Archive for July, 2016

July 26th, 2016 by dave dorsey

With this being, the artist, Being lights up for us most immediately and brightly. Why? Nietzsche does not explicitly say why; yet we can easily discover the reason. To be an artist is to be able to bring something forth. But to bring forth means to establish in Being something that does not yet exist. It is as though in bringing-forth we dwelled upon the coming to be of beings and could see there with utter clarity their essence.

Being an artist is a way of life.

__Heidegger’s lectures on Nietzsche (1936-40), Vol. 1

July 22nd, 2016 by dave dorsey

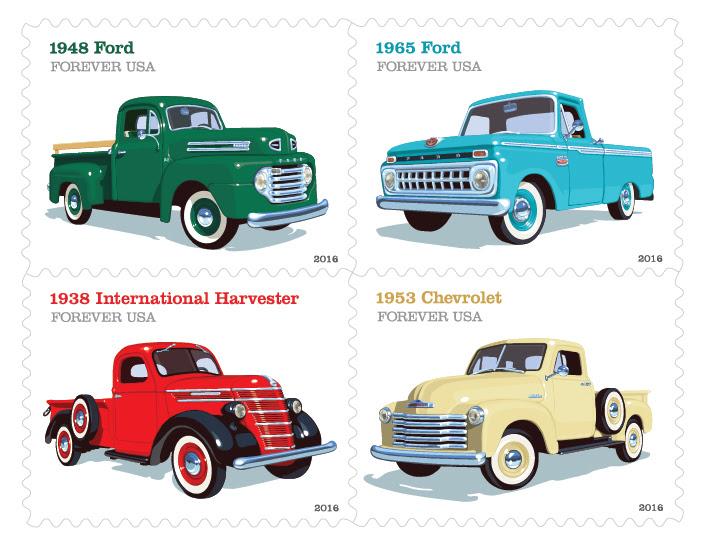

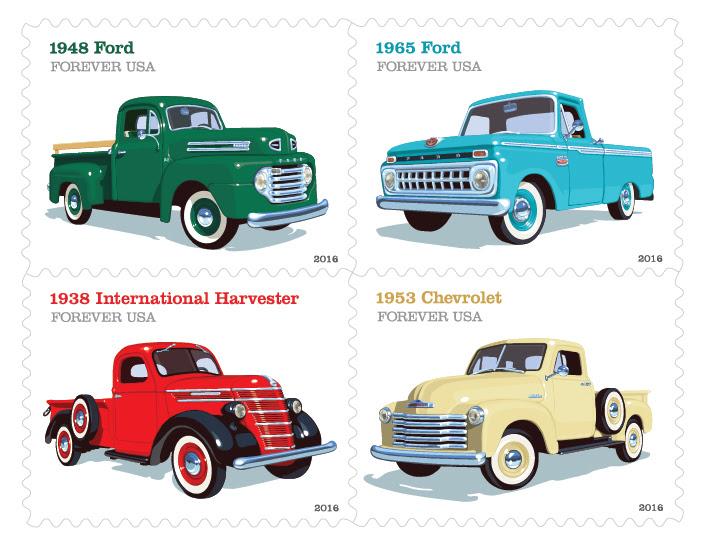

Long-time buddy of mine, Chris Lyons, designed these four stamps for the Postmaster General. He told me that his work underwent a rigorous vetting process, to make sure the designs were effective and suitable, and that he was forbidden from relying on photographs as a source for his images, presumably to prevent copyright violation issues. His own shots would have been fine. I would have recognized an easy write-off and a fun junket in a photo shoot at a classic car show in, say, Carmel-by-the-Sea. Instead, Chris relied on scale models, a few which I believe he still has in the trunk of his actual, current-model car. The only other stamp designer I know by name is Marge’s husband in the movie Fargo, Norm Gunderson. In the movie, Norm artwork made it onto only the three-cent stamp, while Chris’s work is forever.

