February 27th, 2025 by dave dorsey

Natura Morta, Giorgio Morandi, 1943, detail

Giorgio Morandi is a painter who, maybe more than any other, requires you to pass F. Scott Fitzgerald’s test for having a first-rate intelligence: the ability to hold two opposing points of view in mind at the same time without having to reconcile them. Someone not versed in art history might dismiss the charm of Morandi’s elementary style as an affectation. He is both very good and his late work also looks easily achieved. He embraces the paradox that being a 20th century artist often means having a beginner’s mind and, well, making what looks like a beginner’s marks. On the other hand, he understood how to make paintings that stood out because of what they didn’t do: he was a perceptual minimalist. He flirted with Cubism and Futurism and the Metaphysical School of De Chirico, but eventually he chose a way to paint where what he shows you almost isn’t visible. (Remember that band in the Pynchon story that thought all the notes rather than playing them?) He was a sort of monkish recluse, a J.D. Salinger of visual art, painting in his home, never marrying, living in a household he shared with three unmarried sisters. His isolation has the aura of a folk tale. Yet in his photographs he looks astute, stylish in his Bauhaus eyeglasses, with his handsome Italian visage. He was no naif. The two opposing points of view in Morandi’s case would be: a) this painting really is a pleasure to look at; b) this painting doesn’t appear to be showing me much at all. It’s sort of the definition of minimalism. Yet some minimalism looks even more minimal than the rest.

More than a decade ago, when she was working the desk at Viridian Artists, Lauren Purje introduced me to Simon Cerigo, an art consultant and collector who visited regularly. He told me he attended every gallery opening in Manhattan. I didn’t doubt it. He looked the part: intense, serious, a little disheveled from staying so assiduously informed. I enjoyed his company. He was unpretentious, laconic, and smart. In one conversation, he mentioned knowing Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore. A lot of doors were open to Simon. He died young, at the age of 60, not long after we met, but during one of our random encounters he confided his recipe for art stardom, condensed to its simplest form. He wasn’t endorsing it, just passing it along as an observer of the scene. It went like this. First, you get your MFA. Learn everything a school can teach you. And then forget all of it and paint as if there were no rules. This, as he understood it, was the path that led to a career like Elizabeth Peyton’s. Back then, she was selling awkward, quickly-executed portraits of rock celebrities and others. It’s also a way to describe the impulses that gave birth to Modernism itself: learn how to do it the academic way and discard it and paint like a beast!

I’ve never forgotten Simon’s recipe. Amid all the self-conscious spectacle of much contemporary art and the calculated look-at-me Instagram gambits artists cook up, Simon’s intrigue was: learn everything you can and then forget it. What was implied in this ostensible path to glory MORE

February 21st, 2025 by dave dorsey

Daniel Sprick

Visitors to the L.A. Art Show will be in luck: they’ll get a rare glimpse of Daniel Sprick’s work, who has been included this year in the lineup of painters at Arcadia Contemporary’s central booth. Arcadia usually serves more or less as the LA Art Show’s tent pole. It’s nearly unavoidable as you walk in. You can spend time in the booth and then really can’t escape it until you head back to the parking lot. You move out in various directions only to walk past Arcadia’s sprawling space on your way to see work on the other side of the building. Sprick’s paintings are a rare treat. He had an astonishing, definitive solo show at Arcadia a couple decades ago where he painted various scenes from his studio. Objects for him are arranged carefully to create a formal composition but his skeletons and tools and tightly bound fabrics find their place in your field of view so haphazardly that the scene looks as if he’d discovered it rather than set it up. The light in one of his paintings is liquid, offering just enough illumination to offer precision, but rarely bright. His handling of paint in that show was flawless and tactile, bringing to mind the gifts of Gerhard Richter and even Velasquez. His skills haven’t faded. He’s able to make random arrangements of tools and objects in a studio look as if they are perfectly situated to convey exactly the quality of light falling on them through his studio windows.

John Brosio

There are dozens of other opportunities for awe at the Arcadia booth this year. Once again, guy-in-charge Steven Diamant is exhibiting an amazing quantity of masterful painting, all of it idiosyncratic, some of it quite strange and dark (stopping just this side of morbid here and there), some just the opposite, bright and affirmative and flush with vitality. Much of the work offers hyperrealistic depictions of time-shifted dreams from an indeterminate past, a transposition of slightly antiquarian styles or objects into the present, a visionary esthetic that has found a welcoming dwelling at Arcadia. John Brosio continues to depict low-rent locals or storefronts unwittingly providing a foreground for apocalyptic landscapes behind them. Occasionally he cashes in on the potential for amusing ironies in these hermetic dramas.

Adam McGalliard

You feel you are gazing into a snow globe where a couple shakes might stir up a few tornados rather than snow. Adam McGalliard, in painting after painting, juxtaposes splendidly lush bucolic scenes with a figure clothed in an antique-looking spacesuit. Like a pre-Raphaelite Ophelia, his drowned subject, young and beautiful, floats, nearly submerged, in a blooming marsh, face up, eyes closed behind her helmet’s bubble of glass. Michael Chapman gives us strangely aimless, remote-feeling urban scenes, lonely even when populated with human figures, the way Hopper’s always felt. Now and then, an Albers square appears or a lost circus bear makes a cameo appearance, as if each of these paintings were a John Irving novel.

Michael Chapman

ch

Stephen Mackey offers more of his unsettlingly Gothic visions of fey children and skull-or-animal headed chimeras, not threatening enough to be visualizations of night terrors but weirdly almost soothing, the way I would imagine a vampire’s request to come inside for a bit.

