Viridian’s juried show

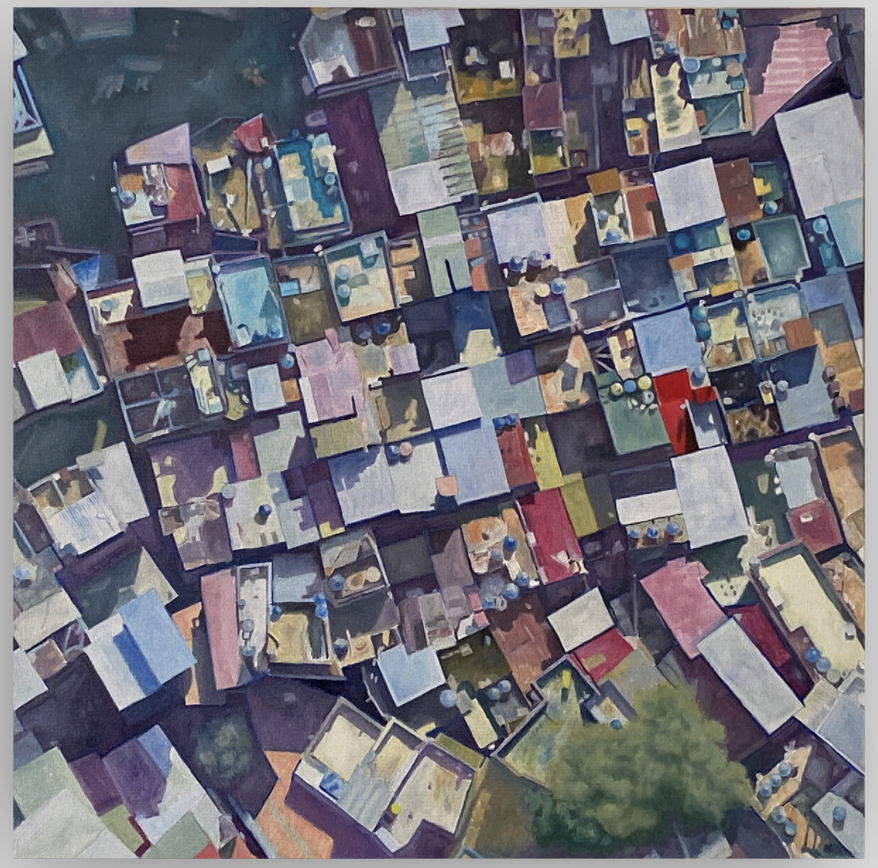

“Rocinha Series 3 No 1”, Alan Garry, 32 x 32, Oil and graphite on canvas

Before I get to my impressions of the juried show currently on view at Viridian Artists, allow me a digression about the location depicted above in one of the exhibition’s paintings.

On a visit to Fiji, my son reported back to me that he found there the poorest and happiest people he’d ever met. I was reminded of that brief report (which included first-person details about indigenous volleyball) when I looked up Rocinha, a famous, densely-populated favela that evolved organically and spontaneously near Rio de Janeiro. It’s occupied by those who can’t afford to live in the more expensive, planned urban areas of the city. It’s a borough scaled for human beings, growing and developing virtually without urban regulation or oversight, with a self-organized, makeshift structure, improvised and wildly colorful. It’s a libertarian’s nightmare that seems to be trying to grow into a libertarian’s dream. The population is packed into tight spaces, structures rarely rising beyond three floors. Nothing looms over anything else there except the upper reaches of the steep hillside on which everything higher up is the same size as everything lower down.

Close to a quarter million people now live in Rocinha, and they get around mostly by foot on a few roads and alleys and paths that snake through the place. As Rio has grown, it has enveloped this encampment that has been crystallizing into a suburban town, now that it’s centrally located. (In a way, the economic mountain came to Mohammad and surrounded him.) It is becoming more modernized so that almost all structures now have plumbing, electricity and sanitation.

