October 27th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Emerald Light, Elise Ansel, 2017

Cause to celebrate. Another Elise Ansel show, Time Present, at Danese/Corey already, a bit over a year since her last solo show there. November 2 – December 20, 2018 Opening Reception: Thursday, November 1, 6-8pm.

October 16th, 2018 by dave dorsey

My two jar paintings at Wausau MOCA last week.

I was honored to have Frank Bernarducci select my work for the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art’s annual juried exhibition this year. Out of respect and gratitude, I decided to attend the opening last week in a show of support for the fledgling museum. It was founded only a year ago. Its first annual, national show last year was chosen by Alyssa Monks. I hadn’t been aware of this opportunity until Bill Santelli emailed me a notice that Wausau MOCA was accepting entries for the fall. I’d been visiting Bernarducci’s midtown gallery for years on visits to Manhattan, and I welcomed the opportunity, if I got into the show, to exchange a few words with him in this less pressurized setting.

“The City Has Stories to Tell”, John Hylan

Not surprisingly, most of the work was masterful, executed in highly sophisticated ways. When you see the actual work at a show like this, it’s chastening to see, up close, how many individual paths there are toward mastery of a particular medium–it’s always humbling to see how good other painters are. As traditional as some of their methods were, the show felt ahistorical—the work didn’t look as if it had been transported into the present from any point in the past but it also, to its credit, didn’t appear to be striving for any sort of illusory cutting edge. Because Bernarducci has been selling contemporary realist painting for years in Manhattan, I anticipated it would be weighted toward representational and highly realistic work, which it was, but I was surprised at how much the work emphasized the human figure and in ways accessible to most people with or without a grounding in art or art history. You didn’t need critical commentary to love this work, but occasionally it helped, and slow, repeated observation deepened my appreciation for many of the pieces. The winning oil painting, Cindy Rizza’s Lineage, depicts the artist herself nursing her baby, sitting on a worn quilt—about as far from cosmopolitan hipster ironies as one could get. It’s a beautifully rendered vision of the most fundamental and central relationship in human life, and it served as the touchstone for the entire show. The exhibition offered an astonishing array of technical prowess in the service of a quietly jubilant, affirmative vision of human thriving. The mood was one of warmth and love and intense vitality—with some notable exceptions, including one painting of a protester tossing a Molotov cocktail and a solemn image from Geoffrey Laurence of a seated woman quietly waiting to be transported to Auschwitz.

“Departure,” Geoffrey Laurence

These reminders of social injustice were almost anomalies here. If there’s such a thing as spiritual abundance, this show was an homage to it. Photorealism was well-represented, and hyperrealism, but even in these genres, the feel of the work was affectionate and idiosyncratic—not cool and sleek and impersonal. The show demonstrated that traditional techniques and straightforward representation are firmly established, once again, as a fully contemporary way to make art. Everything in the show felt as vital and new and fresh as anything I could see tomorrow on a drive into Chelsea, maybe because a sophistication about principles of design was so prominent.

David Hummer, the director, is laboring mightily—as so many are having to do now—to find a way, economically, to give the people of his region access to contemporary art from around the country. He spoke about his remarkable and impressive plans for next year, mentioning the involvement of Vincent Desiderio and Bo Bartlett, among others.

“Listening to Silence,” Ali Cavannaugh

The power and honesty of the show Bernarducci selected made me feel slightly abashed about my insistence that art works subconsciously and directly, in ways that don’t depend on subject matter. There was much implied narrative on view in Wausau, and it was powerful. Much of that power derived from the way it was painted, yet content mattered at least as much. One could use a show like this as evidence for an argument that art’s other greatest virtue, beyond the subconscious disclosure of a world, is to make visible what makes us human in the most obvious way possible, by depicting human beings. This show demonstrates you can put aside most of modernism and much of what has come afterward and still get this job done perfectly, without losing anything important in the process, including relevance to the contemporary world.

