April 20th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Breakfast With Golden Raspberries, oil on linen, 22″ x 46″

I was pleased to learn that Breakfast with Golden Raspberries was invited to another exhibition, the Midyear at the Butler Institute of American Art, July 9-August 20. It will be its third event since last fall, after exhibitions at Marin Museum of Contemporary Art and at Manifest Creative Research Gallery. There were almost 900 entries from 313 artists, with 83 pictures accepted.

April 9th, 2017 by dave dorsey

Head of Bodhisattva, Pakistan, Gandhara, 3rd-5th century, gray schist.

As art collectors, John and Mable Ringling fished with a net. And you get the impression that they wanted you to see nearly everything they snared in their trawls through Europe and Manhattan, even though what’s on exhibit at The Ringling in Sarasota is only a fraction of the permanent collection. You’re confronted with a numbing quantity of art in quick succession, but with a recurring revelation of brilliance in every gallery. Those little epiphanies of mastery kept luring me into a sort of Easter egg hunt as I moved from room to room.

I spent a few hours inside the museum on my last full day in Florida last week and came away extremely impressed which much of what I saw and grateful for having the chance to see the Asian wing—a rich little vein of ancient Asian art and antiquities. The exhibit of Cypriot treasures is a profound experience of the past conveying a deep spiritual resonance for any contemporary visitor interested in Asian spiritual traditions. The museum did a beautiful job in giving you an enormous roadmap, as it were, almost as long as the entire Asian wing, showing how Cyprus was positioned so that the Silk Road’s routes converged near the island. Most of the Eastern routes funneled through or around the island and then moved into Europe, therefore Cyprus naturally snagged a lot of the cargo moving from East to West. This show has been as expertly mounted as anything you would see at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—from which Ringling purchased the bulk of the collection in 1928. (One wonders how much of a bargain he might have gotten by waiting a couple years.) The Cypriot exhibit proves that this particular purchase was one of the most amazing and successful casts of Ringling’s net into the sea of world art. He may not have had the cautious and flawless taste of, say, a Duncan Phillips, but as a collector the efficiency of his methods sometimes worked beautifully.

Under the governance of Florida State University since 2000, The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art has become a significant cultural resource—and walking through it now you get the sense that you’re seeing a chrysalis that’s just beginning to open up. You get glimpses of the butterfly’s anatomy, and it’s going to be a while before you see it fly, but the metamorphosis is underway. The challenge facing those who run it now will be how much they need or want to honor John and Mable Ringling’s original intent. In many galleries, the founders created interior spaces that resembled the sort of European rooms where the work originally might have been hung—coffered ceilings in one gallery, red walls, wood paneling and trim, in many—offering an historic replica of aristocratic European interiors. For me these spaces distract from the mastery and brilliance of many individual works. The crimson walls loom around the edges of the paintings. I kept wanting to see particular paintings given a little more room to breathe and to forget the walls the way I would in the neutral white cube of a contemporary gallery. I wondered how much more powerful the enormous, lavish, maximalist cartoons Rubens painted as models for tapestries would have looked in the luminous and neutral ambiance of, say, David Zwirner’s Chelsea gallery. And there were Old Masters—Cranach, Velazquez, and Hals—that towered over neighboring work and would have been better served by being a little more removed from their lesser company. The museum is planning, over the next few years, to completely redesign the way its collection will be viewed—which was part of the pleasant anticipation I felt as I got more and more acquainted with what’s happening there. The curatorial challenge has to be both interesting and frustrating: whether or not to remain as true as possible to what the Ringlings wanted and (if those constraints matter) how to do justice to the full potential of the collection’s best work.

The overall impression you get from the core collection is that Ringling liked to buy his art in bulk to create a major cultural resource tout suite—and his focus on volume suppressed what might have grown into a more selective passion for Old Masters and Baroque art. He seemed to have been following the traditional path of the American capitalist mogul: build wealth by any available means and then elevate (and maybe redeem) yourself in the third act of your life by becoming a philanthropist. J.P. Morgan and Henry Clay Frick perfected this sort of shape shifting by creating what have become two of Manhattan’s cultural crown jewels. Likewise, the Ringling could end up being the pinnacle of Florida’s art museums. It’s one of the greatest virtues of capitalism’s concentration of great wealth into individual ownership: it can leverage world-changing projects, in very short order. Bill and Melinda Gates come to mind, among many others, and Ringling was cut from this same mold.

What’s on view right now is remarkable—for me, the survey of Cypriot Asian objects was the best reason to visit the place. The small Searing Wing, though it’s a slight overview of modern and contemporary work, offered me my first look at a painting by Jon Scheuer, a stunning piece—I’ve loved his work in reproductions but it was impossible to see the sensuous complexity of his brushwork from photographs. Seeing the actual work had a big impact on my understanding of his work. As I wrote to Bill Santelli afterward, Schueler is closer to a Romantic than an abstract expressionist, more Turner than De Kooning. It was odd that photography was prohibited in this wing when I couldn’t find a catalog for what was being shown there—and catalog sales seems to me the only rational argument against photography now, given that the current pandemic of Compulsive Instagram Syndrome seems the best way to bring people into an exhibition.

