February 11th, 2020 by dave dorsey

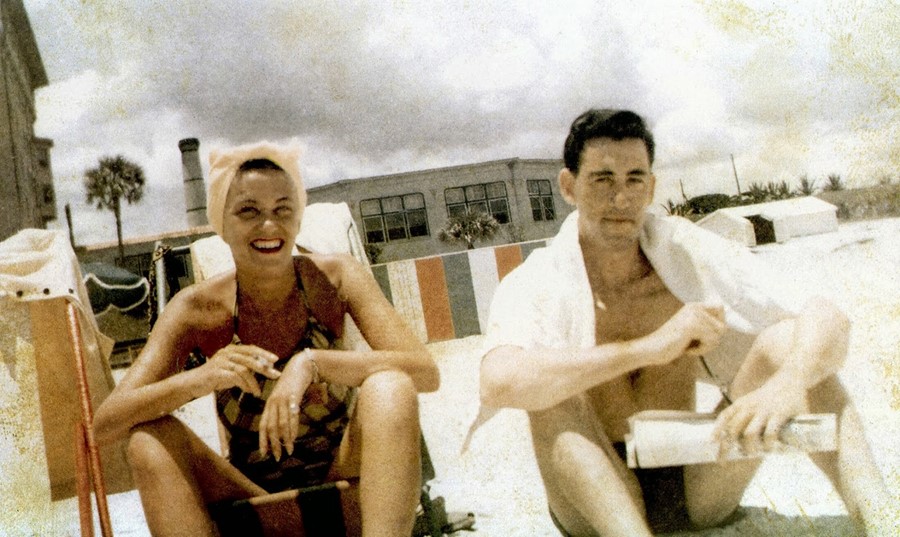

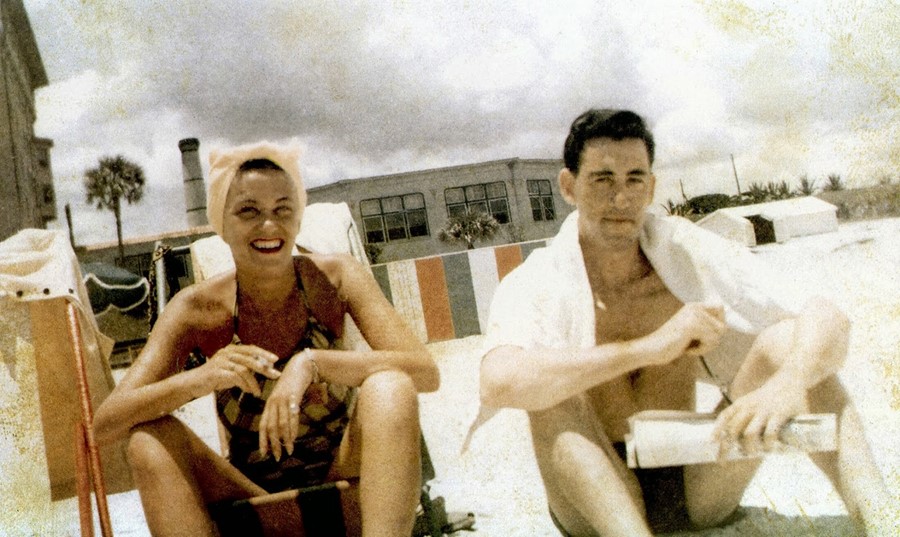

Sans bananafish, J.D. Salinger with his sister, Doris

Some flava in ya ear (if you read this aloud.) I mean, seriously, a lot of flava. J.D. Salinger’s recipe for popcorn (I hope the measure for the popcorn itself represents the amount of unpopped kernels). This was a small contribution to the exhibit of personal items from his archives at the New York Public Library. The salutary effect of the exhibit was to bring into relief how happy, if not blissful, Salinger’s life was in Cornish. He liked him some Hitchcock. He loved spending time with his grandkids. He read books about spies and kept the Associated Press Stylebook on a shelf in his bedroom. He could write letters like nobody’s business. And, OK, he was a little weird, but the weirdness was at the heart of how great he was, and, besides, aren’t we all, a little? It was cool to learn that had a Chevy Blazer, from way back close to when GM started to market them, to haul the firewood he cut.

