Archive for February, 2015

February 28th, 2015 by dave dorsey

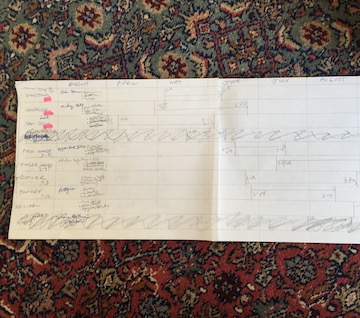

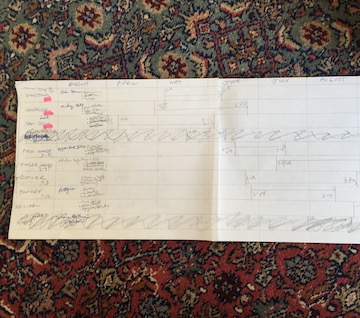

This is how I plan my year in terms of exhibitions. A pencil. A straightedge. Some lines to see how shows do or don’t overlap, so I won’t have to send the same painting to two places at once. Almost everything I would want to get into is listed. The ones at the top with the pink dot I’ve already entered. There are so few juried exhibitions anywhere that seem worth entering–surprising because it seems like an easy way to draw in revenue, with the accumulated fees. Maybe eight possibilities this year, in addition to my two-artist show at Oxford Gallery. Manifest might have something down the road that’s worth a try. I skipped several I got into last year, just because I thought it was unlikely that I could get into them again. I chart out the dates between delivery of the work and end of the show, so that I can see at a glance which ones leave enough wiggle room for me to get a painting back in order to resend to another show. Most of them overlap. The “season” is mostly in the warmer months, even though a lot of shows are in the South. Two of these are other member-run galleries like Viridian Artists (which I don’t have the money to join again), which is fine because they have good jurors, though I’m not looking to be a gallery member. Slim pickings, but a whole morning’s work to chart this out. I’d already researched and found these shows using directories of juried exhibitions on line, weeks ago, for the most part, though I found the last one only a couple days ago. Simple, humble stuff. Yet the CV I build from it matters. If I start approaching commercial galleries in New York, the long list of shows I’ve been in, and the places that have let me exhibit, will demonstrate that the work is worth considering. The lack of solo shows is a minus, but I haven’t had the body of work to do one really. I’ve sold a lot of what could expand a portfolio. I might start later this year proposing a solo show at Manifest with whatever I’ve got on hand plus the work I do between now and the fall. Then start looking for other places; but I want to knock on some doors in New York City later in the year, maybe late summer/early fall. Given the way the market works, few galleries are probably scouting for new painters, but I won’t know unless I try. I’d like to produce six smaller still lifes, like the onion I recently finished, as the core of the portfolio and then add half a dozen more from what I’ve done so far. A few very quick paintings too–I want that to become a habit.

This is how I plan my year in terms of exhibitions. A pencil. A straightedge. Some lines to see how shows do or don’t overlap, so I won’t have to send the same painting to two places at once. Almost everything I would want to get into is listed. The ones at the top with the pink dot I’ve already entered. There are so few juried exhibitions anywhere that seem worth entering–surprising because it seems like an easy way to draw in revenue, with the accumulated fees. Maybe eight possibilities this year, in addition to my two-artist show at Oxford Gallery. Manifest might have something down the road that’s worth a try. I skipped several I got into last year, just because I thought it was unlikely that I could get into them again. I chart out the dates between delivery of the work and end of the show, so that I can see at a glance which ones leave enough wiggle room for me to get a painting back in order to resend to another show. Most of them overlap. The “season” is mostly in the warmer months, even though a lot of shows are in the South. Two of these are other member-run galleries like Viridian Artists (which I don’t have the money to join again), which is fine because they have good jurors, though I’m not looking to be a gallery member. Slim pickings, but a whole morning’s work to chart this out. I’d already researched and found these shows using directories of juried exhibitions on line, weeks ago, for the most part, though I found the last one only a couple days ago. Simple, humble stuff. Yet the CV I build from it matters. If I start approaching commercial galleries in New York, the long list of shows I’ve been in, and the places that have let me exhibit, will demonstrate that the work is worth considering. The lack of solo shows is a minus, but I haven’t had the body of work to do one really. I’ve sold a lot of what could expand a portfolio. I might start later this year proposing a solo show at Manifest with whatever I’ve got on hand plus the work I do between now and the fall. Then start looking for other places; but I want to knock on some doors in New York City later in the year, maybe late summer/early fall. Given the way the market works, few galleries are probably scouting for new painters, but I won’t know unless I try. I’d like to produce six smaller still lifes, like the onion I recently finished, as the core of the portfolio and then add half a dozen more from what I’ve done so far. A few very quick paintings too–I want that to become a habit.

