Archive for August, 2015

August 27th, 2015 by dave dorsey

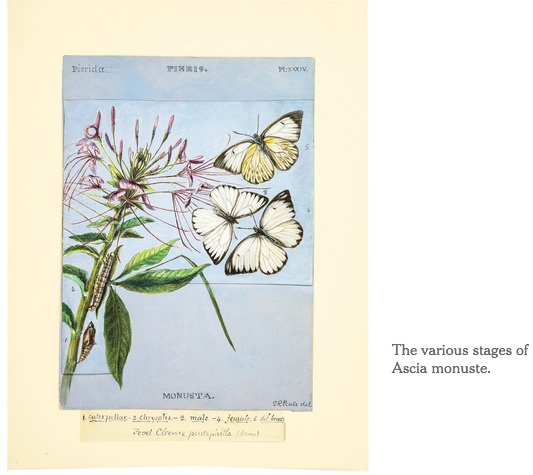

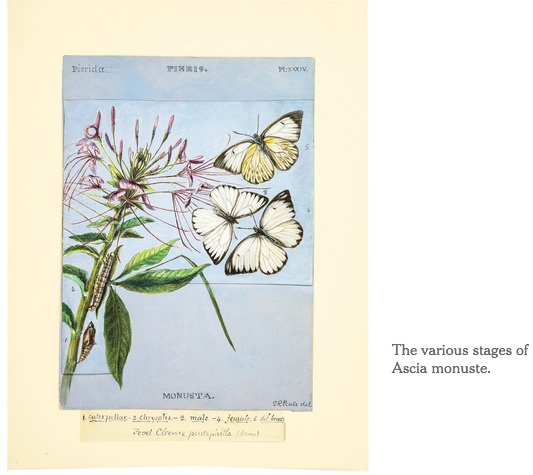

A New York Times review of a book about butterflies and moths, unfinished and never published in its author’s life, sounds as if it’s worth a look. I see there will be illustrations of leaves in it. I’ve been laboring with the job of rendering peony leaves in oil paint over the past couple weeks–it might do my morale good to see how someone else succeeded or fell short in the effort. But I’m interested in this fellow’s project on its own merits. A few days after my wife and I moved into our little A-frame-like gingerbread house in Utica, New York, back in the 80s, we found a cecropia moth slowly fanning its wings on a rock in the little overgrown garden left behind by the previous owners. It seemed more animal than insect. With wings spread, it was as large as my hand. The symmetrical patterns in those scaled appendages, intricate and abstract, looked like eyes or planets. And this, in turn, reminds me that I have yet to write a full response to the fantastic retrospective of Emmet Gowin’s photographs at the Morgan–this book of lepidoptera coincidentally echoes Gowin’s humble, obsessive two-decade photographic pursuit of butterflies and moths in South America.

The book described below, The Butterflies of North America, includes the drawings by a fellow artist/observer, Titian Peale (who seemed to be named after two earlier artists.) Anyone who undertakes any artistic project that stretches over decades is automatically interesting, yet the names of his winged insects alone are a treat:

. . . you’ll discover the Mexican dartwhite and the Pacific orangetip, the yucca and the duskywing skipper, the coontie hairstreak and the sunset daggerwing, the stinky leafwing and the patch checkerspot — not to mention the Eastern comma and the mourning cloak. There are moths here, too: the yellow-necked prominent, the white-marked tussock, the satellite Sphinx and the snout.

The book, unfinished and unpublished when Peale died in 1885, represents more than 50 years of work. The manuscript ended up in the rare book collection of the American Museum of Natural History, where it somehow languished after it was donated by a family member in 1916. All of Peale’s artwork and some of his field notes from the manuscript are being published next week as “The Butterflies of North America: Titian Peale’s Lost Manuscript.”

Peale, who spent much of his life as an assistant examiner with the United States Patent Office, could never have lived up to the original title; there are, after all, several thousand species of Lepidoptera in North America. But what he did leave us is revelation enough.

“Butterflies” features more than 200 works of art — in gouache, watercolor, ink and pencil — that through Peale’s sharp but sensuous eye show the life cycle of moths and butterflies, from egg to caterpillar to pupa to winged adult. These striking illustrations are complemented by notes, studies and sketches in Peale’s hand from his field books.

Peale “considered scientific description and graphic representation entirely commensurate and complementary modes of attention to the natural world,” the art historian Kenneth Haltman writes in the book’s biographical essay.