Other painters take postmodern liberties with similar time-shifting but without the surreal fevered reveries. Patrick Kramer’s images offer a postmodern reprise for historic artwork: Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa, brilliantly copied, but on further study it’s incomplete and falling apart:

Mary Jane Ansell

in the tromp l’oeil reproduction it becomes clear that Gericault’s painting is peeling away like wallpaper from a surface behind it. In paintings with an exquisitely finished surface where mark-making has been completely effaced, Mary Jane Ansell presents, in different settings, a young woman in a suggested narrative, sometimes as a sort of Joan of Arc with hints of a vast army behind her. The contrast between the contemporary girl-next-door beauty and the antiquarian narrative and costume intensifies the impact of both the portrait and the setting. Jong-Jae Kim offers a second nod to Edward Hopper in the show:

YongJae Kim

a reprise of Early Sunday Morning, a small town’s depopulated street with its long row of windows and doors, a sort of Hopper 2.0. Stephen Foxsubmits his astonishing drive-in movies: still images from easily recognizable films like giant nightlights glowing under dark skies in surviving drive-ins, a few cars assembled, sometimes a little lightning in the distance beyond the screen, a venue in many places still stubbornly drawing viewers willing to burn the gas needed to attend the showings. Alberto Ortega is well represented with multiple versions of his twilight and night scenes painted from dioramas he constructs himself, often with accessories—figures, buildings—from supplies for model railroad hobbyists. As with Chapman, Ortega’s scenes include

Alberto Ortega

the egg-shaped cars with rounded fenders from seven or eight decades ago. His appear along haunted residential streets with people who seem to be dazed by the dream he’s created, fixed with indecision or intent on half-hearted errands. Shaun Downey’s assiduously hyper-real portraits of women seem to float outside time; the styles of hair and clothing, the glamourous ook of the faces almost suggest mid-20th century starlets, surrounded by flora blooming in such profusion they seem to inhabit that botanical

Shaun Downey

medium like air or water. Downey, like many of these painters, seems to be saying yes to what he most wants to see emerge as he paints, regardless of whether or not it fits with anything anyone else is doing in the art world. This ideosyncratic choice applies to many of the painters at Arcadia. It’s a choice that Thiebaud made before he emerged, when he finally decided after much anxious deliberation to paint subjects others would have thought trivial or frivolous; the same choice Inka Essenhigh made before she became as one of the most original painters working today.

The show is also replete with portraiture, figures, and still lifes each suggesting a world firmly recognizable but no less oneiric, as Bachelard would have put it. Floral paintings are a difficult feat, and many representational painters don’t have the patience for it. All of the floral work is impressive in this booth, but two examples are exceptional: Daniel Bilodeau’s peonies manage to convey exactly the texture and color of new peonies as they are just starting to bloom. The tissue-thin petals in his work are immense achievements of sustained observation and handling of his materials. His enlarged images of flowers are really cornucopias, celebrations of nature’s abundance, but they are constructed with a remarkable acts of sustained, assiduous attention. Jonquils and narcissus are extremely hard to paint effectively as well; the required variations in white and yellow don’t yield readily to a quick easy shortcuts. Jane Beharrell captures them in a simple still life that will remind everyone of the season about to return in a couple months.

Anne-Christine Roda

Mary Sauer, Miriam Hoffman, and Kesja Tabazcuk offer quasi-traditional portraiture but in each case the painter’s consummate skill and originality of vision make the sitter’s identity nearly inconsequential: the painting itself holds your attention because of the life it conveys. Each of the three artists handle paint quite differently but with skills so advanced the work looks as if it revels not just in the painter’s abilities but in the quality of the paint on the surface. Anne-Christine Roda’s image of a young woman wrapped in a white blanket could pass for a lost, newly discovered Zurburan, the work is so refined and so old-school Spanish–without looking at all dated. Dana Saltzman’s image of a bowl filled with water and a cloth, sitting on uneven ceramic tile bearing a faint blue pattern, is equal to anything Richard Maury has done in still life. Sung Eun Kim’s twilight city streets evoke the gritty romance and beauty of an American city’s ceaseless, impersonal energy, and Caren Wynne-Burke’s architectural facades with sky compete respectably with Christopher Burke’s rooflines.

The fair runs through Feb. 23, plenty of time to check it out this weekend. You can view all the Arcadia work in this online catalog: Arcadia, LA Art Show.

February 15th, 2025 by dave dorsey

Jimmie, archival digital print

I showed up late for Michele Ashlee-Meade’s solo show, too late to hear her talk at SUNY/Finger Lakes Community College—only a couple stragglers were still there studying her photography. Yet the room was a beehive of silent conversation. A dozen voices spoke from the walls around us, both in the photographs, and in the brief oral histories transcribed beside them. Letters to Myself, Portraits of Adversity is a marvelous assembly of the photographer’s friends: homeless, ill, struggling with addiction, celebrating modest personal victories, remembering things that made them cry, and yet everywhere looking as if they were reveling in life.

Ana, detail

Her photographs exude emotional strength, self-awareness, wit and in a few cases startling glamour. She asked each of her subjects to write or talk briefly about themselves, mounting their statements—sometimes in their own hand—alongside each portrait at Williams-Insalaco Gallery 34.

She’s an engaging talker herself, articulate about what she’s doing with her photography, but what comes through most clearly is her deep appreciation for and delight in nearly anyone she meets. It’s what charges her work with life: this ability to see someone else from the inside out. She documents the lives of men and women she meets in all phases of her day, including her work at St. Joseph’s House of Hospitality, where she helps care for the homeless. As with Avedon’s portraiture, much of her work captures a spontaneous moment, while other portraits are posed with

Truth

care against backdrops that amplify or contrast with the subject’s character. A beautiful woman in an elegant dress bares one shoulder in front of an abandoned lot strewn with detritus. A bisexual, married woman who wanted to remain unidentifiable is covered from head to foot in black drapery, wearing eyeglasses outside her costume like Cousin Itt hiding behind a body-suit of hair. She’s posed in a narrow alley between brick walls with a fire escape behind her offering a retreat that looks more like a trap. Homeless since 2007 and sixty days sober, a smiling man lofts a half-finished pop bottle like a trophy beneath bright, white clouds.

What comes through in the faces and the personal, biographical accounts she excerpts from each subject is how much they not only have suffered adversity, but have overcome it and drawn energy from the strength it trained in them. Her images are rich with shadow—she luxuriates in value and focal contrasts that highlight the detail that give immediacy and history to her faces, yet the photographs are anything but dark. After having read the terse personal accounts of these people and recognized even more in their faces, you want to keep looking, and, most of all, to hear them keep talking.