The tricky part in all this entry scheduling is the possibility of a sale early on, which I’d have to make contingent on being able to show the work in a later show. I could always show in the earlier exhibitions without putting a price on the work.

February 24th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Still Life with Pocket Door

If someone were to ask me right now what my painting is about, I might offer something that would probably occur to me if I were someone else appraising the work I’ve done over the past couple years. I might say Dorsey is continuing to work in several different modes: adding to the series of large jars he has exhibited in the past, doing a few suburban landscapes, and exploring smaller alla prima paintings executed very quickly, almost like Japanese sumi-e. In all of this work, he’s drawn to the ordinary and everyday. Mostly, though, he has continued his central pursuit of fairly traditional still life. His love for this genre seems to come from a variety of influences. Yet the effect of these paintings when seen together, aside from whatever virtues still life has always had, is to make one feel as if the artist is wistful, even desperate, for a world that’s fast disappearing. There’s something about these paintings that reminds one of the rag waved in the air by the uppermost member of that pile of survivors in Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa, the one trying to catch the eye of a savior on the tall ship just emerging over the horizon before time runs out on the life raft. In a time when the middle class seems to be rapidly disappearing, taking with it the promise of opportunity for most people in our society, Dorsey seems to be drawn again and again to the subject of domestic serenity as embodied in a little heirloom sugar bowl or a couple flowers from a backyard garden. Intentionally small potatoes—though, strictly speaking, he hasn’t painted any potatoes yet. Domestic happiness was the daemon of both Chardin and Vermeer, two painters who have had a powerful sway over his work so far. It isn’t a small thing, though, to have reminders of what it meant in America to have a flourishing middle class, a thriving bourgeoisie so despised by intellectuals, the economic topsoil of a robust free society, something fast disappearing in the world right now.

This might be what someone would say about the paintings in this show, though it’s merely hindsight and speculation on my part. None of this even crossed my mind as I’ve done this work, MORE

February 22nd, 2015 by dave dorsey

For an bit of interesting commentary on the power of contemporary media, try the first episode of Black Mirror. It’s also a sidelong statement about . . . well, watch. The series as a whole is well done.