Each caterpillar, often paired with its preferred food, is precisely drafted. Peale takes clear pleasure in depicting each foot, bristle and segment in tiny strokes. “Walking, bending, and inching up branches, Peale’s caterpillars are a tour de force of observational art,” Tom Baione, director of the museum’s research library, writes in the introduction to the section.

We may marvel at the sheer biological persistence of the 17-year locust, but consider: Titian Peale’s lost illustrations are finally seeing the light of day after a metamorphosis lasting nearly 200 years.

August 18th, 2015 by dave dorsey

New brushes from Dick Blick

Hope and confidence both. Can’t buy me love. Can’t buy me faith. But I can buy a little accessory to hope. Is there anything more like a fresh start than a set of new brushes? For a painting I started in May, granted, but I’m getting that campfire in the gut while working on it.

August 16th, 2015 by dave dorsey

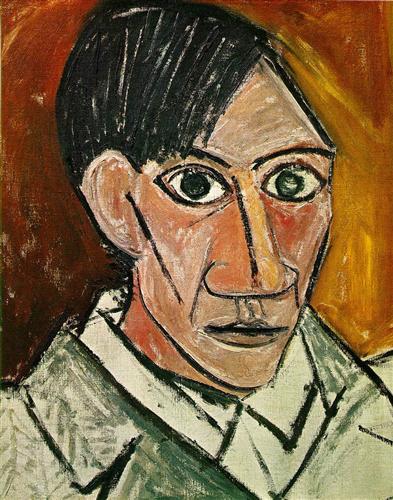

I think I might become absorbed with my tomatoes in tough times as well. The divide between the work and the life is something a lot of critics can’t get past. The personal life is inconsequential compared to the achievement. From The Paris Review:

INTERVIEWER

What happened to your biography of Picasso?

McCULLOUGH

I quit. I didn’t like him. I thought I would do him as an event, the Krakatoa of art. He changed the way we see; he changed the imagery of our time. But then I realized that strictly in terms of what would work for me, his wasn’t an interesting life.

There’s an old writer’s adage: keep your hero in trouble. With Truman, for instance, that’s never a problem, because he’s always in trouble. Picasso, on the other hand, was immediately successful.

Except for his painting and his love affairs, he lived a prosaic life. He was a communist, which presumably would be somewhat interesting, but during the Nazi occupation of Paris he seems to have been mainly concerned with his tomato plants.

And then his son chains himself to the gate outside trying to get his father’s attention; Picasso calls the police to have him taken away. He was an awful man.

I don’t think you have to love your subject—initially you shouldn’t—but it’s like picking a roommate. After all you’re going to be with that person every day, maybe for years, and why subject yourself to someone you have no respect for or outright don’t like?

August 14th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Dan Witz, Agnostic Front Circle Pit, 48″ x 82″, detail, oil/digital media, Jonathan Levine

Pieter Bruegel, Peasant Dance, detail

August 12th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Piet Mondrian, Red Dahlia, 1907, (detail), Opaque and transparent watercolor over graphite on paper. 12 7/16 x 9 7/8 inches Morgan Library

I discovered this watercolor of a dahlia by Piet Mondrian in the Morgan Library’s current retrospective of Emmet Gowin’s photography, a small show that was both astonishing and humbling when I ducked in to see it on my way to JFK on Friday. It’s so great I almost didn’t want to sully it with words, though I’m sure I will soon. Instead, I wanted to stay and study it for a few days, make myself at home, but I had that late flight back to Rochester at Terminal 5. The catalog lists everything on exhibit, but doesn’t offer images of more than a fourth or a third of it, and I was disappointed not to be able to revisit, in the catalog, many of the startling and powerful pieces, reaching back centuries, from the Morgan’s vault that Gowin chose to include in the exhibit. Since I’ve been growing dahlias for nearly a decade and painted many of them, this little revelation surprised and pleased me, especially since it’s so well done, but also because it demonstrated how artists can’t really stick to one thing for long, and how polarities can energize their work.

I had no idea that, while he was realizing his identity in his famous primary-colored grids, Mondrian continued to draw flowers, work that represented the exact opposite of his oils, in formal terms. Nothing could be further from Mondrian’s career-making grids than this dahlia, yet maybe these flowers are precisely what sustained his investigation of the spare music he found in rectangles and squares. (Frederick Hammersley’s dialectic of working in both geometric and organic shapes comes to mind.) Gowin shifted gears a number of times himself and was intensely absorbed by opposing, contrary states: light and dark, harrowing desolation and domestic rapture, butterflies from the rain forest and craters from the wastelands of nuclear testing. I will save for a future post what he communicated to me with these images toggling between garden and gehenna (to adopt the Biblical mythology Gowin absorbed young and then deployed as a foundation for his mature artistic vision and for this show.) His deep immersion in William Blake’s writing and visual art is what drew me to the show, and he’s a worthy heir to Blake in his own photography, an earlier genius who drew from Gnosticism as the foundation for a deeply original vision. Two of Blake’s best, from his illustrations for the Book of Job–both of which I saw previously, in an earlier show at the Morgan–are included alongside Gowin’s photographs.

