Archive for April, 2012

April 30th, 2012 by dave dorsey

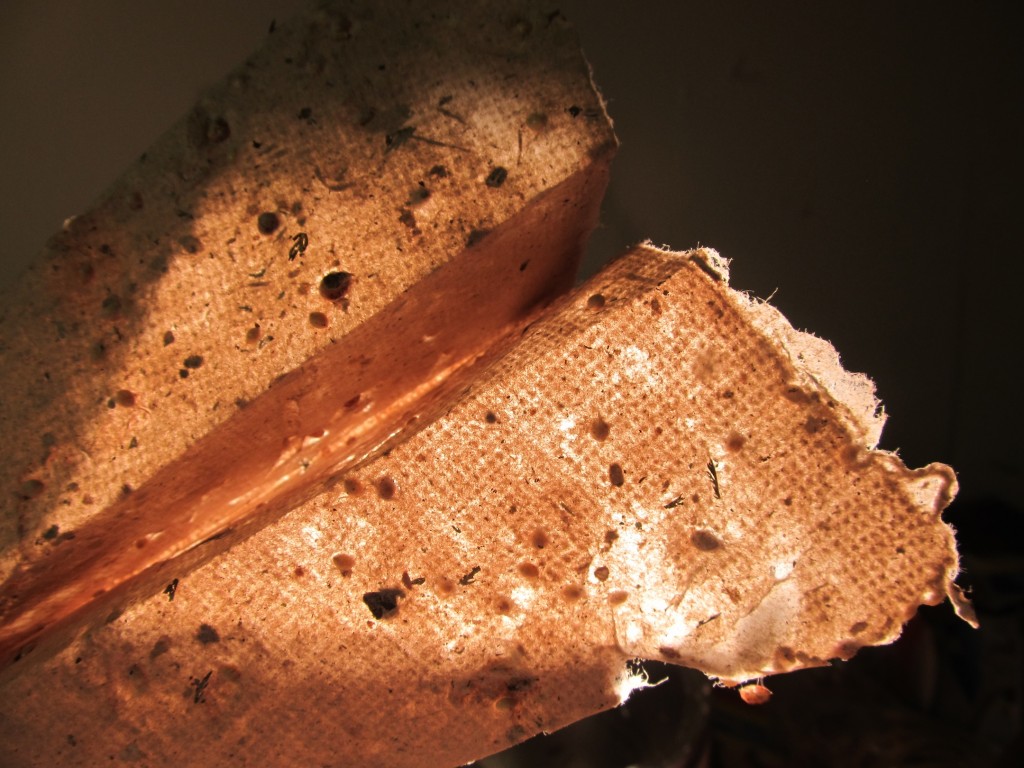

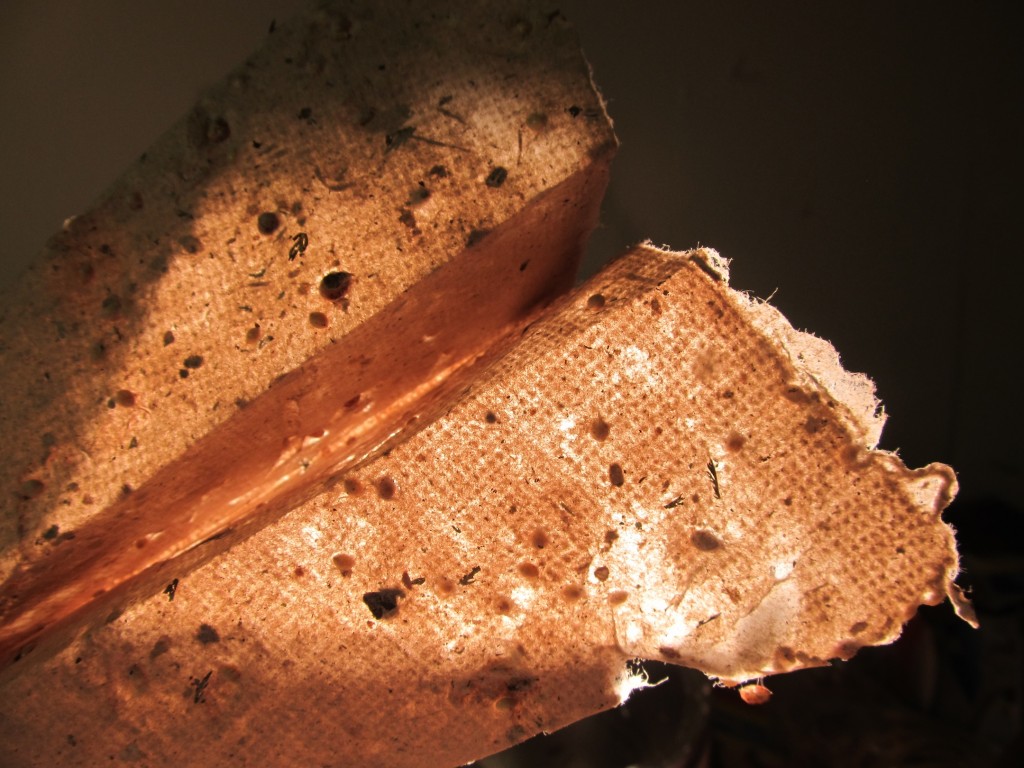

A shipment of small, light aircraft arrived at my door yesterday in Pittsford: a dozen sheets of hand-made paper impregnated with wildflower seeds. I will fold them into airplanes and then “return them to flight” wherever I can find a place they might actually germinate. I know exactly where I’m going to set at least one of these birds free, maybe all of them—from a promontory in the Finger Lakes near Bristol—and I’m betting that nobody else is going to get the hang time I’ll get, if the wind is at my back anyway. (I’m a guy, so I think everything’s a competitive event, even if I’m totally alone . . .) But I also want to try for an urban area or two, maybe Central Park when I’m in New York in a few days, or Brooklyn.

Jennifer Wenker made the airplanes as an art project to complete her MFA at University of Cincinnati this year. She was inspired to create this campaign in response to a USDA program for poisoning “nuisance birds”: “Bye Bye Blackbird” in which, she says, 2 billion birds were poisoned in 2009. I met her on a swing through her school with Rush Whitacre on my way to Louisville recently. So now I have a stack of wonderfully pebbly sheets of paper, some with wildly random deckle edges, and my next step is to turn them into planes.

I love this project because I love birds, and planting things, and the unassuming childlike simplicity of the whole project. The image of the airplane, the concept behind the project—it’s all tremendously simple, yet loaded with poetic resonance. As Jennifer put it: “We’ve taken over so much of the landscape, it can be hard to find a place where seeds can More

April 24th, 2012 by dave dorsey

In a fine article in The Brooklyn Rail about pursuit of spectacle and the influence of money on art, Dore Ashton quotes Friedrich Nietzsche:

Far from the market place and from fame happens all that is great: far from the market place and from fame the inventors of new values have always dwelt.

