Archive for July, 2012

July 29th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Radicchio from Ithaca, oil on linen, 16″ x 36″

We bought these on a trip down to the public market on Cayuga Lake, in Ithaca, a few weeks ago and I was fascinated by the elongated shape and variegated color, as well as the twists and flares in the leaves. I wish I’d asked how the vendor grew them. I’d try some myself next summer. Our lettuce is just about done, but the cherry tomatoes are starting to get red.

July 22nd, 2012 by dave dorsey

Poultry for Smithfields, Sarah F. Burns

When I saw this, it reminded me of two different paintings by Chardin (also involving game birds one step away from the oven), both in the choice of subject, the simplicity of the staging and in the handling of paint. Great work, part of an interesting and compelling series of vanitas paintings by Sarah F. Burns in Oregon. At one point, the project involved dragging a bloody bear carcass into her Ashland studio. This woman is serious about her meat. And her art. Her friend Jennifer Nitson interviewed Sarah and came away with a nice small profile of the artist containing a wonderful, illuminating quote: “I have been particularly interested in small-scale meat production and nose-to-tail eating because I grew up in that type of lifestyle. My father was a farm-kill butcher when I was born. That means he went from farm to farm killing livestock and brought them back to the butcher shop to cut up and wrap.” The work was commissioned by a local restaurant in Ashland, named after a London market. As Sarah puts it on her blog: “Smithfields is . . . named after a London meat market with a very long history, going back to the middle ages where it was the place of public executions, becoming a livestock market, and is currently a wholesale meat market today.”

It’s sense of timelessness is what especially appeals to me about this work. It could have been painted two centuries ago and yet it looks totally contemporary as well. I guess that last sentence is just a long way home to the word classic.

July 18th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Kehinde Wiley’s “Abed Al Ashe and Chaled El Awari (The World Stage: Israel)

My visit to Chelsea a couple of weeks ago turned up a surprising number of shows with religious content, presented in vastly different ways. I’ve already pointed out the quasi-Gnostic overtones of the Joseph Strau show at Green Naftali, which seemed to be a sincere attempt to produce art inspired by the German artist’s personal spiritual awakening, but at least three other exhibits approached religion in three distinctly different tones. At D.C. Moore, Beasts of Revelation offered a variety of interesting work, but the tone of the press release created a snarky lens through which it was nearly impossible to see any of the work as a genuine attempt to visualize religious faith in a non-judgmental way. Christopher Hitchens, if you’re watching, you should be grinning. The release was more than a bit pretentious, heralding that the show would break new ground into content heretofore taboo for contemporary art. Oh, that again. (Is that even remotely possible anymore?) The fact that, simultaneously, three other exhibits elsewhere in the city were infused with religious content offered a deflating reality check to this bit of bloviating on contemporary art’s ability to “pose uncomfortable questions and provoke disturbing answers.”

What the show appears to be is the gallery’s attempt to visualize what it calls . . . wait for it, wait for it . . the “insidious aquifer of metaphorical power” exerted by “religion” but what’s clearly meant is right-wing Christianity. “Political issues that might have been considered personal during another era have become rallying cries for various religious groups.” It isn’t hard to translate what that means, and some of the idiocies of the Christian right-wing are easy targets for anyone who wants to pound the drum over their knuckle-headedness. Yet a show about “religion” that might have been far more interesting and resonant would have been one with images from Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist artists, as well as Jewish and Catholic, or maybe even a die-hard Taoist. Or a Rastafarian, anyone? A show that contained sincere images about personal faith: now there would be something that felt like a violation of a more genuine taboo, since we’re talking about More

July 16th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Very funny from Hyperallergic. A sample:

LeWitt’s paintings are clearly about making . . . anyone can make a Sol LeWitt painting. It might suck, mind you, but it’s still a LeWitt if it follows the instructions.

LeWitt’s conceptual approach is one of collaboration and is all about erasing, not only art as an object, but also the author himself. Because of this radical turn, one can say that he is seen as one of the most important artists in the conceptual art movement.

In fact, one should say that. You can usually get away with making a claim about who is “seen as” “one of” the most “important” anything — since these qualified phrases exempt you from having stated any facts. When a speaker says that X is seen as one of the most pivotal yadda, they actually mean to say something like, “Woohoo! I love this artist!”