I did get a few minutes to talk casually with Bernarducci. I’m surprised to say that his manner, his kindness and geniality and unassuming role at the event were endearing. Somehow I’ve never thought to use that adjective to describe an art dealer until now, but it was exactly the impression he made. I suppose I could have arranged to speak with him in the past on a visit to his previous Midtown location, but somehow in that setting I would have felt as if I were getting between him and the ongoing fight to stay afloat that galleries face now in Manhattan. (Something they have in common with museums in Wausau, Wisconsin.) I got to know him a bit between his absorbed bouts of texting–the pressure of his life in New York followed him to the Midwest thanks to his smart phone. He said he’d gotten married in Wisconsin and he enjoyed coming back, though he was a clearly a New Yorker. He talked a bit about the economic battle for gallery owners in Manhattan and his recent new venture downtown, and he said he’d be happy to sit down and speak with me at more length on a visit to the city, with enough notice. (Afterward, I thought I should have assured him I could use a siren to give him time to find shelter, if that helped. Some people might take me up on that.) He won me over with his refusal of the spotlight when it came time to announce the prize winners, along with the look of near-anguish on his face when he said that deciding on the winners was one of the worst experiences of his life. He was not being hyperbolic. It was obvious that he hated having to eliminate all of us who didn’t make the cut for an award. Just mentioning it the way he did seemed to drain him. He struck me as a good man, fighting the good fight from his corner now in Chelsea, with nothing guaranteed, even after his decades in the business.

“Ivet,” Shane Scribner

He came to the right place: Wisconsin itself struck me the same way. It’s a long way from Silicon Valley and Brooklyn, but it’s holding its own. Wausau was a picturesque town that looked surprisingly new—as if a lot of what I saw had been developed within the past ten or twenty years. Wages aren’t quite as high as the national average there, but it had the aura of a small city with a fairly vibrant local economy, in a hilly setting that was even more beautiful with its foliage near peak autumn color.

But what struck me most deeply about the state was a moment on the highway as I drove north to attend the opening. I flew into Chicago and drove to Wausau in a rented Nissan, listening happily to podcasts in a steam of comfortably spaced cars doing around 80 for most of the trip on Interstate 90. About halfway to Wausau, my Google Maps route turned red and traffic slowed dramatically. Here’s what was so marvelous: very quickly, the cars in the right lane began to merge into the left one, as I followed the example of the fellow ahead of me. A couple cars passed and merged ahead of us, but that was all. Soon all the drivers were slowly crawling forward in the left lane—far ahead of the need for any of us to be in one lane. The bottleneck was still well ahead of us and the right lane now was entirely open and free of cars. No one, not a single driver, was speeding down the right lane in order to get up to the most advanced possible spot for the two lanes to merge. In other words, nobody was doing what drivers in every other state seemed to have learned to do—stay in that right lane until the very last moment when you have to merge left in order to shave a minute or two off one’s drive time and cut into line far ahead of all the others who have already politely taken their place in the slow lane. The right lane seems to have become the passing lane, at least where I live, and people roll up to the red light just waiting to engage in a drag race to get ahead of as many people in the left lane after the light turns green—and the same principles seem to apply in most places on the highway when construction is in progress. But not in Wisconsin. They’re actually courteous when they get behind the wheel–more than willing to respect the place of others who have already queued up. A quarter mile of slowly moving forward with absolutely no one cutting out into that empty right lane in order to get ahead—it was almost poignant. This was civility. I’m glad I made this trip, despite the cost and the time involved. It was worth it.

October 11th, 2018 by dave dorsey

Still Life, Gillian Pedersen-Krag

There’s a funny and moving scene in Amadeus where Mozart defends his music for The Marriage of Figaro. His monarch cites good reasons for prohibiting a performance of the story: it’s immoral, degenerate and revolutionary in spirit. (The movie suggests that some might have thought of Mozart’s own personal life in those terms, on occasion.) The king fears that a performance of the opera might inspire insurrection. France is on the verge of political chaos. Austria worries about the contagion. Yet Mozart dismisses all of these considerations, and his fervor about what he’s done in his composition is entirely about the formal brilliance of his work: the libretto may be subversive, disruptive and potentially violent, but his music is the embodiment of harmony and order. He’s living on an entirely different plane from those around him, playing a glass bead game with notes, striving for transcendent harmonies, merging many voices into one melody, with a passion for conveying nothing more than the quick joy of life itself.

The king: “Figaro is a bad play. It stirs up hatred between the classes.”