For 1/2 cup of popcorn:

6 tsps sea salt

2 tsps paprika

1 tsp. dry mustard

1/2 tsp garlic powder

1/2 tsp celery powder

1/2 tsp thyme

1/2 tsp marjoram

1/2 tsp curry

1/2 tsp dill powder

February 8th, 2020 by dave dorsey

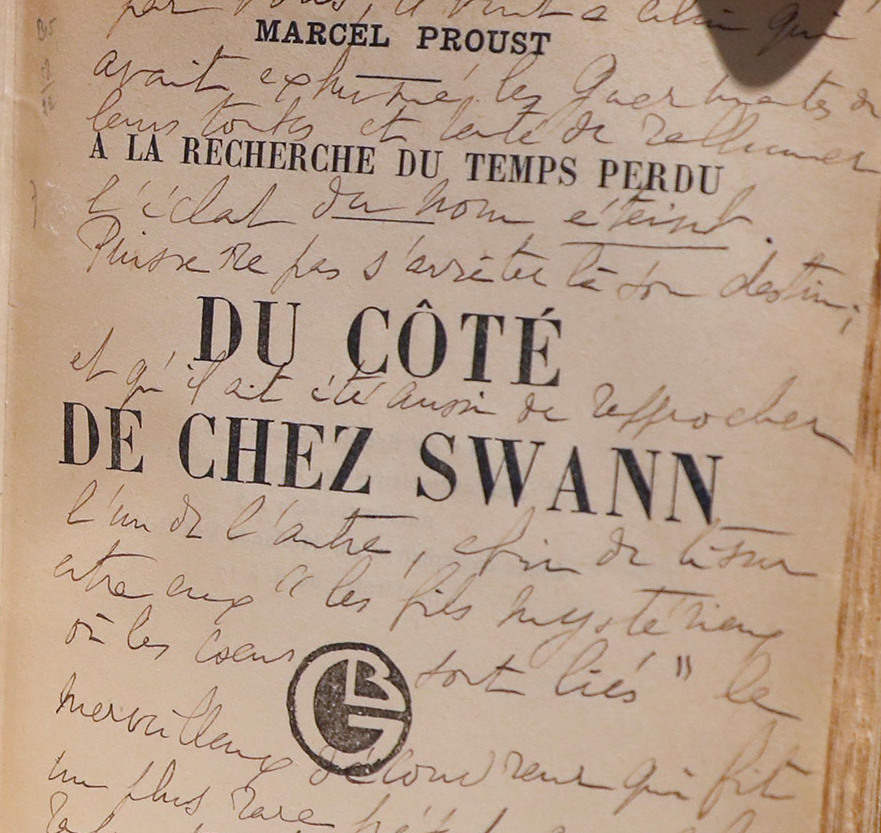

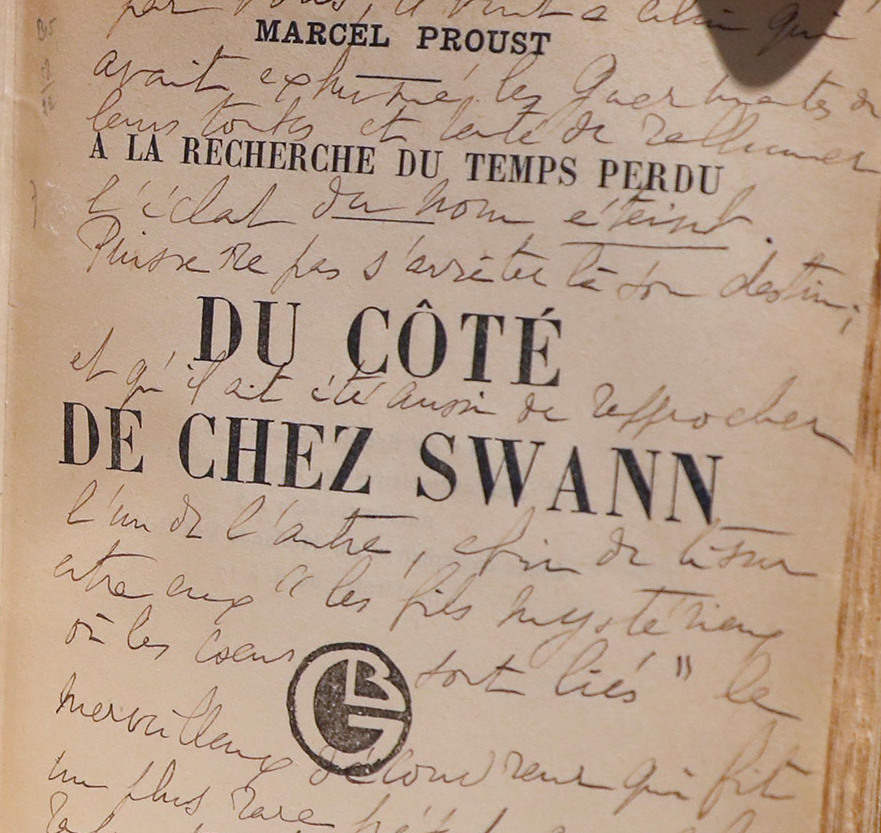

An orginal edition of Swann’s Way from Proust archives. Photo by Getty

Why art runs in parallel to science as a way of discovering what science can’t plumb, sort of the corrolary of chemical elements in the structure of human subjectivity, the human heart, from Swann’s Way:

When, after that first evening at the Verdurins’, he had had the little phrase played over to him again, and had sought to disentangle from his confused impressions how it was that, like a perfume or a caress, it swept over and enveloped him, he had observed that it was to the closeness of the intervals between the five notes which composed it and to the constant repetition of two of them that was due that impression of a frigid, a contracted sweetness; but in reality he knew that he was basing this conclusion not upon the phrase itself, but merely upon certain equivalents, substituted (for his mind’s convenience) for the mysterious entity of which he had become aware, before ever he knew the Verdurins, at that earlier party, when for the first time he had heard the sonata played. He knew that his memory of the piano falsified still further the perspective in which he saw the music, that the field open to the musician is not a miserable stave of seven notes, but an immeasurable keyboard (still, almost all of it, unknown), on which, here and there only, separated by the gross darkness of its unexplored tracts, some few among the millions of keys, keys of tenderness, of passion, of courage, of serenity, which compose it, each one differing from all the rest as one universe differs from another, have been discovered by certain great artists who do us the service, when they awaken in us the emotion corresponding to the theme which they have found, of shewing us what richness, what variety lies hidden, unknown to us, in that great black impenetrable night, discouraging exploration, of our