Manet’s brilliant little movies

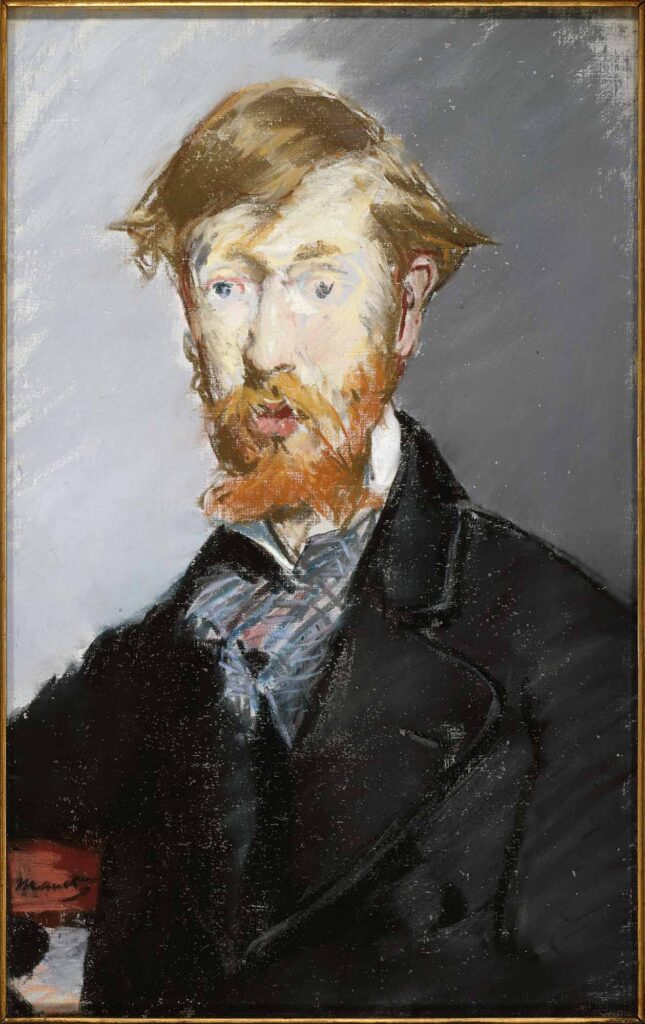

George Moore, pastel on canvas, 21 3/4 x 13 7/8 in.

Upcoming: Manet/Degas, September 24th, 2023 – January 7th, 2024, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

1

It’s probably reasonable to say Manet had a weakness for beautiful women, since he died of complications of syphilis. His weakness was also his strength. Women, especially attractive ones but not always, were the most compelling motif of his paintings and his perennial subject was the life, or lack of it, in their eyes. A naked woman’s glance toward her viewer became the core of the two paintings that established his reputation as the father of modernism: Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia. The scandal of the fact that the nudes in both paintings were probably also high-class courtesans, living off the generosity of their loyal sex partners (like Odette in Proust’s novel who rises to the highest ranks of Parisian society) announced Manet’s talent and deviously witty stance toward both the society and the artistic establishment of his day. The way he depicted the amoral world he saw in his high-class milieu looked transgressive to the arbiters of art. In reality, his paintings were good-humored satire on how modern life, as he experienced it, had little to do with the work being shown at the Salon exhibitions in Paris.

He was a truth teller with the heart of an outsider, and this outraged his contemporaries because in painting, nudity was expected to live within predictable narrative boundaries. In 1869, for example, Loudet’s interpretation of Cephalus and  Procris hung on the walls of the exhibition, an accomplished painting within the acceptable guard rails: an interpretation of the Greek myth in which one could pretty much plead to having painted bare breasts under duress because it was required by a noble Greek myth. This workaround enabled what could have passed for soft-core porn to get into the Salon and be received with respect. Fragonard had painted a more prurient vision of the story, a typically amazing bit of Rococco painting from him, and it was a subject many painters reprised.

Procris hung on the walls of the exhibition, an accomplished painting within the acceptable guard rails: an interpretation of the Greek myth in which one could pretty much plead to having painted bare breasts under duress because it was required by a noble Greek myth. This workaround enabled what could have passed for soft-core porn to get into the Salon and be received with respect. Fragonard had painted a more prurient vision of the story, a typically amazing bit of Rococco painting from him, and it was a subject many painters reprised.

The nudity of Loudet’s painting was justified by the story-telling. Manet gently mocked the whole process of smuggling nakedness into the exhibition under the guise of noble or spiritual tropes. While structuring his images in ways similar to the presentation of unclothed women in the past, he showed his figures in contemporary settings, women being naked for no reason other than to be naked, or to make a living that way. If Olympia had been embraced by the critics, it might have become the first unapologetic centerfold of its time, but actually it’s not even as tamely erotic as Fragonard’s lush, seductively-lit work. It’s realistic, not titillating, and thus it’s a funny contrast to all the other heroic presentations of breasts. Manet was shamed for his wit. Like his contemporary, Flaubert, he created a kind of realism that at first served to epater le bourgeoisie until he began to use it to express some of the most fleeting and elusive moments in human life. Moments in life live on his canvases the way they do later in movies or in candid, “street” photography. His snapshots were precursors of Gary Winogrand and Vivian Maier. This was his magic: to trap life in flight, and watch it seem to move in place, a butterfly in a jar. Early on, as a result of his notoriety, he became friends with other kindred rebels, Baudelaire and Mallarme as well as the Impressionists, a group whose work he studied but whose esthetic he never completely adopted.