January 29th, 2025 by dave dorsey

1

It has to be nearly impossible to sound pretentious when writing about candy, but I can probably find a way. My intent in painting images of gumballs and taffy and Chiclets leaves little room for grandiosity: I love these sugar delivery systems for their utter insignificance. But talking about any sort of painting since the advent of modernism is difficult to do without sounding like a self-important smarty pants. So, if I do, I ask in advance for your pardon (pardons are getting handed out left and right these days). Sounding obscure and difficult is just a part of the predicament of visual art since the late 19th century, as Tom Wolfe suggested in The Painted Word: we feel the need to philosophize about it. I like painting taffy for a number of simple reasons, mostly because I can lord it over a piece of taffy like a sculptor working with a tiny chunk of modeling clay in a translucent wrap, both of which—taffy and waxed paper—can be arbitrarily shaped and positioned. It’s raw material for an exploration of color, value, form, light, space, volume and line. Its interest is purely formal and visual and sensory for me. (More on this later, because it’s not as hedonistic as it sounds.) By sensory I don’t mean the memory of sugar and flavor. I rarely eat candy. My relationship with candy is that I buy it and abuse it by neglecting it for a time until I reshape and/or rewrap it and then keep adjusting until it looks fit to be photographed. (Often though it’s what I can’t change that determines the character of the image.) I have let hundreds of pieces of taffy sit in bags in my studio for years, each piece deliquescing though its waxed paper wrap. Sometimes I dig into these sticky grab bags for a few pieces I’ll need for a new painting before it completely decomposes. As salt-water taffy ages, it actually extrudes itself into little lobes and globes of hardening sugar water, apparently oozing through invisible pores in the paper. It ends up looking afflicted with deformities. And, after a few years, even when stored in the freezer, some flavors become soft as burnt marshmallow. If you unwrap a piece, it just sticks to the paper and stretches into tendrils like newly chewed gum or Neo’s mouth in The Matrix.

This mutability actually points to the other reason I like taffy. When it’s new, it’s like hardened Play-Dough or modeling clay, with sharp little interesting crags or dents and creases you can adjust just slightly. When it’s new, you can unwrap it cleanly to rewrap it with a square of fresh waxed paper from the supermarket for an entirely new element of drapery that can be modified to look like a Futurist sculpture. You can control much of what will present itself to the viewer: the candy offers itself as raw material to be molded, twisted, pressed, plumped, balanced, squashed and generally manhandled into an image that somehow looks unified when depicted in paint. But I can modify things only up to a certain point. Too much reworking and some element of simplicity gets lost and it becomes shapeless.

All of this came to mind after I’d written recently about William Keyser’s sculpture where he combines found objects he pairs with other components he fabricates. Someone categorized my paintings as planned. Actually, the only planning is in buying the taffy: after that I take what I find and reshape parts of it until I realize I have something that works. It isn’t working from a plan, but working in the dark toward something that becomes recognizable as an image I want to paint while I struggle to come up with the source image. It later occurred to me that Keyser is a creative cousin to another favorite artist of mine, Susie MacMurray, whom I interviewed at Danese Corey in Chelsea before it closed: in their work, they both transform overlooked or common things to find a form that has resonance for them. Bill innovates by pairing what he finds with what he invents. His three-dimensional bricolage triggers various associations. It MORE

December 11th, 2024 by dave dorsey

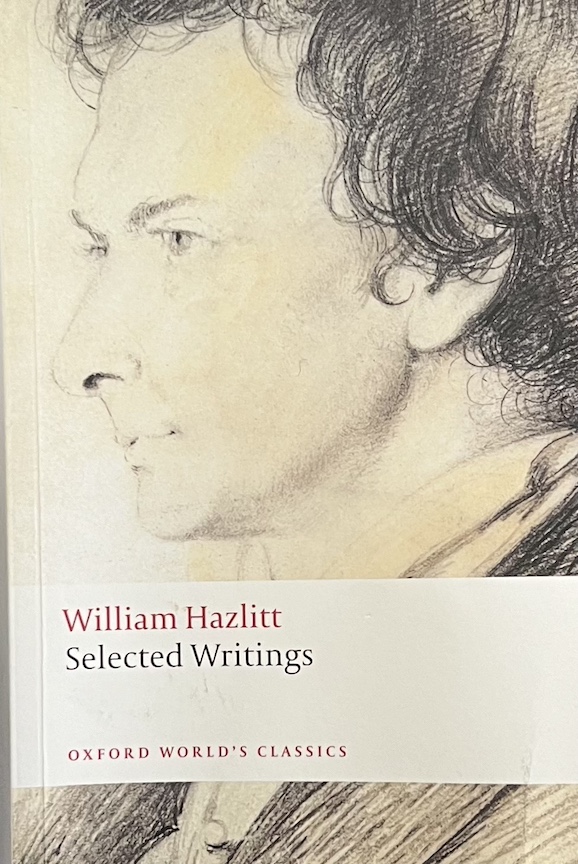

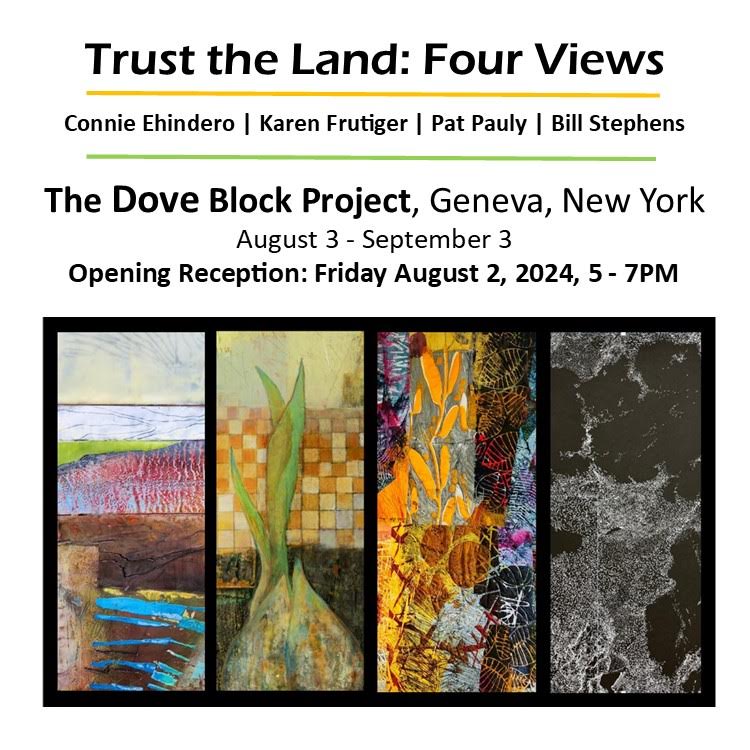

Jean and Bill Stephens, courtesy RIT

There are a few days left to see Continuum, the current exhibit of new work by Bill and Jean Stephens. They are both long-time art educators who met and fell in love at Rochester Institute of Technology fifty years ago in the printmaking studio on a floor above the one where their work now hangs.

