My slow path to painting

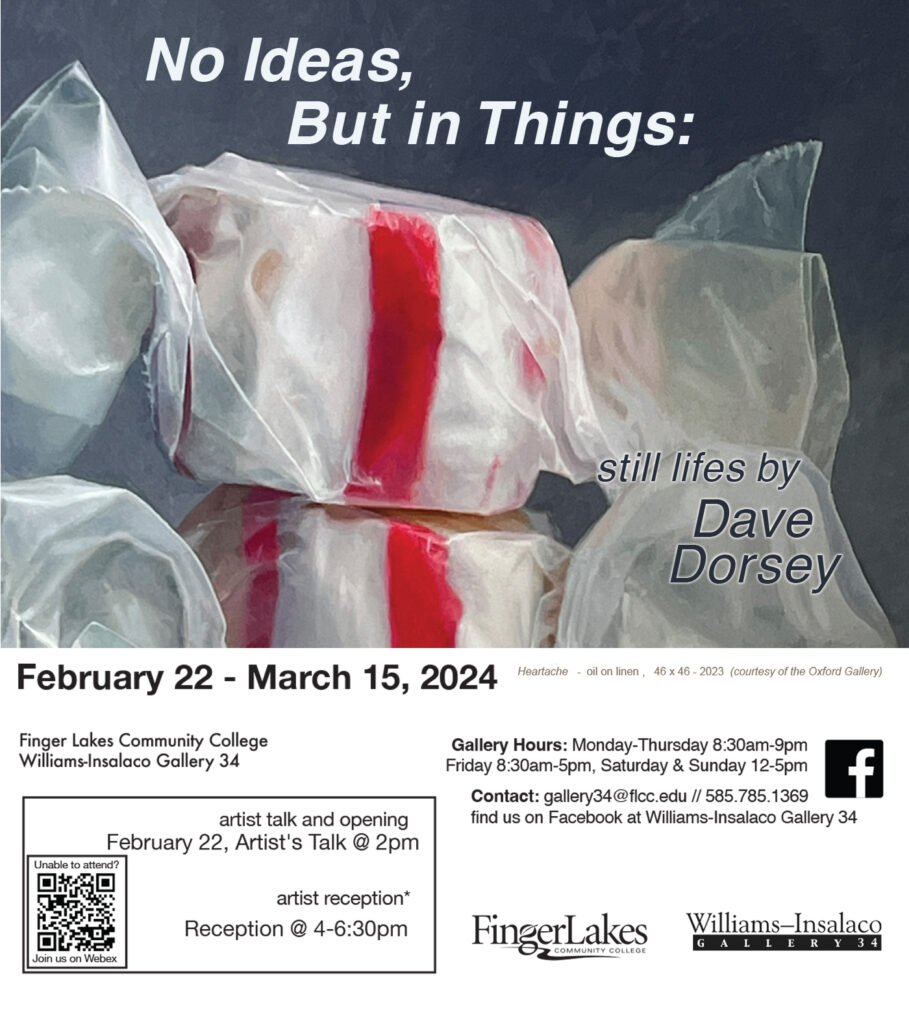

I’m going to deliver about eighteen paintings to the Williams-Insalaco Gallery today for a solo show opening next week: No Ideas But In Things. It’s the motto coined by William Carlos Williams for the Imagist poets a century ago. The exhibition is a survey of work I’ve done over the past decade. I’m giving a talk mostly for the art students at FLCC, describing my slow progress to where I am now as a painter. I’m going to open with my wisdom about being a painter, reduced down to five words: Don’t quit your day job. This was a crucial choice for me, to make money in other ways and make paintings in the time that remained. (I still have the vestige of a non-art day job, though I work full days as a painter.) This choice delayed my ability to become a professional artist, but also gave me the freedom to experiment and simply learn to absorb what I loved in the work of others and learn from it at my own pace. I think highly ambitious artists who are determined to go to Yale or Pratt and then start exhibiting in New York City and selling for high prices within a few years of having gotten an MFA are at risk of losing touch with what drives them to be an artist. Anyone who succeeds commercially in short order will, of necessity, be under pressure to adapt to the demands of collectors and critics. A painter can easily lose touch with what prompted him or her to make art in the first place.

I didn’t go to art school for a couple reasons. One, I didn’t feel at home with much of what was going on in the art world in the 1960s when I was in my teens and in love with the work of the early modernists: Van Gogh, Gauguin, Chagall, Braque, Klee, Matisse, Burchfield, and others. As art progressed into the mid-20th century it became less and less appealing to me. I felt like a late-comer. I thought that I had to somehow fit into my historical moment, so effectively this opportunity had come and gone before I was born. But I also began to wonder how the practice of painting could progress at all beyond the work of the abstract expressionists and color field painters. It seemed as if painting had run its course. A cluster of other, weirder ways of being an artist had sprung up in a desperate attempt to keep the idea of the avant garde alive. Performance art, happenings, minimalism, conceptual art, installations and so on. Everyone was struggling to do something new when the idea of newness had exhausted itself. It all seemed contrived and arbitrary. It seemed painting had nowhere else to go. This didn’t keep me from painting. But I assumed I would need to do it simply because I enjoyed it without any hope of finding a way of belonging to an art scene that had moved beyond me. So I kept painting without attempting to make a living from it. I avoided a degree in art, even though in my thirties I studied at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute and the Memorial Art Gallery.