He didn’t really fit anywhere, except in the company of Degas, whose work advanced alongside his. Manet lurked around the edges of what was happening, studying and using some of it. He couldn’t give himself over completely to the Impressionist preoccupation with the pleasures of atmospheric color. It wasn’t the world he saw around him. It’s been said his favorite color was black, and his vision of life was far more sober and conflicted than the visions of Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Sisley and Morisot. He was driven by his fascination with individual human personalities and the need to convey them through portraits that seem like a freeze-frame within a narrative, qualities he admired in the paintings of those he emulated, Velasquez and even Hals. Yet he was gifted in his use of color in the late work and his ability to create scenes that seem to move before your eyes. He wasn’t alone in this: Renoir’s boating party has an even more kinetic energy. But Manet brought gravity to his scenes; his groupings are more subtle and more psychologically complicated. The quietly funny element that runs through his work can’t be found in most of what was being painted around him. His talent put him in league with the Impressionists for several years with a mastery of color and light that equals their work, on their terms, as much as he resisted it. It didn’t completely satisfy him.

What seems most mobile and alive in his images are the eyes of women. Many times he painted a woman’s face isolated in space, without context, classic portraiture. But his ambition was to situate them as the pictorial foundation of small gatherings, to build scenes that invest mundane, commonplace narratives—as ordinary and casual as Bruegel’s scenes of peasant life or Chardin’s and Vermeer’s genre paintings—with ambiguities. They beckon to you and resist interpretation, hinting at a story without divulging exactly what’s happening.

If you spend time studying the arc of his career, you see how hard he had to struggle for every achievement, finding his own individual way. In the final paintings, his skill frees him to make a commonplace scene flicker with momentary life. What recedes is the posed look of the early work that made him famous. His carefully structured pictures seem like candid snapshots. He painted wet paint into wet paint, alla prima, and in many cases it looks as if he dashes off a painting in a single sitting with ease, yet there’s often some area that seems unfinished or unrealized, refusing to surrender itself to the eye as easily as the rest. He labored on his technique and his paintings. Even in his virtuosity you see him wrestling with the medium until the last few years when he got bolder and bolder; there’s rarely the sense of unconscious perfection you detect in Sargent’s bravura marks or in the uncanny way the earlier Degas seems to conjure the life around him with flawless assurance and ease. Degas was usually polished, until he began to experiment with pastel at the turn of the century. With both painters, the older they got, the more original and interesting their work became.

Most of Manet’s surfaces have a hard-won quality. Part of this is that, like Degas and Cezanne, he was always grappling with the world’s weight and volume, no matter how the images seem to flatten things out onto the painting’s surface. It would be nice, right now, to hear what Clement Greenberg would have to say about them, how he would try to either dismiss them or see the slight flattening of an image as a harbinger of what he thought was the essence of the art form, which would ignore what made Manet who he was. With the core Impressionists, the world seems to materialize as a condensation of ambient light. Yet Manet and Degas situate the human spirit in a physical world that resists: one has only to look at the late pastels of Degas to see the yoga-like contortions of the human figure struggling against the resistance of its own anatomy, his dancers seemingly cousins of Michelangelo’s slaves.

From the start, in Manet, the glory of the human body looks vulnerable, the warm target of a cold world. The naked woman absurdly lounging with her formally clothed male companions in Luncheon on the Grass glances languidly and happily toward the viewer, but one wants to give her a shawl, protect her against her own audacity. In Olympia, our escort into sex work reclines on her feather bed, taunting you with her control of male desire, clothed only in choker, bracelet and mules with a bouquet of flowers arriving from a client. Yet even indoors, her pale skin seems bleached under a kind of tabloid flash of light. She doesn’t have the warm glow of Titian’s Venus—the ironic model for Manet’s painting. She presents the hard, fit body of a professional whose coarse exhibitionism is her defense against a predatory world. She stays one step ahead of it by becoming its collaborator, by extracting a living from that world by doing little more than what we see her doing at leisure: reclining on a bed. The irony of her occupation is compounded by the title: could this be Mount Olympus with a giant goddess leaning back onto its slope, her votary bringing flowers? So, there you go, critics: it’s Greek myth after all! And Manet pulls the servant up close to the foreground, giving her a supporting role. This gracious servant comes across as easier to like than our meretricious goddess. He never forgot the horror he felt in his teens as a naval cadet who watched African slaves being sold in Rio de Janeiro. Slavery and serfdom were being abolished in France, America and Russia contemporaneously with Manet’s earlier work, so in a way his painting did have a quietly mythic resonance. The balance of power here was shifting as a black servant moves up to the foreground, nearly sharing the spotlight with her employer: all of this contemporary resonance was built into the image, yet all of it looked unsuitable to the critics.