The work is arranged almost symmetrically, in an alcove open to the main exhibition space filled with politically motivated fiber art. (Some of the adjacent fiber work is quite good, extremely well crafted and almost childishly subversive given the soft, amiable quality of the medium.) It’s an apt curation, each exhibition contributing to the spirit of the other. Jean’s subtle and spiritually suggestive collages alternate on the walls with Bill’s abstract paintings in acrylic ink and gel pen. Husband and wife, this creative team has been improvising new work for decades, responding to first marks and finding a way forward toward a sense of completion in whatever medium they choose. In his dark paintings, the imagery comes forward from a black ground of permanent ink he lays down over the entire support. He removes the ink with an alcohol solution and then makes marks with fine-point white gel pens. Bill’s soul resides in the drawing, the almost microscopic-looking marks—thousands of them—that move in waves across the surface of each painting. In others he erodes the blackness into egg-shaped modules, like jostling cells, that form designs he doesn’t anticipate but discovers as he works.

Jean creates gelli prints building new textures of color with a brayer, and then she assembles portions these prints as a collage, along with found objects such as postage stamps or newsprint or columns of text or shreds of maps. In many of the pieces on view, she improvises her own imagined ancient script, which looks Middle Eastern. It’s quite persuasive, and on these faux Arabian lines she creates a sense of flow and assurance, like a master calligrapher’s brushwork. Jean told me she isn’t saying anything in particular in this automatic writing, simply channeling script in a tongue not yet defined. The work is playful and associative and brightly affirmative, dreamlike—the words sweet and spot serve as bookends for one images. It’s all essentially as improvised as her husband’s paintings. Her collages often look like disassembled and rearranged modernist mandalas, with north south east and west wings.

As a whole the entire show is introverted—in the sense, say, that Paul Klee’s paintings were introverted—and very understated. It’s quiet the way someone who would like to be heard speaks so softly you pay closer attention.

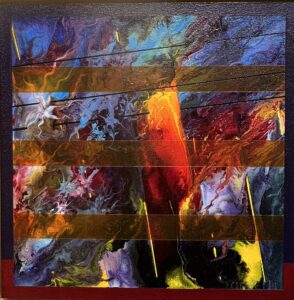

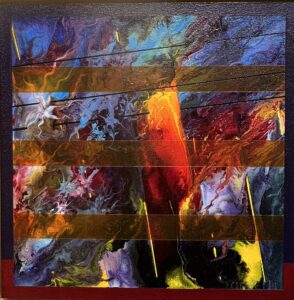

Flash Instant, acrylic Bill Santelli

I gathered with some other artist friends to talk about the show and our life as artists: Bill Stephens, Bill Santelli, Barron Naegel, and William Keyser. Stephens talked about how he works, but his process is instinctive and meditative; he doesn’t indulge in the kind of art-statement doubletalk that so many artists use to inject a bit of fuel into a career. We sat in a circle at one of the tables in the School of Art and Design in Booth Hall.

Stephens: I work with permanent acrylic ink, Caran D’ache crayon and white gel pen. I put down the black background and then remove it with alcohol wipes.The whole painting is done in black acrylic ink and I go in with 70 percent alcohol wipes and remove the ink to create shapes. The ovals are made using my finger. I pick up the texture of the canvas underneath. Then go back in with a fine point pen. White marker on top of the black. I had a young woman recently ask me, Mr. Stephens, when do you know when a painting is done? When I die, I’ll let you know that it’s done.

Santelli: How do you feel about where you are in your work?

Stephens: Good. I’m always experimenting. That’s all I’ve ever done. It’s coming together.

He keeps laughing after he says this, suggesting that his work MORE

November 22nd, 2024 by dave dorsey

Flash Instant, acrylic on canvas on aluminum panel

When Bill Santelli was seven years old, in 1960, he discovered Jackson Pollock in Life magazine, and it changed his life. He walked up to his mother and said, “I’m going to France to become an artist.” On his way to France, he didn’t make it past his mother, nor did he get there to study art when he was older, though he flew to Paris during his honeymoon with his wife partly on a mission to see Pollock’s The Deep at the Pompidou Center. When he came of age, he went to live and work in L.A.

During his talk for his new solo exhibition’s opening at SUNY/Finger Lakes Community College, he said, “Along the way, it was necessary to earn money to keep painting, and so began shadow-careers in education and arts-related businesses. I forged an independent lifestyle that way. I’ve held positions as a high school art teacher; archival picture framer; manager of the largest antique print gallery on the west coast in LA; sales person and book buyer for an art supply company.” Eventually, in 1991, he was able to make a living as a painter without any side hustles partly by learning to market his work himself in an era when it was easier to work with agents to promote work. “In art, survival is success.”

He’s done far more than survive. As Barron Naegel, the gallery’s director, pointed out in his introduction to Santelli’s talk, he has combined his MORE

November 17th, 2024 by dave dorsey

Alberto Ortega, Community Watch, oil on panel

Some Arcadia Contemporary painters produce work so rapidly, I wonder how many hours of sleep they’re able to get during an average year. It feels like Alberto Ortega’s last solo show at Arcadia Contemporary was a few months ago. You can see a tranche of his new paintings at Arcadia until Dec. 1. His visions feel paradoxically like precognitions of a past (circa 40s, 50s, maybe early 60s) we are destined to relive alone together. They are achingly haunting. They have the quality Bachelard called “oneiric” in The Poetics of Space, halfway between waking and sleep. He builds original dioramas and then stages twilight or night scenes that feel like intimate, antique precursors of Gregory Crewdon’s cinematic scenarios and then paints from views of these constructions. I’m eager to see the work on a visit to the city in a couple weeks.