I got a master’s degree in English, became a reporter, got jobs in newspapers and then with a small advertising agency in Rochester. I began freelance magazine writing and eventually authored a couple books. But meanwhile several things happened. I saw two exhibitions at Munson-Williams-Proctor in Utica, one a survey of contemporary realists, and the other a solo show of work by Raymond Han, an obscure still life painter who had an attitude toward a career in art much like mine. He had a little studio in Cooperstown, never exhibited his work, and sold to collectors who heard about his still lifes via word of mouth. (I think he had to have been living on an inheritance.) At one point, a curator from the Guggenheim, who had a second residence in Cooperstown, discovered Han’s work and began to promote it. The result was a major museum solo exhibition devoted solely to his paintings. It was a bit of a Cinderella moment for him, and it led to at least one show at Forum Gallery in Manhattan, as well as establishing his work on the radar of collectors even after his death.

All of the work I saw in those two exhibitions changed the way I viewed painting. It was possible to do serious representational work and be considered a “relevant” contemporary painter, whatever the word “relevant” means these days. Shortly after that I read an essay by art critic Arthur Danto where he asserted that art history had ended—confirming what I’d felt in my teens—there was nowhere for it to go in the sense of making progress toward some new school that broke new theoretical ground to serve as the Next Big Thing. But he proposed this as a kind of liberation: artists now could individually do anything they chose, with their own individual philosophy of art. Suddenly, any sort of painting was interesting as a way of uniquely learning from the history of art and finding an idiosyncratic way to make it personally vital. Painters were finally free to do anything, regardless of what anyone else was doing. There was no herd to follow anymore. The only rule was to go forth and push some paint around in whatever way you found most fruitful.

The Guggenheim curator wrote a little appreciation in the printed hand out for the Han exhibition and mentioned Chardin as a predecessor. (Han disagreed with that comparison and cited the French neoclassicists as more influential.) So when my wife and I moved back to Rochester with our son and daughter, I went into the Rush Rhees library at the University of Rochester, where I’d gotten my undergraduate degree, and I found a couple big books full of Chardin’s paintings. I remember the young student librarian with a puzzled smile looking at me, “Why the interest in Chardin?” I shrugged and smiled. It was too hard to explain. At roughly the same time, I came across two books that actually taught me what I needed to know about contemporary representational painting: The Art of the Real and Realists at Work. There were some great still life painters in those books: William Bailey and Janet Fish. All of the featured painters were just as eye opening. These books were like a couple semesters in art school for me: they taught me many things, both about what could be done and how it was done. There was detailed descriptions of work processes at a practical level. Each of the painters described how they worked. They were my professors, more or less. In studying the images of the paintings but also in reading the interviews devoted to each of the artists featured in the books, I learned to refine the way I painted.

Realists at Work had an interview with Ralph Goings, the photorealist famous for his paintings of small town diners. It’s wonderful as a real life account of how someone finds his way in art by fits and starts. I learned that he spent fifteen years teaching art in high school. He began as an abstractionist but his enthusiasm waned, and he quit painting for a year. Then he started doing things he found ridiculous but interesting just out of curiosity: just copying photographs, at first in a sort of experimental mode, then trying to find interesting shots in magazines to copy, and then finally he realized he could use his own photographs as sources for paintings. He said all the abstractionists around him mocked what he was doing, so he began doing it to spite them, as a provocation. He learned that others were projecting and tracing images from slides—the equivalent back then of using a digital projector and throwing an image up from a computer onto a canvas, which is how I usually work now. I learned from Goings to project an image and do a detailed line drawing of shapes and forms, then paint by looking at the original photograph displayed on a computer screen. The original Photorealists would work from a photographic print or a slide projected off to the side of the canvas. I’ve never understood how anyone could paint directly into a projected image: the color of the projection would distort the color of the paint.