Yet the visual heart of the painting is the look in the courtesan’s eyes: fully alive, intelligent, detached, taunting, amused, shrewd. Manet admires, even loves her. She’s a woman who knows how to control and put the male gaze to work for her, including the eyes of the man painting her, like Raphael’s Fornarina, seemingly ready to mount the painter’s lap in the Ingres painting, fully in control of her partner.

In their era, Manet, Degas and Cezanne, working at the periphery of Impressionism, produced work more challenging than the rest, as wonderful as as the others were. These three seem the most complex, most enduring and the closest to achieving what Cezanne meant when he said he wanted to make art solid and durable enough for the museums. Cezanne was the most original of the three, and the least conflicted in his aims and his style, but all three struggled to unify opposing impulses in their work: the natural look of atmospheric light balanced with a concern for the opaque, dense physicality of the world, its weight and heft and mystery. Degas and Manet kept negotiating a middle ground between the new sense of modernity emerging around them and their love of the classic, traditional and enduring qualities of traditional painting. The young Degas immersed himself in the Italian Renaissance, and Manet found himself enthralled by Velasquez and Goya and spent years working under their influence.

Degas and Manet are brothers in the darker, sedate quality of their earlier work. Both also shifted to pastel as they freed themselves from their darker antecedents and they the medium offered them an almost expressionist/fauvist freedom. At first glance, Degas is easier to love, the natural and classic beauty of his early and middle periods and the intensity of his color in the late pastels. But in Manet’s incremental progress, you can feel his long struggle for recognition and understanding, his refusal to belong with his contemporaries, his complex dependence on the women in his life, as friends, partners and subjects for his work. There’s something deeply contemporary in Manet’s unique achievement, his almost misfit role, like Van Gogh’s. But Manet was even less suited than Van Gogh to a vision of history that sees the progress of art from centuries of tradition into the wild experimentation of the 20th century. Van Gogh seems a more forthright step from the past into a future he helped make possible. Manet fits neatly into neither the past nor the future: he’s like most or maybe all painters now. He is one of us. There’s no history to fit into unless you create an arbitrary school with rules for painting, but then it’s just a group choosing ways to paint, a la carte, from the way it’s been done before, and that’s a path individuals have to carve out on their own: find a way to paint that justifies itself without pretending to be a movement forward since there’s no way to go forward now. Manet was perfect for this predicament because he didn’t want to go anywhere, least of all toward something better, as he witnessed French society gyrate from republic to monarchy to republic and commune, turning in its gyre, going in circles. Mostly he distrusted the notion of progress in art. He just wanted to paint in a way that was true to what he loved about painting and what he saw in the life around him, simply to convey the quiddity of daily life and human individuality. His mission was to make a painting where the people in it came alive, nothing more. And that drew him into new ways of painting almost against his will.

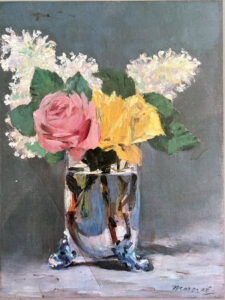

Lilacs in a Glass

on canvas, (10⅔6 × 8¼”)

I’ve always loved Manet for his small, late floral still life paintings, which could be argued are his greatest achievement in technique even though in subject and size one thinks they could serve as the definitive paradigm of “minor paintings.” Minor paintings or not, they are major achievements, swiftly executed and devoted to color, but only the color that’s actually there, only the color visible to the sober eye. Only recently did I go back and survey how he got to them, and what I discovered was not only an incredibly gifted portraitist but also a painter who took years to discover a way to paint, improving and expanding his skill until freedom and discipline merged near the end—a painter who flourished only during his last decade.

2

There’s an arc that runs from Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia through his entire career ending with Barmaid at the Folie Bergere, a sequence of paintings that represent what he probably considered his major work, scenes of social life, human figures unaware that they are being watched, doing ordinary things. Manet’s core notion of a painting that mattered was one that showed you people doing things that don’t matter. None of these paintings resonate in spirit with Renoir’s boating party, where all the young hipsters, lit by sunlight and alcohol, seem to epitomize youth and beauty and pleasure. It’s as high-spirited and joyful as a television commercial, a representation of peak experience, good-looking youth partying. Manet’s characters don’t inhabit this world. Like Chekhov’s, they occupy a world of thought that seems both disconnected from and bound to the interior world of the other people but in a disjointed and intermittent way. In the scandalous paintings that announced him, he assembled a small number of people to create a moment that ironically comments on Parisian mores. A prostitute gloats about her success. A couple flaneurs share lunch with a naked female companion looking so out of place you want to laugh, except for the air of mystery hinting at Giorgione. The message is clear and simple: in Paris, anything goes, for better or worse. But when Manet returns to scenes of daily life as the years pass, he leaves behind the irony, the implications of upper-class moral hypocrisy. He shows life without the implicit meta-commentary implied by his merger of tradition with what was shockingly au courant. His eye and heart become far more empathetic, and he builds on his skills to keep pace with this shift.