November 11th, 2024 by dave dorsey

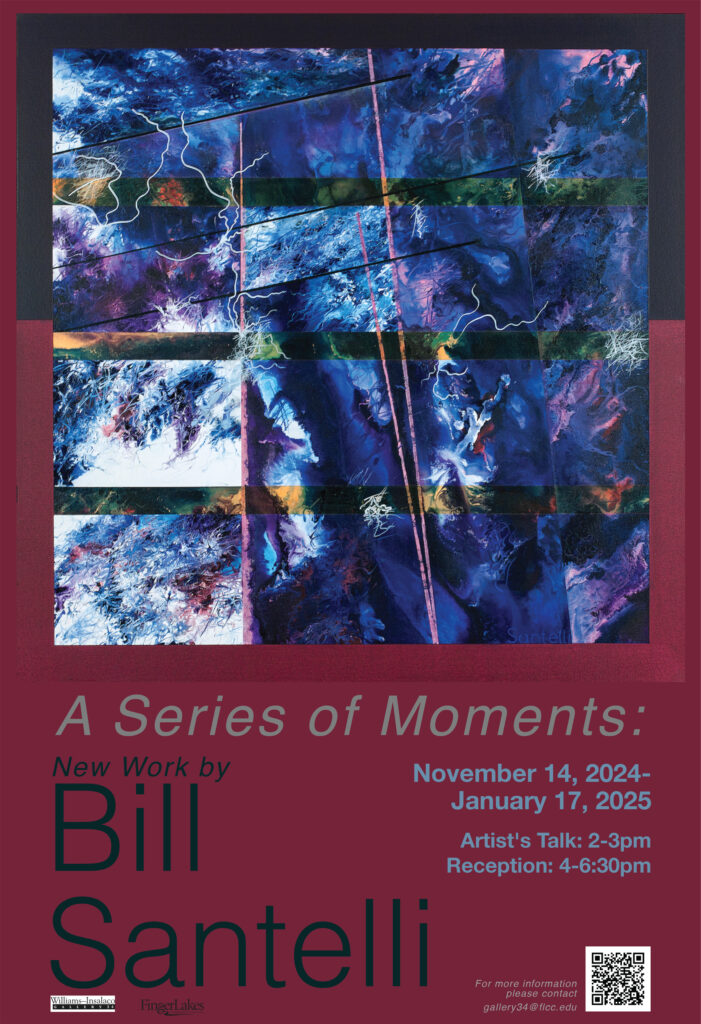

A show of new work from Bill Santelli opens next week at Gallery 34, Finger Lakes Community College. I’m eager to see the actual work after seeing his posts on Instagram the past few years. Santelli has struggled with health issues and chronic pain that haven’t seemed to hinder his output except to reduce the amount of time he spends each day in the studio. The reception and artist’s talk will be on Nov. 14.

November 11th, 2024 by dave dorsey

Going to schedule a side trip to talk with Matt about his new show in a couple week, after a visit to NYC. I’m interested in how Klos evolved from the Lopez Garcia style of realism he mastered in college to his approach now as a perceptual painter and also how he defines this school of painters. I had a quick conversation with him recently about how Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts is shutting down its degree program and he agreed that there may be a sea change coming in higher education, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I hope to pass along his thoughts here after I see him in person.

November 8th, 2024 by dave dorsey

Eager to see new work from these two innovators who are continuously experimenting with materials and methods.

September 13th, 2024 by dave dorsey

Wellesley Island Beach Triptych, detail.

1

It’s hard to imagine a less picturesque subject than the Inner Loop, a channel of traffic that circles and threads its way through downtown Rochester. It might be an interesting route for an F1 race at some point, but it wouldn’t strike most painters as a promising place to search for beauty. In Common Ground, an astutely curated show of Jim Mott’s paintings and Andy Smith’s photographs at Lumiere Photo, Mott’s views of the Loop (originally exhibited at RoCo in 2011) serve as an anchor for understanding what he’s up to. Paired with his paintings of the High Falls and the Rochester skyline, these larger paintings, often with wide, panoramic dimensions, offer a wonderful path into Mott’s work in general. The exhibition is more comprehensive than it looks at first glance, with fifty paintings by Mott on view. It essentially serves as a retrospective of his work from the past 20 years.

In Downtown River View, Mott uses office buildings, along with a bridge over the Genesee River, as a way of structuring the image geometrically. At the same time, he relieves the rigor of that grid with the organic shapes of trees along the river banks and the Genesee tumbling across the bottom of the painting. Throughout the image, Mott simplifies what’s being depicted and minimizes his detail, in a sense making as few marks as possible to capture the reflected light that gently illuminates most of the shadowed scene while striking the higher buildings, bringing them into bright relief against a pale blue sky. Mott’s strategy is to leave most of what he sees ill-defined.

Avoiding definition is his way of life in an even broader sense: he doesn’t try to define what he’s doing as a painter. His approach is apophatic: eliminate thinking to make discovery possible. I’ve heard him say, only part joking, many times, “I don’t know what I’m doing.” Each time he begins a painting, he relearns how to capture the scene and his approach is never a repeatable series of technical moves; it’s always an improvisation. Mott believes that pushing toward tighter definition MORE

August 17th, 2024 by dave dorsey

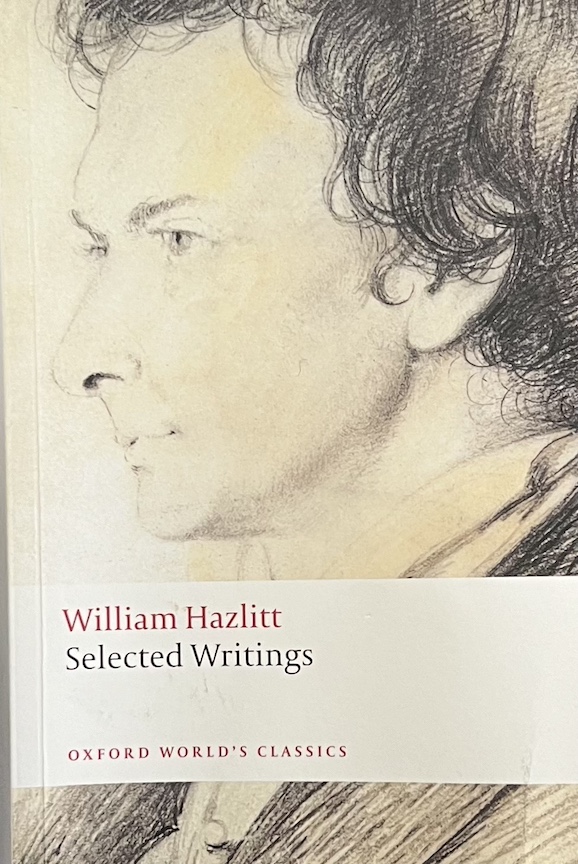

“Hmmmm.” At the door he turns and fixes you with a serious look. “Read Hazlitt,” he says. “That’s my advice. Read Hazlitt and write before breakfast every day.” –Bright Lights, Big City