Gowin is a great soul, and this exhibit is a profound experience, a major discovery of the breadth and depth of his sensibility, and it’s impossible to do justice to it in a blog post. But maybe, if I can respond to this show the way I’d like in a little while, I can encourage a few to see what he’s done, because of the quality of work Gowin produced himself, but also because everything in the show appears fresh and new in the context of this photographer’s long and slow curatorial excavation of art from the Morgan’s permanent collection to pair with his own photography. As the curator of this show, Gowin has put together a visionary work of art itself–everything you see feels as if you’re glimpsing something for the first time. More often than not, it was literally my first look at the work. I felt regret simply pulling myself away from one image hanging on the wall in order to see what was mounted next to it. With the time available to me after a day’s working visit to the city, I picked the one exhibit that could not have been equaled (in the artist’s reverence, awe, decency and quiet authority) by anything else on view in New York City right now. Apparently, my luck continues to hold. And so does my mournful hope that quiet, deeply humble art, grounded in genuine wisdom and an affirmation of all human experience, can prevail. Gowin is a sage. Joseph Campbell would have loved this show.

August 10th, 2015 by dave dorsey

Hsin Wang, No. 24, pigment injet print. From I Love You Bedford, 294 Bedford Ave., Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Aug. 6-24. From the artist’s diary:

” eventually

everyone will

leave me.

I will leave

everyone.

everyone will

leave

everyone. “

August 8th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I like to watch. It’s one of the few things I have in common with Chauncey Gardner. (I’ll let you know if I ever walk on water. Still failing at this point.) A new service will allow me and others to eavesdrop on other artists as they work, and communicate with them as they do their work, though it’s hard to imagine why anyone would want to watch me in the studio. Maybe as a coffee break from the more emotionally taxing act of watching grass grow. It’s called Sywork, (Show Your Work), and it’s in beta at the moment and is mostly a medium for illustrators to get together and learn from one another. It’s an interesting idea though it sounds as if it consumes what I never have enough of–time. From an interview with the founder:

Today, a company called Sywork (shorthand for “Show Your Work”) launched its new live-streaming service for artists and illustrators. Ever wonder what the process is behind beautiful oil paintings? Comic books? Well now you can find out . . .

Each artist has their own channel, which you can subscribe to of course, and you’re notified when they’re live. A few of the illustrators I’ve watched have been heads down making things, with music bumping in the background. Much like Twitch, there’s a chatroom to the right, where people who are watching talk about what they’re seeing.

I spoke to one of Sywork’s founders, Marcelo Echeverria, about the site:

TC: How did you come up with the idea for Sywork?

ME: We are creators ourselves. We’re also big fans of games, movies and comics, and wanted to see our favorite creators livestreaming as they worked.

We were looking for a place where illustrators could show their process and realized that a lot of artists have the same problem. Artists we talked to were trying to find a place to live stream. They were using google hangouts, paid live streaming platforms or even gaming platforms like Twitch. But there wasn’t a place created specially for them.

We want Sywork to be a place where creators can engage with each other and fans, build their audience and make extra money doing it. There are thousands of people who want to watch artists work live. We went to Comic Con this year and saw how passionate people are about their favorite artists.

August 5th, 2015 by dave dorsey

I’m back from my wandering in New England and Canada, 1606 miles on two wheels with a duffel bag, back to the easel and the laptop, and I’m catching up on some DVR content after two weeks almost entirely devoid of TV viewing. I watched Kacey Musgraves open for Dale Watson, the “Antichrist of Country,” on Austin City Limits and in the quick interview following his performance he quoted John Lennon: “One’s originality comes from the inability to emulate your influences.” I loved that quote. It reminded me of how Van Gogh’s failure to be an Impressionist led him to become himself as a painter, as did Braque’s unfulfilled desire to be Cezanne. What seems like a limitation in technique or style can be exactly what lays the ground for authentic work, if you embrace it.

August 3rd, 2015 by dave dorsey

The Raft: All That You Can’t Leave Behind, Kevin Muente, Kentucky, oil on canvas, 41″ x 54″

From Manifest’s INPA 4.