If you track how his approach changes from 1868 until his death fifteen years later, you see how his images grow in life and spontaneity and his palette expands to express a greater range of emotion and experience. His work early on seems devoted to showing the life of the ruling classes, the affluent and privileged, without the scandal. His figures often pose formally in a narrow range of tones. When he depicts his friend and fellow painter Berthe Morisot in The Balcony, she and her companions could pass for an illustration for The Ambassadors or The Golden Bowl. These members of the leisure class could be watching a parade or simply enjoying early spring warmth in the fresh air, dressed formally, properly, only vaguely aware of one another. In a more commanding painting, Lunch in the Studio, Manet shows a confident and well-fed 16-year-old in a boater, likely Manet’s own illegitimate son, looking off into the distance after a meal, a servant awaiting instructions behind him. Manet captures the pride and indifference in the boy’s face, but also an absorbed thoughtfulness. It’s all in the eyes. It’s a genre scene but also a great portrait. It’s also one of his few paintings that pivot around a male figure.

If you track how his approach changes from 1868 until his death fifteen years later, you see how his images grow in life and spontaneity and his palette expands to express a greater range of emotion and experience. His work early on seems devoted to showing the life of the ruling classes, the affluent and privileged, without the scandal. His figures often pose formally in a narrow range of tones. When he depicts his friend and fellow painter Berthe Morisot in The Balcony, she and her companions could pass for an illustration for The Ambassadors or The Golden Bowl. These members of the leisure class could be watching a parade or simply enjoying early spring warmth in the fresh air, dressed formally, properly, only vaguely aware of one another. In a more commanding painting, Lunch in the Studio, Manet shows a confident and well-fed 16-year-old in a boater, likely Manet’s own illegitimate son, looking off into the distance after a meal, a servant awaiting instructions behind him. Manet captures the pride and indifference in the boy’s face, but also an absorbed thoughtfulness. It’s all in the eyes. It’s a genre scene but also a great portrait. It’s also one of his few paintings that pivot around a male figure.

A few years later, similar work moves outdoors where the couple—though the shapes are composed with even more care—don’t seem posed and every inch of the canvas is illuminated now with outdoor light. Now Manet channels the influence of Impressionism into his visions of inconsequential occasions that feel universal, intimate but part of a larger, recognizable world. Considered as a body of work, these paintings show you the terms of middle-class happiness: you can get this far with the pleasures of bourgeois life, and no further. This is as lucky as it gets, people, even if something’s missing.

show you the terms of middle-class happiness: you can get this far with the pleasures of bourgeois life, and no further. This is as lucky as it gets, people, even if something’s missing.

In The Railway, Victorine Meurent, his model for Olympia and other paintings—an accomplished painter herself whose work was exhibited at the Salon—serves as the nanny looking up from her book while her ward, a young girl in a white pinafore dress looks toward the train passing below the wrought iron railings that offer a compositional grid. It’s a perfectly structured image both surprisingly arranged but expertly balanced, a cloud of steam from the locomotive erasing much of the background to set off the figures and push them forward. Meurent’s glance toward the viewer, one imagines, lasts only seconds before she goes back to her book, while the girl will soon wander around looking for something to play with. The scene brims with life, as do all of his paintings at this point. Nothing important is actually happening here: nothing more than the perfection and beauty of what would otherwise be a trivial moment in a routine day. The scene revolves around a pair of thoughtful, attentive eyes, the nanny looking up gently to meet our admiring gaze. A little sleeping puppy cuddles in her lap.

The painting reflects Manet’s affection for what he sees. One could almost imagine him asking solicitously, “How’s the book?” and Victorine’s modest “Ok. It’ll do. How’s the painting?” Manet chuckles. And then the train is gone, the girl moves away and both of his subjects forget he’s there. The life in Meurent’s face is the focal point: you can see her warm personality, quite different from her hauteur in Olympia. From that same face, now soft and sisterly, this moment assembles itself, as poetic and elusive as a Japanese haiku. The color scheme is strict, white and blue and black, and the skin tones, a balance of opposites in the two figures, but everything feels alive, about to shift, like sunlight swaying through leaf shadows.

In the Conservatory shows figures that could have been posing for the work, but still it seems as if we’re eavesdropping on an intimate moment between husband and wife or a pair of lovers meeting secretly. It’s as if the man or the woman has just shared some observation and both are dwelling on what was said. It’s as if the man or the woman has just shared some observation and both are dwelling on what was said. She looks off into the distance, and he looks down toward her, but maybe past her, thinking, weighing what he’s heard. Again, everything appears proper to upper-middle class life, exemplifying its privilege but also its confines. The row of dowels in the back of the bench, marching across the bottom of the picture, echo the wrought iron in The Railway, like prison bars keeping the little girl at a distance from the unseen steam engine. These lives are played out within guard rails, and Manet recognizes the beauty those limitations make possible. Clearly he was ambivalent about those boundaries, though it isn’t clear that he was ever unfaithful to his wife; his disease could have been the outcome of an encounter before his marriage, and his most intense relationships with female friends and sitters appear to have been Platonic.