February 22nd, 2015 by dave dorsey

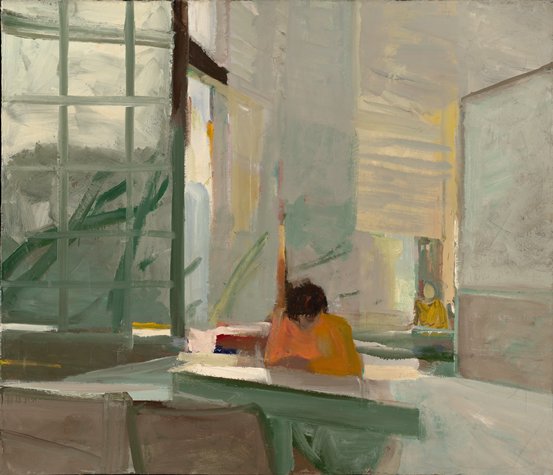

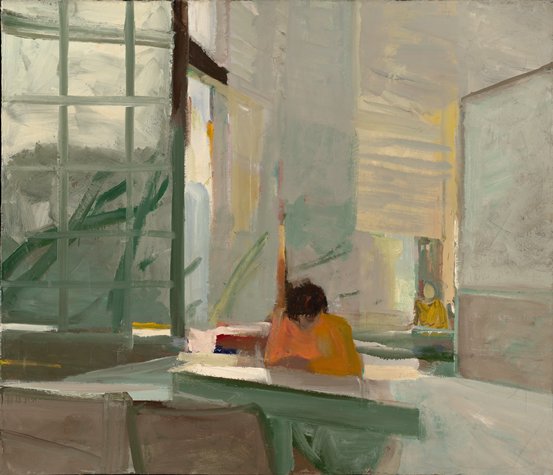

Dining Room into Living Room, Mark Karnes, 2009-2012, acrylic on Masonite

In fortuitous lulls during the Siberian Express of snow and frigid temperatures here in the Northeast during the past week, I drove six hours to Maryland to see two fantastic exhibits, both devoted to “perceptual painting.” One, organized by Matt Klos, tracks the largely unrecognized history of this movement, showing how perceptual painting enables representational art to evoke a liminal, dreamlike intimation of a world around and within the surface of things. That may be a pretentious-sounding way to say that perceptual painters enable you to see what they saw, mostly through direct observation, but they also convey a loving, sustained hunger to evoke something much larger, the poetry of the everyday. I’m getting ahead of myself, though. I want to write a long post about both shows, or maybe several posts, when I’ve tackled some other things on my plate, and this is simply a quick reminder for anybody within a few hours of Annapolis to invest an afternoon on these shows before they come down. It’s some of the most compelling painting being done right now, and it’s also an interesting attempt to further define what “perceptual painting” is, in the wake of earlier shows, such as the one recently at Manifest and a year ago at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art. It kills me not to be able to attend the exhibition events today, but I pass this note along from Matt Klos for anyone able to attend:

My curator’s talk for “A Lineage of American Perceptual Painting” has been moved to Wednesday, February 25th at 5:30pm located at St. John’s College in the Drawing Room adjacent to the Mitchell Gallery. There will be ample time to walk through the gallery before and after the talk. St. John’s College, Mitchell Gallery, 60 College Ave, Annapolis, MD 21401

A panel discussion for the exhibition will be held this Sunday February 22nd at 3:00pm also located at St. John’s College. Follow signage when you arrive to the gallery… we will either meet in the auditorium or the drawing room depending on turnout. Although not required please call the gallery to rsvp for both events,

410-626-2556.

St. John’s College, Mitchell Gallery, 60 College Ave, Annapolis, MD 21401

“Lineage” Artists and Panel Discussion participants will include:

James Fitzsimmons

Elizabeth Geiger

Philip Geiger

Mark Karnes

Scott Noel

Charles Ritchie

Aaron Lubrick and Matt Klos will moderate. Several questions will be asked of the panel including this one, The painter Jake Berthot in a letter to Ryan Smith once wrote, “The mind lies and is capable of making a justification for anything. The eye and the hand are incapable of lying. Look with your heart and it will tell you through your eye what your hand needs to do.” Can you talk to us about what you think Mr. Berthot may have meant? What does that statement mean to you? I hope you’ll come join the conversation.