Mozart: “Sire, there is nothing like that in the piece. I hate politics. The end of the second act for example. It starts out as a simple duet. Just a husband and wife, quarreling. Suddenly, the wife’s scheming little maid comes in, duet turns into trio. Then the husband’s valet comes in. Trio turns into quartet. Then the stupid old gardener comes in. Quartet turns into quintet. On and on. Sextet, septet, octet. How long do you think I can sustain that, your majesty? Twenty minutes. If that many people talk at the same time, it’s noise. Only opera can do this. But with opera, with music, you can have twenty individuals talking at the same time and it’s not noise, it’s a perfect harmony.

For him, it isn’t what anyone in the opera is saying that matters. What matters is MORE

October 10th, 2018 by dave dorsey

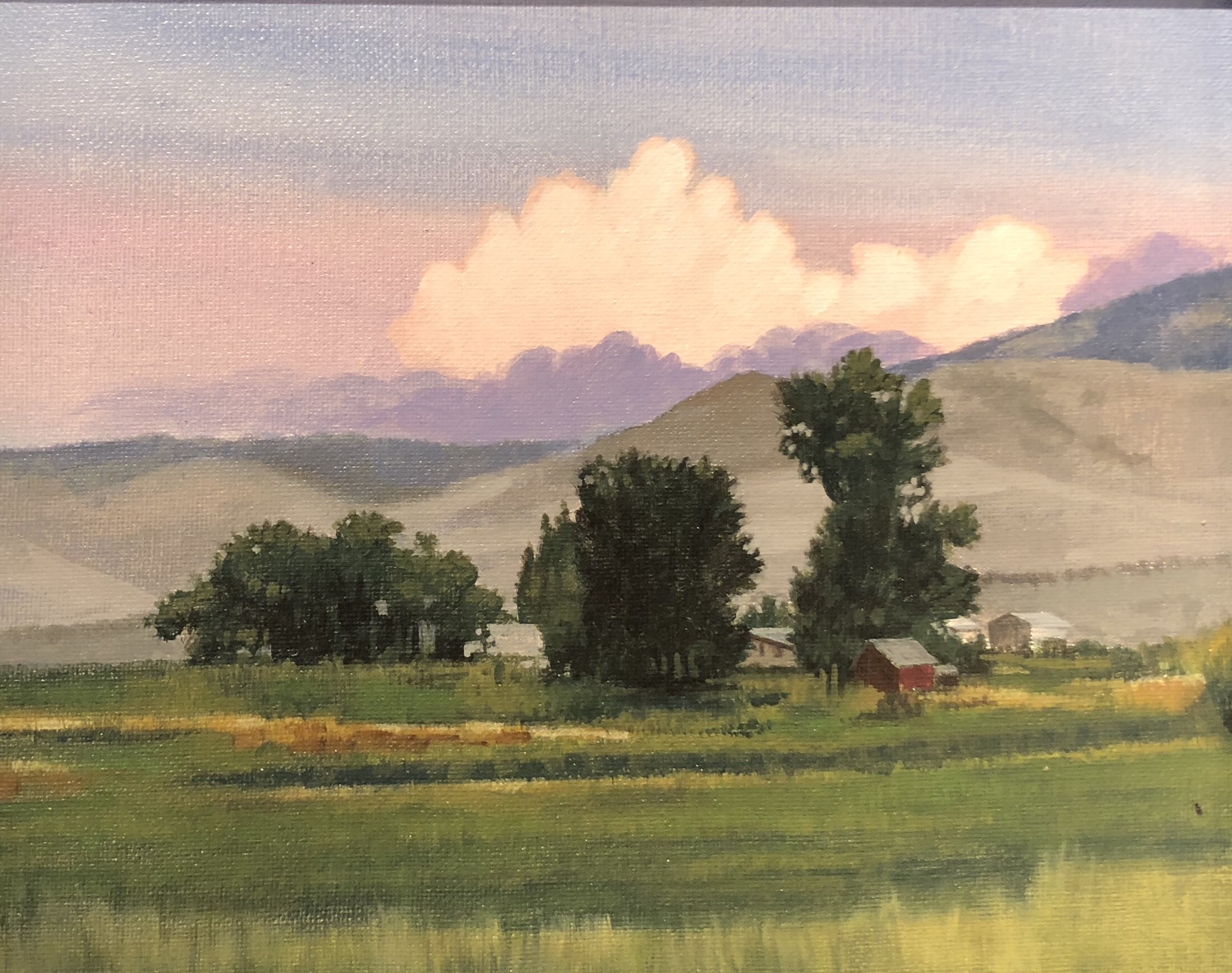

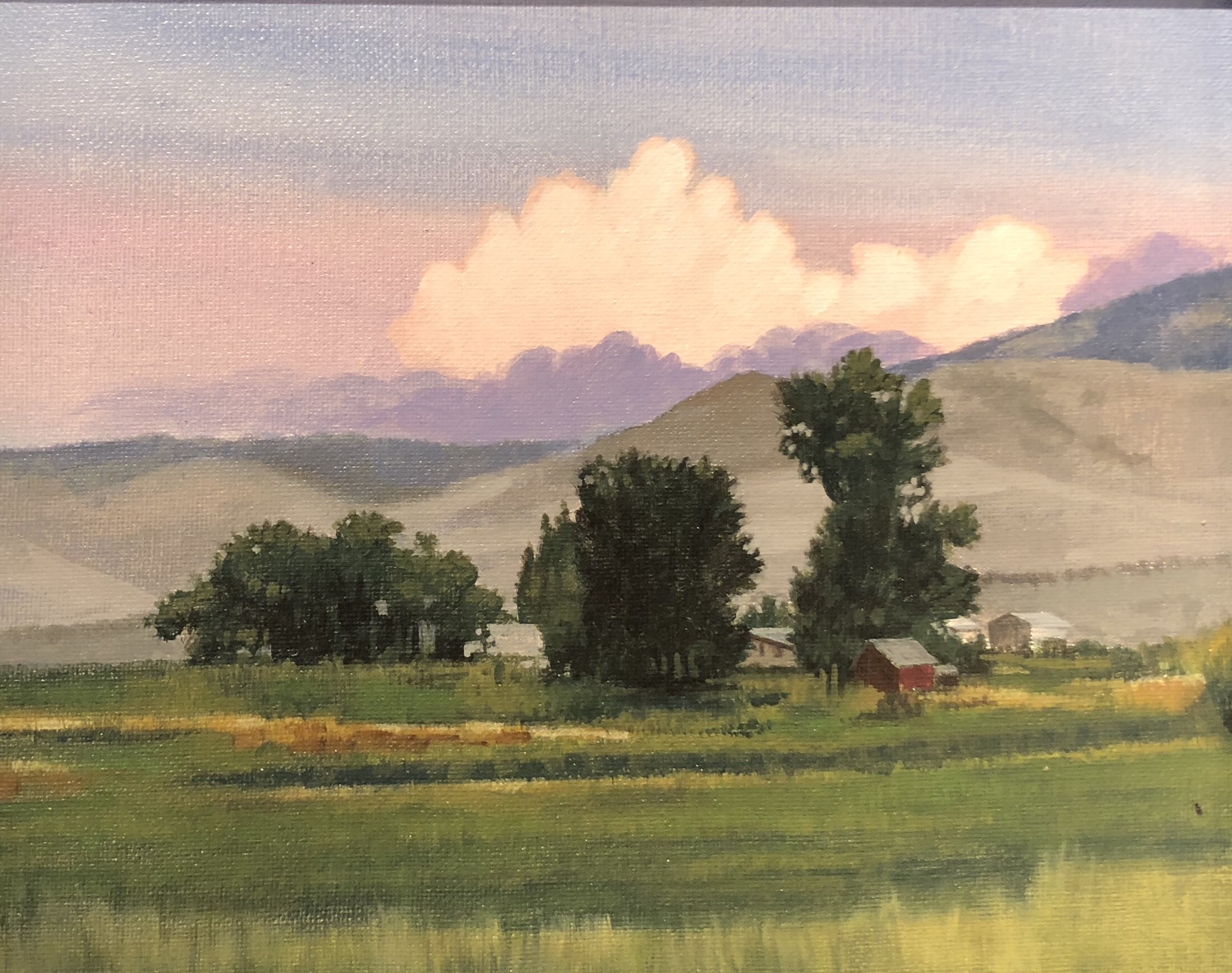

These are small, beautifully executed landscapes by Bill Finewood, currently on view in “Methods Change but the Spirit is the Same”, at the Insalaco-Williams Gallery 34, Finger Lakes Community College. It’s a great overview of his work in different mediums and styles throughout his career. These oils were stand outs in composition, color and handling of the medium, resonant with the unique light of a particular time of day and season. The show also includes a marvelously tactile and detailed drawing of a rabbit, a bit of an homage to Durer’s famous and incomparable one.