November 29th, 2012 by dave dorsey

“Freud said the goals of the artist are fame, money, and beautiful lovers. Based on my artist acquaintances, I would say this holds true today. What have changed, however, are the goals of the art itself. Do any exist?

“How did the art world become such a vapid hell-hole of investment-crazed pretentiousness? How did it become, as Camille Paglia has recently described it, a place where ‘too many artists have lost touch with the general audience and have retreated to an airless echo chamber’?”

Why the art world is so loathesome. Eight theories from Slate: MORE

November 27th, 2012 by dave dorsey

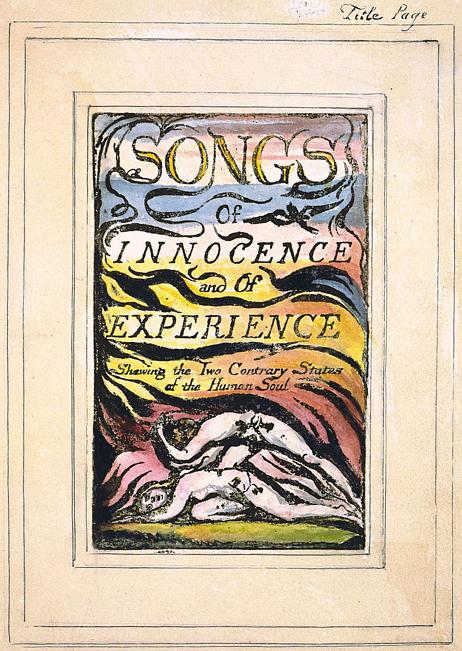

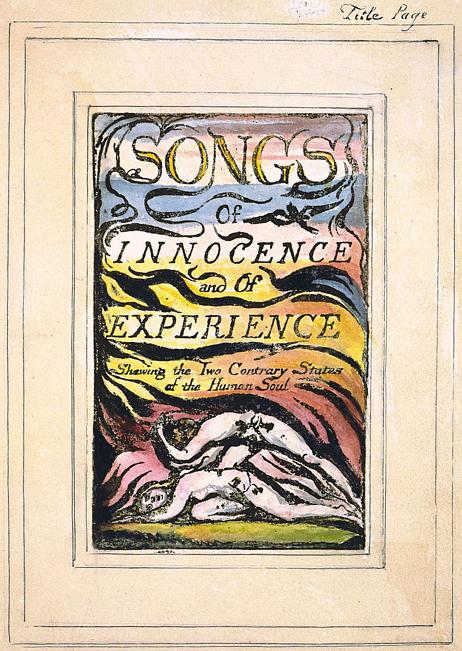

“In anticipation of the birthday tomorrow of the beloved William Blake – the greatest poet of London – it is my delight to publish his Songs of Innocence of 1789 today. When Blake was developing his copper plate printing technique that would enable him to become his own publisher and be free of the restrictions of others, he wrote, “I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Man’s.” So I think we may assume that if Blake were writing now he would embrace the opportunity of publishing his work freely upon the internet.” —Spitalfields Life

“In anticipation of the birthday tomorrow of the beloved William Blake – the greatest poet of London – it is my delight to publish his Songs of Innocence of 1789 today. When Blake was developing his copper plate printing technique that would enable him to become his own publisher and be free of the restrictions of others, he wrote, “I must Create a System, or be enslav’d by another Man’s.” So I think we may assume that if Blake were writing now he would embrace the opportunity of publishing his work freely upon the internet.” —Spitalfields Life

November 17th, 2012 by dave dorsey

November 9th, 2012 by dave dorsey

Dave Hickey

Little slow to see this, but have to pass it along, from The Guardian. “When I asked students at Yale what they planned to do, they all say move to Brooklyn – not make the greatest art ever.”