Special guests Erin Raedeke, David Campbell, and John Lee will also attend the Panel Discussion. These artists currently have work on view at Anne Arundel Community College in the Cade Gallery in an exhibition “Subject & Subjectivity” curated by Matthew Ballou. On the day of the Panel Discussion (Sunday, Feb. 22nd) artists will be on hand in the Cade Gallery to discuss the exhibition starting at 1pm. John A. Cade Center for Fine Arts, Cade Gallery, 101 College Pkwy, Arnold, MD 21012

February 20th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Orange Sweater, Elmer Bishoff

February 16th, 2015 by dave dorsey

My lifelong, simmering interest in Martin Heidegger, plus my recent quick rereading of early Nietzsche, has a couple friends wondering if I’ve become a dreaded existentialist, whatever that is. (No doubt this would mean someone who understands what “existential threat” means.) The answer would be “no.” My faith, humble and simple and nonsectarian as it is, remains unshaken—it’s a way of life, not a set of propositions about the world. But Heidegger keeps appearing in my path, even when I’m not seeking out books or essays about him. For example, while painting this week, I caught up with some of the latest episodes of In Our Time, a great, brisk discussion from the BBC about almost any subject as long as it’s dense with information: history, music, religion, art, and philosophy. I clicked on the “Phenomenology” episode and listened to a discussion that repeatedly reminded me of why I started painting years ago, as a way of seeking “meaning.”

Melvyn Bragg had three guests: Simon Glendinning, from the European Institute at the London School of Economics, Joanna Hodge, from Manchester Metropolitan University, and Stephen Mulhall, from the University of Oxford. The discussion turned out to be a sort of back door into an examination of what has generally been called “existentialism” though none of the panelists ever once used the word, instead referring to Heidegger and Sartre as phenomenologists because their work descended from Edmund Husserl’s. This off-the-cuff dissection of phenomenology was articulate and effective—and quick—so I’m going to reproduce some of it here, partly because by the end of the podcast I was struck by how much painting is, or should be, a phenomenological exploration.

Here are portions of the conversation, paraphrased and condensed in places, starting with an overview whose bearing on representational painting should be glaringly obvious:

Stephen Mulhall:

Phenomenologists are fascinated and struck by the fact that we grasp and comprehend all of the various entities that the world throws at us in the course MORE

February 14th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I’m an avid admirer of Suzie MacMurray’s work, after stumbling onto her show at Danese/Corey in 2013 and spending quite a bit of time there absorbing it. I got an email from her about a new installation, Cloud, to commemorate the loss of British soldiers in the First World War. Wish I could get across the pond to see it, but I’ll be checking for glimpses via the Internet. Sounds intriguing, and substantial, and no doubt brilliantly done.

February 12th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Memorial Art Gallery at Night, Jim Mott, oil on board

I had a desultory conversation with Jim Mott recently, touching on why we paint, so I’m just going to leap into it in media res:

Jim: In a better world the agenda for painting since the Sixties might have been to integrate the abstract and the real.

Dave: Everybody tries to some degree. I think that’s really what painting is, even the most abstract is representational and vice versa.

J: But to have the dialog between them . . .

D: Right. What I love about your work is that you create that tension between the painterly quality and the image.

J: My worldview isn’t defined very well. I try to do tighter stuff but it doesn’t work. I would love it if I could do a Van Eyck. But I think it doesn’t mesh with what reality is.

D: How so? MORE

February 10th, 2015 by dave dorsey

This story in the Sunday Times seems like a brief scenario from a Kurt Vonnegut novel, as he might have imagined the world decades into the future. A high-tech, high-security warehouse where art can be stored and never need to be moved ever again, while traders buy and sell it at their computers, capitalizing on fluctuations in price. The physical reality of the artwork ceases to matter or even mean anything, since no one ever needs to see it again. The headline for this report yesterday in the print edition was “Art in Residence” but now, online, it has been improved to “Art for Money’s Sake.” From the article:

The wealthiest Americans have grown wealthier since the Great Recession, and many are investing their wealth in art. Especially with bonds and other assets offering rock-bottom yields, the art market — where reports of record-high sales now emerge regularly — has an obvious appeal. According to a survey last year by Deloitte and ArtTactic, an art-research firm, 76 percent of art buyers viewed their acquisitions as investments, compared with 53 percent in 2012. And with more collectors viewing art as a financial investment, storage can become an artwork’s permanent fate.

