terms of competition for resources, and possibly most problematic, homogenization of the species. Each creek, each river, has a strain of fish unique to it- affecting the timing of runs, the size of the fish, the path of migration, etc.- that keeps the species as a whole broad enough in characteristics to adapt to environmental calamities. We have narrowed it all down to whatever is most efficient to raise in pens, and dropped duplicate fish into all the streams. Primarily supporting the commercial fishing industry, where the big lobby dollars come from. Salmon farming is another topic all together.

Comments are currently closed.