The most impressive exhibit, by far, though, in terms of the intelligence and scholarship that went into gathering and presenting the show was A Feast for the Senses—a sort of Babette’s Feast of artwork from the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance assembled to show the marriage of sensory and spiritual experience in courtly and religious ritual. It convenes more than a hundred objects from multiple sources: the Morgan Library, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Designed to offer a “multi-sensory experience,” through multiple galleries, the show infuses rooms with scents and background music or bird songs, and a few things visitors can touch. It was put together in conjunction with Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum, and deserved a much longer span of attention than I gave it. You come away from the exhibit with a view of the Late Middle Ages as a period of time much more illuminated by intelligence and wit than one might have thought, and where earthly appetites and the senses were incorporated into religious devotion. It was a fertile period, and in every piece you feel an entire civilization awakening from a long retreat from Hellenic civilization—the doorstep of an explosion in knowledge and creativity that set in motion the events that led to the world we’re living in now.

According to one of the docents monitoring a gallery in the Asian wing, The Ringling recently drew 5,000 visitors in a single day (the adjoining Circus museum has to be a huge attraction as well)—so what’s happening there is certainly working. On my way back to my car in the packed parking lot, I realized how knuckleheaded I’ve been to miss what’s been going on there over the past 15 years. The last time I’d visited in the museum was in the 90s before the current long-term restoration of the institution. I’ll be visiting every time I’m in Sarasota now.