Largely hidden from public view, an ecosystem of service providers has blossomed as Wall Street-style investors and other new buyers have entered the market. These service companies, profiting on the heavy volume of deals while helping more deals take place, include not only art handlers and advisers but also tech start-ups like ArtRank. A sort of Jim Cramer for the fine arts, ArtRank uses an algorithm to place emerging artists into buckets including “buy now,” “sell now” and “liquidate.” Carlos Rivera, co-founder and public face of the company, says that the algorithm, which uses online trends as well as an old-fashioned network of about 40 art professionals around the world, was designed by a financial engineer who still works at a hedge fund. The service is limited to 10 clients, each of whom pays $3,500 a quarter for what they hope will be market-beating insights. It’s no surprise that Rivera, 27, who formerly ran a gallery in Los Angeles, is not popular with artists.

February 8th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Onion on a Carved Table, oil on linen

If you wanna kiss the sky better learn how to kneel. –U2

I posted a picture of Onion on a Carved Table a while back in a state of trepidation right before I started work on the onion, which I’d saved for last. In the post I talked about how I had to deal with the anxiety of tackling that onion skin. I worked through it, and I’m happy enough with the results that this will be in the two-artist show in March at Oxford Gallery.

I’m at the same point in a larger and more involved painting right now, hoping to finish it in time for the show, as well as submit it for consideration for the Finger Lakes Exhibition at Memorial Art Gallery. The current painting is completely done except for its most complex object, in the foreground, an ornate wine bottle holder that is more or less a family heirloom, which sits, in the picture, on the countertop in our kitchen, with the sink behind it. It is slightly tarnished silver, and capturing the way that surface shines and also doesn’t quite shine in places is enormously challenging, partly because there isn’t a flat point anywhere on the surface of that metal cup, embossed with tiny grapes and pears and vines. I woke up a couple nights ago at 2:30 and couldn’t get back to sleep, which hasn’t happened much this winter so far, so I came downstairs and looked at the progress on the painting and felt an impulse to toss it out (which must overcome any painter at some point). I didn’t, but sat down in the artificial light and worked on it for two hours, long enough to feel that I may manage to complete it satisfactorily by the end of the month. At the end of February I will have invested two months of daily work into this painting, seven days a week, longer than I’ve put into any previous work. Essentially, right now, it’s more a matter of will and desire than skill: if I can work quickly enough on the first coat of paint and then slowly enough on the successive modifications to it, within the time left to me, it will come together. But that’s more a question of character, focus, determination and perseverance–as well as an ability to suppress the anxiety that two months of work will end up wasted. It won’t. But, even if its satisfactory, the painting might not be exactly what I’d hoped or what I know I could have done, and that’s almost as discouraging as the prospect of giving up.

My familiarity with this kind of inner test of tenacity is why two recent movies about the creative process moved me so deeply: Birdman and Whiplash. I didn’t think Birdman could be equalled for the way in which it portrayed the pain of creative effort, and the joy of its fulfillment. That link between the pain of struggle and an ability to be joyful as a result of it is what I heard in my recent rereading of Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy where he had already begun to suggest how art can be a counterforce to nihilism. It can reconcile you to suffering and transform it into joy. A little painting, as much as a Greek tragedy, can be a way of affirming that joy in life as a whole, with all of its unavoidable suffering and tragedy. This may sound a little pompous in relation to worries about how to paint a wine bottle holder, but when you are in that state of doubt about your ability to create something that does affirm the joy of appearances, the prospect of failure can feel excruciating. On top of whatever struggle you happen to be going through in your non-painting life–which was Nietzsche’s real subject, the agonies of life itself. Which is where Whiplash–to get back to my point–may have surpassed Birdman in the way it shows how extreme creative effort is willing to put up with any level of sacrifice, and those stakes are raised to harrowing levels in the movie, before the drummer can break through to something greater than what he’d ever been able to do, because joy was waiting there. Even if that joy is nothing but your own response to having done exactly what you’d hoped and, even so, still feeling more than pleasantly surprised by the results.