Again, Goings continued to be mocked for doing something so mundane and unheroic and so dependent on technology. But he loved doing it. Eventually he became a star of the Photorealist movement. The interview with him shows that belonging to some school or movement wasn’t what drove him: he found his way in an isolated, idiosyncratic way and then realized others were doing the same thing. (This is probably a gross simplification of how it worked; he had to have been aware of what some of his contemporaries were doing. He learned about projecting an image from them and so on.) But what makes his work interesting isn’t that it’s photorealistic but that it conveys the feel of being in a diner. Diners are like an American, alcohol-free version of an English pub, where the help calls you “honey” and you can get something delicious for a low price and nobody is pretentious. It’s a humble everyday realm, full of humanity and something universal and wonderfully welcoming. You feel this even in his paintings of diners without a single human being in view. What was most delightful in the interview with Goings was how, even in an era where everyone was doing anything imaginable and calling it art, other painters were mocking Photorealism and telling him “you can’t do that!” Goings replied, “Oh yeah, just watch me.” That’s been the cry of modernists since the beginning with the Impressionists. But what gives his work such heart isn’t that it was sort of countercultural within his own ambit as a painter—it doesn’t look like that now—but that he loved the subject and the process. It was personally gratifying. And that comes through in the finished work.

Within a few years I was focused on still life painting and by 1991, the Oxford Gallery, under its previous ownership, had agreed to represent me. But my writing career caught up with me at exactly the same time and my book proposal to follow a Xerox Corporation sales team around for a year—to live with them and take notes like a documentary film maker and write about their lives—created a stir with New York publishers. My agent auctioned off the proposal, and I got a large advance from Random House. I rented an apartment in Cleveland, where I spent the work week, driving home to my wife and kids on the weekends. My painting came to a halt for those months, but once the book research was done, I dug back in. The success I had with the book created enough momentum to keep me focused primarily on writing through the 90s. I published a novel; I wrote for magazines. But after the dot.com collapse and the attack on the World Trade Center, my magazine work dried up, and I couldn’t find a way to write about subjects that engaged me. I felt about writing the way Ralph Goings ended up feeling about abstraction. I had a problem because I wasn’t making much of a living as a writer or a painter. My wife, a school teacher, was paying most of the bills. Through my book editor, I met Peter Georgescu, a retired business leader who needed a ghostwriter to help him pull together a book about his life and what he’d learned running Young & Rubicam, a multinational marketing agency in New York City, which he had been heading up as CEO and Chairman. I’ve been working with him ever since, partnering with him in writing books and helping him draft posts for Forbes. I’m still on retainer with him.

I bid goodbye to the Oxford Gallery with that flood of work as a writer, but around 2008, I approached it again, and Jim Hall, the new owner, agreed to include me in shows and a few years later I signed an agreement with him and he’s been my only dealer until last year.

My writing work with Peter left me far more time to paint. Within five years, I had decided to devote most of my time to painting, while still allocating enough hours to do my writing, which I enjoyed. It was an unusual, maybe unique way to juggle the need for money and job satisfaction. The Internet had emerged, and as a result it became possible to apply to juried exhibitions around the country—something that would have been much more difficult a couple decades earlier. I began entering shows in 2007 and continued to do that for the past 15 years. By 2008 I had refined my still life paintings to the point where I had a painting accepted into the Memorial Art Gallery’s Finger Lakes Exhibition and won an award both there and at another show organized by Xavier University. Every year I entered as many as a dozen shows and got into anywhere from three to eight or even nine. Some years I was in only two or three shows. This process of painting and entering exhibitions became my core vocation, and writing became the way I paid the bills. Meanwhile I started writing a blog about visual art, without ever monetizing it, which may or may not eventually lead to some kind of book about painting.

I’m still writing for Peter, with a regular, small check—three of them per year—to keep me on retainer for my help with his blog posts at Forbes. I’m at an age where people are fully retired, but I still haven’t quit my day job. It works perfectly. I’m able to get my writing done efficiently enough to leave me a full work day at the easel, six or seven days a week. I consider myself a moderately successful painter, acquainted with many other artists, some more widely known. I’ve been painting for half a century and only now am I on the cusp of what I would consider genuine success—the possibility of reaching collectors in the largest U.S. cities. I’m being represented at the L.A. Art Show by Arcadia Contemporary as I write this, one of the most respected galleries in Manhattan, located in SoHo, and if I can continue to paint energetically and purposefully throughout the coming year I may find I have a substantially larger income from painting than ever before. It all depends on what sells in Los Angeles. If things don’t work out, I’ll continue doing what I’ve been doing for decades, the way I’ve been doing it. I’ve exhibited all over the U.S. and twice in Europe. My work is in many private collections and two universities own my paintings. This is hardly a major success, given the wildly lucrative careers some artists have now in the art world where buying has become so speculative and aligned with other investment strategies for the super-wealthy. But I look back to painters like Ralph Goings and Raymond Han, and many of my friends here in the area, like the two artists the Williams-Insalaco Gallery is named after, as models of a deeper kind of success: the achievement of idiosyncratic excellence.

The turning point for me was in the 80s when I woke up to the fact that I could be a painter in a way that was contemporary, a way that would allow me to belong in my own era by simply doing what I most loved to do. I learned that everything and anything belongs to our era as long as it works and people want to look at it. I learned the proper response when somebody says, “that isn’t art. You can’t do that anymore.” Oh yeah? Just watch me.

Comments are currently closed.