However, in the case of Sol LeWitt, you can genuinely see that he paved the way for a whole new way of talking about art in terms of the concepts called up by viewing and or making it.

In fact, LeWitt’s new lexicon opened floodgates to a vast realm, a Pandora’s Box, one might say, of artworks that needn’t even be realized in order to be appreciated, and even bought and sold.

July 16th, 2012 by dave dorsey

July 14th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Joseph Strau, Exercises ab initio

“Josef Strau A former proprietor of well-regarded project spaces in Cologne and Berlin as well as an artist. Strau is known for combining aspects of automatic writing and automatic drawing into installations and sculptural ensembles that often include household furnishings—most notably lamps, which are something of a signature element for him.”

That’s the dictionary definition of Joseph Strau you can pick up at Greene Naftali, where you can inhabit his new conceptual installation until Aug. 10. That hand-out made me laugh when I got it home and read it, and laughter is so often my response to contemporary art, whether I’m laughing with the art or at it. Bottom line: I kind of liked the show, but I’m liking the guy who appears to be behind it even more than what he’s done here. If he’s real. Can you tell anymore? The ethereal quality of show makes you wonder if it’s all just a put-on, but I’m going to assume it’s sincere. It appears to be about recovered innocence, and it has a sense of rebellious spirituality you could trace back through the Hippies and Beats, on backward through Thoreau and Emerson and Rimbaud, all the way back to More

July 11th, 2012 by dave dorsey

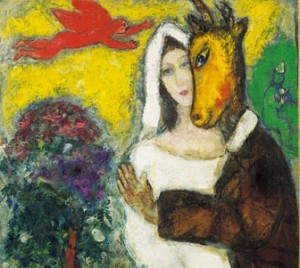

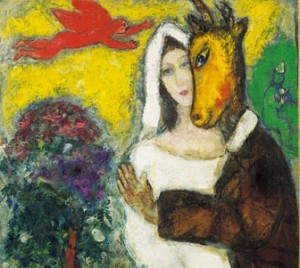

Midsummer Night’s Dream

I want a painting to be as insignificant and perfect as a daydream. I want insignificant perfection.

July 9th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Fait II, Claudia Fainguersch

I spent most of Sunday helping to hang the new group show at Viridian Artists, on W. 28th St., juried by Chrissie Iles, a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It was interesting to watch her silently visualize how each piece would look, deep in thought, while the rest of us moved pieces from one wall and to another and then often back onto the original wall, at her request. She required the center of each piece to be exactly 57” above the floor, so I helped Bob Mielenhausen, a fellow Viridian artist, in measuring each one, then bisecting it with a little plastic dot sticker. We then held up each painting to align the sticker with a levelled mark running along the wall at that height. It was something I’d never thought to do before: having the center of every work at exactly the same height in relationship to the floor and the viewer’s eye. No doubt it’s the most elementary rule in the curatorial book, but it was nice to finally learn it. It really made a difference in the look of the whole show when we were done.

As all of this went on, Chrissie was sensitive to distractions. “I don’t want to see those phones,” she said at one point, referring to a diptych involving a cell phone and a more traditional handset. So I would move them out of her sight. Same with a couple other paintings that seemed to keep getting shunted off to some place out of view. I was beginning to feel their pain. I’ve been ostracized; I know what it’s like. Finally, though, she would hit on the exact spot for a particular work and up it went, never to be reconsidered. Those seemingly neglected phones, in fact, were the first to find their home, long before everything else in the show. But for a long time, it was, “Just move that one somewhere else.”

She specializes in film, as well as film and video installation, and Minimalist and process-based art of the sixties and seventies. She is part of the curatorial team formulating the overall artistic policy of the Whitney Museum. For our day’s work, I joined our director, Vernita Nemec, her assistant director, Lauren Purje, and Bob. It took us six hours, from start to finish, with an hour break for brunch at the Half King a couple blocks away, where you get free Bloody Marys with your meal, their tomato juice loaded with bits of shrimp and hot sauce. When Chrissie came back from a long phone call from Europe, she started telling us about her close friend, the legendary international performance artist, Marina Abromovic.

