October 5th, 2013 by dave dorsey

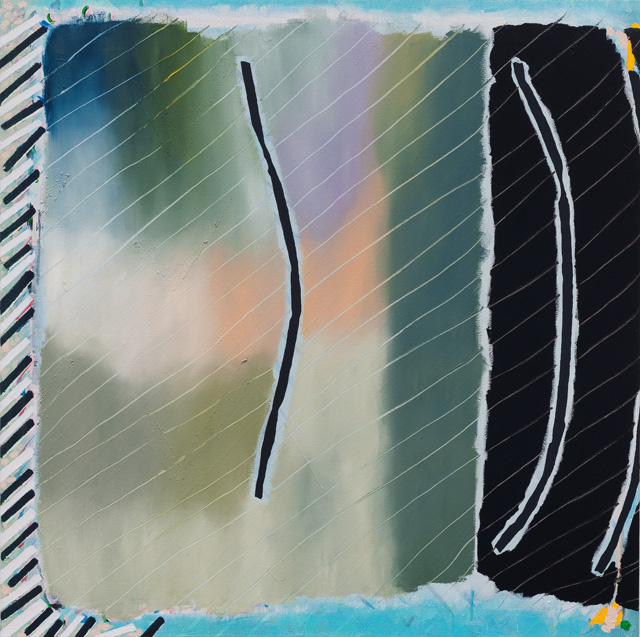

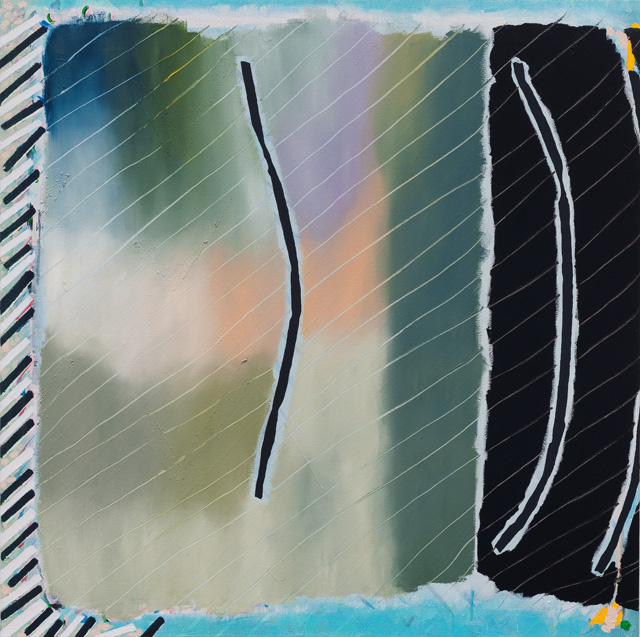

Allison Miller, “Wave” (2013), oil and acrylic/canvas, 36 x 36

I see a narrow depth of field, and therefore a background completely out of focus, glimpsed through rain, as my windshield wipers hit their apex, and I miss mine while steering through the turn. But I could be dreaming all that up. Definitely going to see this show when I’m back in the city this weekend.

From Hyperallergic:

The recent show further convinced me that Miller — who refuses to make work that is stylish, seductive, charming, nostalgic, retro, ironic or hip — is up to something. It is not that we wouldn’t recognize a Miller painting as such, it’s that she refuses to give her work a look. And in order to do this, and to keep everything in play while working on a painting, she seems to understand the necessity of exploring a territory that hasn’t been colonized by discourse, that hasn’t been snatched up and packaged by critics and theorists as the latest example of postmodern capital. I am further impressed by the fact that she refuses to affix a spiel to her work. I become distrustful when the artist resorts to a verbal component to deliver the enlightenment. –John Yau

So refreshing to read all of those sentences. I may post that somewhere as a manifesto, even though I fear I may give the appearance of violating much of it myself in the coming months. Doh. I actually have an idea for my solo show in May–until now I had hoped, as a painter, I possessed a mind so fine no idea could violate it. Apparently not. I pray I will recover from this after a spot of rest, once I’ve gotten it out of my system.

October 4th, 2013 by dave dorsey

Tryin’ real hard to be the shepherd in Chelsea

As I headed down 10th Ave. a couple weeks ago, I saw, for the first time, the at-first-glance bucolic installation of sculptured sheep by Fancois-Xavier Lalanne, where once I would have seen lines of cabs stretched into the avenue, waiting for gas. Paul Kasmin and real estate developer Michael Shvo have turned what was a Lukoil gas station into Getty Station, an outdoor gallery, complete with white fence, fake rolling pasture, and a soothing herd of sheep. It isn’t the first time the station has been used to exhibit art, but in the past, the gas kept flowing. The name is a nice turn: suggesting both the petroleum and the art associated with the Getty brand. Also nice: gas prices on the vertical sign have been replaced with the show’s opening and closing dates. A dignified gallery minion guarded the art and handed out leaflets about the show. The gas station’s metamorphosis has gotten a lot of publicity—it’s friendly, funny, a natural target for cell phone photographers. It’s nicer to walk past this site now than it was a month ago when overheated cabs clogged the sidewalk and street. They exhaled a bomb of exhaust that cloaked the entire corner. But they were there because we needed them, and they needed that gas station. It was a handy stop for people in the neighborhood who wanted a lift and income-sustaining for the drivers. (Kasmin told the Wall Street Journal that many have asked him, “Where can I catch a cab now?” Gosh, I don’t know. By walking a couple blocks and looking for the glowing number on the roof, maybe . . . )

