Passive transformation

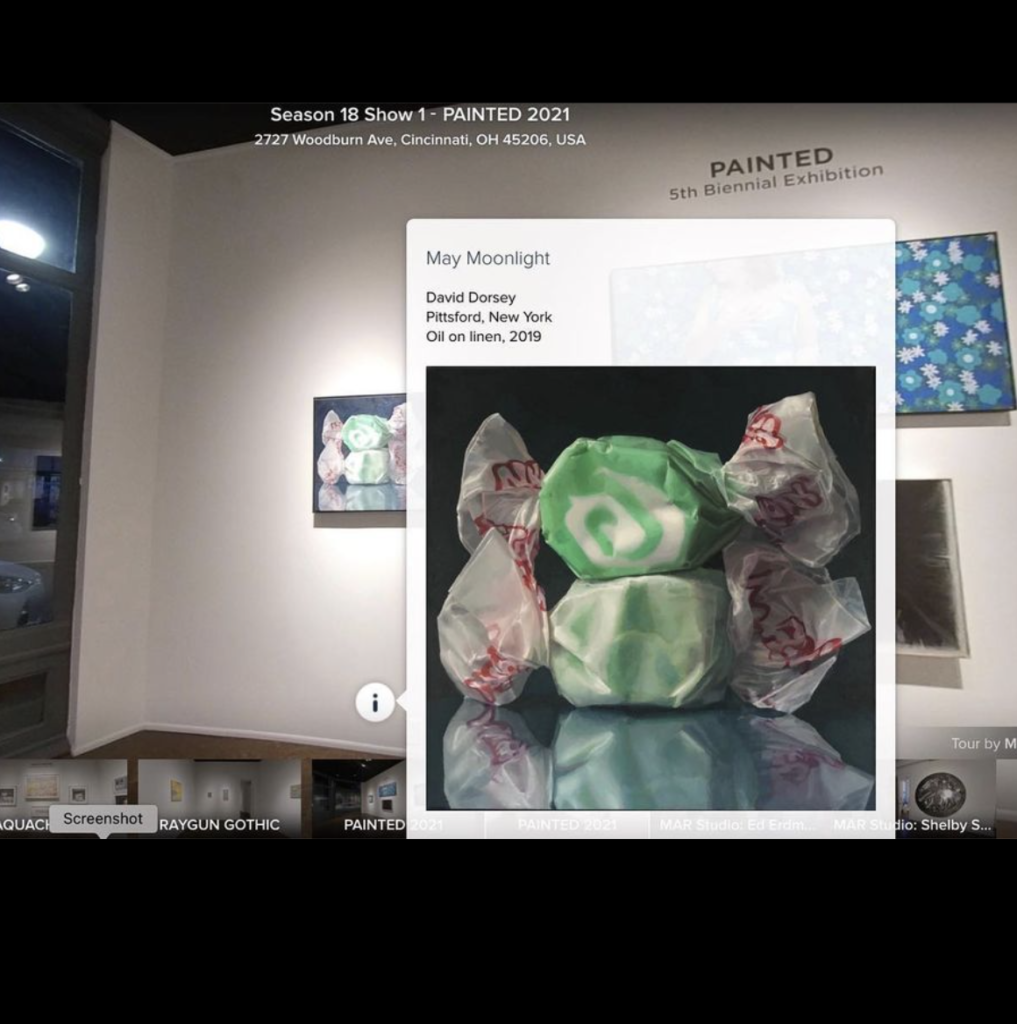

A screenshot from the online tour of Manifest’s Painted exhibition.

While the Painted exhibition was still running at Manifest Gallery, in Cincinnati, late last year, I participated in a Zoom conference with around a dozen artists whose work was chosen for Painted and the gallery’s other concurrent exhibitions. It was fun and humbling, because some of the other artists were conversationally eloquent about their work and art in general, while I felt bashful and halting by comparison. After more than a decade of writing about visual art, you would think I’d have been an open spigot of confident opinions, but that isn’t how it felt. Adam Mysock, Education and Studio Program Manager at Manifest, moderated the conversation. Of course, some of it was inevitably about what the artists were trying to achieve in their work. What they intended for their work to do for a viewer. How the work was the outcome of purposeful intent and had designs on a viewer’s perceptions, ideas, emotions, and so on. Later in the online conference, Mysock asked a question that got crickets from the participants: “So is it possible to imagine an entirely passive way of painting?” I thought at the time it was a question worthy of the sort of strenuous meditation a Zen adept brings to a koan and was especially pertinent to anyone who works with photo-realistic methods as I usually do. I couldn’t think quickly enough on my feet, partly because it’s subtle and complicated and a little paradoxical. The question has continued to haunt me and only recently have I realized I should have at least said that whole issue is central to what I’ve always sought to do in representational work.

Most people, including painters, think of style—the signature of the painter’s heart in every detail of the finished work—as the essence of the work’s originality and value. So the way in which an artist distorts, shapes, censors, simplifies, or translates what he or she sees into a unified image establishes the value of that particular painter’s work. This would appear to be an entirely active process: the outcome of complex, continuous choices as the picture is being painted. At some point, Fairfield Porter said something that probably wouldn’t be repeated by most painters now, but it’s a simple way to imagine what even photographically accurate painting actually does: to depict the world, just as it is, while making it a little more beautiful. It sounds like a recipe for the equivalent of sentimentality: trying to make the world more beautiful than nature did. But that isn’t what he meant. I think he was talking about how the process of transforming natural vision into a painted image mysteriously reveals the beauty that’s there but unrecognized in what a person looks at but doesn’t really see every day. How that transformation occurs is the essential mystery of the whole pursuit. Porter simplified what he saw, reducing a wealth of detail to one or two strokes of paint in some cases, made countless choices to eliminate aspects of what he saw and alter a color here or there, or everywhere, for that matter, to harmonize it with others on the canvas. He made active choices that had some conscious or subconscious end in mind, his goal or purpose, even if that purpose was merely to complete the work in a way that enabled every little part to be indispensable to the work’s visual unity. It would seem to be an intensely active, not passive, process.

But he was hoping that his work would do nothing more than capture “the light in the room” just as it was, the moment in time and place, even if much of what the light revealed to his observant eye gets lost in its resolution into paint. His painting of tennis players has that quality of being exactly how the court looked just as one of the players served the ball, the bright mid-day light intensifying the whites and flesh tones, deepening the darks of the shadows behind them, even though most detail was erased in the way he applied his paint. There’s no purpose here other than to convey the entire experience of that moment, and he succeeds in such a way that you can smell the air and feel the warmth of the sun on the backs of the players. In that sense, what he’s doing is utterly passive, honoring a simple, trivial moment in all its vitality and beauty and order. His paintings are an homage to this sort of mindfulness and humble appreciation of the mostly unregarded glory of ordinary life, from hour to hour—as were the paintings of Vermeer and Chardin and most of the Impressionists and the perceptual painters now. And most landscape painting in general. In other words, he worked as part of a long tradition very much still alive now.

For the record, over the past year, I’ve become interested in art that does just the opposite. MORE