Chrissie Iles

“I’m currently writing the text for a book on her performances. I did her first retrospective at Oxford,” she said, giving us a lot of background about how close the Abromovic family was with Tito in Yugoslavia, before it broke apart along ethnic lines. “The key to a lot of her work was her mother. Really rigid woman. Really awful.”

I wanted to hear a lot more, but our conversation was kept short by her long conference call with Europe and the need to finish hanging the show. Whan we got back to the gallery, the level of care she continued to put into every detail of our group effort impressed me enormously. The work was of varying quality, with many well-realized pieces More

July 6th, 2012 by dave dorsey

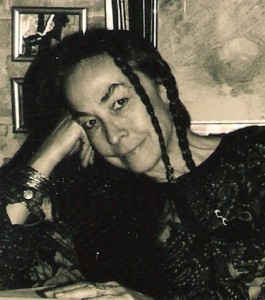

Vernita N’Cognita

Vernita N’Cognita is heading to a 16th century castle in a little town near Frankfort, Germany next month for a new performance, with a partner this time, David Rodgers, and she’s trying to raise money for the trip through Kickstarter. In this evocative Old World location, they’ll explore the clash between the European past, with it’s traditions and rituals, and the 21st Century world. They’ll attempt to portray the conflicts and contradictions we all face on a daily basis. Their performances will be a mix of theater, music and dance.

The work will be called “Trail of Sighs and Whisper,” and will be as feminist as most of her work and, from the way she describes it, slightly mournful about the sadness of human relationships. She’ll perform at the town of Homburg, at the invitation of a university there. I first heard about the performance at the meeting of gallery members last week when Vernita announced: “I’m looking for a wedding dress. I’ll probably do bad things to it.”

Here’s how she described the project on her website:

I’m going to Homburg, Germany where David Rodgers & I are performing at the end of August for the Sommerakadamie of Kunst in Schloss Homburg, which is an annual art institute and creative gathering in the small town of Homburg-am-Main, in Bavaria, where Rodgers has been participating and performing since 2008. It’s called The Trail of Sighs and Whispers, a performance inspired by the ritual of marriage and the age-old tradition of “walking down the aisle”. In a twisted tale told through Butoh movement, costume and voice, I, The Bride, will take aim at this ritual of culture and seek to shed light on “The Wedding” and the difficulty of wedding the complex paths of two lives in the world of the 21st Century. Utilizing studies of Japanese Butoh, which I have practiced for over a decade, I will use masks and movement to create a work with feminist overtones. In this work, I will be using the streets and main plaza of Homburg as my stage, traveling by foot and bringing the audience to the entrance of the Church of St. Burkardus, where I will be joined by Rodgers as I finish my quest and he begins his. Our performances will be interrelated and collaborative, but conducted as individual performances. They will take place on Saturday, August 25, 2012, at 8 PM.”

Rodgers’ performance is called The Music of the Spheres. It dramatizes an imaginary encounter between 17th century astronomer Johannes Kepler and remarkable astronomical events of 2012, which he was able to predict mathematically in the 1600’s. The performance will explore how he reacts to finding himself 400 years in the future and learns to communicate his vital scientific discoveries to the people of the computer age. In this theatrical spoken-word performance, staged in the courtyard of the castle, Rodgers will work with local musician David Hartmann, who makes and plays all of his own unconventional musical instruments, providing the live soundtrack music to accompany Kepler’s journey through a new world.

Over lunch, on the day we put up the new juried show at Viridian, Vernita went into a little more detail on the spirit of this new work. “I’ll probably do some bizarre things along the way. I’m examining and confronting the underside of femininity,” she said. “All the things women do to make them who they are. I’m also exploring the impossibility of welding two lives together in this culture.”

She is preparing a Kickstarter project to raise money to cover the airfare to Germany and back for her and Rodgers. Other expenses they expect to cover themselves.

