Archive for January, 2014

January 30th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Breezeway, Ray Hassard

My favorite painting in the current two-person show at Oxford Gallery, looks both effortless and masterful. I love the way the pickup’s two tail lights vary in terms of the color’s saturation, which somehow looks entirely realistic and yet may just be an artifact of Hassard’s confident brushwork. Or the sun is hitting one directly and not the other. I’m guessing that’s a riding lawnmower in the foreground, shaded, under the arch, but it doesn’t matter what it is. Identifiable or not, it’s perfect. He’s one of the best pastel artists in the country, and most of the work on exhibit here is pastel, but he’s just as good with oil. Also in the show are Patricia Tribestone’s intensely colorful still lifes. Coming next month to Oxford: two artists I love in a three-man show: Rick Harrington and Matt Klos.

January 28th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Billy, the Magical Dog, in Los Angeles

This is an interesting Boston Review article that not only buries the lede, but obscures its thesis a bit by talking in circles around it. The core of it is the notion that dogs can teach us to eliminate the boundary between physical and mental through a different order of attentiveness and “obedience” to what’s actually happening around them. In other words, dogs are models of mindfulness–which never gets said in quite that way. The easier and more attention-getting point it keeps making is that dogs aren’t people–since most of us mistakenly treat them as if they were. By anthropomorphizing them, we diminish their greatest virtues and so on. The real point of the article is that people aren’t canine enough. People should strive to be more like dogs:

Dogs live on the track between the mental and the physical and seem to tease out a near-mystical disintegration of the bounds between them. Their knowing has everything to do with perception, an unprecedented attentiveness that unleashes another kind of intelligibility beyond the world of the human.

Unleashes. (That must have been too tough to resist.) “Another kind of intelligibility” comes and goes here, but that phrase made me stop and smile. “A knowing that has everything to do with perception,” not reasoning or conceptual thought, is what, for me, painting is all about. The ideas, the concepts, the implications of a painting beyond what perception alone conveys (and the point in this article is that perception alone can convey a world of immediate understanding and reaction that doesn’t require thought) these chimera can attach themselves after the fact, even with a purely perceptual painting, yet for me that’s the proper order. First the painting; then the idea. I’d like to think that Duchamp’s Fountain happened at the moment when he found himself involuntarily admiring the curving forms of a urinal, despite himself, and then probably realizing that a sculptor could have made it, and exhibited it, and then . . . well, Pop art followed with all of its preconceived ironies and poses, generating the flood of work it has produced. Yet it began with a simple perception, an awareness of how difficult it can be to differentiate between life and art. And even that thought was after the fact of the simple perception of beauty in the forms of something Duchamp was conditioned (by thought) to see as nearly the exact opposite of art, the lowest object imaginable, because he knew its purpose. So he turned his perception into a highbrow joke. It really is a fountain, and the more you think of it as a fountain, the more laughs you’ll get out of Duchamp’s humor, yet the more you think, the further you get from the original, unsullied perception of the formal qualities in that porcelain object that set in motion the whole notion of exhibiting a urinal. What has bothered me about art, at least since Duchamp, is how perception, which is the heart of visual art, has so often been subordinated to the ideas that arise around it, or that, at its worst, art becomes merely an illustration for an idea, a visualization of a thought. The ideas should be at the end of the process of struggling with the formal challenges of a medium, not at the start, in my humble opinion. It’s the pursuit of “another kind of intelligibility” unavailable to the calculating, reasoning mind: Duchamp had that at the moment he paused to keep looking at the urinal . . . and then his calculating mind took over and we’re back in the world of commonplace intelligibility, and a “stance” about art and the art world in general, implied in the humor and scandal of exhibiting a urinal as a work of art.

Painting can dissolve the boundary between mental and physical and produce, as it happens, a different kind of exuberance about life that has everything to do with having more awareness than opinions about it. So, all of this only confirms what my wife has often thought: yes, I’m a dog.