April 5th, 2017 by dave dorsey

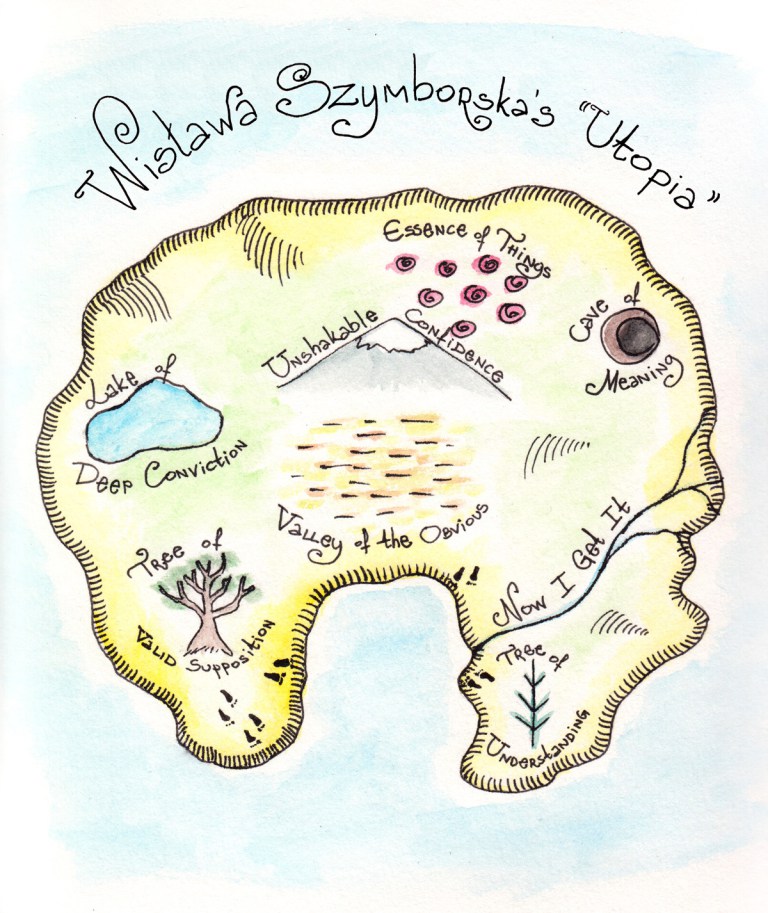

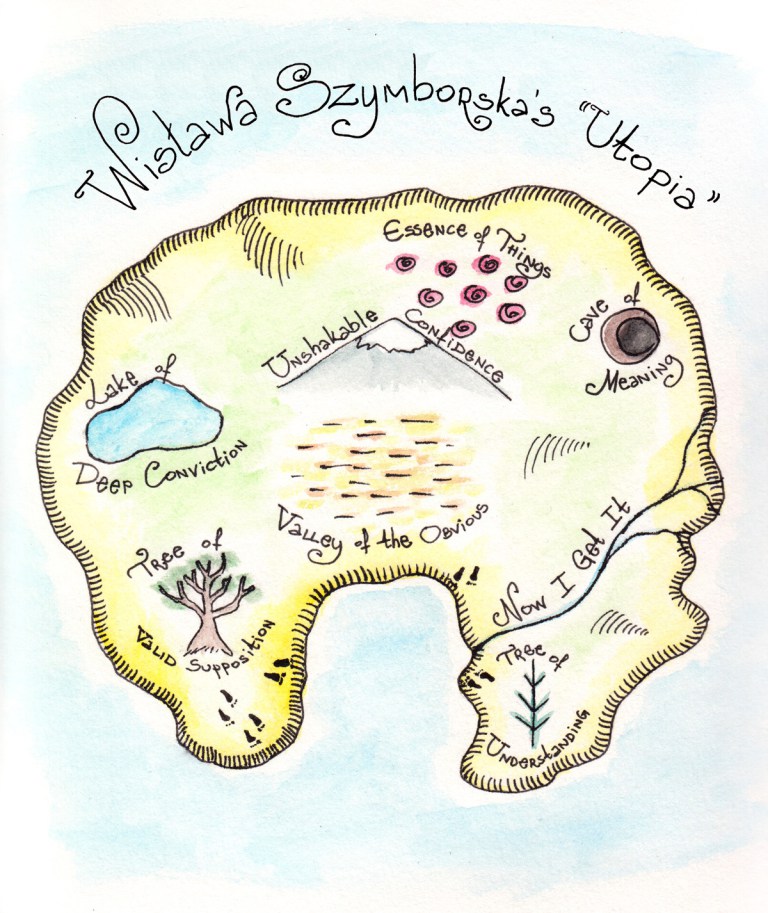

Utopia, Maria Popova

The truth, from Maria Popova in Brain Pickings:

“Attempt what is not certain. Certainty may or may not come later. It may then be a valuable delusion,” the great painter Richard Diebenkorn counseled in his ten rules for beginning creative projects. “One doesn’t arrive — in words or in art — by necessarily knowing where one is going,” the artist Ann Hamilton wrote a generation later in her magnificent meditation on the generative power of not-knowing. “In every work of art something appears that does not previously exist, and so, by default, you work from what you know to what you don’t know.”

What is true of art is even truer of life, for a human life is the greatest work of art there is. (In my own life, looking back on my ten most important learnings from the first ten years of Brain Pickings, I placed the practice of the small, mighty phrase “I don’t know” at the very top.) But to live with the untrammeled openendedness of such fertile not-knowing is no easy task in a world where certitudes are hoarded as the bargaining chips for status and achievement — a world bedeviled, as Rebecca Solnit memorably put it, by “a desire to make certain what is uncertain, to know what is unknowable, to turn the flight across the sky into the roast upon the plate.” —Brain Pickings

April 3rd, 2017 by dave dorsey

While spending a few weeks in Florida this month—helping my parents with some condo-related chores they can’t do themselves now—and getting in some morning runs on the beach, I’ve set up a little provisional studio to keep working on a current painting. (Running at low tide on the hard wet sand is the perfect surface; it gives underfoot just slightly, like an old wrestling mat.) I’d shipped the painting down, along with all the supplies I needed ahead of time, but my labors here kept me away from it for a couple weeks. It’s a little harder to spend a few spare hours on a canvas after half a day of cleaning out a garage when you have the equivalent of a mild, sunny summer day beckoning to you from the open garage door. With mockingbirds singing, ospreys building nests, jatropha in bloom, and a continuous cool breeze moving through the place from the Gulf of Mexico, it’s not as easy as it is in Western New York to keep your eyes aimed at a canvas. I even spent one afternoon at Myakka River State park checking out alligators sunning themselves on the river bank. So many ways not to work, so little time. I even spent two days driving the seven hours to Key West and back, with a full day and night in the southernmost key, stopping in Key Largo on the return to snorkel in the Atlantic coral reef.

What I found during all this time away from a canvas is that it can begin to look less and less inviting, the further in time you get from your last brushstroke. Every glance makes you wonder how much time it will take to actually complete the area you’ve started, and doubts creep in about either your ability or your enthusiasm. The charm begins to wear thin. The mojo wanes. Yet—and this is what I’ve encountered over and over, and it still comes as a slight surprise—as soon as you pick up a brush and put paint to canvas, everything snaps back into focus, the painting stirs fully awake as you break the spell. It’s as if no time has passed and the momentum returns immediately—four hours go by and you have to force yourself to put down the brush to eat.

There’s some sort of axiom in nature and in human enterprise: something is either growing or its dying. It can’t be put on hold. The longer I stay away from the work, the more it shrinks into the emotional distance and exerts less and less pressure on my attention and drive. In a sense, I can put it on pause, and it will stay as it is for as long as I stay away from it. Yet I have less and less of an impulse to return–so in a sense, it’s dying to me. What Poe called the imp of the perverse eventually takes hold: the paradoxical urge not to even look at the half-finished work when the way is open and time available to return to it. I’m drawn into a fallow period, the inertia of not painting. Yet one touch and it all comes back—because at that point, again, it’s growing into what it will become and that forward progress pulls me right back into a satisfying engagement with the work. My heart is right back in it. And the painting is as alive as it ever was. Between that stagnation and revival falls the shadow, as T.S. Eliot would have put it. I wonder how many paintings I’ve lost sight of in that shadow, without realizing all I needed to do was one step back into the light by picking up a brush.

April 1st, 2017 by dave dorsey

“In those days my world was no bigger than a couple of blocks. Huge worlds are in those two blocks. All I wanted to do was paint. It was like I couldn’t control it . . . I had tremendous freedom, my own little place that really would be such a world.” —David Lynch: The Art Life