Book of innocence and experience

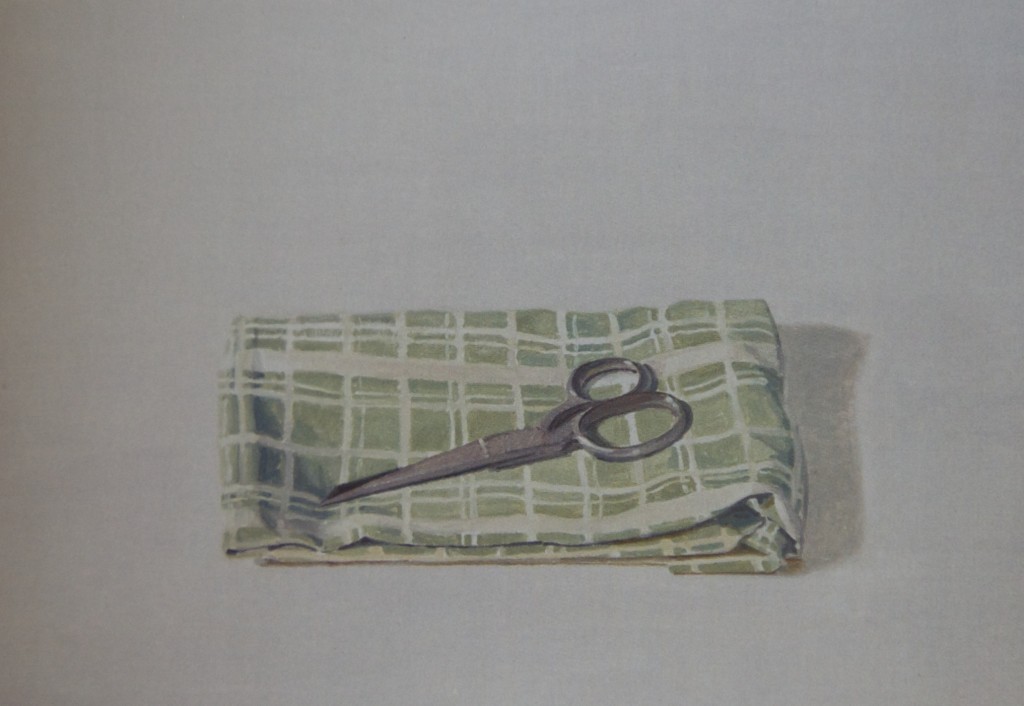

I’ve never posted two paintings from a show I’ve written about, so that alone ought to indicate how much I liked this one. One of the deepest pleasures of my visit to Chelsea two weeks ago was seeing the quietly commanding still life paintings of Ron Milewicz at Elizabeth Harris. Having been given a free copy of the exhibition catalog, and reading the background on the show, entitled the soul exceeds its circumstances, I was conflicted, in a good way, about why the show worked so well. To say it “worked” is to diminish the subtle effect it has on you, at a purely instinctive and visual level. Even without knowing what inspired the show, you can feel these paintings are the outcome of restrained passion and love simply in the way he paints. You see image after image of modest household items, painted in an almost casual and un-assertive way, each object isolated in a field of white or Rembrandt-murk. The artist carefully depicts what he sees without fussing over hyper-realistic detail. These images immediately win you over with their humility, offered through an easy and relaxed execution. In painting after painting, you sense that Milewicz was working entirely within himself, as they say in sports, not striving to do anything more with the paint than he needed. Not trying to impress or dazzle with his skill; simply getting each object to the point where it’s all his own eye required to feel the life of the object. A brick, a shovel, a braid of challah bread, spools of thread, a hydrangea blossom, or a pair of scissors resting on a neatly folded cloth: they look as if they could smile back at you. Walking through the show, you feel as if you’re seeing tiny glimpses of the good life, in the highest sense, governed by an orderly middle-class serenity earned through hard work.

You might pause and wonder, as I did, why challah? Oh right, the artist is Jewish. Then, out of curiosity, you ask for a catalog and read the guest essay and the artist’s brief statement about his inspiration for the show. You realize this isn’t simply a refined way to make the simplest possible set of still lifes, but—looked at as a whole—this show is a fragmented narrative. These are glimpses of the happy life the artist’s grandfather led when he came to live in Brooklyn and work as a sample maker in Manhattan’s garment district. He and his wife apparently were gardeners as well. Yet you discover the deeper history behind each object when you read that Eli Milewicz weighed 60 pounds on the day Germany lost WWII and his “death march” to the Baltic Sea ended. His wife, Anna Kaplan, was also a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps. So you go back and look at each image and see the resonance of the horrific past in each painting: suddenly bricks mean a different sort of oven. A shovel is for digging both gardens and graves. Spools of thread struggle to breathe in their sealed plastic bags. And so on. If you are going to make a statement about anything, let alone something as evil as genocide, then it’s hard to imagine a more understated way to sum up an entire individual life in a set of images that have double, or triple, meanings. The show as a whole is a book of innocence and a book of experience, with both states of the soul fused together into half the images Blake required. And every one of these paintings is beautiful.

If art depends on commentary and knowledge extraneous to the image itself—and I generally hate it when that happens—then this is how it should be done. The paintings work well, entirely on their own, without background information, and yet they gain in gravity and, frankly, are even more interesting, when you hear why Milewicz was moved to paint such fraught images in such a sotto voce way. As Tom Sleigh puts it in the catalog essay: “The power of Milewicz’s images inheres in how he refuses to go in for the big teary-eyed gestures, and how ordinary objects like shovels, overcoats, and spools of thread are invested with deeper meanings. . . .but without insisting on them.” Those last five words are the key. The ‘deeper’ meaning is there if you wish to uncover it. Instruction isn’t included in the work itself, nor is it required. These are first and foremost paintings, not propositions. And very good ones at that.