soul, which we have been content to regard as valueless and waste and void. Vinteuil had been one of those musicians. In his little phrase, albeit it presented to the mind’s eye a clouded surface, there was contained, one felt, a matter so consistent, so explicit, to which the phrase gave so new, so original a force, that those who had once heard it preserved the memory of it in the treasure-chamber of their minds. Swann would repair to it as to a conception of love and happiness, of which at once he knew as well in what respects it was peculiar as he would know of the Princesse de Clèves, or of René, should either of those titles occur to him. Even when he was not thinking of the little phrase, it existed, latent, in his mind, in the same way as certain other conceptions without material equivalent, such as our notions of light, of sound, of perspective, of bodily desire, the rich possessions wherewith our inner temple is diversified and adorned. Perhaps we shall lose them, perhaps they will be obliterated, if we return to nothing in the dust. But so long as we are alive, we can no more bring ourselves to a state in which we shall not have known them than we can with regard to any material object, than we can, for example, doubt the luminosity of a lamp that has just been lighted, in view of the changed aspect of everything in the room, from which has vanished even the memory of the darkness. In that way Vinteuil’s phrase, like some theme, say, in Tristan, which represents to us also a certain accretion of sentiment, has espoused our mortal state, had endued a vesture of humanity that was affecting enough. Its destiny was linked, for the future, with that of the human soul, of which it was one of the special, the most distinctive ornaments. Perhaps it is not-being that is the true state, and all our dream of life is without existence; but, if so, we feel that it must be that these phrases of music, these conceptions which exist in relation to our dream, are nothing either. We shall perish, but we have for our hostages these divine captives who shall follow and share our fate. And death in their company is something less bitter, less inglorious, perhaps even less certain.

