Air, water, food and art–maybe in that order

From the sixth episode of The Anthropocene Reviewed, a witty, smart podcast about almost anything from the vantage of this era in which human beings are changing the nature of the world, intentionally and unintentionally, in ways no living creature has ever done before. This is almost the entire essay on the Lascaux caves, but the second half, on Taco Bell, is just as fine and worth the visit for a listen:

From the sixth episode of The Anthropocene Reviewed, a witty, smart podcast about almost anything from the vantage of this era in which human beings are changing the nature of the world, intentionally and unintentionally, in ways no living creature has ever done before. This is almost the entire essay on the Lascaux caves, but the second half, on Taco Bell, is just as fine and worth the visit for a listen:

So if you’ve ever been or had a child you will likely already be familiar with hand stencils. They were the first figurative art made by both our kids somewhere between the ages of two and three. My children spread the fingers of one hand out across a piece of paper and then with the help of a parent traced their five fingers. I remember my son’s face as he lifted his hand and looked absolutely shocked to see the shape of his hand still on the paper, a semi-permanent record of himself. I am extremely happy that my children are no longer three and yet to look at their little hands from those earlier artworks is to be inundated with a strange soul-splitting joy. Those pictures remind me that they are not just growing up but also growing away from me, running toward their own lives. But of course that’s meaning I am applying to their hand stencils and that complicated relationship between art and its viewers is never more fraught than when we are looking deeply into the past.

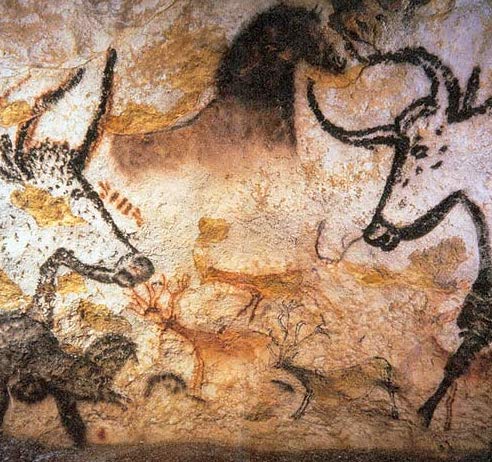

In September of 1940, an 18-year-old mechanic named Marcel Ravidat was walking his dog Robot in the countryside of Southwestern France when the dog disappeared down a hole. Robot eventually returned, but the next day Ravidat went to the spot with three friends to explore the hole and after quite a bit of digging they discovered the cave with walls covered with paintings, including over 900 paintings of animals: horses, stags, bison and also species that are now extinct, including a woolly rhinoceros. The paintings were astonishingly detailed and vivid with red, yellow and black paint made from pulverized mineral pigments that were usually blown through a narrow tube, possibly a hollowed bone, onto the walls of the cave. It would eventually be established that these artworks where at least 17,000 years old. Two of the boys who visited the cave that day were so profoundly moved by the art they saw that they camped outside the cave to protect it for over a year. After World War II, the French government took over protection of the site, and the cave was opened to the public in 1948. When Picasso saw the cave paintings on a visit that year, he reportedly said, “We have invented nothing.”

There are many mysteries at Lascaux. Why, for instance, are there no paintings of reindeer, which we know where the primary source of food for the Paleolithic humans. Why were they so much more focused on painting animals than painting human forms? Why are certain areas of the caves filled with images including pictures on the ceiling that required the building of scaffolding to create? Were the painting spiritual? “Here are sacred animals.” Or, “Here is a practical guide to some of the animals that might kill you.” Aside from the animals, there are nearly a thousand abstract signs and shapes we cannot interpret and also several negative hand stencils, as they are known by art historians. These are the paintings that most interest me. They were created by pressing one hand with fingers splayed against the wall of the cave and then blowing pigment, leaving the area around the hand painted. Similar hand stencils have been found in caves around the world from Indonesia to Spain to Australia to the Americas to Africa. We have found these memories of hands from fifteen or thirty or even forty thousand years ago.

These hand stencils remind us of how different life was in the distant past. Amputations, likely from frostbite, are common in Europe, and so you often see negative hand stencils with three or four fingers. But they also remind us that the past (artists) were as human as we are, their hands indistinguishable from ours. Every healthy person would have had to contribute to the acquisition of food and water, and yet somehow they still made time to create art almost as if art isn’t optional for humans It’s fascinating and a little strange but so many Paleolithic humans who couldn’t possibly have had any contact with each other created the same paintings the same way–art that we are still making. But then again what the Lascaux art means to me is likely very different from what it meant to the people who made it.

I have to confess that even though I am a jaded and cynical semi-professional reviewer of human activity, I actually find it overwhelmingly hopeful that four teenagers and a dog named Robot would discover 17,000-year-old hand prints. That the cave was so overwhelmingly beautiful that two of those teenagers devoted themselves to its protection, and that when we humans became a danger to that cave’s beauty, we agreed to stop going. Lascaux is there. You cannot visit. You can go to the fake cave we built and see nearly identical hand stencils but you will know this is not the thing itself but a shadow of it. This is a handprint but not a hand. This is a memory that you cannot return to. All of which makes the cave very much like the past it represents.