January 26th, 2014 by dave dorsey

My cow skull

A little Zen pun up above to brighten your day. Every morning in my studio, this cow skull that Susan Sills kindly gave me, sits on that stool and doesn’t actually say Mu, like Joshu, but it does whisper tempis fugit. Always showing off its Latin. I just say, thanks Boss. (Which is close enough to the Latin for “cow.” Bos.) I know all about it at my age. Time flies. But I get more painting done when I’m reminded.

January 24th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Edwin Dickinson, Snow on Quai, Memorial Art Gallery

One of Dickinson’s premier coup paintings, an exhilarating find for me, at the Memorial Art Gallery, where I took this shot yesterday.

January 19th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Art can show you what’s right there in front of you, but you don’t really see it, you aren’t fully aware of it, until art represents it. This passage from Wittgenstein is confusingly worded, but I’m sure he meant “imagine a curtain goes up and you see yourself, walking up and down, lighting a cigarette, sitting down. . . ”

Let us imagine a theatre; the curtain goes up and we see a man alone in a room, walking up and down, lighting a cigarette, sitting down, etc. so that suddenly we are observing a human being from outside in a way that ordinarily we can never observe ourselves; it would be like watching a chapter of a biography with our own eyes — surely this would be uncanny and wonderful at the same time. We should be observing something more wonderful than anything a playwright could arrange to be acted or spoken on the stage: life itself.

But then we do see this every day without its making the slightest impression on us!

–Wittgenstein

January 15th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Self, Valerii Klymchuk

In the current solo show at Viridian Artists, you can get a sample of work from one of our youngest members, who immigrated from Russia only a few years ago: Valerii Klymchuk. Many of his images make me wonder if he believes, as Heraclitus did, that the world is made of fire, and his sense of color is intense, personal and lyrical. He’s a brilliant young man, who got into a program at Columbia University to study big data, but couldn’t afford the tuition. He has the look of a young man out of a Dostoevsky novel, or one of those contemporary Russian Orthodox monks in the book Everyday Saints. Maybe if he sells one or two paintings, at the prices he’s asking, which have always made me smile, he can get his coursework done at Columbia. He has a bit of that Warhol impishness about him: half the time, I can’t tell if he’s putting us on or if he’s dead serious, but in these answers there’s very little irony. He hasn’t been painting long, but he has a kind of courage to do anything that occurs to him, in his work, that would rarely occur to a career-minded painter as an option these days. I sent him a few questions, and rather than try to filter his thinking, I’m passing most of it along as he sent it to me. He sounds Russian, even in his writing:

You took up painting without studying it in school right?

I just started doing art without any previous studying. It happened spontaneously, during one of the hardest periods of my life when I was desperate to find meaning in my life, struggling to find my own place in this world. I was introduced to painting by a friend in New Jersey. He hosts painting sessions at his house, where he and his friends sit down on the floor painting.

Before that day, I never considered myself an artist, and I never thought I had artistic talent. Just the opposite—I thought that I had no talent in painting whatsoever. My sister could paint, and I knew that I was good in mathematics and sciences, but I thought that painting was something absolutely foreign to me. I never had any tendencies to express myself in painting before.

Only when I painted for the first time at my friend’s house . . . was I surprised to MORE

January 14th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Betty Woodman, June in Italy, detail, 2001

glazed earthenware, epoxy resin, lacquer and paint

Apropos of nothing, a small sample of work from our greatest living colorist, Betty Woodman, who does ceramics which, for me, are really three-dimensional paintings that put Stella’s constructions to shame. The tragic brilliance of her daughter’s photography may have eclipsed Woodman’s Matisse-class talent with color, but her work is a humbling joy, every time I return to it.