Sounding much like a precursor to Dave Hickey, a portrait of William Hazlitt, from the Introduction by Jon Cook to William Hazlitt, Selected Writings:

Hazlitt’s argument about the arts can be understood . . . as a metaphor for freedom. As polemic, the argument fueled his assault on the British art establishment of the day. Hazlitt was deeply suspicious of Joshua Reynolds’s attempts to improve the education of artists and their public through the institution of the Royal Academy. Where Reynolds thought to dignify the artist by turning art into a profession, Hazlitt regarded professionalism and genius as antithetical. The Royal Academy provided a dignified cover story for turning art into a species of commodity production. It was ‘a mercantile body … consisting chiefly of manufacturers of portraits who pander to the personal vanity and ignorance of their sitters’.

Far from improving art and educating its public, the Royal Academy hastened a process of decline which Hazlitt thought was already inevitable. Hazlitt’s polemic against Reynolds and the Academy is suffused by a melancholy resistance to the idea that art can be improved by becoming subject to an educational regime. Hazlitt makes the history of art speak against this meliorism. One radical implication of this view of history, and one which Hazlitt occasionally voices, is that there can be no such thing as a beneficial tradition in the arts. The arts are strongest at an early stage of their history because their expressiveness is not constrained by the accumulation of precedent. Artists were not obliged to be always looking over their shoulders to see what others had done. They could be ‘original’ in one of Hazlitt’s primary senses, by representing in their art some particular aspect of nature which had been uniquely disclosed to them. By contrast, the opportunities for originality in modern conditions are limited not only by the accumulation of preceding work which stands between the artist and an original representation of nature, but also by the need to assert the distinction of any work against the claims of contemporary rivals; hence, the restrictive egotism which Hazlitt discerned in a number of his contemporaries, an egotism necessary for their survival in a crowded market.

He attempts to return our experience of art to a moment which Susan Sontag has described as ‘before all theory, when art knew no need to justify itself, when one did not ask of a work of art what it said because one knew (or thought one knew) what it did.” The attempt is essentially ironic, and self-defeating because in writing about art the critic returns it to the very realm of discourse from which he wants to defend it. Running alongside this is another kind of fantasy: art, in Hazlitt’s writing, both in its creation and its reception, stands for the possibility of an unprecedented and unpredictable event. The career of Napoleon is the political correlative for Hazlitt’s sense of this kind of freedom and power in art, and stands as a reminder of how much artistic genius meant to him as a form of ambition realized without the privilege of noble birth or professional status.

Hazlitt’s beliefs about art illustrate his ambivalence towards the legacy of the eighteenth-century enlightenment, which, in his Life of Napoleon, had figured as the cause of the French Revolution. If reason, and the circulation of ideas through the printing press, promoted new kinds of freedom, they also were in the service of new forms of centralization and standardization which seemed to diminish the possibilities of dramatic expression and debate.

Hazlitt’s value as a writer may well be in the thoroughness with which he registers such ambivalences and his corresponding refusal of the protection of intellectual systems or political establishments. As a dramatic thinker he can be volatile and unpredictable, a writer who resists critical framing. But this is at one with Hazlitt’s sustained commitment to the values of freedom and dissent, something which sets him apart from a subsequent English tradition of critical thought devoted to dreams of social stability and obedience. His writing is open to the reader’s agreement or dissent; it is not in pursuit of disciples. His tone is democratic and secular; even now, this can make him seem a moving, and even exemplary, figure.

August 15th, 2024 by dave dorsey

Snowmelt, oil on linen, 24″ x 24″

All art constantly aspires to the condition of music. –Walter Pater

This year I received an invitation to show my work at either of two exhibitions in Venice, Italy, and another invitation to exhibit in Spain. There’s no prestige associated with these shows, just an opportunity to get a little visibility, but I’m not going to bite. It’s quite an undertaking to ship work to Europe; I know because of the struggles occasioned by sending a small still life to Prague last year. The theme of the Italian exhibition, though, Consciousness and Visions, prompted this post. I’m mostly a still life artist, so it required some insight for the curator of the show to recognize how I might fit into those shows, but I suspect their invitations cut a wide swath and one could argue that any painting is an example of a vision but no one would need to argue that a great painting aims to arrest and alter the viewer’s immediate awareness of the world.

More than a decade ago, when I was showing work in Chelsea, I met Jane Talcott, a painter in Brooklyn. She immediately understood what I was doing, generally working in two different modes: “The still life work is about the outside world; the candy paintings are about the inner world.” The distinction isn’t hard and fast or exhaustive nor all that intentional, but she was mostly right: all of the paintings attempt to evoke states of mind, meditative experiences of a world otherwise incommunicable. Yet my more traditional still lifes do this, if they do it at all, by offering a glimpse of what one normally sees in the external world, while the candy paintings offer isolated, enlarged, straightforwardly realistic renderings of what’s there, but by isolating the subject and eliminating any surrounding context, and radically changing the scale of what’s seen, the effect becomes far more abstract. The impetus for the candy paintings has more in common with abstraction than traditional representation. I don’t improvise on what I see. I create the image in large part, before I ever pick up a paintbrush, in the physical act of arranging candy in a jar or when I wrap two pieces of taffy and try to find a way to get the visual elements to work together, given the shapes of the waxed paper, in some kind of unity of line, form, shape, color and light. When I look at two chunks of salt water taffy, sitting on the reflection of the lower piece, I think of Rothko. Three areas of color, stacked, uniformly and repetitively configured, but in my case with variations in line and hue and tone, in the sculpting of the wax paper, to express very different moods, or different experiences of a particular place and time, or simply inner states of awareness. Candy is what’s visible, but candy isn’t the subject matter, or rather it isn’t what the painting is “about” any more than a long jam built around a song about Casey Jones is about rail transportation or being cautious after an application of cocaine to one’s work day.