I’ve got a lot of work left to do before I get there. Six weeks in, this is the hard part.

February 6th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Tolstoy

In a passage replete with quotable sentences from the linked article: “Levin at last realizes that if one lives rightly moment to moment, one can sense life’s meaningfulness, but one will still not be able to express it.” From a fantastic essay in The New Criterion about how science has narrowed and blinded us to its own limits, on the path toward wisdom. One can substitute the word “literature” with the word “art” at the end of the second paragraph and do no harm to the meaning of the paragraph:

Tolstoy in particular shaped Wittgenstein’s thought. As a soldier in the Austrian army, Wittgenstein carried copies of Tolstoy’s stories and Gospel in Brief everywhere. His friends jokingly referred to him as “the man with the Gospels.” The end of the Tractatus makes sense the moment one recognizes it as a loose paraphrase of Levin’s meditations in Part VIII of Anna Karenina.

For Wittgenstein, logic and science are indeed powerless to address questions of life’s meaning. “We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all,” Wittgenstein explains. But that does not mean these problems do not matter. It means that they must be addressed otherwise—for example, by literature.

Like Levin, Wittgenstein reasons that “the sense of life” cannot be a fact in the world, but must lie outside it. It cannot belong to the chain of cause and effect, or anything connected with natural laws, because it must illumine life as a whole. Or as Levin comes to understand: “If goodness has causes, it is not goodness; if it has effects, a reward, it is not goodness either. So goodness lies outside the chain of cause and effect.”

Levin at last realizes that if one lives rightly moment to moment, one can sense life’s meaningfulness, but one will still not be able to express it. What changes for him is not some fact in the world, but the world itself, which, as Wittgenstein paraphrases the point, “must wax and wane as a whole.” Ultimate questions are not answered, but they vanish in the face of meaningfulness and goodness directly experienced. Wittgenstein at his most Tolstoyan explains: “The solution of the problem of life is seen in the vanishing of this problem. (Is not this the reason why men to whom after long doubting the sense of life became clear, could not then say wherein this sense consisted?).” Russell notwithstanding, the genuinely inexpressible is indeed real. We come to know it not by logical deduction but because “it makes itself manifest. That is the mystical.”

When Levin comes to this realization, he understands that meaningfulness has always been there right before his eyes, hidden in plain view. Cloaked in its ordinariness, it is a daily miracle. “And I watched for [material] miracles, complained that I did not see a miracle that would convince me,” Levin thinks. “And here is the miracle, the sole miracle possible, continually existing, surrounding me on all sides, and I never noticed it!”

February 4th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Two Cheese Cubes, 2011

I saw comparatively few exhibits over the past year, but I did manage to catch Wayne Thiebaud at Aquavella, where we lingered quite a while in front of his work. It appeared to be a selection from throughout his career, though I’d hoped for more of the recent large non-urban landscapes. It did have at least one smaller work in that mode: a luminous view of a shoreline with a file of beachcombers, who appeared, on closer inspection, to be armed with metal detectors. It’s no shock that Thiebaud is whimsical enough to turn a potentially grubby-looking subject into something gorgeous. The show in general was as energizing as I’d hoped it would be, and it offered some interesting surprises including a small self-portrait in graphite, a pencil sketch that captured his young likeness with great economy despite the paper’s dimensional constraints. You could discern the slightly pensive good cheer behind his eyes even at that small scale. His handling of paint varied in surprising ways even within individual paintings. He trowels the paint onto a surface in his backgrounds and in uniform areas of color, but when it comes to rendering the human body, the paint becomes smooth and less visible, as if it’s been rubbed smooth from so much polishing. So he’ll show you a figure where the background might be so thick it looks as if he was able to drag a fingertip around the edge of his sitter’s figure, almost as if to indicate a saintly aura, but then the arms are so carefully finished the paint disappears into the illusion it creates. My favorite: a brilliant little painting of two blocks of cheese, as minimal as a Stella, but filled with the light that Thiebaud owns. Simple or not, he can work on a painting for years.