January 12th, 2014 by dave dorsey

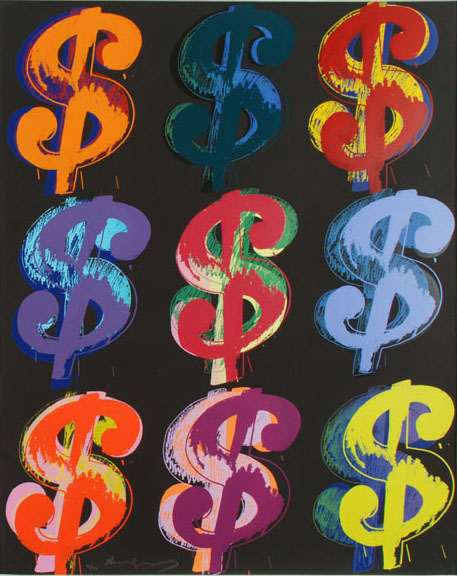

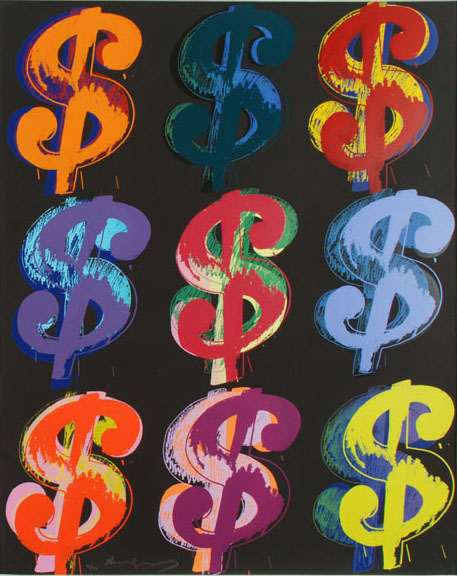

Why it becomes harder and harder to make an ordinary living from painting. (As if it was ever a sensible career path for the merely talented.) Robert Frank in today’s NYTimes: “(Income) inequality in the United States has been increasing sharply for more than four decades and shows no signs of retreat. In varying degrees, it’s been the same pattern in other countries. The economy has been changing, and new forces are causing inequality to feed on itself.

One is that the higher incomes of top earners have been shifting consumer demand in favor of goods whose value stems from the talents of other top earners. Because the wealthy have just about every possession anyone might need, they tend to spend their extra income in pursuit of something special. And, often, what makes goods special today is that they’re produced by people or organizations whose talents can’t be duplicated easily. Wealthy people don’t choose just any architects, artists, lawyers, plastic surgeons, heart specialists or cosmetic dentists. They seek out the best, and the most expensive, practitioners in each category. The information revolution has greatly increased their ability to find those practitioners and transact with them. So as the rich get richer, the talented people they patronize get richer, too. Their spending, in turn, increases the incomes of other elite practitioners, and so on.”

January 10th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Eric Hollenbeck, craftsman

This short video about a woodworker captures one of the most central reasons I paint: to make something carefully and skillfully by hand.

January 8th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Close at work

“Persistence: we call it getting to know the Muse.”

- Writer E. B. White: “A writer who waits for ideal conditions under which to work will die without putting a word on paper.”

- Painter Chuck Close: “Inspiration is for amateurs–the rest of us just show up and get to work.”

- Composer Peter Tchaikovsky: “A self-respecting artist must not fold his hands on the pretext that he is not in the mood.”

—Fast Company

January 6th, 2014 by dave dorsey

Dragon, by J.R.R. Tolkien

What amazes me is that Tolkien actually had time to produce the quantity of art he did, with such assiduous attention to detail. Love this dragon, a sort of Celtic ornamental design. It’s about as far as a dragon can be from the one in the theaters at the moment, which reminded me of the badass winged lizard in Reign of Fire. Which is a beast the evil corporation in Alien would want to weaponize. Am I watching too many movies? No. Yes.