My reaction to the change was mixed. Two weeks ago, as I walked through once-familiar areas of West Chelsea, I saw one example after another of a real estate boom. Across from the building that houses Viridian Artists and many other galleries, and which serves as home base for me, a large complex of “affordable housing” has been going up for months. Now, on the corner of 10th and 28th, where we used to buy sandwiches, Diet Cokes and an occasional beer, our friendly bodega was gone, and the site was locked down with steel shutters. I was told residences are going to be built there as well, and developers have pushed the little shop a block north to 29th. All of this would be encouraging, if I hadn’t lived through 2008 and witnessed the fallout of the real estate debacle ever since. When I stood at the edge of the pretend picket fence at Getty Station, all I could think about was the Wal-Mart syndrome—big money coming into an area and snuffing little enterprises on Main Street. Only in this case it’s big art money shutting down what appeared to be a small, thriving franchise serving a vital need for cab drivers hustling to make a living. The sheep are pleasant, but no one needs them. That gas station was alive, and small businesses exhibiting that station’s healthy vital signs are all that will turn the current economy around. Walking through so many galleries in Chelsea, as I do whenever I come to town, it already feels like walking through a string of high-end car dealerships, where the price tags are so out of reach for nearly anyone but the ultra-rich, you feel as if you’re peering through someone’s window into a lavish dinner party. Every time I walked past the old gas station, it was nice to see a little hint of how most people scrape together enough to pay the bills and keep a car running. It was a quick little sniff of reality on my way between the clean, filtered air of one white cube and the next. Those industrious cab drivers getting their tanks filled at the old Lukoil station were the sort of mudders who keep the American horse race alive. This installation of artificial sheep was cute, family-friendly, amusing and cheerful, but it depressed the hell out of me. I looked at the gallery attendant and shook my head, with a half-smile, and said, “Chelsea.” He nodded and smiled right back in exactly the same way, and said “Yup”, and then handed someone else one of his leaflets. I could have just said, “America.”