In the Conservatory shows figures that could have been posing for the work, but still it seems as if we’re eavesdropping on an intimate moment between husband and wife or a pair of lovers meeting secretly. It’s as if the man or the woman has just shared some observation and both are dwelling on what was said. It’s as if the man or the woman has just shared some observation and both are dwelling on what was said. She looks off into the distance, and he looks down toward her, but maybe past her, thinking, weighing what he’s heard. Again, everything appears proper to upper-middle class life, exemplifying its privilege but also its confines. The row of dowels in the back of the bench, marching across the bottom of the picture, echo the wrought iron in The Railway, like prison bars keeping the little girl at a distance from the unseen steam engine. These lives are played out within guard rails, and Manet recognizes the beauty those limitations make possible. Clearly he was ambivalent about those boundaries, though it isn’t clear that he was ever unfaithful to his wife; his disease could have been the outcome of an encounter before his marriage, and his most intense relationships with female friends and sitters appear to have been Platonic.

In these same years Manet finishes a series of paintings that fully assimilate Impressionism, without abandoning his fixation on the solidity and centrality of the human figure. In Boating, Argenteuil, and Banks of the Seine at Argenteuil he demonstrates that he can achieve the outdoor radiance of his peers and yet still offer human figures that don’t seem merely another surface to reflect the light around them: they have heft, gravity and a tentative, expectant individual inner life, even seen from a distance. In Argenteuil, the picture is built almost like a puzzle, patches of different, distinct color to indicate sky, river, boat, trees. He shows you something photographers shun: the brilliance of direct midday sun, but with nothing washed out, nothing lost in shadow. The green goes here, the Naples yellow there, the magenta stripes beside the plum-and-blue stripes, a haze of pink clouds under blue skies, every shape fitted into its proper place as rigorously as a flat Japanese print, and yet everything snaps into focus and shimmers with movement, looking natural, casual, alive, and real.

solidity and centrality of the human figure. In Boating, Argenteuil, and Banks of the Seine at Argenteuil he demonstrates that he can achieve the outdoor radiance of his peers and yet still offer human figures that don’t seem merely another surface to reflect the light around them: they have heft, gravity and a tentative, expectant individual inner life, even seen from a distance. In Argenteuil, the picture is built almost like a puzzle, patches of different, distinct color to indicate sky, river, boat, trees. He shows you something photographers shun: the brilliance of direct midday sun, but with nothing washed out, nothing lost in shadow. The green goes here, the Naples yellow there, the magenta stripes beside the plum-and-blue stripes, a haze of pink clouds under blue skies, every shape fitted into its proper place as rigorously as a flat Japanese print, and yet everything snaps into focus and shimmers with movement, looking natural, casual, alive, and real.

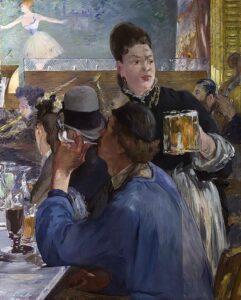

Three other paintings in particular bring his looser and more confident brushwork indoors, into his home territory, in paintings that feel like screen grabs of a film: Corner of a Café-Concert, At Père Lathuille’s and  The Café-Concert. In the first, a robust waitress stands next to a small orchestra, holding a couple mugs of beer, posed behind a man in a blue smock who smokes a pipe, while in the background it appears a ballerina has wandered out of a Degas painting into this one, but she’s actually a singer on stage. Everything is organized around the waitress’s distracted, wary expression: something puzzles or concerns her for a second, but only long enough to size it up before delivering her beers. In At Père Lathuille’s, a young man with wispy sideburns and mustache is making his move, hitting on the woman at this table, while she sits upright, her head above his, looking down at his eyes, amused, skeptical, but listening. All of this comes through with only the tiniest application of paint to indicate what little of her eyelashes and lips are visible from behind, where Manet situates the viewer. On the other hand, this fellow could actually be listening to whatever

The Café-Concert. In the first, a robust waitress stands next to a small orchestra, holding a couple mugs of beer, posed behind a man in a blue smock who smokes a pipe, while in the background it appears a ballerina has wandered out of a Degas painting into this one, but she’s actually a singer on stage. Everything is organized around the waitress’s distracted, wary expression: something puzzles or concerns her for a second, but only long enough to size it up before delivering her beers. In At Père Lathuille’s, a young man with wispy sideburns and mustache is making his move, hitting on the woman at this table, while she sits upright, her head above his, looking down at his eyes, amused, skeptical, but listening. All of this comes through with only the tiniest application of paint to indicate what little of her eyelashes and lips are visible from behind, where Manet situates the viewer. On the other hand, this fellow could actually be listening to whatever she’s telling him. In either case she’s in control of his eagerness. The waiter in the background—with only the brief flecks of paint Manet indicates his slightly amused expression—glances toward the viewer as if to say with his eyes: “Get a load of this guy.” The image is so mobile, so alive, the painting has the feel of a Disney animation. Again and again, Manet’s paintings are like a single frame from a stop-action sequence, more than a decade before the first motion picture was offered to a paying public.

she’s telling him. In either case she’s in control of his eagerness. The waiter in the background—with only the brief flecks of paint Manet indicates his slightly amused expression—glances toward the viewer as if to say with his eyes: “Get a load of this guy.” The image is so mobile, so alive, the painting has the feel of a Disney animation. Again and again, Manet’s paintings are like a single frame from a stop-action sequence, more than a decade before the first motion picture was offered to a paying public.