July 21st, 2016 by dave dorsey

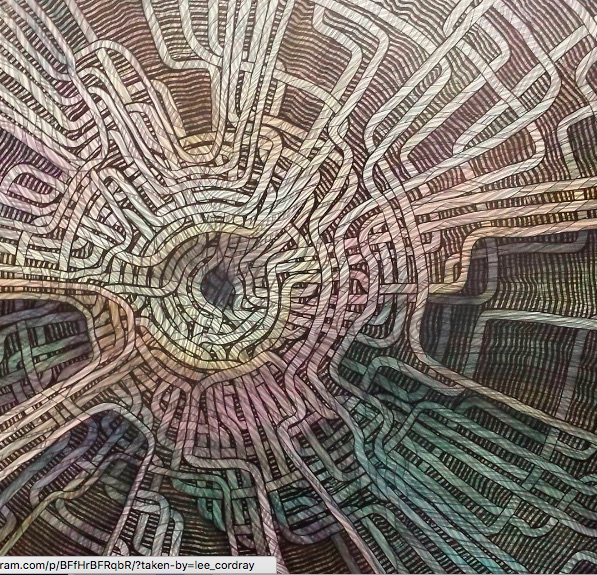

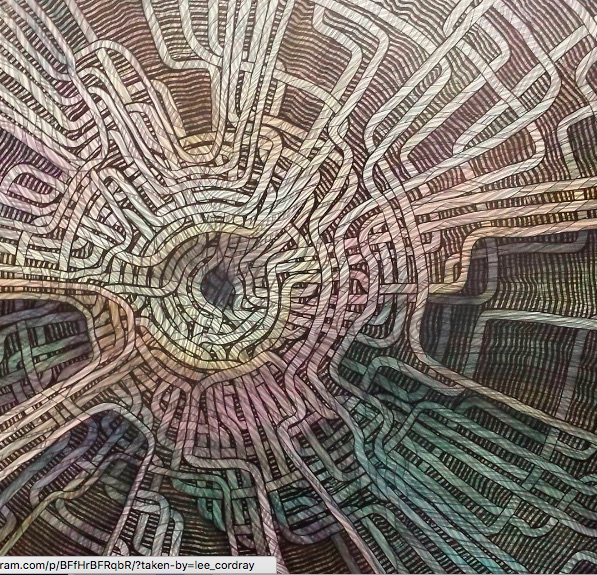

From his Instagram.

July 18th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Takeaway: Respect Vermeer above all. And do whatever they are saying can’t be done anymore. From Chuck Close profile today in the Times magazine:

Even as you slip forward a few years and he begins adding color in the early 1970s, you’ll find no painterly style on the canvas, no distinctive brushwork — namely because he had given up brushes to work with a paint sprayer, which he considered a homage to Vermeer. “I can figure out how any painting in the history of art got made, with the exception of Vermeer’s,” he told me. “It’s like a divine wind blew the pigment on.”

Remember that Close was making these portraits at a time of spectacular upheaval in American art, when many of his contemporaries were preoccupied with wild, experimental work — with artists like Walter de Maria, Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson moving into the desert, where they would trap lightning, build a mile-long city of black stone and extend a huge spiral walkway into the Great Salt Lake. Just a few years earlier, the prominent critic Clement Greenberg effectively banished the kind of work that Close was doing from the ranks of modern art. “With an advanced artist,” Greenberg wrote, “it’s now not possible to make a portrait.” So in the world that Close inhabited, his work presented a strange duality. In one sense, the decision to paint photographic portraiture was almost laughably conventional. In another, it was among the most defiant things a downtown artist could do . . .

July 15th, 2016 by dave dorsey

I was having an email conversation with a good friend (and a couple others, including my brother) on the need, or lack of it, for historical accuracy in movies based on actual events. My friend’s position was that art can do anything it likes, as long as it conveys eternal and absolute human values. I’ve been reading Heidegger’s later lectures over the past year—I’m going to offer much more of my thoughts on those in the near future, I hope—where the idea of “values,” comes under repeated assault, in interesting ways. Yet, as penetrating and surprisingly accessible as Heidegger is in these essays, I tend to agree with my friend, not Heidegger, that in the moral realm, certain things are unassailable and unchanging. (Heidegger’s interest was never ethics, which is why he’s compelling, but more on that later.) Yet, those eternal “values” or “truths” my friend advocates are like Kafka’s castle, partly visible from down here in the village, but its hard to find a permanent home in them–and often difficult to connect that realm with the complexity of human obligations down here on the street.

My friend’s position is that movies need to embody moral truth in order to be worthwhile, and any viewing time devoted to films of lesser quality is not just a waste of attention but destructive. TV should come with a surgeon general’s warning. I informed him that, right or not, he would be able to pry my vintage DVDs of The Simpsons from my fingers only when said fingers are cold and dead. (Actually I cited Rocky and Bullwinkle.) He was unmoved. But he insists, as always, that movies can be utterly unpleasant to watch—the equivalent of eating your broccoli—and yet be essential to the life of the mind. Last Year at Marienbad? Really? Dave Hickey became notorious as an articulate opponent of this view in his celebration of the essential need for beauty in art. His position, as I understand it, is: Give me pleasure or move along—because without it, I’m not going to pay attention to your precious truths. I second that. And I believe Hickey was suggesting that beauty keeps generating truth in different ways as time passes, for succeeding generations, all on its own, without a premeditated effort to adhere to some preconception of “truth” prior to its creation. Its creation becomes a source of unexpected truth, not an illustration of something already known. (This is actually closer to Heidegger’s outlook, I suspect.)