Most of the Tolkien art at Brain Pickings remind me of Jung’s artwork. The illustration, below, of “Undertenishness”–the spiritual state of being younger than ten years old (sounds like a German word–is like a poem. A path toward the horizon that’s actually moth-ride to somewhere else. If you don’t mind riding a moth. Hey, Gandalf booked a flight with a moth, come to think of it. (His illustration of “Grownupishness” includes the caption: Sightless, Blind, Well-Wrapped Up.)

Undertenishness, by J.R.R. Tolkien

January 2nd, 2014 by dave dorsey

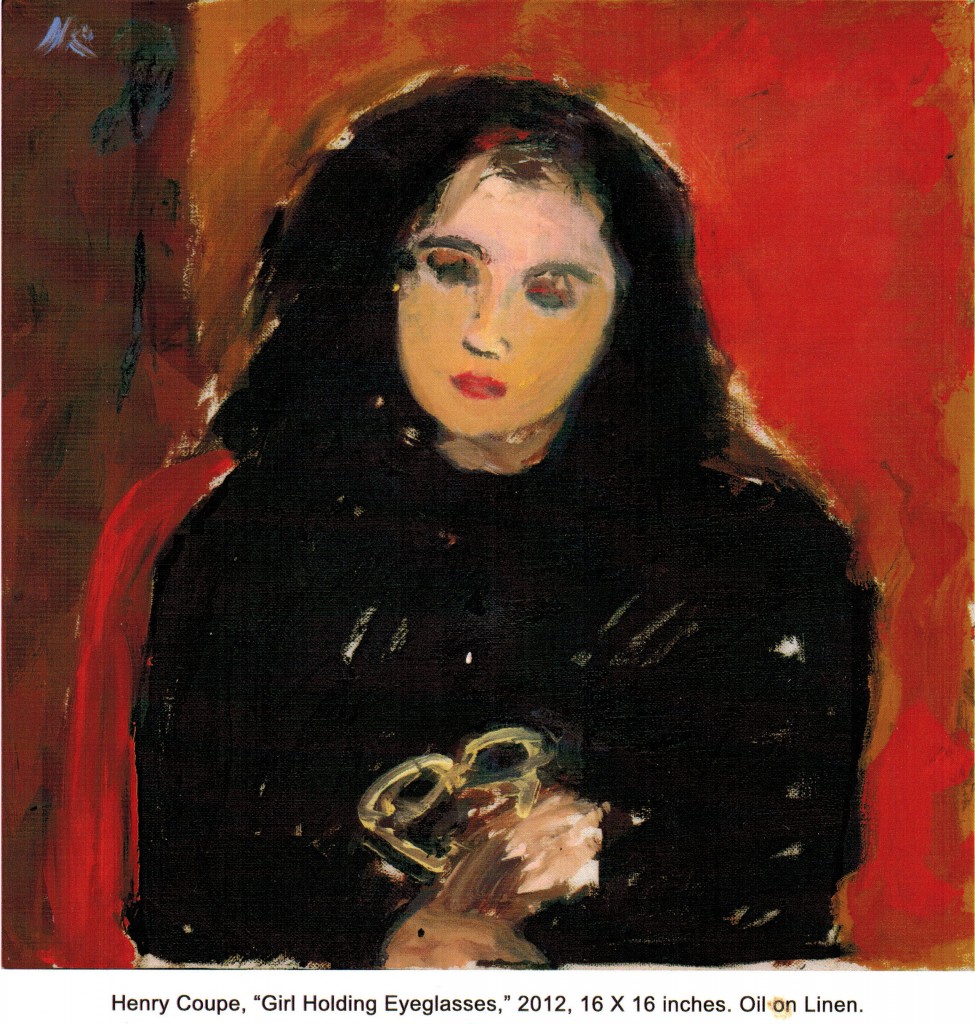

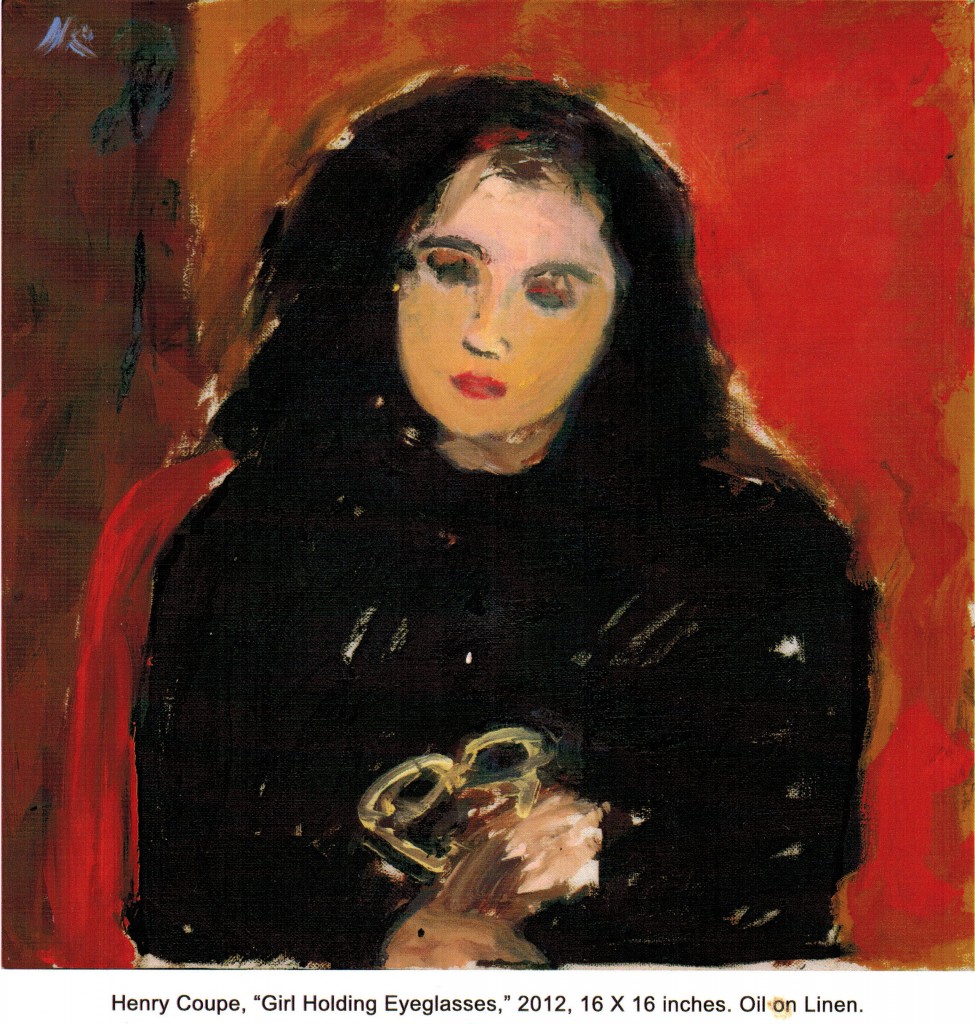

When I can carve out the time soon, I’m going to write about Henry Coupe and his oils. Coupe joined Viridian Artists late last year, and we had several of his paintings sitting along the countertop behind the desk. As I was talking to our gallery sitter, I kept glancing at the paintings, wondering where they’d come from. After about an hour, I finally spoke up and was told that he’s an 89-year-old artist in Utica who has been painting and exhibiting since the 60s. The more I looked, the more I liked. So on my last drive to the city, to help hang the current show, I stopped in Utica for a few hours and met with his wife, Ann, who told me Henry entered a nursing home in the past year, thanks to a life-threatening accident when he was being tested at a local hospital. I got a chance to see somewhere in the range of three dozen of his paintings there at his house, and we visited the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, where I studied print-making when I lived in Utica and worked as a reporter at the Observer-Dispatch in the 80s. Anyway, much more when I have the time to write at length about his tremendous work.