The Café-Concert brings a psychological complexity of its everydayness, its quiet pathos and the implicit humor of the scene. A top-hatted, aristocratic older man sits at the bar, steadying his cane with one hand, using its grip to prop up his other wrist. It’s as if he’s maintaining a buffer, a bit of quarantine between himself and the surface under his beer. Meanwhile, on another planet two feet away, a younger but haggard woman, a shopgirl maybe, is smoking her cigarette, also nursing a beer, but looking down toward the  bar, thinking of something, the note of loss in her eyes, or at least a wistful longing to be somewhere or someone else. The pathos of her dispirited face isn’t tragic, or depressing, but touching, especially juxtaposed in a comic way against the posture and look of the Duc de Guermantes there next to her, slumming, maybe listening to the singer far behind him, maybe taking a break from his wife back home in the Faubourg St. Germaine. Between that distant singer and these two drinkers in the foreground, a waitress has decided to join in and finish the beer someone left on the table—or it could be a customer just enjoying a seventh-inning stretch. The two drinkers are hardly aware of each other, coming from opposite ends of the wealth-and-privilege spectrum, but they are bound together by the beer and the distant look in their eyes. What could be further from the epic narratives and propriety of the paintings celebrated at the Salon? And yet how contemporary and immediate all of this work feels now, understated, intimate, forgiving, without spectacle or motive other than the enjoyment of seeing people being ordinary people, muddling through a day.

bar, thinking of something, the note of loss in her eyes, or at least a wistful longing to be somewhere or someone else. The pathos of her dispirited face isn’t tragic, or depressing, but touching, especially juxtaposed in a comic way against the posture and look of the Duc de Guermantes there next to her, slumming, maybe listening to the singer far behind him, maybe taking a break from his wife back home in the Faubourg St. Germaine. Between that distant singer and these two drinkers in the foreground, a waitress has decided to join in and finish the beer someone left on the table—or it could be a customer just enjoying a seventh-inning stretch. The two drinkers are hardly aware of each other, coming from opposite ends of the wealth-and-privilege spectrum, but they are bound together by the beer and the distant look in their eyes. What could be further from the epic narratives and propriety of the paintings celebrated at the Salon? And yet how contemporary and immediate all of this work feels now, understated, intimate, forgiving, without spectacle or motive other than the enjoyment of seeing people being ordinary people, muddling through a day.

You can draw half a dozen narratives from this painting, all built around the look in the eyes of these two figures. Manet likes them both, but it’s the woman who gets his affection, his compassion, his empathy. Gone is the glory of Impressionism. Manet is back in black. But he has brought with him that dancing flame of the fleeting moment, tempis fugit, where time and life fuse into what’s gone as soon as it appears. The shopgirl here seems to have an encore in Plum Brandy, dressed in pink, still smoking as she shelters another kind of drink, just as lost in thought. Both of those paintings are like a reply, an homage, to In a Café by Degas. Manet and Degas were the Brian Wilson and Paul McCartney of their time, or the Picasso and Matisse, or the Gauguin and Van Gogh: mutual fans and competitors and spiritual collaborators. (The drawings Degas made of Manet are loving and masterful, testimony to a deep artistic partnership.)