From Wikipedia:

Compared to simple shanty towns or slums, Rocinha has a better developed infrastructure and hundreds of businesses such as banks, medicine stores, bus routes, cable television, including locally based channel TV ROC (TV Rocinha), and, at one time, a McDonald’s franchise.[2] These factors help classify Rocinha as a favela bairro, or favela neighborhood.

It’s the urban equivalent of an outlaw entrepreneur, someone more interested in growth than legality. The name Rocinha means “little farm.” This mid-sized city sits on a hillside that has been the backdrop for various productions like Rio and Children of Men. As in Mexico, tourists to balance its attractions against the chance of being collateral damage in a gang battle. I found a great portrait of the daily life there in a little free-form essay, picturing a culture of vibrant struggle—on the cusp between squalor and organized growth, marginalization and creative vitality, legal and illegal. It sounds like a more violent and darker version of Steinbeck’s Cannery Row:

Brazilian culture is happy: multicultural artistic expressions, music, dance, jokes and spontaneity. Meetings on street corners, children playing in the street and parties with music on the squares are all ubiquitous. That is life in Rocinha. People hardly have private space and share the small amount of public space available.

Few people drive a car. Most people walk or take buses, vans or motor taxis.

In less than a square kilometer, you can do your shopping, fix a motorcycle, find a barbershop, buy food, pick up a video, and go to the church or the gym. None of these establishments exceed eight meters of street façade, some occupy only one. Commerce and services are mixed with housing, which primarily occupies floors above the street level. Around 6 o’clock in the afternoon, the neighborhood looks like a shopping mall corridor during the days before Christmas. It’s on the street that old friends meet and the community issues are discussed. Rocinha, like the thousands of other slum areas throughout the world, reveals miserable, inhumane conditions, including poverty, crime and filth at the one hand, and urban vitality among the people and in the streets on the other.

That last part also sounds like the visible homelessness surrounded by high-priced real estate in midtown New York City during the pandemic, as well as some famous West Coast cities now.

I learned all this in order to get a more informed look at a painting included in Viridian Artists’ annual juried show, running through Jan. 28. The exhibition is unusually interesting, but in ways that aren’t sensational. There are small, seemingly minor paintings that stood out for me, work that seems above and beyond whatever else I could find by that artist online. Much of this work is humble but assured and holds the viewer’s attention. I was a member at Viridian a decade ago and had one of my few solo shows there, and I don’t recall seeing work this consistently quietly interesting, as a whole, assembled there in the past.

The entry that inspired me: “Rocinha Series 3 No 1” by Alan Garry. It’s a drone’s eye view of the slum-cum-McDonald’s/drug cartel service region. It works as a geometric abstraction that resolves into a realistic image in seconds as you gaze at it and then recognize the gauzy tree in the lower corner. At that point, everything else sharpens into view and the little dots appear to be caps on smokestacks as the squares become roofs. What seemed to be little boxes afloat on a stream, collected into an eddy near shore, now become randomly arranged homes with almost no space between one and the next. At first, there’s an impersonal anonymity to the image that reflects the poverty, the numberless lives that come and go, unrecognized, beneath the roofs. Yet the energy of the image (it reminded me a bit of Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie Woogie without all his negative space) you sense you are observing a bustling human community from on high. From the air, it seems somehow inviting and beautiful, lively by virtue of the obviously haphazard way in which it has grown upward and outward from the cramped, snaking paths that run through it.