He extolled the value of “long looking” in an interview with Art News about Morandi’s influence on his work, and I wholeheartedly concur with every word: “There are such good lessons to learn from looking at his work. They have to do with certain propositions that I think serious painters need to be aware of. One of them, I think, is the wonder of intimacy and the love of long looking. Of staring but at the same time moving the eye, finding out what’s really there, and there are so many things that are subtle and may look like something at one moment but not the next. There’s always that kind of “not quite” with Morandi and yet the feeling of totality is so nicely complete. It’s always a joy to look at his work.”

Aquavella is one of the nicest art spaces I’ve visited in New York City, a former residence, not nearly as spread out as the former garages in Chelsea, but with very high ceilings, including one room with rows of sculpted busts sitting far up in a recessed alcove that runs along the wall just beneath the crown molding. It’s a phalanx of likenesses of luminaries from the Enlightenment. I recognized Voltaire and hazarded some guesses about many of the others.

February 1st, 2015 by dave dorsey

Respite, encaustic on panel, Sharon Gordon

“Eternity is in love with the productions of time.” –William Blake

At the Oxford Gallery here, Jim and Jinny Hall have assembled a finely unified show of two regional artists, Karl Heerdt and Sharon Gordon, who are working in the stylistic neighborhood of Tonalism, a school of art that has drawn Jim’s devotion as a collector and dealer for many years. You’ll see many of Tonalism’s earmarks in the work of both painters: an emphasis on evoking landscape rather than denoting its details, a sense of diffuse twilight, and quiet hints of transcendence. In the 19th century, Tonalism was in part a response to the work of thinkers like Emerson and Thoreau, whose writing affirmed a Yankee Romanticism, a perception of the world where the human soul and the natural world sprang from one unifying spiritual source. I suspect neither Heerdt nor Gordon would go so far as to call themselves transcendentalists, but in the current work of both painters, the indeterminacy of what’s being depicted gives their elusive images the sense of withholding as much as they disclose–hinting at a life behind appearances that glances out at the viewer and then withdraws. The paintings return your gaze in a way that makes you want to know more about what’s happening behind the look of things. Heerdt lives and works mostly around Buffalo. Of all his work, his simple scenes drawn from the Niagara River have always captured and held my attention the longest. One of these, in this show, a very small oil, includes little more than a hump of snow to indicate the bank of the river and then a stretch of indistinct water with a few whitecaps, a scene nearly devoid of subject matter–or distinctly even visible objects. It has the simplicity of a Milton Avery, dividing two dominant colors/values diagonally. Yet it’s intensely recognizable, a glimse of our region of excruciatingly familiar gray winter light that,in January for anyone living on the shore of Lakes Erie and Ontario, becomes the dull, dreamy ground of one’s consciousness. Yet it’s masterful and seemingly effortless, his handling of the paint as essential to the effect as the way he seeks that illusion of our somber Rust Belt twilight. His other work is every bit as masterful, a tangle of brushwork up close, but, a few steps away, an amazingly precise evocation of a particular hour’s slant of light. One small oil, of another river, in Yellowstone, with vaguely purple reflections on the water, looks as if it could have been done en plein air, in a single sitting, and yet there isn’t a false move or needless bit of paint anywhere in the image. In other words, Heerdt is getting better and better. He told me at the opening that he’s trying to simplify his methods in a radical way, working toward an image from four, three, even two abstract areas of value, building outward from that flat map of light and dark. He said he’s also working in more hints of color, sometimes almost arbitrary, into what has been his past adherence to blues, grays, browns and whites. He has started a series of much larger canvases, and I can’t wait to see what emerges from that shift in scale.

