Earth, sky and water

There’s a little more than a week left to see Among Untrodden Ways at Oxford Gallery, and it’s well worth the time to get there before it closes. Sean Witucki, Charles Houseman, and Ken Townsend are all working in the same stylistic neighborhood, but each of them has a distinctly individual vision.

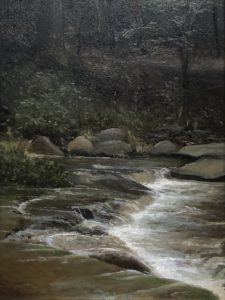

Of all the work from Witucki in the show, the standout is a small oil, only a foot in height, Wolf Creek After the Rain. The way he renders the water of the creek purling over the shallow ledge of laminated shale so common in Western New York is remarkable. Anyone who has hiked the Finger Lakes will recognize that hardened prehistoric mudstone, once the bottom of a sea, under such a thin layer of fresh water. The color of the water, from ochre to olive and then to a gray/greenish blue where it recedes to the far rocky bank, is amazing. The little fringe of foam, harmless whitewater to a wader, beckons to the viewer, but it’s what’s below that remains enticingly visible, an inviting but risky submerged surface, seen through ripples and reflections of the sky. He manages to capture that sense of being able to look into the water down to the slippery face of the creek bed—there’s more trouble here than the shallow depth would suggest. One wrong step and you’re on your back. The woods beyond are done with Corot-like flicks of the brush on soft masses of color. The image conveys a rapt, luxuriant pleasure in the paradoxical stillness, the restfulness, of water that never stops changing but always seems the same.

York is remarkable. Anyone who has hiked the Finger Lakes will recognize that hardened prehistoric mudstone, once the bottom of a sea, under such a thin layer of fresh water. The color of the water, from ochre to olive and then to a gray/greenish blue where it recedes to the far rocky bank, is amazing. The little fringe of foam, harmless whitewater to a wader, beckons to the viewer, but it’s what’s below that remains enticingly visible, an inviting but risky submerged surface, seen through ripples and reflections of the sky. He manages to capture that sense of being able to look into the water down to the slippery face of the creek bed—there’s more trouble here than the shallow depth would suggest. One wrong step and you’re on your back. The woods beyond are done with Corot-like flicks of the brush on soft masses of color. The image conveys a rapt, luxuriant pleasure in the paradoxical stillness, the restfulness, of water that never stops changing but always seems the same.

Charles Houseman has contributed more than a dozen of his newest paintings to the show, and I reacted most strongly to the most elemental, his vision of the Maine Coast, Great Head at Low Tide, where rock, sky, trees and tidal pool compose a scene that—like Townsend’s shale—could have remained largely the same for a hundred thousand years. It perfectly captures the way the Maine coast seems assembled—or rather dropped into place by a receding glacier—to repel anyone who isn’t standing on dry land, while still inviting you through a jagged gauntlet of stone with its hazy beauty. One of his smaller paintings, Newton Farm, was a minimalist composition with a small strip of land beneath a blue void, an apophatic affirmation of energy through the absence of everything inessential, both pictorially and for anyone actually standing out in that open field, taking it all in.

The revelation for me in this show is Ken Townsend’s assured versatility, where nearly every painting looks utterly natural while being carefully, masterfully designed. It’s his first appearance at Oxford and an auspicious one. Most of his paintings can be broken down into four areas of comparatively uniform value that lock together like a simple puzzle, with all the detail rendered as variations within that particular value—darkest, second darkest, second lightest and lightest. The way he gives each of these areas a clearly defined contour, compositionally, makes the paintings so visually powerful. It also enables him to emphasize and augment the color in each of these areas almost as an abstractionist would. He could push this even more than he does, but when he allows himself some rich hues, the colors are  beautifully chosen, deeply felt. This is readily apparent in work like Gardner’s Road and Mendon Ponds, an overhead glimpse of water lilies, with one small white blossom serving as the tiny, lightest section. Yet a second painting of probably those same water lilies, Dar Reflected, is a perfect example of how Townsend is able to lay down areas of vibrant color by emphasizing and unifying those four areas of value and working within them as a structure for the image. All the viewer sees is a flat stretch of violet water, reflecting the sky, throughout most of the lower half of the painting, broken up by a cluster of lilies with one blossom, and then in the upper half of the canvas, the reflection of the dark woods and at the top, what appears to be the rippled reflection of a two-toned kayak with a slash of pink for the paddler. Keeping out of view what would have been the subject of the whole painting for most painters (Eakins, for example) is what enlivens the entire scene. The brilliant blue and green of that reflection draw your eye and then leave it wanting, hinting at what’s almost visible, so that what you actually see feels more like a memory or a dream of something even more alive than what’s available to the eye.

beautifully chosen, deeply felt. This is readily apparent in work like Gardner’s Road and Mendon Ponds, an overhead glimpse of water lilies, with one small white blossom serving as the tiny, lightest section. Yet a second painting of probably those same water lilies, Dar Reflected, is a perfect example of how Townsend is able to lay down areas of vibrant color by emphasizing and unifying those four areas of value and working within them as a structure for the image. All the viewer sees is a flat stretch of violet water, reflecting the sky, throughout most of the lower half of the painting, broken up by a cluster of lilies with one blossom, and then in the upper half of the canvas, the reflection of the dark woods and at the top, what appears to be the rippled reflection of a two-toned kayak with a slash of pink for the paddler. Keeping out of view what would have been the subject of the whole painting for most painters (Eakins, for example) is what enlivens the entire scene. The brilliant blue and green of that reflection draw your eye and then leave it wanting, hinting at what’s almost visible, so that what you actually see feels more like a memory or a dream of something even more alive than what’s available to the eye.

The Townsend painting that knocked me out, though, was a very small square one, Roadside I, executed with palette knife. The technique, though rougher and more approximate than any of the paintings done with brushes, creates a snowy embankment almost more visually convincing than anything else in the show—with a tremendous sense of clarity. Again, he’s broken down what he sees into continuous areas of value, the darkest, a line of trees on the horizon, then the brightest strip, in the patchy snow just beneath it and then, above and blow these two tiers of color, the cerulean sky and a violet reflection of the sky in the snowbank, sharing almost the same value, with a triangle of road at the bottom, the second-darkest region of the image. He captures everything perfectly, the low sunlight scudding almost horizontally across the embankment, the becalmed sky, and the purple shadows that look scraped into the soil and driven over by a plow or a truck, yet without any indication of exact detail in the thickly scumbled paint from under his knife. The eye sees what it expects to see though it isn’t really there. He works into the image not just the purple of the snow and the classic blue of the sky but a little strip of orangish growth along the tree line, a color also breaking through the snow in the foreground, that makes the other colors sing a little more distinctly. It’s a perfect painting, hopefully hinting of more to come.

(Note: for fun, see if you can find the one Witucki painting in the show that bears the same title as an old Pearl Jam song.)

Comments are currently closed.