February 5th, 2020 by dave dorsey

Peggie Blizard. Pink Flowers in Water, Oil on Panel, 30 x 24

I’m partial to jars. I love the way a Ball jar’s particular utility lends character to its shape and surface, and how everything flows from its usefulness, its handle, the gemlike refractions of the embossed logo, and especially the glass threads for the lid around the lip. Along with its generally humble demeanor. When I walked into the little room where Peggie Blizard’s solo show was on view at George Billis (yet another discovery for me there), my immediate reaction was that I wished I had done the paintings myself. (It’s the way I usually react to work I love.) Her translucently blue and colorless, transparent Ball jars have a squat, almost muscular repose that give weight to the dense delicacy of her seemingly random bouquets, loading the center of the canvas with a gorgeous and rigorously rendered entanglement of color and line. Each painting is an improvisation within the same format: the rampant complexity of flowers thrust into the smooth and simple and uniform tones of the glass, echoed by the slight variations in sunlight on the uniform wall behind the jar, which serve to unify the multiplicity of shapes and tones, centering them, concentrating them into a static explosion. With ingenuity, she has stuffed blossoms down into the jar, mingling with the stems, to extend and push her cluster of lustrous color down to the bottom of the panel. The tones are conveyed with passionate accuracy, and the light brings to mind Janet Fish’s sunny still lifes at their brightest. Her show ends in a few days.

February 2nd, 2020 by dave dorsey

Christopher Burke’s work hanging in back at George Billis in Chelsea. Billis is at work on the computer, at the right.

Though three other artists at George Billis Gallery in Chelsea were having solo shows in the temporary space Billis had arranged to use next door to permanent location (undergoing renovation), he still managed to have maybe eight or nine paintings by Christopher Burke hanging in the office hallway. It was the first time I’ve been able to see the actual paintings, having followed him on Instagram with great interest. There’s a subset of artists I follow on Instagram who, like Burke, are working to find ways to make images representationally persuasive but also effectively abstract in one way or another, none of them much like any of the others: Burke, Joshua Huyser, Jessica Brilli, Harriett Porter, Mark Tennant, James Neil Hollinsworth, Harry Stooshinoff, Mitchell Johnson and many others. Each of them is representational and abstract in different ways.

Burke’s work holds up no matter how close you get to it. This is not something I can say about a number of otherwise amazing painters. (Walton Ford’s paintings are breathtaking , but up close, when you get near the actual work, the marks seem expedient and for some reason, disappointing, though it’s hard to say in what way. In a discussion with my friend Rick Harrington, now living and painting in Oregon, I learned that he’d had the same reaction. The images are stunning; the paint itself not so much, though neither of us could say why it mattered in terms of the quality of what he does. And Ford would hardly care about our disappointments.) All of which is an awkward, roundabout way to say Christopher Burke’s paint holds up from any distance, something I wanted to confirm by paying a visit to Billis on my short trip to Manhattan–having been unable to get to Burke’s show here late last year. His choice of subject is crucial to what he’s doing. The images, both his carefully composed portions of roof and sky as well as his drone-like perspectives of flood plains, offer him that perfect balance between abstraction and precise realism. What’s marvelous is how much feeling Burke can invest in images so minimal and geometric. Visually, Sheeler was up to something similar in Conversation–Sky and Earth, but Burke’s images are beautiful in a more vulnerable way, partly because of their almost Japanese aura of loneliness and emptiness. These humble corners of the sky keep company with an empty, silent billboard jutting up into view, an abandoned water tower gathering shadow, the dusk soon to make everything in these paintings invisible. No one’s around. The power lines sag. Birds congregate somewhere else. Everything is rendered with absolute care and rigor and even tenderness; everything is just as it needs to be. There’s nothing lacking in the painting nor in the world Burke just barely reveals to you.