Sharon Gordon’s experiments with encaustic and cold wax form the core of her portion of this show, and these mostly square, fairly small images hover at the exact halfway point between representation and abstraction. They work perfectly in either mode. They evoke Turner as much as the Tonalists, and some verge on color field painting. MORE

This is how I plan my year in terms of exhibitions. A pencil. A straightedge. Some lines to see how shows do or don’t overlap, so I won’t have to send the same painting to two places at once. Almost everything I would want to get into is listed. The ones at the top with the pink dot I’ve already entered. There are so few juried exhibitions anywhere that seem worth entering–surprising because it seems like an easy way to draw in revenue, with the accumulated fees. Maybe eight possibilities this year, in addition to my two-artist show at Oxford Gallery. Manifest might have something down the road that’s worth a try. I skipped several I got into last year, just because I thought it was unlikely that I could get into them again. I chart out the dates between delivery of the work and end of the show, so that I can see at a glance which ones leave enough wiggle room for me to get a painting back in order to resend to another show. Most of them overlap. The “season” is mostly in the warmer months, even though a lot of shows are in the South. Two of these are other member-run galleries like Viridian Artists (which I don’t have the money to join again), which is fine because they have good jurors, though I’m not looking to be a gallery member. Slim pickings, but a whole morning’s work to chart this out. I’d already researched and found these shows using directories of juried exhibitions on line, weeks ago, for the most part, though I found the last one only a couple days ago. Simple, humble stuff. Yet the CV I build from it matters. If I start approaching commercial galleries in New York, the long list of shows I’ve been in, and the places that have let me exhibit, will demonstrate that the work is worth considering. The lack of solo shows is a minus, but I haven’t had the body of work to do one really. I’ve sold a lot of what could expand a portfolio. I might start later this year proposing a solo show at Manifest with whatever I’ve got on hand plus the work I do between now and the fall. Then start looking for other places; but I want to knock on some doors in New York City later in the year, maybe late summer/early fall. Given the way the market works, few galleries are probably scouting for new painters, but I won’t know unless I try. I’d like to produce six smaller still lifes, like the onion I recently finished, as the core of the portfolio and then add half a dozen more from what I’ve done so far. A few very quick paintings too–I want that to become a habit.

This is how I plan my year in terms of exhibitions. A pencil. A straightedge. Some lines to see how shows do or don’t overlap, so I won’t have to send the same painting to two places at once. Almost everything I would want to get into is listed. The ones at the top with the pink dot I’ve already entered. There are so few juried exhibitions anywhere that seem worth entering–surprising because it seems like an easy way to draw in revenue, with the accumulated fees. Maybe eight possibilities this year, in addition to my two-artist show at Oxford Gallery. Manifest might have something down the road that’s worth a try. I skipped several I got into last year, just because I thought it was unlikely that I could get into them again. I chart out the dates between delivery of the work and end of the show, so that I can see at a glance which ones leave enough wiggle room for me to get a painting back in order to resend to another show. Most of them overlap. The “season” is mostly in the warmer months, even though a lot of shows are in the South. Two of these are other member-run galleries like Viridian Artists (which I don’t have the money to join again), which is fine because they have good jurors, though I’m not looking to be a gallery member. Slim pickings, but a whole morning’s work to chart this out. I’d already researched and found these shows using directories of juried exhibitions on line, weeks ago, for the most part, though I found the last one only a couple days ago. Simple, humble stuff. Yet the CV I build from it matters. If I start approaching commercial galleries in New York, the long list of shows I’ve been in, and the places that have let me exhibit, will demonstrate that the work is worth considering. The lack of solo shows is a minus, but I haven’t had the body of work to do one really. I’ve sold a lot of what could expand a portfolio. I might start later this year proposing a solo show at Manifest with whatever I’ve got on hand plus the work I do between now and the fall. Then start looking for other places; but I want to knock on some doors in New York City later in the year, maybe late summer/early fall. Given the way the market works, few galleries are probably scouting for new painters, but I won’t know unless I try. I’d like to produce six smaller still lifes, like the onion I recently finished, as the core of the portfolio and then add half a dozen more from what I’ve done so far. A few very quick paintings too–I want that to become a habit.