April 12th, 2012 by dave dorsey

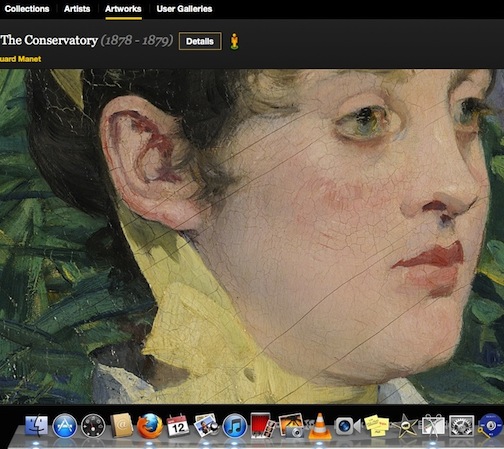

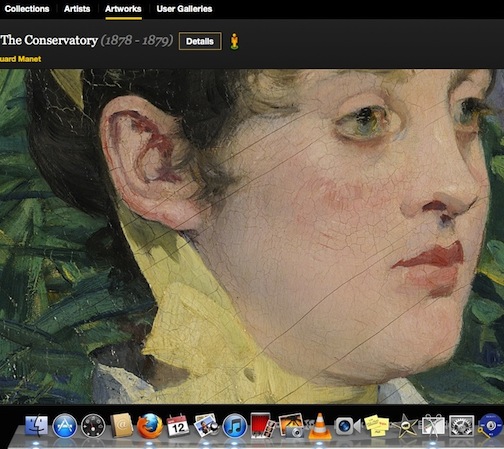

Screen grab of Manet zoom

I’d forgotten the Google Art Project existed until I read Roberta Smith’s celebration of it in the NYTimes just now, on-line. It has expanded considerably since last year, and though I don’t think this is going to suck as many hours out of my life as Halo has, over the years, it could be a contender. It’s frustrating to read how resistant many museums and rights-holders continue to be, given the potential for total access this project could offer to nearly anything and everything ever painted–and what a gift that would be to nearly anyone interested in art. Painting is meant to be seen, not stored away in private rooms. The sad reality of art, in general, is that the public has access to only the tiniest tip of the iceberg. Of work that’s been done over the centuries, the vast majority sits in vaults or in places only few can access–it’s as good as gone, a sea of unreachable, unknowable dark matter for most of us. Those rights-holders who continue to stand aloof from the Google project should bear in mind that there continues to be no substitute for actually standing a few feet away from a work of art: no reproduction can fully capture what you see by looking at the living, physical object. I spent years scratching my head over Bonnard’s critical standing until I turned a corner at MoMA and stood before one of his surfaces, astonished. And I’ve also felt deflated looking at work that thrilled me in books or on the web, only to see how clumsily the painter actually handled the medium. Yet if my quick sample of Google’s project is any indication of its potential, it could come pretty close to the experience of seeing the actual work, and this would be an enormous boon to both artists and scholars. When I went to this site this morning, I clicked on the first image that appeared, Manet’s In the Conservatory, and double-clicked to zoom a little closer. Then I did it again, expecting blur or those squiggles of photographic compression. Yet the image stayed crisp. Again, I clicked, with no loss of resolution. By the time I was done, I was as close as a kiss to this lovely model’s face. Nothing but her cheek and lips filled the screen–a pleasant prospect in and of itself, but it also showed me the actual surface of the canvas so distinctly I could make out how the thing had been rolled for storage. The diagonal cracks in the oil paint clearly showed that someone had removed it from the stretcher and rolled it, starting with the point of one corner and ending at the opposite one. I don’t especially need this information, but someone else might, and yet what I do want is to see the quality of his paint, the perfect, delicate skin tone, the evidence, yet again, of Manet’s seemingly cavalier brushwork, all the effortless mastery so clearly there in every square inch of his best work. So bring it on, Google. Get it all on-line. Everything. Picasso! Braque! Artists I’ve never heard of. Right now, I am Gary Oldman in The Professional, crazed and, well, frankly a little goofy with bloodlust, telling his henchman: Bring me everyone.

Whataya mean everyone?

Oldman roars: EVERYONE!

April 12th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Some observations that apply, some more than others, to painting as well.

From: A Lesser Photographer, Ten principles for Rediscovering What Matters, C.J. Chilvers

- Artists thrive on constraints

- Go amateur: be remarkable, not marketable.

- It’s about the image, not how you make it

- Tell stories: learn to write or collaborate with a writer

- What you keep returning to in your work is your visual home

- Don’t improve on what you see

- Show only your best work

- Control the way you show it

- Keep it legal (not so much for paintings; nota bene, Richard Prince)

- Be grateful: “While others let beauty pass them by, we recognize it, experience it and share it with the world.”

April 9th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Lifecycle IV, detail

This morning, the New York Times has a story on how, in the late 50s and 60s, the Ford Foundation became, essentially, a central patron of creative work for struggling artists in the U.S. The story quotes from letters James Baldwin wrote to the foundation, asking for funds to help him keep writing, and then goes on to explain that he used the money he was awarded to support work on Another Country:

It was 1959, six years before Congress created national endowments for the arts and humanities to support struggling artists and cultural institutions. For Baldwin, who was straining to finish a novel and pay personal debts, the place to turn for cash was neither the government nor any literary agent but to a relatively obscure foundation official named W. McNeil Lowry. Mr. Lowry had the last word in deciding which artists, writers and performers would receive grants from the Ford Foundation, the richest private source of cultural largess at the time. This month letters to and from Mr. Lowry . . . were opened to researchers at the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, N.Y.