October 3rd, 2013 by dave dorsey

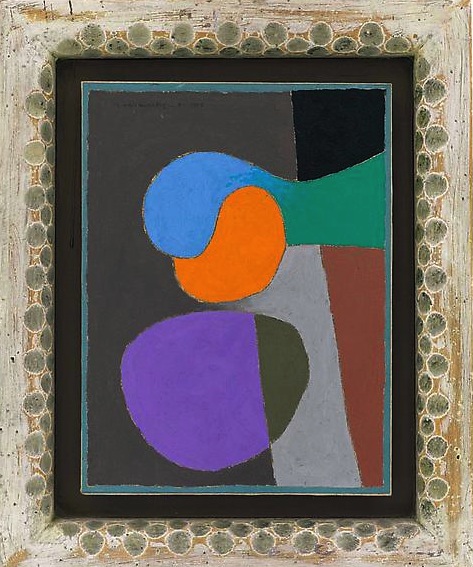

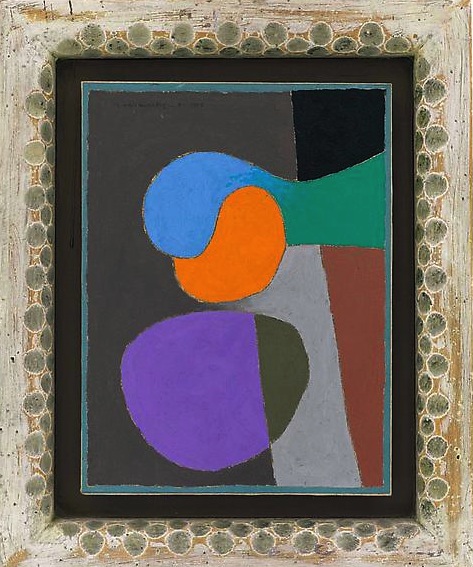

Frederick Hammersley, Got Is Love, 17.5″ x 14.5″

Until a couple weeks ago, I’d never been in the back room at Ameringer McEnery and Yohe. For another week or so, that semi-hidden room in back is full of Frederick Hammersley. (I had no idea the gallery had this third exhibit space, more or less concealed behind the desk. Evidence of slippage in my powers of observation. Doh.) It’s another taste of perfection, two years after their last Hammersley show (was it that long ago? you see my point about slippage . . . ), and though it isn’t quite as dazzling as the previous selection, it’s a pleasure. All the qualities that won me over before are in evidence again: the color harmonies, the tension between the organic abstracts and the geometric ones, the playful puns in the title. Got Is Love, for example, above. As a noun, it’s German for God, but it’s a verb for something else entirely, serving as a nice little commentary on American consumerism and plain old avarice. You love what you own. Is that a sales pitch, disguised as a title? Artists have to eat, contrary to common lore. Hey, cigarettes and Pernod are expensive too, for that matter. So if he’s saying love me, buy me: maybe that title isn’t so acerbic, after all. As with Hodgkins, the frame is integral to the painting and gives it even more presence as a three-dimensional object you look at rather than see through. In these paintings, as well as the minimal stripes from Gene Davis that dominate the gallery as the main event, you see the evidence of the unreliable human hand everywhere, unable to hew perfectly to any line, curved or straight, if only you get close enough to see how things meander a bit. In both cases, the wavering edges open up a world of feeling where you might first just see a cool and calculated exercise. The edge always striving to get back to where it belongs, as we all do in life, for better or worse.

October 2nd, 2013 by dave dorsey

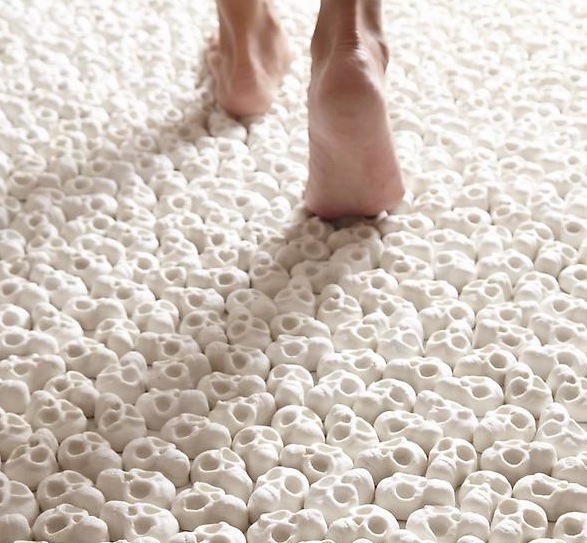

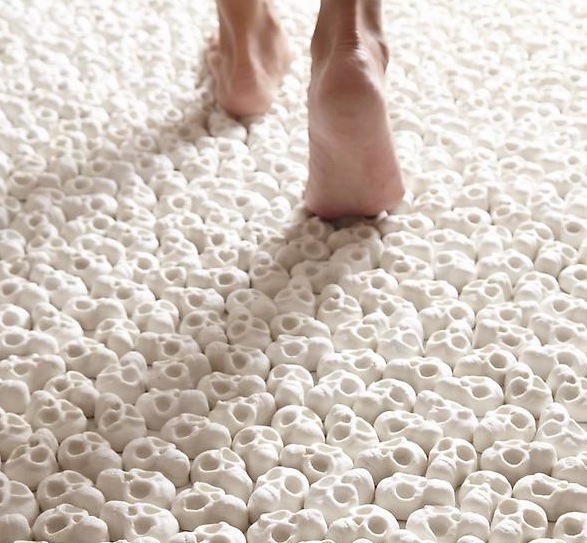

Skull installation in Singapore

I was hiking a few days ago through Mendon Ponds Park with my brother, and the subject of my skull paintings came up. Like many people, I think he assumed I’d developed a slight, morbid side-interest in death. I tried to explain that skulls go back centuries as a primary subject in vanitas still lifes. A skull painting isn’t a nice Goth fashion statement, or declaration of allegiance to the occult, or a logo for an Ivy League secret society, or an initiation into the Sons of Anarchy Painting Guild. Skull paintings were, and are, a reminder of what matters most in life: you may die at any time, so live accordingly. Every moment counts. Awareness of life’s brevity helps reveal how meaningless most pleasures are. Of course, as time runs out, you might also go on one sort of binge or another, but that’s simply testimony to how a vanitas paintings test of the viewer’s character. What are you going to do with whatever time remains? Vanitas painters themselves don’t always pass the test. They like to sneak into their paintings delightful but suitably evanescent sources of “meaningless” pleasure, thus giving themselves and their patrons an excuse to revel in those pleasures while feeling righteous about how brief they are. Barkeep, I’ve just contemplated death for fifteen seconds, make it a double. I’ve earned it. The vanitas tradition is certainly alive in Singapore where Nino Sarabutra has covered a gallery’s floor with 10,000 tiny skulls. I’m not sure if visitors are required to go barefoot, as it would appear in the photograph, but they ought to be. On one wall hangs a painting with the words: What Will You Leave Behind? Nothing morbid about this at all: it’s a question at the heart of any serious philosophical or spiritual attitude toward life. Nota bene: skulls can actually be beautiful in their own way, like old bleached objects washed up on a beach, as complex and full of curving, pitted forms as difficult to paint as a fading white flower. Our bones are like driftwood.

Now that’s the spirit . . .

October 1st, 2013 by dave dorsey

There is no love of truth without an unconditional acceptance of death. Everything which is threatened by time secretes falsehood in order not to die–and in direct proportion to the danger of death.

—Gravity and Grace, Simone Weil