Other work that stands out: Faux Relic: Humble Things is a diminutive fantasia of insects, ferns, trees and skunk cabbage, a scene fit for the imagination of Durer or Burchfield but looking more like an illustration for Lewis Carroll. It’s illuminated by a hazy light that emanates from a distant horizon behind the big bumblebee floating up from the foliage. The oil-on-linen painting is contained in a frame as intricate as a reliquary, seemingly hand-carved and gilded, adding significantly to the mood of the little painting, where the subject seems less about nature than the state of mind required to dream about nature. Much has been written about the loss of enchantment in the past century, but this painting does a good job of making it visible again. The frame is an integral part of the image as it is with Howard Hodgkins, though the painting here isn’t extended outward onto the painting with the exception of a cameo image of a bullfrog mounted in the lower frame, like a medallion. It’s a dreamy, eccentric, deeply personal and idiosyncratic piece of work by Kei J. Constantinov.

Other work that stands out: Faux Relic: Humble Things is a diminutive fantasia of insects, ferns, trees and skunk cabbage, a scene fit for the imagination of Durer or Burchfield but looking more like an illustration for Lewis Carroll. It’s illuminated by a hazy light that emanates from a distant horizon behind the big bumblebee floating up from the foliage. The oil-on-linen painting is contained in a frame as intricate as a reliquary, seemingly hand-carved and gilded, adding significantly to the mood of the little painting, where the subject seems less about nature than the state of mind required to dream about nature. Much has been written about the loss of enchantment in the past century, but this painting does a good job of making it visible again. The frame is an integral part of the image as it is with Howard Hodgkins, though the painting here isn’t extended outward onto the painting with the exception of a cameo image of a bullfrog mounted in the lower frame, like a medallion. It’s a dreamy, eccentric, deeply personal and idiosyncratic piece of work by Kei J. Constantinov.

Another small, extremely modest abstraction, Water Music, by Stephanie Lempres, has the charm of a miniature Milton Avery, a scene assembled with seemingly torn areas of subtle color, mostly gray, yellow and pink. The pink area rules the upper half of the image like a sunset. Brown and gray shards fit together loosely into a patchwork of dunes or hills surrounding a bright yellow path or road that disappears into the distance past a wedge of green, a little wooded valley fed by the watershed from the hills maybe. It’s understated, implying more than it shows, doing just enough to set up the color harmonies and make it all come alive with a hopeful sense of ambient afternoon or morning light, all of it achieved with the simplest, almost childlike collage of flat organic shapes, one spot of color next to another, as Hawthorne put it.

of a miniature Milton Avery, a scene assembled with seemingly torn areas of subtle color, mostly gray, yellow and pink. The pink area rules the upper half of the image like a sunset. Brown and gray shards fit together loosely into a patchwork of dunes or hills surrounding a bright yellow path or road that disappears into the distance past a wedge of green, a little wooded valley fed by the watershed from the hills maybe. It’s understated, implying more than it shows, doing just enough to set up the color harmonies and make it all come alive with a hopeful sense of ambient afternoon or morning light, all of it achieved with the simplest, almost childlike collage of flat organic shapes, one spot of color next to another, as Hawthorne put it.

Pen and Alejo, Emily Fisher’s archival inket print of her photographic portrait of a blond child more or less holding hands with his rooster brings to mind Sally Mann and Emmet Gowin’s haunting images of childhood, but in a more formally posed setting. It’s also more colorful and direct, but just as arresting, the rooster’s red crop set against the complementary green background. The juxtaposition of the child’s naked and vulnerable chest against the bird’s full plumage and pointed beak creates a play of opposites that work off the dominant red/green color.

Pen and Alejo, Emily Fisher’s archival inket print of her photographic portrait of a blond child more or less holding hands with his rooster brings to mind Sally Mann and Emmet Gowin’s haunting images of childhood, but in a more formally posed setting. It’s also more colorful and direct, but just as arresting, the rooster’s red crop set against the complementary green background. The juxtaposition of the child’s naked and vulnerable chest against the bird’s full plumage and pointed beak creates a play of opposites that work off the dominant red/green color.

There’s much other work in the show to justify a visit to the gallery, located with a number of other artist-funded galleries that often present intriguing juried exhbitions every year in the same location, at the north end of Chelsea, where Hudson Yards begins.

Comments are currently closed.