Instrumental music is the best metaphor for what I’m trying to do with candy paintings. It isn’t so much a metaphor as an equation. It’s hard for many people to see painting this way, but with the emergence of abstraction more than a century ago, it’s impossible to miss how painting at least partially makes visible what music makes audible. The fact that each painting is structurally identical in most ways, with variations in color and line and form—inside the structure—offers a way to do what abstractionists have done for decades, to keep reworking a motif and see how a set of severe restrictions on one’s choices can yield a series of images that evoke different kinds of responses and ways of seeing. Numerous artists have explored the expressive possibilities of tightly restricting their choices in formal terms and working variations within these restrictions: Rothko, Noland, Stella, Barnett Newman, Agnes Martin, and many others. Abstraction, for these painters, evokes a musical structure where the major formal elements remain uniform but each painting creates a different response by subtle varations within those formal restrictions. This is how I want the candy paintings to work. So what’s seen, for me, isn’t the literal subject, candy, but an elusive sense of a world summoned by a composition by Erik Satie. I’ve sold ten taffy paintings since last summer, thanks to Arcadia Gallery, Oxford Gallery, Artsy, the LA Art Show, and the Greenwich Art Society. At least one collector bought a taffy painting because the literal subject matter reminded him of taffy from his childhood. I like that, but that isn’t why I paint candy. I suspect others see through and beyond the objects to what the abstract qualities of each image can convey, in its visually musical way.

The annual Five and Under group show begins this week at Arcadia Contemporary. I will have several taffy paintings on view in the exhibition.

July 19th, 2024 by dave dorsey

May 14th, 2024 by dave dorsey

Fall, oil on panel, 9″ x 12″

There is still plenty of time to see Second Sight, a final solo show of work by Ron Milewicz at Elizabeth Harris before the gallery space permanently closes. It’s another Manhattan gallery to mourn, along with OK Harris and Danese Corey and many others. One wonders how long rent can keep rising in Manhattan before a growing number of commercial spaces become permanently empty. This particular show is a treat, showing how Milewicz continues to refine his idiosyncratic, radiant vision of nature. His paintings seem almost a visualization of what the English Romantic poets and the American transcendentalists extolled: the spiritual energy inherent in nature. I’ve compared his work before to Burchfield and to a Tennessee painter, Nick Blosser, whom I discovered a couple decades ago at the Adam Baumgold Gallery. What’s distinct in Second Sight is the central importance of light: the world of nature Milewicz depicts seems not just to be intensely illuminated, but to be made of light or lit from within. This isn’t an easy feat to pull off but he does it beautifully.

In Maple Swirl he offers the viewer a single green maple against a background of the surrounding woods. Light shines through all the gaps in the leaves, and it works as a representation of a shaded woodland view. The greenery is perforated by the bright, midday sky softly piercing the tree. Yet there’s an intentional confusion of figure and ground, emphasizing the abstract alternation between white and green (the painting is almost entirely those colors), and giving the glimpses of bright light a congealed but ghostly physicality, as if they are dancing in the foreground, between the viewer and the tree. He’s as interested in the quality of that light as he is in the tree he’s ostensibly painting. Here the tree reveals the light rather than the other way around.

In Not So Pink Pond, the light glows around the edges of branches and leaves, the way sunlight glows outward from around the borders of clouds. The row of slim trees reaching up to the canopy remain dark, lit from behind, but Milewicz applies great effort to rendering the varied color of the shaded trunks and the soft ovoid condensation of faint color that give volume to the leaves—the color in both foreground and in the brightly lit clearing beyond that MORE

April 6th, 2024 by dave dorsey

White and Lavendar Phlox with Michelangelo’s Infant, 1998, oil on canvas, 52″ x 52″

April 3rd, 2024 by dave dorsey

La Coiffe Bleue, oil on wood, 20 x 20

Anne-Christine Roda’s portraits, mostly of her daughter, are a must-see for anyone in New York City during these last seven days of her solo show at Arcadia Contemporary in SoHo. I was impressed with her work in the digital catalog emailed out before the show opened, but there’s little comparison between the albeit excellent photography and the presence of the work itself. In a quick visit to the gallery yesterday, I was astonished and moved by the immense discipline brought to these paintings.

They are good on every level: technical skill, the quality of the paint surface, the intensely personal and unpretentious relationship with her sitter, and the almost monastic simplicity and austerity of the information each painting conveys. The title of the show, Les Silencieuses, conveys the aura of Roda’s work: it’s all signal, no noise, and it’s a precise, narrow bandwidth of signal at that. The peak and trough of her wavelength are shaped at one extreme by the spiritual, protective quality of her care for her daughter embodied in these paintings, and the contrary sense that this young woman is on the threshold of what is inevitably a wildly unpredictable adulthood. This young woman is an icon of purity and vulnerability, her image indelible and protected by its frame, though the actual sitter, the living human being, will find nothing equivalent to that safety in the world.

To say the work is hyper-realistic is almost an understatement, but also misleading. Her inspiration comes from the Old Masters with their dark baroque backgrounds and almost somber moods: intentionally or not, Zurburan looms large here, but the finish she brings to each painting compares as well with Rembrandt and Van Dyke. Her surface has a smoother finish than much work by the Old Masters, closer to the uniform absence of brushwork one sees throughout hyper-realism, but while her edges can be distinct and precise, there’s an unaccountable softness in the light and the texture, even the skin of a leg or arm. The feel she brings to her paint handling mysteriously remains sensuous and incredibly supple, even with such little evidence of her brush: her tones are impossible to describe in some places, the shadow on the back of a hand, the color of the creases in a knuckle, seeming to effectively blend every possible hue while representing the absence of color. I would think her achievement with these paintings MORE