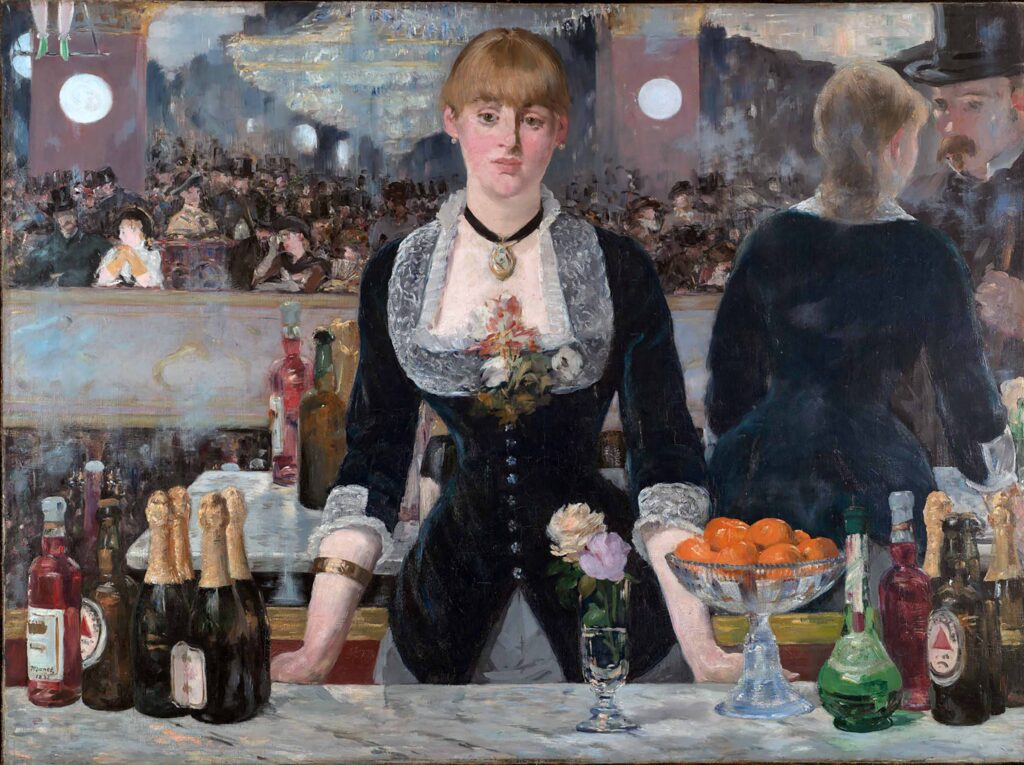

In his final triumph, where everything came together for Manet, just before he died, Barmaid at the Folie Bergere, he tackled his most visually complicated scene, with dozens of people in the background and more than a dozen objects in the foreground, yet he simplified it in a composition that is utterly stable and balanced, except for the oddity of the reflection of the barmaid’s back in the mirror off to the right. That visually illogical element gives the realism of the scene a dreamlike touch, as if she has projected a ghostly hologram of what’s going on in her mind as she looks at you, after having asked what you’d like to drink. In that case, she’s either imagining it’s you a foot in front of her, where she can get a better look, or she’s dreaming of someone she served earlier. Again, Manet has returned to his roots: the formal, elegant black of evening wear dominates the canvas. But his touches of color everywhere stand out all the more now and are the way he imports his assimilation of Impressionism into a painting: the grenadine of the bottles, the brilliant orange of the mandarin oranges in a large compote, the browns of the Bass beer, but most of all the flushed alluring pink of the barmaid’s rouged cheeks. It’s a lovely face, hovering over the white lace of her bodice, and again the choker, with a pendant now, and the bracelet (echoes of Olympia, but now she is fully clothed and has a corsage to hide even her cleavage.) We are at the follies, a cross between a burlesque revue and a variety show, as strip clubs used to be, but in her reserve and poise, the boundaries are all in place now. She’s a perfect combination of readiness and modesty, friendliness and formality, a barmaid but an exemplar of genteel manners and propriety, with a smile just starting to play on her lips, though her eyes aren’t quite there for you, at least not yet—maybe she’s dreaming of that other fellow you see in the mirror to the right. It can’t be you in the mirror, because clearly that guy is a foot or two away from her face, and you are back far enough to see everything on the bar. She’s present and not really present, at your service but inaccessible, playing her role but dreaming of other things, as caged as the little girl in The Railway, or a prostitute in her job for that matter, but also as free as that little girl as well, free to ignore you and go home to her book or her lover or her child after the show is over.

the browns of the Bass beer, but most of all the flushed alluring pink of the barmaid’s rouged cheeks. It’s a lovely face, hovering over the white lace of her bodice, and again the choker, with a pendant now, and the bracelet (echoes of Olympia, but now she is fully clothed and has a corsage to hide even her cleavage.) We are at the follies, a cross between a burlesque revue and a variety show, as strip clubs used to be, but in her reserve and poise, the boundaries are all in place now. She’s a perfect combination of readiness and modesty, friendliness and formality, a barmaid but an exemplar of genteel manners and propriety, with a smile just starting to play on her lips, though her eyes aren’t quite there for you, at least not yet—maybe she’s dreaming of that other fellow you see in the mirror to the right. It can’t be you in the mirror, because clearly that guy is a foot or two away from her face, and you are back far enough to see everything on the bar. She’s present and not really present, at your service but inaccessible, playing her role but dreaming of other things, as caged as the little girl in The Railway, or a prostitute in her job for that matter, but also as free as that little girl as well, free to ignore you and go home to her book or her lover or her child after the show is over.

She’ll soon turn away and go back to her life. But nothing is certain, anything is possible here, the narrative isn’t clear. A lowly barmaid represents something like perfection within the insignificant confines of her role, the glow of her face, the unpredictable nature of what’s going on in her life and in her innermost thoughts. All that spectacle going on in the background, with the feet of the trapeze artist barely visible in the upper corner, but Manet ignores it and offers us this pretty, obscure caterer off in her quiet corner. Again and again, in this mature work, you get from Manet what you get from Chekhov: the humor and pathos of ordinary life, the anti-heroic and absurd juxtapositions of mundane activities, the beauty of unique human beings a bit lost in their lives, hearts aching slightly, but not really miserable, or even deeply unhappy. Just wistful, a lump starting in the throat, but laughing. This complex, deeply felt narrative core of Manet’s work distinguished him from most of the modernists around him except for Degas, who was his soul mate. Gauguin’s narratives, his island mysteries, were of a different order.

3

The technical mastery Manet achieved in these last years is exemplified and becomes most visible in the less ambitious work, especially in the floral still lifes that all seem to be inspired by the little bud vase with two flowers he placed in front of his barmaid. There are a half dozen of these paintings that look perfectly executed, intuitive, quick, not effortless, but assured, once and done, like the tiny, almost Japanese ink drawings he sent off in flirting letters to a woman thirty years younger whose portrait he’d painted at least seven times, Isabelle Lemonnier,  never getting an answer from her in the mail. At the top of one letter, he dashes off a perfect cat with a few strokes of ink and in another, he conveys her face as skillfully as a caricaturist, but without cartoonish distortion. His facility as a draftsman, equal to Matisse and Picasso, was with a brush rather than a line.

never getting an answer from her in the mail. At the top of one letter, he dashes off a perfect cat with a few strokes of ink and in another, he conveys her face as skillfully as a caricaturist, but without cartoonish distortion. His facility as a draftsman, equal to Matisse and Picasso, was with a brush rather than a line.