There’s nothing unusual anymore about getting a grant to make art, but the focus on the personal, informal-sounding letters asking for a gift of money struck a chord, mostly because my friend Rush Whitacre, at artist in Brooklyn who plans to move home to Ohio soon, has been writing exactly the same kind of letters to unsuspecting potential patrons over the past few months. Currently, he’s writing to Jerry Bruckheimer, the movie mogul, asking Mr. Bruckheimer to please pay off Rush’s college debt in exchange for the gift of Rush’s best painting, an enormous canvas of sunflowers inspired by Van Gogh. (This letters project was also inspired by Van Gogh’s letters to his own patron, his brother Theo.) Most artists I know, like Rush, have little money to support their work, and—like Rush, who works as a security guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—have other jobs to pay the bills, leaving little time left to actually create art. Rush has never met Mr. Bruckheimer, and undoubtedly never will, but this doesn’t stop him from writing a daily letter—as well as a poem—imploring the producer to dip into his exceedingly deep pockets and become Rush’s patron.

Rush’s audacity never fails to amuse me—especially because it’s almost More

April 5th, 2012 by dave dorsey

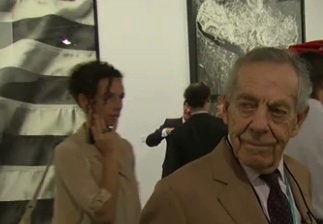

Gary Lee Cordray

I read an extremely funny book yesterday: Bad Ass Art. It was written and self-published a couple years ago by Gary Lee Cordray, as his thesis project for a degree in art at Ohio University. It lays out essentially how to become a Bad Ass Artist, a process that begins by rolling dice in order to determine all the elements you need for your work to add up to a score of either +6, +12, +18, or +24, in the Bad Ass Art-Making system. Or if you already have an idea for a work of art, you can calculate how all the work’s elements add up, and then modify your notion so that you get a score which is a multiple of 6 points. (You don’t need to understand this. I don’t. I don’t think Lee wants you to.) There are four levels you can attain, the lowest being Badass Art. Next up, Fine Art. Then, Badass Fine Art, and finally, at the highest level, High Art. A few examples of how to score your work by identifying Bad Ass elements: Big Watery Eyes, +1; Jars, Bottles or Urns, +1; Glowing, as if Magical or Divine, +1; Bar codes, pills, or price tags, +1; Realistic-looking or lifelike, +1; Part of a coherent series or body of work, +1; Big sharp teeth/fangs, +1; Reflections, +1; Add wings, +1, and so on. The list of elements runs to 80 elements in four categories: Dark, Weird, Sexy, and Artistic. To be Bad Ass, a work needs to draw elements from at least three categories. There is no justification for any of the scoring rules, of course, but as you thumb through it, the prose lulls you into nodding and adding up numbers from your own work, thinking, huh, OK, that canvas I finished last week, hm, three, four points, no, five. No! Only five! OMG. Fail!

The opening of the book has it’s most rewarding voice:

“Welcome to Bad Ass Art; a mode of art making that has set many artists free from thinking too hard More

April 3rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

From one of the most trustworthy critics, in the NYTimes, commenting on Morley Safer’s piece about the world of art on 60 Minutes:

“Have [the super-rich and speculators] ruined art? No, they’ve just created their own little art world that has less and less to do with a more real, less moneyed one where young dealers scrape by to show artists they believe in, most of whom are also scraping by. Mr. Safer should visit that one sometime, without the cameras, and try to see for himself, beyond the dollar signs. Either that or he should just come clean: He could not care less about the new or how it makes its way, or doesn’t, into the world and into history.”

–Roberta Smith

Arthur Danto might argue against “the new” and suggest that art history is over, but Smith is absolutely right about where someone ought to be looking for the real struggle, and how the artist’s old companion, despair, is a lot more prevalent than big money wherever that effort is taking place.