April 3rd, 2024 by dave dorsey

Still Life with White Eggplants and Radicchio, 2011, oil on linen, 16″ x 26″

March 31st, 2024 by dave dorsey

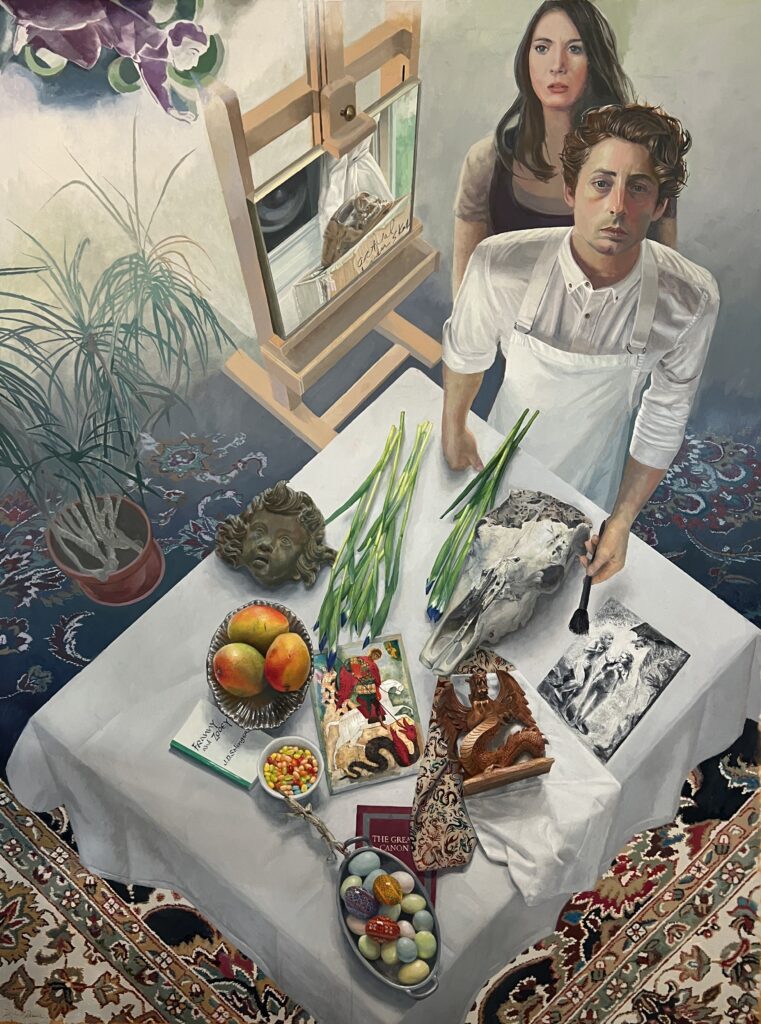

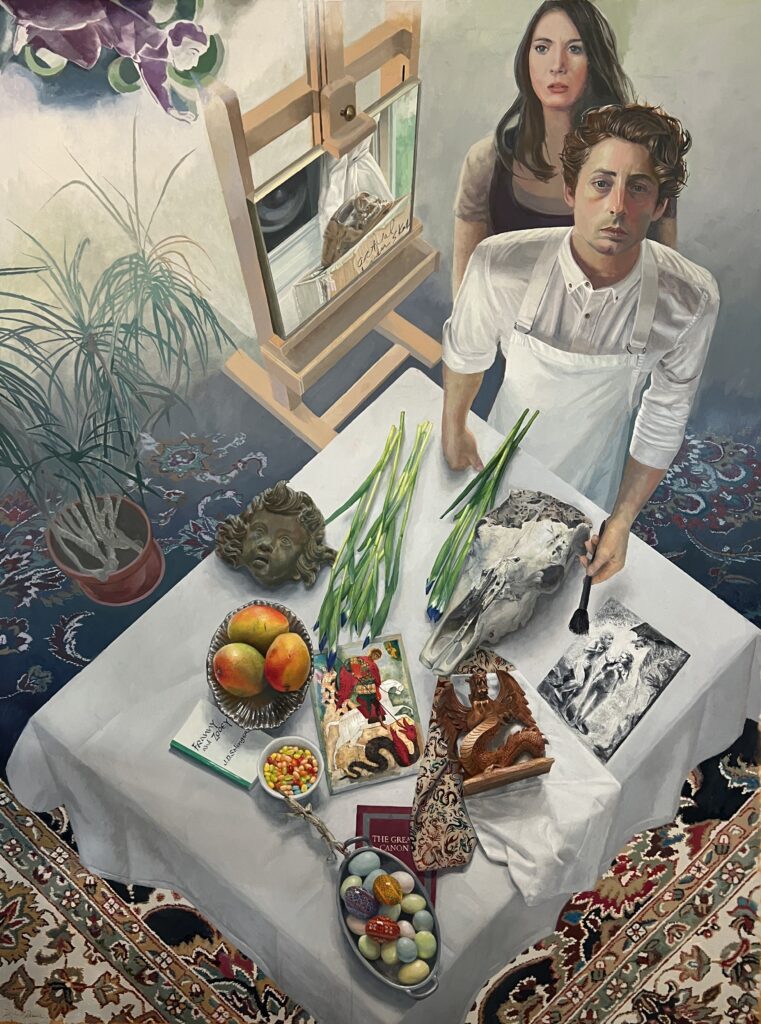

George’s Dream, oil on linen, 60″ x 80″, 2024

There are a few small things to do still, but this is essentially complete, for The Stuff of Dreams at Oxford Gallery, opening in about three weeks. I started George’s Dream in late November though I had been sketching and researching elements of it for more than a year. I was exploring the theme of St. George and the dragon from different angles, though I ended up creating the image of a dream that starts out near the bottom as one of the tabletops I’ve painted for many years and then dematerializes a bit into the dream as your eye moves to the top of the canvas. It was ironic to be working on this during my No Ideas But in Things solo show at SUNY-Finger Lakes Community College, which was a survey of work from the past fifteen years rooted in the idea that painting communicates and embodies an awareness that has little or nothing to do with the kind of thinking that recognizes narratives. This is certainly an image that suggests multiple interpretations, so it’s completely outside the scope of how I work as a painter: to try and bypass illustrated ideas. But having the occasion of the theme Jim Hall offered gave me a chance to work in this mode. I found it challenging and rewarding from start to this provisional finish, though there were two or three tedious periods along the way. It’s nearly seven feet high, so I had to buy a small scaffold at Home Depot in order to work on the upper third of the image. I found myself doing half a dozen unfamiliar things and discovering that I could, in fact, get satisfying results with some objects when I had serious doubts about my ability to depict them accurately. Many thanks to a painting by Chagall for that Cubist cherub in the upper left corner. It’s my favorite painting of his.

March 28th, 2024 by dave dorsey

Le Chemise Blanche, oil on linen, 56″ x 45.”