Roses, lilacs, clematis, pansies, violets: he tackles them all, using cloudy areas with dashes of color to indicate individual flowers for the lilacs that emerge from clouds of white with green-ish blue interiors, and slashes of paint for rose petals, the cut glass vases and little jars with what look like marbles for feet. These are illuminated mostly with daylight, like Chardin’s later still lifes with light-toned backgrounds, Manet’s backdrops echo the sky-blue reflections of light in the glass, or just neutral colors in middle values, all of it a glimpse of domestic order and contentment, so close to Chardin, even though Manet was suffering at the end, in pain for a decade, finally struggling with the loss of his leg to gangrene.

His quick portraits have the same brevity and immense energy. His Woman Reading could be a manic pixie dream girl transported back from our time, cute and pink-cheeked, glancing up from her newspaper or book, it’s hard to tell. Her eyes are a marvel: intelligent, amused, even skeptical, and very individualized, a distinctly recognizable face, all executed with minimal detail and spontaneous brushwork. Manet takes this ability even further in three paintings that push almost beyond realism.

executed with minimal detail and spontaneous brushwork. Manet takes this ability even further in three paintings that push almost beyond realism.

The power of this loose, quick work gave him the confidence to push beyond what he’d been doing into a stylistic region almost Fauvist or expressionist in the way he gave rein to the paint itself and to unbridled impulses in his mark-making

In Café-Concert Singer the paint gives us a glimpse of the woman, holding flowers, standing on stage, but the brushwork almost takes over, almost becomes the subject of the work itself, akin to Van Gogh’s thick marks, but less regular, less rhythmic, more chaotic, jazzier. In a late pastel/gouache, a portrait of one of his closest friends and frequent models, Mery Laurent in a Veil, an upper-class courtesan who hosted a salon that included some of the most notable minds of the era: Mallarmé, Zola, Proust, Whistler, and Manet. Her face in this pastel is nearly obscured and becomes an extension of the blue sky behind her, her hat and  stole, or scarf, seem like one continuous object, with a streak of facial shadow that links them in color, the blues from the hat continuing in the cavity where her eye disappears, the red echoed in her lips. Everything is almost arbitrary, the marks wildly inconclusive, almost frenetic.

stole, or scarf, seem like one continuous object, with a streak of facial shadow that links them in color, the blues from the hat continuing in the cavity where her eye disappears, the red echoed in her lips. Everything is almost arbitrary, the marks wildly inconclusive, almost frenetic.

And in his portrait of George Moore, owned by the Metropolitan, he transcends all of the limits he’s put on himself in the past. It’s as if he’s writing in oil—the pastel is almost indistinguishable from oil paint on canvas—and it’s nearly the automatic writing of the surrealists. The long marks of pastel on canvas feel like calligraphy. He carves his way to a vision of what he can’t see until it’s revealed by his hand, letting the stub of pastel do whatever it’s doing in some way he can’t anticipate. The eyes are little scribbles and one iris seems covered by a pink curve that seems to represent nothing one would actually see in a face: nobody’s eyes have those pink lashes. But somehow it works, like an intensification of the red hair and beard, even though the other eye is represented by a serifed apostrophe of gray for the iris and areas of pale yellow and blue. Raw canvas shows through everywhere. The color of the canvas itself becomes part of the face’s tonality. The hair and beard are almost violently applied with smears of orange-brown pastel. The scarf erupting between his coat’s lapels looks like a spiderweb. Nothing is presented in any way one would expect it to be, and of course the critics mocked it, the way they greeted so much of his work. From the Met’s website:

This pastel, executed in one sitting, depicts the Irish critic and novelist George Moore. He used it as the frontispiece for his book Modern Painting (1893), noting that as “a fresh-complexioned, fair-haired young man, the type most suitable to Manet’s palette, [the artist] at once asked [him] to sit.” Critics ridiculed this work when it was exhibited in 1880, calling it “Le Noyé repêché” (the drowned man fished out of the water).

It’s hard to believe it wasn’t painted in oil, but it’s pastel on canvas, and the shift to this medium had to be one the factors that freed Manet up to find himself doing things he probably never would have anticipated. It’s a magnificent portrait, an elongated face like an updated El Greco, full of the sitter’s Irish impertinence, as animated as any of the scenes he’d painted in the past, as if he’d captured Moore in mid-sentence.

Manet’s work could be painted and exhibited now and would fit into any number of exhibitions of contemporary representational painting. Paradoxically, he achieved timelessness by trying to simply paint his age more perceptively than anyone around him. In these last portraits and in the little floral still lifes, one feels that, at the doorstep of death and in chronic pain, Manet was just getting started. It’s exactly how he felt. His last surviving letter ends with the sentence: “I’m getting better and better.” Wonderfully, and tragically, he was.

Comments are currently closed.