July 5th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Natalie Frank, Portrait of S at Fredericks & Freiser

I got home yesterday from a busy four days in New York City. I rode my R1150R down and back, and took it over the upper level of the George Washington into the city almost every day I was there. Though it was very hot most of the time, for the most part, it was bliss, not only the ride down through the Catskills but also the feeling of being able to weave and carve an original path along any Manhattan street clogged with cars. There is no such thing as a parking problem for a motorcycle in New York City. You just back the bike between two parking spaces, or at the front of a row of them, and you’re good to go. (I did bolt a lock to the brake disk.) I learned a lot on this trip, not only about riding a thousand miles on two wheels in four days, but also about a couple artists I thought I already knew fairly well and a slew of others I didn’t know at all. I also learned some basic rules about hanging a good show from Chrissie Iles, a young curator from the Whitney Museum of American Art with a British accent I loved, who showed up on Sunday—just back from Spain—to direct us in our attempt to properly exhibit the summer show she’d jured for us at Viridian Artists.

More on that show in another post, but the most fun I had on my visit was a day I spent with John Lloyd, a Brooklyn artist who joined me for a tour through various Chelsea galleries. Our conversation about art is something I want to share, mostly because it’s what I enjoy most about visiting the city. All the talk. The conversations about art and life. He’s fun to be with, because his knowledge ranges over a number of disciplines, and he touched on only a couple. John and I were comparing work histories and we followed similar paths, in terms of our art. In college, we both came to the conclusion that we needed to do something other than make art to pay bills, and I didn’t want to teach. Mostly, I wanted to paint without anyone else meddling with my head. I wanted to do what came naturally to me, not mold myself into a “career” based on what work was being done successfully at the time. John said, “I never did the bohemian thing the way our friend Lauren is doing it. I wanted an income so I learned computers and went to work at the stock exchange.” That’s more or less what I did as well: I worked two years as a staff associate for the United Way, as a way of making rent money, and then went back to grad school for an English degree, but again decided I didn’t want to teach in departments where people had to name-check Derrida while doing some savage deconstruction of Little Women or The Great Gatsby. So I got a second master’s in communications and became a reporter. I kept painting, and now it’s finally becoming more central to who I am. I do not miss the bohemian stage of being poor and struggling at all. When I’ve stayed with younger friends in Brooklyn, sleeping on an air mattress, it isn’t for the romance of faux poverty: it’s a free way to stage my visits into Manhattan, that’s all. I’m not trying to live out my twenties again in some way I missed in the past. If I had friends in a $3 million house in Brooklyn More

July 3rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, by Sargent

I’ve started another candy jar painting, part of a series I’ve been doing for several years now, off and on. This one’s a quarter the size of my usual work with these jars, which are a little over four feet by four feet. A while back, a friend at Viridian Artists, Bob Mielenhausen, suggested I try some of these in this smaller format, only two feet square, and so that’s what I’m doing, as a test, more or less. I’m also working on wood panel rather than on canvas or linen, as well as using a higher-quality paint—and I’m loving the changes—they’re teaching me a number of things about technique, but that isn’t what’s on my mind. What strikes me again and again about this series of candy jars, regardless of the materials I use, is how the results keeping reminding me of Renaissance painting. Feel free to say, Really, is that all? You and Michelangelo on the same page now? Lonely bloggers are allowed to make comparisons like this. It’s one of the perks of isolation. But that isn’t what I’m saying. I’ve never wanted to paint the way anyone did during the Renaissance—OK, that’s not true, because I’d give almost anything to paint nearly anything Bruegel painted, but I mean I’ve never attempted to adopt any methods or conventions from the Renaissance. I’ve never had the urge to paint one of Piero Della Francesca’s scenes. So I’m not entirely sure why the way I render a little oblong bit of translucent sugar reminds me of a Biblical scene from centuries ago. (It’s a coincidence that I’ve recently been reading about Italian painting from the 12th through the 16th centuries—and not because of any conscious connection between my intentions and what motivated painting during the Renaissance, but simply because I want to get into Vasari’s head, as a critic and historian.) Last year, this same similarity occurred to me. I remember looking at a previous candy jar I’d done, one that I exhibited at the last Halpert Biennial, and I thought that the loose way I’d painted some of the candy reminded me of Michelangelo. I know it sounds ludicrous to say this, but it was purely formal: the quality of the color reminded me of what the figures were wearing on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and there were other connections: the clarity of line I can get with these paintings, and also for some reason the organic curves of these oval objects often remind me of parts of the human body—a length of someone’s arm, or a shoulder. More