My friend insists that we ignore certain annoying or unpleasant expressions of truth in films at our peril. As much as I disagree with his general stance on this, and think that a movie ought to be engaging and at some level enjoyable to watch, no matter how uncompromisingly true it is, I wasn’t going to engage him on this. I’ve learned not to do that. Yet, along with Hickey, I think this attitude, in part, has made visual art the sort of isolated, segregated, boutique activity most people consider it to be now—a branch of the arts, in general, created only for the discerning, initiated elite while being irrelevant to most people’s lives. As I put it to my good friend: “My position on all this is to ask, if a tree falls in a forest and no one bothers to listen, does it matter whether or not it makes a sound?”

July 10th, 2016 by dave dorsey

Onion on a Carved Table, oil on linen

Jim and Ginny Hall’s Oxford Gallery has been selling a lot of my work over the past two years. When I got back from our visit to California this month, I found a check for this one waiting for me. He’d included it in the gallery’s summer show.

July 6th, 2016 by dave dorsey

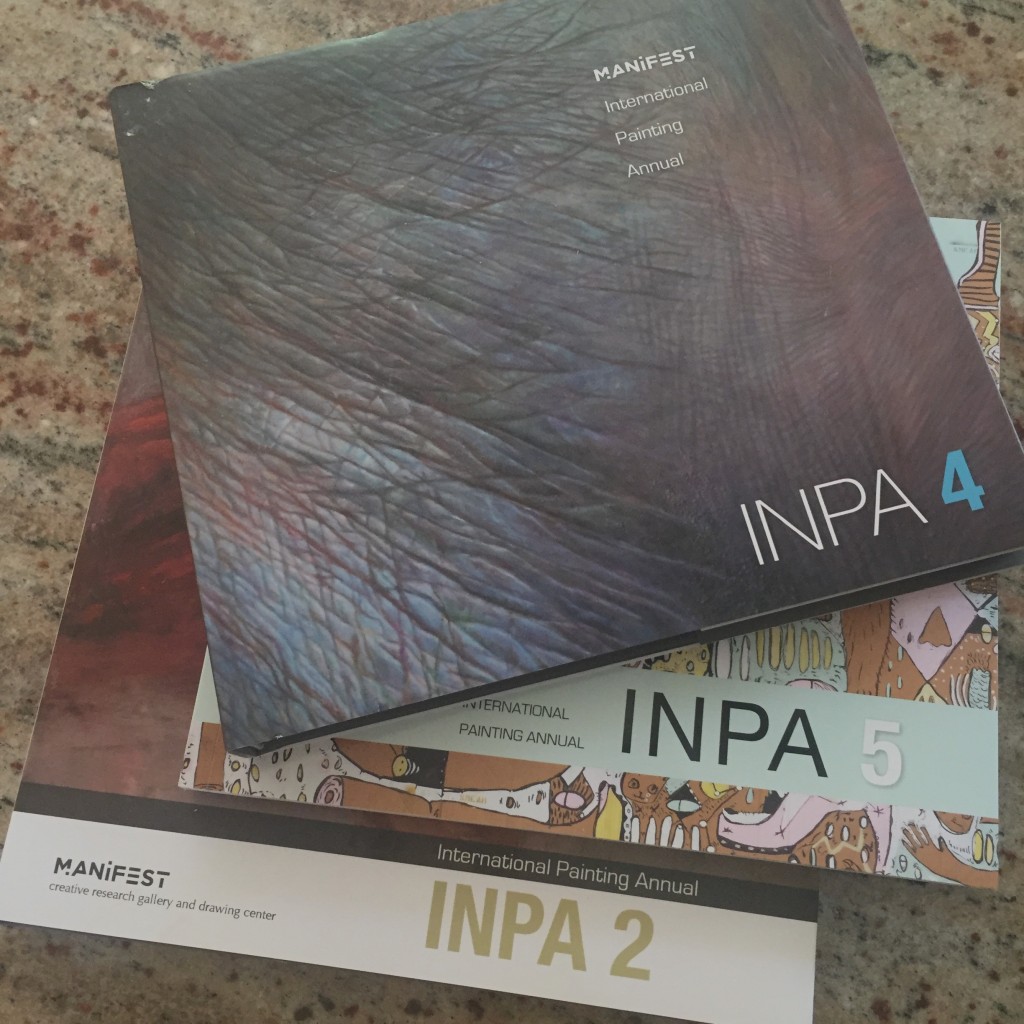

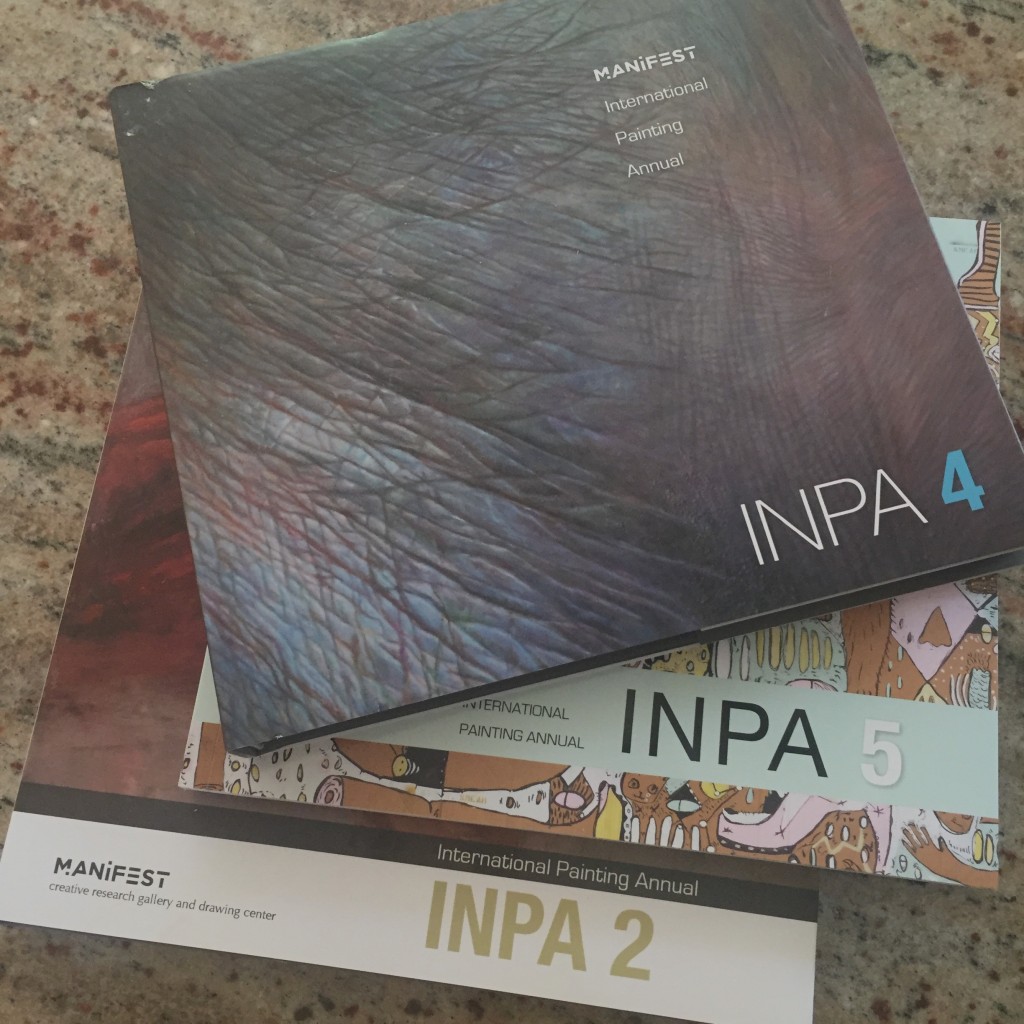

From Jason Franz at Manifest Gallery about one of the worthiest opportunities for artists who want to get their work seen:

It is the 7th INPA I’m writing about today…

If you have not already done so, I would like to encourage you to consider submitting your work to the 7th International Painting Annual which has the upcoming (final) deadline of July 24th.

As you may recall, within the past few years we doubled the cash awards for all three of our book projects—with each now offering a $1200 first prize. We do everything with our fellow artists in mind (we’re artists, students, and professors too!), and so we are very happy when our board of directors approves an increase in what we can give back. Believe me, we know that every little bit helps. (We also increased the Manifest Prize to $5000!).

Remember, our non-profit publications are undertaken in an effort to allow wider participation by artists from farther away since they do not require the physical work be available or shipped. The books also enable our otherwise gallery-bound exhibition program to reach a wider viewing audience because books can easily be shipped anywhere.

Many academic libraries collect our publications and college professors (perhaps many of you!) use our books in the classroom as prime examples of the diversity of types of works being made around the world by artists their students can relate to. The fact that we refresh this collection every year makes the resulting compendium even more valuable for everyone.

It is very important for you to know that your past participation does not hinder nor help your submission to this or future projects. As you surely know by now, Manifest’s juries are shuffled each project, and juries are ‘blind’ in that they are not aware of whose work they’re viewing. Your identity is not a criteria. That said, you’ve had success in the past, and this is a good sign that your work has what it takes to win approval through the Manifest jury process. That fact should be encouraging.

So, because we want this 7th volume to continue the series’ participation level and growth in quality and diversity of painting, I wanted to encourage you to submit your work, and to share the opportunity with others if you would.

You can get the details here: www.manifestgallery.org/inpa7

Please don’t hesitate to email me if you have any questions. And thanks again for being a part of Manifest’s history! I hope to see your work again soon.

Jason Franz

Executive Director