November 6th, 2012 by dave dorsey

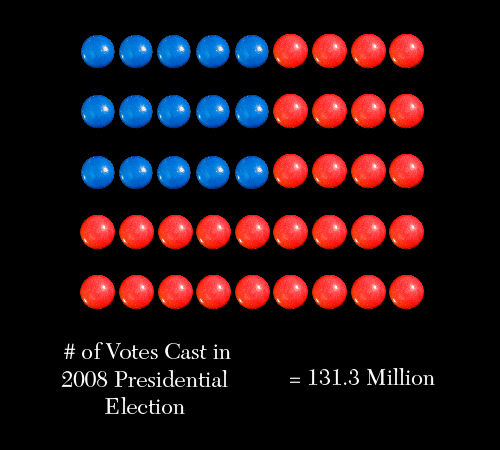

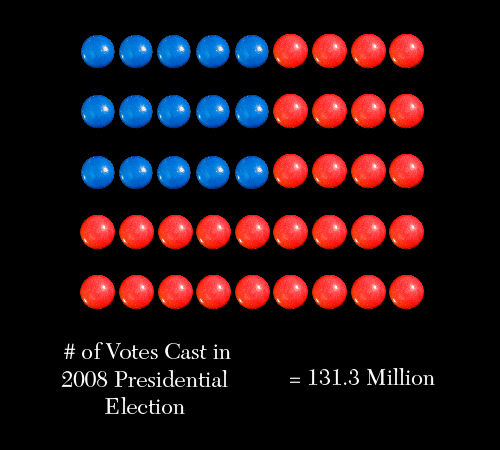

The election in M&Ms

Candy! A language I understand. Finally. The basics of this election, explained with M&Ms. Finally, Barry and Mitt have my attention . . . Not to quibble, but could I get this in Reese’s Pieces?

November 3rd, 2012 by dave dorsey

Jim Mott

Jim Mott, my friend the itinerant artist, is in the middle of his Great Lakes tour, which takes him through Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit and a couple stops in Ontario. He stays with hosts who give him room and board in exchange for a painting of their surroundings. It’s probably the most radical way of being an artist I know. It takes money out of the equation entirely and puts him into a role somewhat like a mendicant monk, or the poet Basho, in his walk around Japan. This kind of itinerant art connects him with people in an extremely personal way—he’s invited to infiltrate their lives and reflect their world back to them through his quickly executed paintings. He becomes a humble servant rather than a seer, producing work that’s instantly recognizable and meaningful, rather than an image that requires deciphering and commentary by anyone other than the recipient. In other words, his project turns a lot of things upside down and the result is MORE

November 2nd, 2012 by dave dorsey

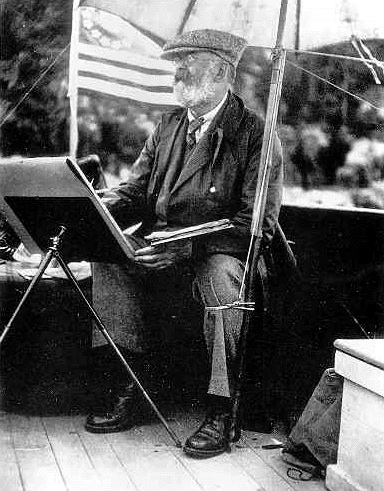

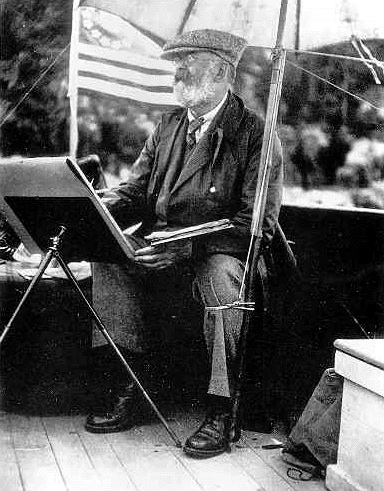

Love the umbrella tied to Sargent’s leg

“A portrait is a painting with something wrong with the mouth.” –John Singer Sargent

November 1st, 2012 by dave dorsey

Morning Light, oil on linen

For a two-artist show that opened last night at Oxford Gallery, where I’m exhibiting 26 paintings, along with a lot of tremendous work by Brian O’Neill, I printed two catalogs, one for me and one for him. I wrote a brief introduction for it, in which I tried to distill as clearly and succinctly as I could, why I paint. I’ve done this a number of time over the past five years, when an artist statement has been solicited for one exhibit or another. This time, I felt as if I came closer than I have in the past:

Painting, for me, is a non-conceptual way of apprehending life. It’s a philosophical stance as much as an aesthetic pursuit. In the process of making a representation of something, the world becomes a part of me in a way that rational thinking can’t achieve. Painting requires me to pay dispassionate attention to the way things are without any motive other than to be aware of them and share that awareness through paint. For me, that kind of mindfulness is entirely different from knowledge and intelligence. Painting isn’t about thinking or knowing. It’s about seeing what’s there; nothing more, but when it works you see more than what’s there as well. A good painting offers the viewer, subconsciously, an holistic glimpse of the world, not conscious information about some small part of it. A painting can function the way the taste of the pastry dipped in tea functioned for the narrator of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. In other words, it can summon an entire world from a simple act of perception. That kind of apprehension can offer pleasure, if the work is good, but that isn’t the purpose. It offers a calm state of impartial awareness—a glimpse into the way things are, in a way not accessible to conscious thought—and that kind of attention isn’t something highly esteemed in this contentious contemporary world. In that sense, a painting is a kind of meditation, for the one who makes it and the one who looks at it.